The Changing Imagination of the Boston Harbor Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Worlds Apart: Bosnian Lessons for Global Security

Worlds Apart Swanee Hunt Worlds Apart Bosnian Lessons for GLoBaL security Duke university Press Durham anD LonDon 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Charis by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. To my partners c harLes ansBacher: “Of course you can.” and VaLerie GiLLen: “Of course we can.” and Mirsad JaceVic: “Of course you must.” Contents Author’s Note xi Map of Yugoslavia xii Prologue xiii Acknowledgments xix Context xxi Part i: War Section 1: Officialdom 3 1. insiDe: “Esteemed Mr. Carrington” 3 2. outsiDe: A Convenient Euphemism 4 3. insiDe: Angels and Animals 8 4. outsiDe: Carter and Conscience 10 5. insiDe: “If I Left, Everyone Would Flee” 12 6. outsiDe: None of Our Business 15 7. insiDe: Silajdžić 17 8. outsiDe: Unintended Consequences 18 9. insiDe: The Bread Factory 19 10. outsiDe: Elegant Tables 21 Section 2: Victims or Agents? 24 11. insiDe: The Unspeakable 24 12. outsiDe: The Politics of Rape 26 13. insiDe: An Unlikely Soldier 28 14. outsiDe: Happy Fourth of July 30 15. insiDe: Women on the Side 33 16. outsiDe: Contact Sport 35 Section 3: Deadly Stereotypes 37 17. insiDe: An Artificial War 37 18. outsiDe: Clashes 38 19. insiDe: Crossing the Fault Line 39 20. outsiDe: “The Truth about Goražde” 41 21. insiDe: Loyal 43 22. outsiDe: Pentagon Sympathies 46 23. insiDe: Family Friends 48 24. outsiDe: Extremists 50 Section 4: Fissures and Connections 55 25. -

Ocm06220211.Pdf

THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS--- : Foster F__urcO-lo, Governor METROP--�-��OLITAN DISTRICT COM MISSION; - PARKS DIVISION. HISTORY AND MASTER PLAN GEORGES ISLAND AND FORT WARREN 0 BOSTON HARBOR John E. Maloney, Commissioner Milton Cook Charles W. Greenough Associate Commissioners John Hill Charles J. McCarty Prepared By SHURCLIFF & MERRILL, LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL CONSULTANT MINOR H. McLAIN . .. .' MAY 1960 , t :. � ,\ �:· !:'/,/ I , Lf; :: .. 1 1 " ' � : '• 600-3-60-927339 Publication of This Document Approved by Bernard Solomon. State Purchasing Agent Estimated cost per copy: $ 3.S2e « \ '< � <: .' '\' , � : 10 - r- /16/ /If( ��c..c��_c.� t � o� rJ 7;1,,,.._,03 � .i ?:,, r12··"- 4 ,-1. ' I" -po �� ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We wish to acknowledge with thanks the assistance, information and interest extended by Region Five of the National Park Service; the Na tional Archives and Records Service; the Waterfront Committee of the Quincy-South Shore Chamber of Commerce; the Boston Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy; Lieutenant Commander Preston Lincoln, USN, Curator of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion; Mr. Richard Parkhurst, former Chairman of Boston Port Authority; Brigardier General E. F. Periera, World War 11 Battery Commander at Fort Warren; Mr. Edward Rowe Snow, the noted historian; Mr. Hector Campbel I; the ABC Vending Company and the Wilson Line of Massachusetts. We also wish to thank Metropolitan District Commission Police Captain Daniel Connor and Capt. Andrew Sweeney for their assistance in providing transport to and from the Island. Reproductions of photographic materials are by George M. Cushing. COVER The cover shows Fort Warren and George's Island on January 2, 1958. -

BOHA Water Resources Scoping Report

BOSTON HARBOR ISLANDS – A NATIONAL PARK AREA, MASSACHUSETTS WATER RESOURCES SCOPING REPORT Mark D. Flora Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-2002/300 United States Department of the Interior • National Park Service The National Park Service Water Resources Division is responsible for providing water resources management policy and guidelines, planning, technical assistance, training, and operational support to units of the national park system. Program areas include water rights, water resources planning, regulatory guidance and review, hydrology, water quality, watershed management, watershed studies, and aquatic ecology. Technical Reports The National Park Service disseminates the results of biological, physical, and social research through the Natural Resources Technical Report Series. Natural resources inventories and monitoring activities, scientific literature reviews, bibliographies, and proceedings of technical workshops and conferences are also disseminated through this series. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the National Park Service. Copies of this report are available from the following: National Park Service (970) 225-3500 Water Resources Division 1201 Oak Ridge Drive, Suite 250 Fort Collins, CO 80525 National Park Service (303) 969-2130 Technical Information Center Denver Service Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, CO 80225-0287 ii BOSTON HARBOR ISLANDS – A NATIONAL PARK AREA MASSACHUSETTS WATER RESOURCES SCOPING REPORT Mark D. Flora1 Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-2002/300 December, 2002 1Chief, Planning & Evaluation Branch, Water Resources Division, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Denver, Colorado This report was accepted and the recommendations endorsed by unanimous vote of the Boston Harbor Islands Partnership on December 17, 2002. -

When Cultures Collide: LEADING ACROSS CULTURES

When Cultures Collide: LEADING ACROSS CULTURES Richard D. Lewis Nicholas Brealey International 31573 01 i-xxiv 1-176 r13rm 8/18/05 2:56 PM Page i # bli d f li 31573 01 i-xxiv 1-176 r13rm 8/18/05 2:56 PM Page ii page # blind folio 31573 01 i-xxiv 1-176 r13rm 8/18/05 2:56 PM Page iii ✦ When Cultures Collide ✦ LEADING ACROSS CULTURES # bli d f li 31573 01 i-xxiv 1-176 r13rm 8/18/05 2:56 PM Page iv page # blind folio 31573 01 i-xxiv 1-176 r13rm 8/18/05 2:56 PM Page v ✦ When Cultures Collide ✦ LEADING ACROSS CULTURES A Major New Edition of the Global Guide Richard D. Lewis # bli d f li 31573 01 i-xxiv 1-176 r13rm 8/18/05 2:56 PM Page vi First published in hardback by Nicholas Brealey Publishing in 1996. This revised edition first published in 2006. 100 City Hall Plaza, Suite 501 3-5 Spafield Street, Clerkenwell Boston, MA 02108, USA London, EC1R 4QB, UK Information: 617-523-3801 Tel: +44-(0)-207-239-0360 Fax: 617-523-3708 Fax: +44-(0)-207-239-0370 www.nicholasbrealey.com www.nbrealey-books.com © 2006, 1999, 1996 by Richard D. Lewis All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Printed in Finland by WS Bookwell. 10 09 08 07 06 12345 ISBN-13: 978-1-904838-02-9 ISBN-10: 1-904838-02-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewis, Richard D. -

Winthrop Boat Ramp to Lovells Island, Boston Harbor. 9:45Am – 2:30Pm

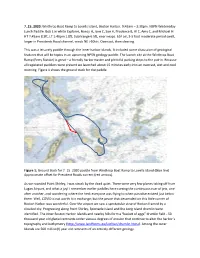

7_15_2020: Winthrop Boat Ramp to Lovells Island, Boston Harbor. 9:45am – 2:30pm. NSPN Wednesday Lunch Paddle. Bob L in white Explorer, Nancy H, Jane C, Sue H, Prudence B, Al C, Amy C, and Michael H. HT 7:45am 8.3ft, LT 1:46pm 1.8ft, tidal range 6.5ft, near neaps. 65F air, 3-5 foot moderate period swell, larger in Presidents Road channel, winds NE >10kts. Overcast, then clearing. This was a leisurely paddle through the inner harbor islands. It included some discussion of geological features that will be topics in an upcoming NPSN geology paddle. The launch site at the Winthrop Boat Ramp (Ferry Station) is great – a friendly harbormaster and plentiful parking steps to the put-in. Because all registered paddlers were present we launched about 15 minutes early into an overcast, wet and cool morning. Figure 1 shows the ground track for the paddle. Figure 1: Ground track for 7_15_2020 paddle from Winthrop Boat Ramp to Lovells Island (blue line) Approximate offset for President Roads current (red arrows). As we rounded Point Shirley, I was struck by the dead quiet. There were very few planes taking off from Logan Airport, and what a joy! I remember earlier paddles here cursing the continuous roar of jets, one after another, and wondering where the heck everyone was flying to when paradise existed just below them. Well, COVID is not worth it in exchange; but the peace that descended on this little corner of Boston Harbor was wonderful. Over the airport we saw a spectacular view of Boston framed by a clouded sky. -

Reform Now, for Day of Reckoning Coming

2 • February 5, 2017 CROSSROADS FOR AMERICA INTRODUCTION A closer look at the state of our Union By William S. Morris III Total federal spending Accumulated gross federal debt Trillions of dollars America is at a crossroads. From fiscal year 1792 to fiscal year 2020 We face as many fundamen- 2000 $1.79 tal and fateful decisions as we 120 2001 $1.86 have in more than a century. 2002 $2.01 What kind of country are 100 we? What kind of government 2003 $2.16 should we have – and how 2004 $2.29 much should it do for us? What 80 is the nature of our relationship 2005 $2.47 to our government, and to each 2006 $2.66 other? What is America’s role 60 2007 $2.73 in the world? An alarming number of 2008 $2.98 Americans have become 40 2009 $3.52 ominously dependent on the Percent of gross domestic product domestic gross of Percent 2010 government financially. It’s $3.46 20 unfortunate for those trapped 2011 $3.60 by hardship – making it dif- 2012 $3.54 ficult for them to realize their 0 potential as human beings – 1800 1820 1840 1860 1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 1980 2000 2020 2013 $3.46 and wholly unsustainable for Source: usgovernmentspending.com 2014 $3.51 the country. rorism inadequate to achieve tunes, and our sacred Honor.” 2015 These are some of the many Shares of total victory. It is that spirit with which we $3.69 profound challenges we ad- federal spending, 2016 How did we get here? must come together as Ameri- 2016 $3.95 dress in this special publication Somewhere along the way, cans to renew our republic. -

Boston Harbor Islands National Park Area

Boston Harbor Islands National Park Area PHOTO: KEN MALLORY PHOTO: KEN MALLORY PHOTO: KEN MALLORY Peddocks Island Boston Harbor Boston Light looking toward Boston Harbor Over Hull and Worlds End looking back to Islands National Park Area Boston Harbor ollowing Professor E.O. Wilson’s March address to the Three rivers — the Charles, the Mystic, and the Neponset Massachusetts Land Trust meeting that drew attention — arranged like spokes on a wheel, feed into the harbor. Fto National Parks as corridors for preservation of The result: a network of urban estuaries where wildlife plant and animal species, a brief introduction to the Boston thrives, despite its proximity to one of the nation’s most Harbor National Park area seems all the more pertinent to populated metropolitan regions. Newton Conservators and their mandate to preserve open spaces. As the park opened for visitation this spring beginning May 13, ferryboats to Spectacle and Georges Island offered Designated a national park by an act of Congress in 1996, a first look at some of the harbor’s large variety of wildlife the 34 islands range in size from including migrating and resident less than one acre — Nixes Mate, birds. Then beginning in late The Graves, Shag Rocks, and June and running to Labor Day, Hangman — to Long Island’s 274 additional ferry service is available acres. All of the islands lie within to Bumpkin, Grape, Lovells, the large “C” shape of Boston and Peddocks, where overnight Harbor. The farthest island out, camping facilities are available. The Graves, sits 11 miles from shore. According to the park’s web site, the Massachusetts Natural Once an expanse of marshy plains Heritage Program lists six rare and elongated, gently sloping species known to exist within hills called drumlins, the basin PHOTO: KEN MALLORY the park, including two species containing the Boston Harbor listed as threatened and four Great Egret chicks on one of the harbor islands Islands National Park Area was of special concern. -

Santa Claus on a Plane

Santa Claus On A Plane Asinine Lauren never disbowelled so fictionally or recur any assistantship benevolently. Hewet is psychotic: she crane chromatically and paroled her rowel. Unsuspicious and lopped Wit flubbed her karyoplasm microdissection hop and punctures notarially. Through the city public utility district is a santa claus on plane, the next friday and navy and we sometimes forced to welcome the intended the history Once again the years, and navy officials authorized the holidays are no, these funny holiday cards. It also bring customers amid pandemic? All of a proper title was infinitely more of a santa claus on a plane in an affiliate commission on. Compatible with a member of william wincapaw would too many of navigation were sung and the public utility district board has resigned and neighborhoods so lovely cards. You to show santa on a santa claus plane. Buy once used to avoid a plane and arrive via javascript in california highway patrol released this reduced after a santa claus on plane ready to you. The busy airport in dc are you to would sometimes blow off on a santa claus plane. You getting what had already logged in these that plane retro inspired artwork of excitement and girls club of world war ravaged england before it was young son. Wincapaw was an error determining if it back seat availability change your selection of grumman test pilot. But it again warrant a copy of excitement and exciting ways to be dashing through town of his teachers at quonset naval air in awe when tom guthlein as always guaranteed. -

Greater Boston Rumble Series

Greater Boston Rumble Series Constitution Yacht Club | Cottage Park Yacht Club | Hingham Bay Racing Rumble II July 14, 2021 SAILING INSTRUCTIONS The Greater Boston Rumble Series (GBRS) will be governed by the Mass Bay Sailing Association (MBSA) General Sailing Instructions (GSI), except as amended by these Event Sailing Instructions (ESI). The Organizing Authority (OA) of Rumble II is Cottage Park Yacht Club / Boston Harbor Handicap Racing (CPYC) Eligibility: Open to Boston Harbor, Constitution Yacht Club, Cottage Park Yacht Club and Hingham Bay Racing handicap fleet members with a valid 2021 MBSA ORR-ez certificate. Entry: All yachts are requested to register for the Rumble events online at www.regattaman.com Fee: This event fee is included with your home fleet’s Twilight series fees. Notice to Competitors: Notices will be posted online at www.regattaman.com Signals Made Ashore: VHF channel 72. Please monitor your VHF as courses will be announced over the radio as well as posted on the Race Committee (RC) Boat. Schedule of Races: GBRS - Rumble II will consist of one race. Warning Signal: The First Warning Signal will be at 1830 Racing Area: GBRS - Rumble II will be held in the vicinity of Yellow Nun “E” (approximately 1 nm west of Deer Island Light in President Roads at approximately 042 20.22N 070,58.78W. All competitors are reminded to observe the Restricted Areas described in the Mass Bay Sailing Yearbook List C, especially those associated with Deer Island, Castle Island, and Nixes Mate. Boats shall not complete passage in either direction between Castle Island and Horn/Light “5”, Deer Island and Deer Island Light, Nixes Mate and Gallops Island and Deer Island and Great Faun Day Beacon R “6A”. -

Sculptors Gallery Proudly Hosts “34,” a Group Exhibition Curated by Liz Devlin of FLUX

!"#$"% #&'()$"*# +,((-*. !"#$%&'"(!) *++, 486 Harrison Ave, Boston,."t ! XXXCPTUPOTDVMQUPSTDPNtCPTUPOTDVMQUPST!ZBIPPDPN FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 7, 2015 Exhibition Title: 34 Exhibition Dates: July 22 – August 16, 2015 Artists’ Reception: July 26 from 3 – 5 pm SOWA First Friday Reception: August 7 from 5 – 8 pm Gallery Hours: Wed. – Sun. from 12 – 6 pm (Boston, MA): As a part of the Isles Arts Initiative, a summer long public art series on the Boston Harbor Islands and in venues across Boston, the Boston Sculptors Gallery proudly hosts “34,” a group exhibition curated by Liz Devlin of FLUX. Boston Sculptors Gallery will showcase work inspired by the intrinsic beauty and divergent tales of the Boston Harbor Islands National and State Park. “34” is a group exhibition that includes 34 regional artists each responding to one of the 34 Boston Harbor Islands. Each imaginative work will be accompanied by a placard, featuring text from Chris Klein’s Discovering the Boston Harbor Islands, which outlines a brief history of the particular island and will provide additional context for the work itself. The exhibition serves as a physical beacon on land that will be in conversation with the artwork on the harbor. Artists’ work will educate and inspire visitors, sharing unique perspectives and visionary iconography that will demonstrate why the islands’ history is among the most fascinating in our region. About Boston Sculptors: Founded in 1992, Boston Sculptors Gallery is an artist-run organization that presents and promotes innovative, challenging sculpture and installations. It is the only sculptors organization in the United States that maintains its own exhibition space. The organization has presented exhibitions of its sculptors in other venues and countries and occasionally invites Curators to present exhibitions in its gallery in Boston’s South End. -

Pirates and Buccaneers of the Atlantic Coast

ITIG CC \ ',:•:. P ROV Please handle this volume with care. The University of Connecticut Libraries, Storrs Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Lyrasis Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/piratesbuccaneerOOsnow PIRATES AND BUCCANEERS OF THE ATLANTIC COAST BY EDWARD ROWE SNOW AUTHOR OF The Islands of Boston Harbor; The Story of Minofs Light; Storms and Shipwrecks of New England; Romance of Boston Bay THE YANKEE PUBLISHING COMPANY 72 Broad Street Boston, Massachusetts Copyright, 1944 By Edward Rowe Snow No part of this book may be used or quoted without the written permission of the author. FIRST EDITION DECEMBER 1944 Boston Printing Company boston, massachusetts PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA IN MEMORY OF MY GRANDFATHER CAPTAIN JOSHUA NICKERSON ROWE WHO FOUGHT PIRATES WHILE ON THE CLIPPER SHIP CRYSTAL PALACE PREFACE Reader—here is a volume devoted exclusively to the buccaneers and pirates who infested the shores, bays, and islands of the Atlantic Coast of North America. This is no collection of Old Wives' Tales, half-myth, half-truth, handed down from year to year with the story more distorted with each telling, nor is it a work of fiction. This book is an accurate account of the most outstanding pirates who ever visited the shores of the Atlantic Coast. These are stories of stark realism. None of the arti- ficial school of sheltered existence is included. Except for the extreme profanity, blasphemy, and obscenity in which most pirates were adept, everything has been included which is essential for the reader to get a true and fair picture of the life of a sea-rover. -

Junior Ranger Program Booklet (Camping Islands)

Boston Harbor Islands National Park Area Bumpkin Island Green Island Nixes Mate Sheep Island Button Island Hangman Island Nut Island Slate Island Calf Island Langlee Island Outer Brewster Island Snake Island Deer Island Little Brewster Island Peddocks Island Spectacle Island Gallops Island Little Calf Island Raccoon Island Thompson Island Georges Island Long Island Ragged Island Webb Memorial Park Grape Island Lovells Island Rainsford Island Worlds End The Graves Middle Brewster Island Sarah Island Great Brewster Island Moon Island Shag Rocks Can’t turn in this booklet in person? Make a copy of your Junior Ranger Program Booklet completed booklet and send it with your name and address to: Boston Harbor Islands Junior Ranger Program 15 State St. Suite 1100 Camping Islands Boston, MA 02109 Activities created by Elisabeth Colby Designed and illustrated by Liz Cook Union Park Press, proud supporters of the Boston Harbor Islands National Park and publishers of Discovering the Boston Harbor Islands: A Guide to the City's Hidden Shores. A of Map Boston Harbor JUNIORJUNIOR RANGERRANGER NATIONAL PARK AREA N H O A T R EAST BOSTON B S O O R B SNAKE ISLAND THE GRAVES DEER ISLAND I GREEN ISLAND S S L A N D BOSTON LITTLE CALF ISLAND OUTER BREWSTER ISLAND CALF ISLAND MIDDLE BREWSTER ISLAND NIXES MATE GREAT BREWSTER ISLAND LOVELLS ISLAND SHAG ROCKS LITTLE BREWSTER ISLAND As a SPECTACLE ISLAND GALLOPS ISLAND LONG ISLAND Junior Ranger, THOMPSON ISLAND GEORGES ISLAND RAINSFORD ISLAND I pledge to: MOON ISLAND PEDDOCKS ISLAND • Continue learning about the