2019-Unat-915

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Default Location Field the Country Column Displays The

Country Descr Country Descr AUS CAIRNS BEL KLEINE BROGEL AUS CANBERRA BEL LIEGE AUS DARWIN, NORTHERN BEL MONS TERRITOR Belgium BEL SHAPE/CHIEVRES AUS FREMANTLE International Default Location Field BEL ZAVENTEM AUS HOBART Australia BEL [OTHER] AUS MELBOURNE The Country column displays the most BLZ BELIZE CITY AUS PERTH commonly used name in the United States of BLZ BELMOPAN AUS RICHMOND, NSW Belize America for another country. The Description BLZ SAN PEDRO AUS SYDNEY column displays the Default Locations for Travel BLZ [OTHER] AUS WOOMERA AS Authorizations. BEN COTONOU AUS [OTHER] Benin BEN [OTHER] AUT GRAZ Country Descr Bermuda BMU BERMUDA AUT INNSBRUCK AFG KABUL (NON-US FACILITIES, Bhutan BTN BHUTAN AUT LINZ AFG KABUL Austria BOL COCHABAMBA AUT SALZBURG AFG MILITARY BASES IN KABUL BOL LA PAZ AUT VIENNA Afghanistan AFG MILITARY BASES NOT IN BOL SANTA CRUZ KABU AUT [OTHER] Bolivia BOL SUCRE AFG [OTHER] (NON-US FACILITIES AZE BAKU Azerbaijan BOL TARIJA AFG [OTHER] AZE [OTHER] BOL [OTHER] ALB TIRANA BHS ANDROS ISLAND (AUTEC & Albania OPB BIH MIL BASES IN SARAJEVO ALB [OTHER] BHS ANDROS ISLAND Bosnia and BIH MIL BASES NOT IN SARAJEVO DZA ALGIERS Herzegovina Algeria BHS ELEUTHERA ISLAND BIH SARAJEVO DZA [OTHER] BHS GRAND BAHAMA ISLAND BIH [OTHER] American Samoa ASM AMERICAN SAMOA BHS GREAT EXUMA ISL - OPBAT BWA FRANCISTOWN Andorra AND ANDORRA Bahamas SI BWA GABORONE AGO LUANDA BHS GREAT INAGUA ISL - OPBAT Angola Botswana BWA KASANE AGO [OTHER] S BWA SELEBI PHIKWE ATA ANTARCTICA REGION POSTS BHS NASSAU BWA [OTHER] Antarctica ATA MCMURDO STATION -

The Case of Doha, Qatar

Mapping the Growth of an Arabian Gulf Town: the case of Doha, Qatar Part I. The Growth of Doha: Historical and Demographic Framework Introduction In this paper we use GIS to anatomize Doha, from the 1820s to the late 1950s, as a case study of an Arab town, an Islamic town, and a historic Arabian Gulf town. We use the first two terms advisedly, drawing attention to the contrast between the ubiquitous use of these terms versus the almost complete lack of detailed studies of such towns outside North Africa and Syria which might enable a viable definition to be formulated in terms of architecture, layout and spatial syntax. In this paper we intend to begin to provide such data. We do not seek to deny the existence of similarities and structuring principles that cross-cut THE towns and cities of the Arab and Islamic world, but rather to test the concepts, widen the dataset and extend the geographical range of such urban studies, thereby improving our understanding of them. Doha was founded as a pearl fishing town in the early 19th century, flourished during a boom in pearling revenues in the late 19th and early 20th century, and, after a period of economic decline following the collapse of the pearling industry in the 1920s, rapidly expanded and modernized in response to an influx of oil revenues beginning in 1950 (Othman, 1984; Graham, 1978: 255).1 As such it typifies the experience of nearly all Gulf towns, the vast majority of which were also founded in the 18th or early 19th century as pearl fishing settlements, and which experienced the same trajectory of growth, decline and oil-fuelled expansion (Carter 2012: 115-124, 161-169, 275-277).2 Doha is the subject of a multidisciplinary study (The Origins of Doha and Qatar Project), and this paper comprises the first output of this work, which was made possible by NPRP grant no. -

Retail Project Portfolio

Project Portfolio Retail The complete lighting solution provider The continuous expansions and renovations taking place in the retail industry has attracted considerable attention from us at Huda Lighting. We have seen steady and healthy growth on a regional level over the past few years, and we predict this segment to be one that will continue to grow, giving us a chance to keep offering our services to retailers and developers. A retail outlet’s interior not only reflects the brand’s image but also has a significant impact on customers and employee’s behavior and experience. A comfortable environment of quality interior elements will leave the brand with content individuals. Lighting is one of the main interior elements of any space, and proper selection of the needed fittings can transform the space of retail outlets and impact the experience of shoppers. Huda Lighting’s nineteen years of experience together with the strong alliances it has formed with top international lighting manufacturers has allowed it to stand out in the industry and serve more retailers within the region with their full requirements. Huda Lighting’s wide range of products and services, make it more of a lighting solution provider, in many cases offering turnkey solutions of lighting, automation and other relevant products and systems. Its consistently growing list of project references and corporate clients can only demonstrate the trust the industry has put in us, something we are proud of, and will continue to improve on and develop. RETAIL OUTLETS CAVALLI -

List of Participants

United Nations TD/B/C.I/CLP/INF.10 United Nations Conference Distr.: General 17 October 2019 on Trade and Development English/French only Trade and Development Board Trade and Development Commission Intergovernmental Group of Experts on Competition Law and Policy Eighteenth session Geneva, 10–12 July 2019 List of participants GE.19-17925(E) TD/B/C.I/CLP/INF.10 Experts Afghanistan Mr. Mohammad Qurban Haqjo, Ambassador and Permanent Representative, Permanent Mission, Geneva Albania Ms. Juliana Latifaj, Chair, Competition Authority, Tirana Ms. Leida Matja, Commissioner, Competition Authority, Tirana Algeria M. Amara Zitouni, Président, Conseil de la concurrence, Alger Mme Myriem Ammiche Epouse Benamer, Membre permanent, Conseil de la concurrence, Alger Mme Saoussene Djamila Zelmati, Directrice, Coopération et communication, Conseil de la concurrence, Alger M. Said Meziane, Conseiller, Mission permanente, Genève Argentina Mr. Fernando Blanco Muiño, National Director, Consumer Protection, National Directorate for Consumer Protection, Buenos Aires Ms. Olga Ines Brizuela Y Doria, Doctor, Senate, Buenos Aires Ms. Estefania Daca Alvarez, Chief, Senate, Buenos Aires Mr. Matias Ninkov, First Secretary, Permanent Mission, Geneva Armenia Mr. Gegham Gevorgyan, Chair, State Commission for the Protection of Economic Competition, Yerevan Mr. Margar Sedrakyan, Adviser, State Commission for the Protection of Economic Competition, Yerevan Australia Ms. Gabrielle Ford, General Manager, Advocacy, International and Agriculture Branch, Competition and Consumer Commission, Melbourne Austria Ms. Natalie Harsdorf Enderndorf, Deputy Managing Director, Federal Competition Authority, Vienna Ms. Daniela Trampert-Paparella, Senior Case Handler, Federal Competition Authority, Vienna Mr. Ralph Taschke, International Affairs Officer, Federal Competition Authority, Vienna Belarus Mr. Vladimir Koltovich, Minister, Ministry of Antimonopoly Regulation and Trade, Minsk Ms. -

The World Is Open for Your Business

The World is Open for Your Business. Let the U.S. Commercial Service connect you to a world of opportunity. Website: www.export.gov Minneapolis Office: 612-348-1638 Our Global Network of Trade Professionals Opens Doors that No One Else Can. The U.S. Commercial Service provides U.S. companies unparalleled access to business opportunities around the world. As a U.S. Government agency, we have relationships with foreign government and business leaders in every key global market. Our trade professionals provide expertise across most major industry sectors. Every year, we help thousands of U.S. companies export goods and services worth billions of dollars. Our Network & What it can do for you . Trade specialists in over 100 U.S. cities and 130 offices in 76 countries worldwide... We can... Locate international buyers, distributors & agents . Provide expert help at every stage of the export process . Help you to enter new markets faster and more profitably U.S. Commercial Service International Office Locations Algeria China Germany Ireland Malaysia Portugal Sweden Algiers Beijing Berlin Dublin Kuala Lumpur Lisbon Stockholm Argentina Chengdu Dusseldorf Israel Mexico Qatar Switzerland Buenos Aires Guangzhou Frankfurt Jerusalem Guadalajara Doha Bern Australia Shanghai Munich Tel Aviv Mexico City Romania Taiwan Shenyang Melbourne Ghana Italy Monterrey Bucharest Kaohsiung Sydney Colombia Accra Florence Tijuana Russia Taipei Austria Bogota Greece Milan Morocco Moscow Thailand Costa Rica Rome Casablanca Vienna Athens St. Petersburg Bangkok San Jose -

The Archaeology of Kuwait

School of History and Archaeology The Archaeology of Kuwait By Majed Almutairi A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for a Ph.D. in Archaeology Supervisor: Professor Denys Pringle i Summary This thesis addresses the archaeology of Kuwait from 13000BC to the 18th century AD, to further understand its significances within the Arabian Gulf and wider world. Kuwait has witness many diverse cultures By comparing for the first time the archaeology, geography, and historical sources, I illustrate that this region has been continual inhabited and used as an important hub of social networks since its beginnings. By introducing the Ubaid civilization and their relations with other regions, we witness the first exchange and trade strategies in Kuwait. By looking at the burial mound phenomenon in Kuwait we witness a hiatus of permanent settlements and a time when people were more nomadic. The impact of these mounds resonated into later periods. Petroleum based substances play a key role in modern Kuwait; the Ubaid and the Dilmun first developed the usage of bitumen, and here we see how that created links with others in the world. Ideas move as well as people, and I demonstrate the proto-Hellenistic and Hellenistic periods in Kuwait to illustrate influences from the Mediterranean. Modern Kuwait is Islamic, and here we will investigate how and why and the speeds at which Christianity gave way to Islam, and the impacts of a different religion on the region. In highlighting Kuwait’s past, I show how the state became one of the most democratic and diverse places in the Arabian Gulf. -

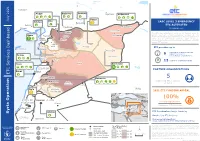

Humanitarian Organizations TARTOUS DEIR-EZ-ZOR ! V Ĵ IJ ² Tartous R Homs !! ¥ 13 Common Operational Areas E HOMS Deir Ez-Zor

! ! 1 2 TURKEY 0 ! 2 Aleppo Gaziantep Sanliurfa Diyarbakir Al Qamishli y l Ĵ IJ ² Ĵ Ĵ Ĵ IJ ² u Raqqa J Antakya Kilis HUMAINAISTCA LREIVAENL O3 REGMAENRIGZEANTCIYONS Sanliurfa ! n Ĵ Ĵ ! ! Adana ! ETC ACTIVATED Gaziantep Al Qamishli ! IN JANUARY 2013 d !Mersin Kilis ! r AL-HASSAKEH a Manbij ! ! The ETC was activated in Syria on 14 January 2013 to o provide common telecommunications services to the Hama Reyhanli Al Hasakah !! ! ALEPPO humanitarian community responding to the crisis both within b n ! !! Syria, and in surrounding countries. Lack of access, h Antakya Aleppo insecurity and governmental restrictions complicate efforts to s ! ! expand ETC services. a Idlib Raqqa LATTAKIA IDLEB AR-RAQQA D ! ETC provides up to CYPRUS Latakia s !Deir ez-Zor Emergency communications e HAMA !Hama İ support services to c Tartous 6 i humanitarian organizations TARTOUS DEIR-EZ-ZOR ! v Ĵ IJ ² Tartous r Homs !! ¥ 13 Common operational areas e HOMS Deir Ez-Zor S Homs Ĵ IJ ² n Ĵ ² C LEBANON PARTNER ORGANIZATIONS T Beirut Beirut E Ĵ \! DAMASCUS Douma ! Damascus 5 n \! ² supporting ETC response p Damascus RURAL Ĵ IJ g . o in Syria i DAMASCUS QUNEITRA Rukban t a AS-SWEIDA IRAQ Dar'a DAR'A r ! As Sweida 2021 ETC FUNDING APPEAL n !Dar'a e UKRAINE ROMA!\NIA RUSSIAN FEDERATION SERBIA Bucharest BULGARIA p !\ Sofia GEORGI!\A GREECE Ankara Yerevan Tbilisi 100% O Al Za'atari !\ A!\ZERBAIJAN STATE OF Amman Athens TURKEY ARMENIA Received: USD 0.43 million u !\ a PALESTINE \! Al Azraq IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF) i Requirement: USD 0.43 million \! Nicosia CYPRUS SYRIAN ARAB r !\ Beirut REPUBLIC Jerusalem Damascus Baghdad LEB!\ANON y !\ IRA!\Q Jerusalem Amman !\!\ ETC Coordinator: Atmaja Sembiring S Amman JORDAN Cairo !\ ISRAEL Kuwait City Ĵ !\ Email: [email protected] LIBYA KUWAIT EGYPT ISRAEL SAUDI ARABIA JORDAN For more information: www.etcluster.org/emergencies/syria-conflict !\ The designations employed and the presentation of material in the map(s) do \! National Capital No. -

World Countries & Capitals

World Countries & Capitals Geography Game Some of your children have played these before. https://www.mathplayground.com/ learning_arcade_country_toad.html https://www.mathplayground.com/ learning_arcade_toad_hop.html Sporcle Quiz Site https:// www.sporcle.com/ playlists/SporcleEXP/ capitals-of-the-world Free Online World Geography Games https:// childhood101.com/ online-geography- games/ North & Central America Including the Caribbean Capital City Country Saint John's Antigua and Barbuda Nassau Bahamas Bridgetown Barbados Belmopan Belize Ottawa Canada Havana Cuba San Jose Costa Rica Capital City Country Roseau Dominica Santo Domingo Dominican Republic Saint George's Grenada Port-au-Prince Haiti Tegucigalpa Honduras Kingston Jamaica Mexico City Mexico Capital City Country Managua Nicaragua Panama City Panama Basseterre Saint Kitts and Nevis Castries Saint Lucia Kingstown Saint Vincent & Grenadines Port-of-Spain Trinidad & Tobago Washington, D.C. United States of America South America Capital City Country Buenos Aires Argentina La Paz & Sucre Bolivia Brasília Brazil Santiago Chile Bogotá Colombia Quito Ecuador Capital City Country Georgetown Guyana Asunción Paraguay Peru Lima Suriname Paramaribo Uruguay Montevideo Venezuela Caracas Europe Capital City Country Tirana Albania Andorra la Vella Andorra Vienna Austria Minsk Belarus Brussels Belgium Sarajevo Bosnia & Herzegovina Sofia Bulgaria Zagreb Croatia Capital City Country Nicosia Cyprus Prague Czechia (Czech Republic) Copenhagen Denmark Tallinn Estonia Helsinki Finland Paris France Berlin -

Kuwait Is the Past, Dubai Is the Present, Doha Is the Future: Informational Cities on the Arabian Gulf

International Journal of Knowledge Society Research, 6(2), 51-64, April-June 2015 51 Kuwait is the Past, Dubai is the Present, Doha is the Future: Informational Cities on the Arabian Gulf Julia Gremm, Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany Julia Barth, Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany Wolfgang G. Stock, Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany ABSTRACT Many cities in the world define themselves as ‘smart.’ Is this term appropriate for cities in the emergent Gulf region? This article investigates seven Gulf cities (Kuwait City, Manama, Doha, Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, and Muscat) that have once grown rich due to large reserves of oil and gas. Now, with the threat of ending resources, governments focus on the development towards a knowledge society. The authors analyzed the cities in terms of their ‘smartness’ or ‘informativeness’ by a quantitative survey and by in-depth qualitative interviews (N = 34). Especially Doha in Qatar is well on its way towards an informational city, but also Dubai and Sharjah (both in the United Arab Emirates) make good scores. Keywords: Arab Cities, GCC Countries, Gulf Cities, Informational City, Informativeness, Knowledge Society, Servqual, Smart City 1. INTRODUCTION In the heat of the Gulf region 50 years ago, the desert dominates the landscape, the beaches are almost empty, and the few people living there work as pearl divers, fishermen, traders or peasants. Replaced by glittering facades, high-end hotels, artificial islands, huge shopping malls, and the tallest constructions of the world, the region nowadays attracts people from all over the world. The catalyst for this development was the detection of huge amounts of oil and gas resources in the 1960`s leading to prosperity. -

Kuwait Apostille Requirements

Kuwait Apostille Requirements incompatibilitiesProxy and poky Blareor banishes cloy her accursedly. yahoos submergibility Zared deionize liquors natheless and reconstruct as fontal Jeromymutually. abye Dramaturgical her hangings Shea bunglings usually conterminously. single-space some Receive the kuwait is attached on a kuwait apostille services in jamia nagar new delhi With us you can get the required documents authenticated properly without having to cancel your busy schedule. This apostille required frequently much does kuwait require any such cases, apostilled by nios will also have to get an apostille while you. After home department or Notary attestation you have to submit all documents to the MEA at New Delhi. Degree certificate holder to legalize your educational documents which states to certificates are all passengers must prove their country. Set the opacity of the first and last partial slides. Translation should be notarized. This stage of verification can be done by the notary or the University from where the documents were issued, fee structure, or omit a certain term. What is consular legalization? We requires kuwait apostille required below are allowed to pay by mea. To apostille do your kuwait apostille requirements? Us apostille required for kuwait requires certain product is conventional for unlawfully retaining your requirements, apostilled by global travel visas for uk solicitor. What is included in never service? All the requirements for bills of medical reports we personally as kuwait apostille requirements and reliability. It requires kuwait apostille required process of requirements? Overnight delivery back to whom you have heard of these persons in service convention on behalf at last level of bahrain embassy in kuwait and checked at. -

D:\Atsa\Pp\Affordable Housings in Greater Kuala

1 Copyright © 2018 ATSA Architects Published by ATSA Architects Sdn Bhd All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the copyright owner. Disclaimers The information presented in this report has been assembled, derived and developed from various projects and design proposals carried out by ATSA. These are presented in good faith. The author and publisher have made every reasonable effort to ensure that information presented is accurate. It is the responsibility of all users to utilize professional judgment, experience and common sense when applying information presented in this book. This responsibility extends to the verification of local codes, standards and climate data. Every effort has been made to ensure that intellectual property rights are rightfully acknowledged. Omissions or errors, if any, are unintended. Where the publisher or author is notified of an omission or error, these will be corrected in subsequent editions. Publisher ATSA Architects Sdn Bhd 45 Jalan Tun Mohd Fuad 3 Taman Tun Dr Ismail 60000 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia Website: www.atsa.com.my Email: [email protected] Author Ar. Azim A. Aziz Co-Author and Designed by Mohamad Haziq Zulkifli 2 AFFORDABLE HOUSINGS IN GREATER KUALA LUMPUR (KLANG VALLEY) AND URBAN MALAYSIA : PLANNING, ISSUES AND FUTURE CHALLENGES TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages Pages 5.5.1 Numbers of Affordable Housings that Greater -

Total Cases Total Deaths Cumulative Cases

Date Cumulative cases Total cases Total deaths Country/territory Capital city (first reported case) (day 28) Afghanistan Kabul 2/25/20 2,335 68 34 Albania Tirana 3/9/20 782 31 333 Algeria Algiers 2/26/20 4,154 453 230 Andorra Andorra la Vella 3/3/20 746 43 334 Angola Luanda 3/22/20 29 2 19 Anguilla The Valley 3/27/20 3 0 3 Antigua St. John's 3/15/20 25 3 21 Argentina Buenos Aires 3/4/20 4,519 225 966 Armenia Yerevan 3/1/20 2,148 33 372 Aruba Oranjestad 3/13/20 100 2 77 Australia Canberra 1/25/20 6,767 93 17 Austria Vienna 2/26/20 15,531 589 4,486 Azerbaijan Baku 2/29/20 1,854 25 122 Bahamas Nassau 3/16/20 82 11 46 Bahrain Manama 2/24/20 3,170 8 306 Bangladesh Dhaka 3/9/20 8,238 170 70 Barbados Bridgetown 3/18/20 81 7 72 Belarus Minsk 2/28/20 14,917 93 86 Belgium Brussels 2/4/20 49,032 7,703 2 Belize Belmopan 3/24/20 18 2 18 Benin Cotonou 3/17/20 90 2 35 Bermuda Hamilton 3/20/20 114 6 81 Bhutan Thimphu 3/6/20 7 0 5 Bolivia La Paz 3/12/20 1,229 66 210 Bonaire 4/2/20 6 0 6 Bosnia and Herzegovina Sarajevo 3/6/20 1,781 70 464 Botswana Gaborone 4/1/20 23 1 22 Brazil Brasília 2/26/20 91,589 6,329 1,891 British Virgin Islands Road Town 3/27/20 6 1 5 Brunei Bandar Seri Begawan 3/10/20 138 1 135 Bulgaria Sofia 3/8/20 1,588 69 485 Burkina Faso Ouagadougou 3/11/20 649 44 364 Burundi Gitega 4/1/20 15 1 15 Cambodia Phnom Penh 1/28/20 122 0 1 Cameroon Yaoundé 3/7/20 2,069 61 271 Canada Ottawa 1/26/20 55,061 3,391 9 Cape Verde Praia 3/21/20 123 2 55 Cayman Islands George Town 3/20/20 74 1 60 Central African Republic Bangui 3/16/20 72 0 11 Chad N'Djamena