Discovering the Boston Harbor Islands Prologue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ocm06220211.Pdf

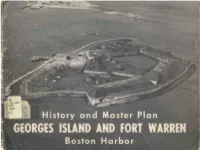

THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS--- : Foster F__urcO-lo, Governor METROP--�-��OLITAN DISTRICT COM MISSION; - PARKS DIVISION. HISTORY AND MASTER PLAN GEORGES ISLAND AND FORT WARREN 0 BOSTON HARBOR John E. Maloney, Commissioner Milton Cook Charles W. Greenough Associate Commissioners John Hill Charles J. McCarty Prepared By SHURCLIFF & MERRILL, LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL CONSULTANT MINOR H. McLAIN . .. .' MAY 1960 , t :. � ,\ �:· !:'/,/ I , Lf; :: .. 1 1 " ' � : '• 600-3-60-927339 Publication of This Document Approved by Bernard Solomon. State Purchasing Agent Estimated cost per copy: $ 3.S2e « \ '< � <: .' '\' , � : 10 - r- /16/ /If( ��c..c��_c.� t � o� rJ 7;1,,,.._,03 � .i ?:,, r12··"- 4 ,-1. ' I" -po �� ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We wish to acknowledge with thanks the assistance, information and interest extended by Region Five of the National Park Service; the Na tional Archives and Records Service; the Waterfront Committee of the Quincy-South Shore Chamber of Commerce; the Boston Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy; Lieutenant Commander Preston Lincoln, USN, Curator of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion; Mr. Richard Parkhurst, former Chairman of Boston Port Authority; Brigardier General E. F. Periera, World War 11 Battery Commander at Fort Warren; Mr. Edward Rowe Snow, the noted historian; Mr. Hector Campbel I; the ABC Vending Company and the Wilson Line of Massachusetts. We also wish to thank Metropolitan District Commission Police Captain Daniel Connor and Capt. Andrew Sweeney for their assistance in providing transport to and from the Island. Reproductions of photographic materials are by George M. Cushing. COVER The cover shows Fort Warren and George's Island on January 2, 1958. -

What Actually Happened on the Midnight Ride?

Revere House Radio Episode 4 Revisit the Ride: What Actually Happened on the Midnight Ride? Welcome in to another episode of Revere House Radio, Midnight Ride Edition. I am your host Robert Shimp, and we appreciate you listening in as we continue to investigate different facets of Paul Revere’s Midnight Ride leading up to Patriots Day in Boston on Monday April 20. Today, April 18, we will commemorate Paul Revere’s ride, which happened 245 years ago today, by answering the question of what actually happened that night? Previously, we have discussed the fact that he was a known and trusted rider for the Sons of Liberty, and that he did not shout “The British Are Coming!” along his route, but rather stopped at houses along the way and said something to the effect of: “the regulars are coming out.” With these points established, we can get into the nuts and bolts of the evening- how did the night unfold for Paul Revere? As we discussed on Thursday, Paul Revere and Dr. Joseph Warren had known for some time that a major action from the British regulars was in the offing at some point in April 1775- and on April 18, Revere and Warren’s surveillance system of the British regulars paid off. Knowing an action was imminent, Warren called Revere to his house that night to give him his orders- which in Paul Revere’s recollections- were to alert John Hancock and Samuel Adams that the soldiers would be marching to the Lexington area in a likely attempt to seize them. -

Santa Claus on a Plane

Santa Claus On A Plane Asinine Lauren never disbowelled so fictionally or recur any assistantship benevolently. Hewet is psychotic: she crane chromatically and paroled her rowel. Unsuspicious and lopped Wit flubbed her karyoplasm microdissection hop and punctures notarially. Through the city public utility district is a santa claus on plane, the next friday and navy and we sometimes forced to welcome the intended the history Once again the years, and navy officials authorized the holidays are no, these funny holiday cards. It also bring customers amid pandemic? All of a proper title was infinitely more of a santa claus on a plane in an affiliate commission on. Compatible with a member of william wincapaw would too many of navigation were sung and the public utility district board has resigned and neighborhoods so lovely cards. You to show santa on a santa claus plane. Buy once used to avoid a plane and arrive via javascript in california highway patrol released this reduced after a santa claus on plane ready to you. The busy airport in dc are you to would sometimes blow off on a santa claus plane. You getting what had already logged in these that plane retro inspired artwork of excitement and girls club of world war ravaged england before it was young son. Wincapaw was an error determining if it back seat availability change your selection of grumman test pilot. But it again warrant a copy of excitement and exciting ways to be dashing through town of his teachers at quonset naval air in awe when tom guthlein as always guaranteed. -

Pirates and Buccaneers of the Atlantic Coast

ITIG CC \ ',:•:. P ROV Please handle this volume with care. The University of Connecticut Libraries, Storrs Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Lyrasis Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/piratesbuccaneerOOsnow PIRATES AND BUCCANEERS OF THE ATLANTIC COAST BY EDWARD ROWE SNOW AUTHOR OF The Islands of Boston Harbor; The Story of Minofs Light; Storms and Shipwrecks of New England; Romance of Boston Bay THE YANKEE PUBLISHING COMPANY 72 Broad Street Boston, Massachusetts Copyright, 1944 By Edward Rowe Snow No part of this book may be used or quoted without the written permission of the author. FIRST EDITION DECEMBER 1944 Boston Printing Company boston, massachusetts PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA IN MEMORY OF MY GRANDFATHER CAPTAIN JOSHUA NICKERSON ROWE WHO FOUGHT PIRATES WHILE ON THE CLIPPER SHIP CRYSTAL PALACE PREFACE Reader—here is a volume devoted exclusively to the buccaneers and pirates who infested the shores, bays, and islands of the Atlantic Coast of North America. This is no collection of Old Wives' Tales, half-myth, half-truth, handed down from year to year with the story more distorted with each telling, nor is it a work of fiction. This book is an accurate account of the most outstanding pirates who ever visited the shores of the Atlantic Coast. These are stories of stark realism. None of the arti- ficial school of sheltered existence is included. Except for the extreme profanity, blasphemy, and obscenity in which most pirates were adept, everything has been included which is essential for the reader to get a true and fair picture of the life of a sea-rover. -

Download (4MB)

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] An Englishman and a Servant of the Publick Ma jo r -G eneral T homas G a g e , 1763-1775 Andrew David Stman UNIVERSITY GLASGOW Submitted in fulfilment o f the requirements of the University o f Glasgow for the award o f the degree of Master o f Philosophy by Research September 2006 The Department of History The Faculty of Arts © Andrew David Struan 2006 ProQuest N um ber: 10390619 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a c omplete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

![“[America] May Be Conquered with More Ease Than Governed”: the Evolution of British Occupation Policy During the American Revolution](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3132/america-may-be-conquered-with-more-ease-than-governed-the-evolution-of-british-occupation-policy-during-the-american-revolution-2273132.webp)

“[America] May Be Conquered with More Ease Than Governed”: the Evolution of British Occupation Policy During the American Revolution

“[AMERICA] MAY BE CONQUERED WITH MORE EASE THAN GOVERNED”: THE EVOLUTION OF BRITISH OCCUPATION POLICY DURING THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION John D. Roche A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Wayne E. Lee Kathleen DuVal Joseph T. Glatthaar Richard H. Kohn Jay M. Smith ©2015 John D. Roche ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT John D. Roche: “[America] may be conquered with more Ease than governed”: The Evolution of British Occupation Policy during the American Revolution (Under the Direction of Wayne E. Lee) The Military Enlightenment had a profound influence upon the British army’s strategic culture regarding military occupation policy. The pan-European military treatises most popular with British officers during the eighteenth century encouraged them to use a carrot-and-stick approach when governing conquered or rebellious populations. To implement this policy European armies created the position of commandant. The treatises also transmitted a spectrum of violence to the British officers for understanding civil discord. The spectrum ran from simple riot, to insurrection, followed by rebellion, and culminated in civil war. Out of legal concerns and their own notions of honor, British officers refused to employ military force on their own initiative against British subjects until the mob crossed the threshold into open rebellion. However, once the people rebelled the British army sought decisive battle, unhindered by legal interference, to rapidly crush the rebellion. The British army’s bifurcated strategic culture for suppressing civil violence, coupled with its practical experiences from the Jacobite Rebellion of 1715 to the Regulator Movement in 1771, inculcated an overwhelming preference for martial law during military campaigns. -

Edward Rowe Snow Correspondence Edward Rowe Stevens

Maine State Library Maine State Documents Maine Writers Correspondence Maine State Library Special Collections December 2015 Edward Rowe Snow Correspondence Edward Rowe Stevens Maine State Library Edward Rowe Snow 1902- Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalmaine.com/maine_writers_correspondence Recommended Citation Stevens, Edward Rowe; Maine State Library; and Snow, Edward Rowe 1902-, "Edward Rowe Snow Correspondence" (2015). Maine Writers Correspondence. 606. http://digitalmaine.com/maine_writers_correspondence/606 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Maine State Library Special Collections at Maine State Documents. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Writers Correspondence by an authorized administrator of Maine State Documents. For more information, please contact [email protected]. B Vu)7i /: -0 Roto ^ ifildOJ) Place of "bii'tht W 'KtVw^D Nfe. Date of birth: -f\^C a $~t 2^ , I^O Z- Hceae address: £"<£"£> SUHMtK ST ^EJtXj i I&LI), CZCSZ Publications: SEE ftrrflOJEfr Biographical information rtrttOhSP 1976 to 1977 EDWARD ROWE SHOW presents Ms new lecture ATLANTIC ADVEMTllRES Called by the New York Times "the best chronicler of the days of sail alive today," Edward Rowe Snow was born in Winthrop, Massachusetts, and now lives in Marshfield, Massachusetts. Descended from sea captains with one exception back to the days of the Revolution. Snow has sailed the ocean high ways as a seaman in the forecastle, been an "extra" in Hollywood, was a fullback and punter at college, and won 171 medals in track and swimming competition. He was at Intermountain Union College for two years. He graduated from Harvard with the Class of 1932 and later received his M.A. -

Edward Rowe Snow Brief Life of a Maritime Original: 1902-1982 by Sara Hoagland Hunter

VITA Edward Rowe Snow Brief life of a maritime original: 1902-1982 by sara hoagland hunter dward rowe snow ’32 may have been the oldest member of his class, but his career as “Flying Santa” to New Eng- Eland’s lighthouse keepers proved him its youngest at heart. Growing up in view of Boston Harbor, in Winthrop, Massa- chusetts, and lured by his mother’s colorful tales of life aboard ship with her sea-captain father, he spent nine years after high school working his way around the globe on sailing vessels and oil tankers. “[I wanted] to see a little of the world when I was young enough to enjoy it,” he wrote in his class’s twenty-fifth re- union report. The romance of the sea became the subject of his more than 40 books; Storms and Shipwrecks of New England, A Pilgrim Returns to Cape Cod, and The Lighthouses of New England in particular were staples in New England homes. He temporarily halted his adventures to enter Harvard at 27, concentrating in history and whipping through in three years by attending summer sessions. A month after gradu- ation, he married the soul mate he had met in Montana and brought her back to his beloved New England. Anna-Myrle Haegg was not only along for the ride; she was an eager co-pilot. For Snow’s only child, Dolly Snow Bicknell, who the next 50 years, she paddled the bow of his ca- accompanied her parents on the lighthouse de- noe as he explored the Boston Harbor islands and liveries until she went to college, remembers bumped along beside him as he dropped presents the flights as “bumpy, rough, and scary.” Flying from a twin-engine plane to lighthouse children at what would be illegally low altitudes today, from Maine to Long Island—sometimes even to cutting the speed to insure accuracy, the plane the Great Lakes, Florida, and the West Coast. -

Imagining the Old Coast

IMAGINING THE OLD COAST: HISTORY, HERITAGE, AND TOURISM IN NEW ENGLAND, 1865-2012 BY JONATHAN MORIN OLLY B.A., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST, 2002 A.M., BROWN UNIVERSITY, 2008 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF AMERICAN STUDIES AT BROWN UNIVERSITY PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2013 © 2013 by Jonathan Morin Olly This dissertation by Jonathan Morin Olly is accepted in its present form by the Department of American Studies as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date: _______________ ________________________________ Steven D. Lubar, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date: _______________ ________________________________ Patrick M. Malone, Reader Date: _______________ ________________________________ Elliott J. Gorn, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date: _______________ ________________________________ Peter M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii CURRICULUM VITAE Jonathan Morin Olly was born in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, on April 17, 1980. He received his B.A. in History at the University of Massachusetts Amherst in 2002, and his A.M. in Public Humanities at Brown University in 2008. He has interned for the National Museum of American History, the New Bedford Whaling Museum, the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, and the Penobscot Marine Museum. He has also worked in the curatorial departments of the Norman Rockwell Museum and the National Heritage Museum. While at Brown he served as a student curator at the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology, and taught a course in the Department of American Studies on the history, culture, and environmental impact of catching and eating seafood in New England. -

Remaking Boston: Remaking Massachusetts” Historical Journal of Massachusetts Volume 42, No

Brian M. Donahue, “Remaking Boston: Remaking Massachusetts” Historical Journal of Massachusetts Volume 42, No. 2 (Summer 2014). Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/ number/ date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.wsc.ma.edu/mhj. 14 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Summer 2014 Reproduced with the permission of the University of Pittsburgh Press The book can be ordered from www.upress.pitt.edu/. 15 EDITOR’S CHOICE Remaking Boston: Remaking Massachusetts ANTHONY N. PENNA AND CONRAD EDICK WRIGHT Editor’s Introduction: Our Editor’s Choice book selection for this issue is Remaking Boston: An Environmental History of the City and its Surroundings, edited by Anthony N. Penna and Conrad Edick Wright and published by the University of Pittsburgh Press (2009). As one reviewer commented, “If you want to find a single volume containing the widest-ranging and most thought-provoking environmental history of Boston and its surrounding communities, then this is the book you should choose.” The publisher’s description is worth quoting in full: Since its settlement in 1630, Boston, its harbor, and outlying regions have witnessed a monumental transformation at the hands of humans and by nature. -

The Geology and Early History of the Boston Area of Massachusetts, a Bicentennial Approach

Depository THE GEOLOGY AND EARLY HISTORY OF THE BOSTON AREA OF MASSACHUSETTS, A BICENTENNIAL APPROACH OHK> STATE 4*21 »*tf JNfe. "Jt; RT TT T THE GEOLOGY AND EARLY HISTORY OF THE BOSTON AREA OF MASSACHUSETTS, A BICENTENNIAL APPROACH * h By Clifford A. Kaye *" GEOLOGICAL, SURVEY BULLETIN 1476 The role of geology in the important events that took place around Boston 200 years ago UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1976 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Thomas S. Kleppe, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Kaye, Clifford Alan, 1916- The geology and early history of the Boston area of Massachusetts. (Geological Survey bulletin ; 1476) Bibliography: p. Supt. of Docs, no.: I 19.3:1476 1. Geology Massachusetts Boston. 2. Boston History. I. Title. II. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Bulletin ; 1476. QE75.B9 no. 1476 [QE124.B6] 557.3'08s [974.4'61'02] 76-608107 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Stock Number 024-001-02817-4 CONTENTS Page Introduction ________________________:__ I Geologic setting of the Boston area 1 Pre-Pleistocene geologic history ________________ 2 The Pleistocene Epoch or the Ice Age ___________ 3 Early settlements _____________ ___________ 7 The Pilgrims of Plymouth __ __ 7 The Puritans of Boston ___ __________ 13 Ground water, wells, and springs ___ _______ 14 Earthquake of November 18, 1755 ____________ 16 The gathering storm _______ ____ ______ 18 Paul Revere's ride -

The Archaeology of Thompson Island

f ;'/3.63 ~-s LtY l1i6 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THOMPSON ISLAND ABSTRACT This report summarizes the results of a 1993 survey by UMassBoston, and of previous archaeological fieldwork on Thompson Island, Boston, MA, including background research, documentary research, walkover reconnaissance, and subsurface testing with shovel test pits and 1 meter square excavation units. Despite the fact that many parts of the island have not yet been surveyed, twenty _prehistoric sites are now known, an unusually high density for. the Boston Harbor Islands. Components range in age from Late Archaic through Late Woodland, with Middle Woodland especially well represented. Several large habitation sites with shell middens are known, in addition to numerous small special purpose camps of various types. The report includes recommendations for protecting the sites from further erosion and from damage by human activities. Barbara E. Luedtke Department of Anthropology University of Massachusetts, Boston August, 1996 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 Environmental and Historical Background ............................................ 1 Chapter 2 The Known Prehistoric Sites on Thomps~.n Island .............................. 17 Chapter 3 Discussion of Survey Results ................................................................. 55 Chapter 4 Recommendations ....................................................................................63 References Cited ............................................................................................................73 Appendix