Birding the Boston Harbor Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Harbor Watersheds Water Quality & Hydrologic Investigations

Boston Harbor Watersheds Water Quality & Hydrologic Investigations Fore River Watershed Mystic River Watershed Neponset River Watershed Weir River Watershed Project Number 2002-02/MWI June 30, 2003 Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection Bureau of Resource Protection Boston Harbor Watersheds Water Quality & Hydrologic Investigations Project Number 2002-01/MWI June 30, 2003 Report Prepared by: Ian Cooke, Neponset River Watershed Association Libby Larson, Mystic River Watershed Association Carl Pawlowski, Fore River Watershed Association Wendy Roemer, Neponset River Watershed Association Samantha Woods, Weir River Watershed Association Report Prepared for: Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection Bureau of Resource Protection Massachusetts Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Ellen Roy Herzfelder, Secretary Department of Environmental Protection Robert W. Golledge, Jr., Commissioner Bureau of Resource Protection Cynthia Giles, Assistant Commissioner Division of Municipal Services Steven J. McCurdy, Director Division of Watershed Management Glenn Haas, Director Boston Harbor Watersheds Water Quality & Hydrologic Investigations Project Number 2002-01/MWI July 2001 through June 2003 Report Prepared by: Ian Cooke, Neponset River Watershed Association Libby Larson, Mystic River Watershed Association Carl Pawlowski, Fore River Watershed Association Wendy Roemer, Neponset River Watershed Association Samantha Woods, Weir River Watershed -

The Changing Flora of the Boston Harbor Islands

The Changing Flora of the Boston Harbor Islands Dale F. Levering, Jr. After more than three and one-half centuries of vicissitude, the deciduous forest that once covered the Boston Harbor islands may have begun to return Situated just to the north of the sandy, up- ing animals, the Eastern Deciduous Forest- lifted coastal plain of Cape Cod and just to the which was dominated by broad-leaved, south of the rocky coastline of northern New round-topped deciduous trees (as opposed to England, the Boston Harbor islands consti- needle-leaved, spire-topped evergreens)-was tute a unique maritime ecosystem. To the a richer source of food for the colonists than south of the Harbor, pines dominate the the evergreen forests to the north and south. sandy, mineral-deficient soil where the land No doubt this was one reason the English meets the sea; to the north, hemlock, white settled northward, rather than southward, pine, spruce, and fir. Some twenty thousand from Plymouth. years ago, when the Pleistocene ice sheet was The present-day vegetation of Moswe- at its maximum, the shoreline lay approxi- tusset Hummock, a small island situated at mately thirty miles east of where it does now; the northern end of Wollaston Beach in when the glacier first began to recede, what Quincy, is perhaps the closest indication we are now the Boston Harbor islands were ex- will ever have of what the Boston Harbor posed as high spots on what was then the islands’ vegetation looked like at the time of mainland. Alluvium from the Boston Basin English settlement. -

Boston University

BOSTON UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES Thesis BLUFF EVOLUTION AND GEOMORPHOLOGY OF THE BOSTON HARBOR DRUMLINS, MASSACHUSETTS by EMILY A. HIMMELSTOSS B.A., Franklin & Marshall College, 2000 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2003 Approved by First Reader ______________________________________________________ Duncan M. FitzGerald, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Earth Sciences Second Reader ______________________________________________________ David R. Marchant, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Earth Sciences ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This research was made possible through financial support from the National Park Service. Special thanks to Ms. Mary Foley, Regional Chief Scientist and Ms. Deborah DiQuinzio, Park Ranger, Natural Resource Management and Research Division of the Boston Support Office. I would have been unable to complete much of my research without help from my summer field assistant and friend Amy Webster, whose patience through all kinds of weather was greatly appreciated. I also owe gratitude to all of the graduate students in the Department of Earth Sciences at Boston University, whose good humor, helpful advice, and constant support gave me the needed strength to make it though many obstacles. Much appreciation is due to my wonderful parents, who have always been there for me. Finally I want to thank my boyfriend, Scott Ramsey, whose considerate nature and patience inspire me to be a better person. Special thanks are also due to my advisor, Duncan FitzGerald, and Peter Rosen who provided me with insight and good humor both in and out of the field. I would like to dedicate this thesis to the memory of Dr. James Allen of the United States Geological Survey a primary investigator on this project, who tragically passed away prior to its completion. -

Boston Harbor South Watersheds 2004 Assessment Report

Boston Harbor South Watersheds 2004 Assessment Report June 30, 2004 Prepared for: Massachusetts Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Prepared by: Neponset River Watershed Association University of Massachusetts, Urban Harbors Institute Boston Harbor Association Fore River Watershed Association Weir River Watershed Association Contents How rapidly is open space being lost?.......................................................35 Introduction ix What % of the shoreline is publicly accessible?........................................35 References for Boston Inner Harbor Watershed........................................37 Common Assessment for All Watersheds 1 Does bacterial pollution limit fishing or recreation? ...................................1 Neponset River Watershed 41 Does nutrient pollution pose a threat to aquatic life? ..................................1 Does bacterial pollution limit fishing or recreational use? ......................46 Do dissolved oxygen levels support aquatic life?........................................5 Does nutrient pollution pose a threat to aquatic life or other uses?...........48 Are there other water quality problems? ....................................................6 Do dissolved oxygen (DO) levels support aquatic life? ..........................51 Do water supply or wastewater management impact instream flows?........7 Are there other indicators that limit use of the watershed? .....................53 Roughly what percentage of the watersheds is impervious? .....................8 Do water supply, -

The Boston Harbor Project and the Reversal of Eutrophication of Boston Harbor

The Boston Harbor Project and the Reversal of Eutrophication of Boston Harbor Massachusetts Water Resources Authority Environmental Quality Department Report 2013-07 Citation: Taylor DI. 2013. The Boston Harbor Project and the Reversal of Eutrophication of Boston Harbor. Boston: Massachusetts Water Resources Authority. Report 2013-07. 33p. i THE BOSTON HARBOR PROJECT AND THE REVERSAL OF EUTROPHICATION OF BOSTON HARBOR Prepared by David I Taylor MASSACHUSETTS WATER RESOURCES AUTHORITY Environmental Quality Department and Department of Laboratory Services 100 First Avenue Charlestown Navy Yard Boston, MA 02129 (617) 242-6000 June 2013 Report No: 2013-01 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report draws on data collected by a number of monitoring projects. Grateful thanks are extended to the following Principal Investigators (PI) of these projects: Nancy Maciolek and James A. Blake AECOM Environment, Marine & Coastal Center, 89 Water Street, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA Anne E. Giblin and Jane Tucker The Ecosystems Center, Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA Robert J. Diaz Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary, Gloucester Pt., VA 23061, USA Charles T. Costello Division of Watershed Management, Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, 1 Winter Street, Boston MA 02108, USA Kelly Coughlin, Wendy Leo, Ken Keay, Laura Ducott ENQUAD, Massachusetts Water Resources Authority, 100 First Ave, Charlestown Navy Yard, MA 02129 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………. iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY………………………………………………………. 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………. 2 2.0 THE BOSTON HARBOR PROJECT (BHP) AND THE DECREASES IN INPUTS TO BOSTON HARBOR 2.1 Background on the BHP………………………………………… 3 2.2 Changes to the nutrient and organic matter inputs to the harbor…. -

Boston Harbor National Park Service Sites Alternative Transportation Systems Evaluation Report

U.S. Department of Transportation Boston Harbor National Park Service Research and Special Programs Sites Alternative Transportation Administration Systems Evaluation Report Final Report Prepared for: National Park Service Boston, Massachusetts Northeast Region Prepared by: John A. Volpe National Transportation Systems Center Cambridge, Massachusetts in association with Cambridge Systematics, Inc. Norris and Norris Architects Childs Engineering EG&G June 2001 Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER 5b. GRANT NUMBER 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

Research to Support Carrying Capacity Analysis at Boston Harbor Islands National Park Area

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Northeast Region Boston, Massachusetts Research to Support Carrying Capacity Analysis at Boston Harbor Islands National Park Area Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR-2006/064 ON THE COVER Little Brewster Island Light Photograph by: William Valliere Research to Support Carrying Capacity Analysis at Boston Harbor Islands National Park Area Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR-2006/064 Robert Manning Megha Budruk The University of Vermont Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources Burlington, Vermont 05405 October 2006 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Northeast Region Boston, Massachusetts The Northeast Region of the National Park Service (NPS) comprises national parks and related areas in 13 New England and Mid-Atlantic states. The diversity of parks and their resources are reflected in their designations as national parks, seashores, historic sites, recreation areas, military parks, memorials, and rivers and trails. Biological, physical, and social science research results, natural resource inventory and monitoring data, scientific literature reviews, bibliographies, and proceedings of technical workshops and conferences related to these park units are disseminated through the NPS/NER Technical Report (NRTR) and Natural Resources Report (NRR) series. The reports are a continuation of series with previous acronyms of NPS/PHSO, NPS/MAR, NPS/BSO-RNR and NPS/NERBOST. Individual parks may also disseminate information through their own report series. Natural Resources -

Weir River Area of Critical Environmental Concern Natural Resources Inventory

Weir River Area of Critical Environmental concern Natural Resources Inventory Massachusetts Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Massachusetts Watershed Initiative Department of Environmental Management Areas of Critical Environmental Concern (ACEC) Program August 2002 Jane Swift, Governor Bob Durand, Secretary, EOEA Peter C. Webber, Commissioner, DEM This document was prepared by Special thanks to Elizabeth Sorensen, Katie Urban Harbors Institute Lund, Jason Burtner, Karl Pastore, Margo University of Massachusetts Boston Clerkin, Straits Pond Watershed Association, 100 Morrissey Boulevard David Roach, Samantha Woods, Sally Avery, J. Boston, MA 02125 Hall, J. Lupos, B. McNamara, Ed Petrilak, and (617) 287.5570 Judith Van Hamm www.uhi.umb.edu Cover photo, Cory Riley Table Of Contents Index of Figures and 10. Land Use 37 Tables ii 11. Open Space and 1. Introduction 1 Recreation 40 12.1 World's End 40 2. Characteristics 12.2 Town of Hull 40 and Designation 5 12.3 Tufts University 41 12.4 Weir River Estuary Park 41 2.1 ACEC Background 5 2.2 Designation of ACEC 5 12. Recreation and Commercial Boating 43 3. Regional History 8 A. Hull 43 3.1 Archaeological Evaluation 7 B. Hingham 43 3.2 Local Industries 7 3.3 Straits Pond 8 13. Future Research 44 3.4 Flood History 9 4. Geology and Soils 11 Literature Cited 45 5. Watershed Appendix A - Natural Heritage Characteristics 12 Endangered Species Program 48 6. Habitats of the ACEC 14 6.1 Estuaries 14 Appendix B - Nomination and 6.2 Tidal Flats 14 Designation of the 6.3 Salt Marsh 14 Weir River ACEC 49 6.4 Shallow Marsh Meadow 15 Appendix C - World’s End Endangered 6.4 Eel Grass Beds 15 Species 58 6.5 Vernal Pools 15 7. -

(Osmerus Mordax) Spawning Habitat in the Weymouth- Fore River

Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Technical Report TR-5 Rainbow Smelt (Osmerus mordax) Spawning Habitat in the Weymouth- Fore River Bradford C. Chase and Abigail R. Childs Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Department of Fisheries, Wildlife and Environmental Law Enforcement Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Commonwealth of Massachusetts September 2001 Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Technical Report TR-5 Rainbow Smelt (Osmerus mordax) Spawning Habitat in the Weymouth-Fore River Bradford C. Chase and Abigail R. Childs Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Annisquam River Marine Fisheries Station 30 Emerson Ave. Gloucester, MA 01930 September 2001 Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Paul Diodati, Director Department of Fisheries, Wildlife and Environmental Law Enforcement Dave Peters, Commissioner Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Bob Durand, Secretary Commonwealth of Massachusetts Jane Swift, Governor ABSTRACT The spawning habitat of anadromous rainbow smelt in the Weymouth-Fore River, within the cities of Braintree and Weymouth, was monitored during 1988-1990 to document temporal, spatial and biological characteristics of the spawning run. Smelt deposited eggs primarily in the Monatiquot River, upstream of Route 53, over a stretch of river habitat that exceeded 900 m and included over 8,000 m2 of suitable spawning substrate. Minor amounts of egg deposition were found in Smelt Brook, primarily located below the Old Colony railroad embankment where a 6 ft culvert opens to an intertidal channel. The Smelt Brook spawning habitat is degraded by exposure to chronic stormwater inputs, periodic raw sewer discharges and modified stream hydrology. Overall, the entire Weymouth-Fore River system supports one of the larger smelt runs in Massachusetts Bay, with approximately 10,000 m2 of available spawning substrate. -

Winthrop Boat Ramp to Lovells Island, Boston Harbor. 9:45Am – 2:30Pm

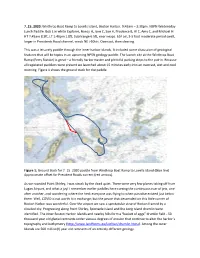

7_15_2020: Winthrop Boat Ramp to Lovells Island, Boston Harbor. 9:45am – 2:30pm. NSPN Wednesday Lunch Paddle. Bob L in white Explorer, Nancy H, Jane C, Sue H, Prudence B, Al C, Amy C, and Michael H. HT 7:45am 8.3ft, LT 1:46pm 1.8ft, tidal range 6.5ft, near neaps. 65F air, 3-5 foot moderate period swell, larger in Presidents Road channel, winds NE >10kts. Overcast, then clearing. This was a leisurely paddle through the inner harbor islands. It included some discussion of geological features that will be topics in an upcoming NPSN geology paddle. The launch site at the Winthrop Boat Ramp (Ferry Station) is great – a friendly harbormaster and plentiful parking steps to the put-in. Because all registered paddlers were present we launched about 15 minutes early into an overcast, wet and cool morning. Figure 1 shows the ground track for the paddle. Figure 1: Ground track for 7_15_2020 paddle from Winthrop Boat Ramp to Lovells Island (blue line) Approximate offset for President Roads current (red arrows). As we rounded Point Shirley, I was struck by the dead quiet. There were very few planes taking off from Logan Airport, and what a joy! I remember earlier paddles here cursing the continuous roar of jets, one after another, and wondering where the heck everyone was flying to when paradise existed just below them. Well, COVID is not worth it in exchange; but the peace that descended on this little corner of Boston Harbor was wonderful. Over the airport we saw a spectacular view of Boston framed by a clouded sky. -

Historically Famous Lighthouses

HISTORICALLY FAMOUS LIGHTHOUSES CG-232 CONTENTS Foreword ALASKA Cape Sarichef Lighthouse, Unimak Island Cape Spencer Lighthouse Scotch Cap Lighthouse, Unimak Island CALIFORNIA Farallon Lighthouse Mile Rocks Lighthouse Pigeon Point Lighthouse St. George Reef Lighthouse Trinidad Head Lighthouse CONNECTICUT New London Harbor Lighthouse DELAWARE Cape Henlopen Lighthouse Fenwick Island Lighthouse FLORIDA American Shoal Lighthouse Cape Florida Lighthouse Cape San Blas Lighthouse GEORGIA Tybee Lighthouse, Tybee Island, Savannah River HAWAII Kilauea Point Lighthouse Makapuu Point Lighthouse. LOUISIANA Timbalier Lighthouse MAINE Boon Island Lighthouse Cape Elizabeth Lighthouse Dice Head Lighthouse Portland Head Lighthouse Saddleback Ledge Lighthouse MASSACHUSETTS Boston Lighthouse, Little Brewster Island Brant Point Lighthouse Buzzards Bay Lighthouse Cape Ann Lighthouse, Thatcher’s Island. Dumpling Rock Lighthouse, New Bedford Harbor Eastern Point Lighthouse Minots Ledge Lighthouse Nantucket (Great Point) Lighthouse Newburyport Harbor Lighthouse, Plum Island. Plymouth (Gurnet) Lighthouse MICHIGAN Little Sable Lighthouse Spectacle Reef Lighthouse Standard Rock Lighthouse, Lake Superior MINNESOTA Split Rock Lighthouse NEW HAMPSHIRE Isle of Shoals Lighthouse Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse NEW JERSEY Navesink Lighthouse Sandy Hook Lighthouse NEW YORK Crown Point Memorial, Lake Champlain Portland Harbor (Barcelona) Lighthouse, Lake Erie Race Rock Lighthouse NORTH CAROLINA Cape Fear Lighthouse "Bald Head Light’ Cape Hatteras Lighthouse Cape Lookout Lighthouse. Ocracoke Lighthouse.. OREGON Tillamook Rock Lighthouse... RHODE ISLAND Beavertail Lighthouse. Prudence Island Lighthouse SOUTH CAROLINA Charleston Lighthouse, Morris Island TEXAS Point Isabel Lighthouse VIRGINIA Cape Charles Lighthouse Cape Henry Lighthouse WASHINGTON Cape Flattery Lighthouse Foreword Under the supervision of the United States Coast Guard, there is only one manned lighthouses in the entire nation. There are hundreds of other lights of varied description that are operated automatically. -

Public Notice

fr.iiiF.ll PUBLIC NOTICE ~ Comment Period Begins: April 11, 2017 us Anny Corps of Engineers e Comment Period Ends: May 11, 2017 New England District File Number: NAE-2016-1616 696 Virginia Road In Reply Refer To: Paul Sneeringer Concord, MA 01742-2751 Phone: (978) 318-8491 E-mail: [email protected] The District Engineer has received a permit application to conduct work in waters of the United States from the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) Waterway Office, 30 Shipyard Drive, Hingham, Massachusetts, 02043. This work is proposed within Boston Harbor adjacent to Spectacle Island, Peddocks Island, Georges Island and Gallops Island in Boston and Hull, Massachusetts. Massachusetts DCR proposes to install and to maintain a total of 161 commercial moorings around a number of the Boston Harbor islands in Boston and Hull, Massachusetts. The purpose for this project is to provide transient/ short-term mooring space and improved navigable access for boaters visiting the Boston Harbor Islands National Park. Massachusetts DCR, after coordination with the Island Alliance,.has taken responsibility for managing the 50 rental mooring previously authorized under Corps permit #200001090. Massachusetts DCR plans to relocate these moorings as described below. · In addition, they plan to install up to 111 additional commercial moorings as follows: Gallops Island - up to 11 moorings on the southeastern side of the island; Georges Island - up to 25 moorings on the northwestern side of the island; Peddocks Island- up to 75 moorings on the northwestern side of the island; and Spectacle Island - up to 50 moorings on the western side of the island.