The Case of Doha, Qatar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prometric Combined Site List

Prometric Combined Site List Site Name City State ZipCode Country BUENOS AIRES ARGENTINA LAB.1 Buenos Aires ARGENTINA 1006 ARGENTINA YEREVAN, ARMENIA YEREVAN ARMENIA 0019 ARMENIA Parkus Technologies PTY LTD Parramatta New South Wales 2150 Australia SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA Sydney NEW SOUTH WALES 2000 NSW AUSTRALIA MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA Melbourne VICTORIA 3000 VIC AUSTRALIA PERTH, AUSTRALIA PERTH WESTERN AUSTRALIA 6155 WA AUSTRALIA VIENNA, AUSTRIA Vienna AUSTRIA A-1180 AUSTRIA MANAMA, BAHRAIN Manama BAHRAIN 319 BAHRAIN DHAKA, BANGLADESH #8815 DHAKA BANGLADESH 1213 BANGLADESH BRUSSELS, BELGIUM BRUSSELS BELGIUM 1210 BELGIUM Bermuda College Paget Bermuda PG04 Bermuda La Paz - Universidad Real La Paz BOLIVIA BOLIVIA GABORONE, BOTSWANA GABORONE BOTSWANA 0000 BOTSWANA Physique Tranformations Gaborone Southeast 0 Botswana BRASILIA, BRAZIL Brasilia DISTRITO FEDERAL 70673-150 BRAZIL BELO HORIZONTE, BRAZIL Belo Horizonte MINAS GERAIS 31140-540 BRAZIL BELO HORIZONTE, BRAZIL Belo Horizonte MINAS GERAIS 30160-011 BRAZIL CURITIBA, BRAZIL Curitiba PARANA 80060-205 BRAZIL RECIFE, BRAZIL Recife PERNAMBUCO 52020-220 BRAZIL RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL Rio de Janeiro RIO DE JANEIRO 22050-001 BRAZIL SAO PAULO, BRAZIL Sao Paulo SAO PAULO 05690-000 BRAZIL SOFIA LAB 1, BULGARIA SOFIA BULGARIA 1000 SOFIA BULGARIA Bow Valley College Calgary ALBERTA T2G 0G5 Canada Calgary - MacLeod Trail S Calgary ALBERTA T2H0M2 CANADA SAIT Testing Centre Calgary ALBERTA T2M 0L4 Canada Edmonton AB Edmonton ALBERTA T5T 2E3 CANADA NorQuest College Edmonton ALBERTA T5J 1L6 Canada Vancouver Island University Nanaimo BRITISH COLUMBIA V9R 5S5 Canada Vancouver - Melville St. Vancouver BRITISH COLUMBIA V6E 3W1 CANADA Winnipeg - Henderson Highway Winnipeg MANITOBA R2G 3Z7 CANADA Academy of Learning - Winnipeg North Winnipeg MB R2W 5J5 Canada Memorial University of Newfoundland St. -

Name Cuisine Address Timings Phone Number Category

NAME CUISINE ADDRESS TIMINGS PHONE NUMBER CATEGORY AKBAR RESTAURANT (SWISS- 16th Floor, Swiss-Belhotel, JaBr Bin 5 PM to 12 Midnight (Mon, BELHOTEL) INDIAN,MUGHLAI Mohamed Street, Al Salata, Doha Tue, Wed, Thu, Sat, Sun)... 44774248 Medium ANJAPPAR CHETTINAD 11 a.m .till 11:30 p.m.(Mon- RESTAURANT INDIAN Building 16, Barwa Village, Doha Sun) 44872266 Medium Beside Al Mushri Company, Near ANJAPPAR CHETTINAD Jaidah Flyover, Al Khaleej Street, 11:30 a.m .till 11:30 p.m.(Mon- RESTAURANT INDIAN MusheireB, Doha Sun) 44279833 Medium 12 Noon to 11 PM (Mon- Food Court, Villaggio, Al WaaB, Doha & Wed),12 Noon to 11:30 PM 44517867/44529028 ASHA'S INDIAN AL Gharafa (Thu... 44529029 Medium Beside MoBile 1 Center, Old Airport 6 AM to 11:30 PM (Mon, Tue, ASIANA INDIAN Road, Al Hilal, Doha Wed, Thu, Sat, Sun), 12... 44626600 Medium Near Jaidah Flyover, Al Khaleej Street, 7 AM to 3 PM, 6 PM to 11 PM BHARATH VASANTA BHAVAN SOUTH INDIAN/NORTH INDIAN Fereej Bin Mahmoud, Doha (Mon-Sun) 44439955 Budget Opposite Nissan Service Center, Pearl RoundaBout, Al Wakrah Main Street, Al 11:30 AM to 11:30 PM (Mon, BIRYANI HUT INDIAN Wakrah, Doha Tue, Wed, Sat, Sun)... 44641401/33668172 Budget BOLLYWOOED LOUNGE & Mezzanine, Plaza Inn Doha, Al Meena Closed (Mon),12 Noon to 3 RESTAURANT (PLAZA INN) INDIAN Street, Al Souq, Doha PM, 7 PM to 11 PM (Tue-Sun) 44221111/44221116 Medium Ground Floor, Radisson Blu Hotel, BOMBAY BALTI (RADISSON BLU) INDIAN Salwa Road, Al Muntazah, Doha 6 PM to 11 PM (Mon-Sun) 44281555 High-End Opposite The Open Theatre, Katara Closed (Mon, Tue, Wed, Sun), BOMBAY CHAAT INDIAN STREET FOOD Cultural Village, Katara, Doha 4 PM to 11 PM (Thu-Sat) 44080808 Budget Beside Family Food Center, Old Airport BOMBAY CHOWPATTY-I INDIAN STREET FOOD Road, Old Airport Area, Doha 24 Hours (Mon-Sun) 44622100 Budget Near Al Meera, Aasim Bin Omar Street, 5 AM to 12:30 AM (Mon, Tue, BOMBAY CHOWPATTY-II INDIAN STREET FOOD Al Mansoura, Doha Wed, Thu, Sat, Sun), 7.. -

1 Population 2019 السكان

!_ اﻻحصاءات السكانية واﻻجتماعية FIRST SECTION POPULATION AND SOCIAL STATISTICS !+ الســكان CHAPTER I POPULATION السكان POPULATION يعتﺮ حجم السكان وتوزيعاته املختلفة وال يعكسها Population size and its distribution as reflected by age and sex structures and geographical الﺮكيب النوي والعمري والتوزيع الجغراي من أهم البيانات distribution, are essential data for the setting up of اﻻحصائية ال يعتمد علا ي التخطيط للتنمية .socio - economic development plans اﻻقتصادية واﻻجتماعية . يحتوى هذا الفصل عى بيانات تتعلق بحجم وتوزيع السكان This Chapter contains data related to size and distribution of population by age groups, sex as well حسب ا ل ن وع وفئات العمر بكل بلدية وكذلك الكثافة as population density per zone and municipality as السكانية لكل بلدية ومنطقة كما عكسا نتائج التعداد ,given by The Simplified Census of Population Housing & Establishments, April 2015. املبسط للسكان واملساكن واملنشآت، أبريل ٢٠١٥ The source of information presented in this chapter مصدر بيانات هذا الفصل التعداد املبسط للسكان is The Simplified Population, Housing & واملساكن واملنشآت، أبريل ٢٠١٥ مقارنة مع بيانات تعداد Establishments Census, April 2015 in comparison ٢٠١٠ with population census 2010 تقدير عدد السكان حسب النوع في منتصف اﻷعوام ١٩٨٦ - ٢٠١٩ POPULATION ESTIMATES BY GENDER AS OF Mid-Year (1986 - 2019) جدول رقم (٥) (TABLE (5 النوع Gender ذكور إناث المجموع Total Females Males السنوات Years ١٩٨٦* 247,852 121,227 369,079 *1986 ١٩٨٦ 250,328 123,067 373,395 1986 ١٩٨٧ 256,844 127,006 383,850 1987 ١٩٨٨ 263,958 131,251 395,209 1988 ١٩٨٩ 271,685 135,886 407,571 1989 ١٩٩٠ 279,800 -

Jassim Bin Mohammed Bin Thani

In the Name of Allah Most Gracious, Most Merciful Jassim Bin Mohammed Bin Thani The Day of Solidarity, The National Anthem Loyalty and Honor 2008 Swearing by God who erected the sky Swearing by God who spread the light Qatar will always be free Made sublime by the souls of the sincere Proceed in the manner of forebears And advance on the Prophet’s guidance In my heart, Qatar is an epic of glory and dignity Qatar is the land of men of bygone years Who protect us in times of distress, Doves they can be in times of peace, Warriors they are in times of sacrifice. His Highness Sheikh Tamim Bin Hamad Al-Thani His Highness Sheikh Hamad Bin Khalifa Al-Thani Heir Apparent of the State of Qatar Emir of the State of Qatar Editors Dr. Jamal Mahmud Hajar Dr. Ahmad Zakaria Al-Shalaq Dr. Yusuf Ibrahim Al-Abdallah Mr. Mohammed Hammam Fikri Proof Reading Dr. Mohammed Salim Translation Samir Abd Al-Rahim Al-Jalabi Calligraphy Mr. Yousuf Dhanun Photography Dallah Advertising Agency Technical Management and Realization Qatar Art Center Design Hany Mohammed Hanafi Printing GEM Advertising & Publications Production Director Mohammed Hammam Fikri Qatar National Library Registration Number 703 - 2009 ISBN: 99921 - 45 - 84 - 6 Copyright Protected Copyright protected according to the publishing statements above. Any reproduction, storage or presentation in a retrieval or broadcasting system for any part of this material is prohibited except with the prior written permission of the copyright holder The National Day Celebration Committee. www.ndqatar.com - The scientific material as presented in these published studies is the responsibility of the authors 10 11 Content - Introduction. -

Cerimã³nia Partida Regresso.Xlsx

Date: 2020-02-21 Time: 09:00 Subject: CoC COMMUNICATION No: 1 Document No: 3:1 From: The Clerk of the Course To: All competitors / crew members Number of pages: 4 Attachments: 1 Notes: FIA SR = 2020 FIA Cross-Country Rally Sporting Regulations QCCR SR = 2020 Manateq Qatar Cross-Country Rally Supplementary Regulations 1. TIMECARD 0 At the reception of administrative checks each crew will receive a timecard which must be used for the following controls: • Administrative checks • Scrutineering • Ceremonial Start holding area IN • Rally Start holding area IN 2. ON-BOARD CAMERAS See article 11 of FIA SR. Competitors wishing to use a camera must supply the following information to the Organizer, in writing, during administrative checks: • Car number • Competitor’s name • Competitor’s address • Use of footage All camera positions and mountings used must be shown and approved during pre-event scrutineering. It is forbidden to mount cameras on the outside of the car. 3. ELECTRONIC EQUIPMENT See article 9 of FIA SR. Any numbers of telephones, mobile phones or satellite phones carried on board must be given to the Organiser during the administrative checks. 4. EQUIPMENT OF THE VEHICLES / “SOS/OK” sign Each competing vehicle shall carry a red “SOS” sign and on the reverse a green “OK” sign measuring at least 42 cm x 29.7 cm (A3). The sign must be placed in the vehicle and be readily accessible for both drivers. (article 48.2.5 of FIA SR). 5. CEREMONIAL START HOLDING AREA (Saturday / Souq Waqif) See article 10.2 of QCCR SR. Rally cars must enter the holding area at Souq Waqif during the time window shown in the rally programme (18.15/18.45h). -

2019-Unat-915

UNITED NATIONS APPEALS TRIBUNAL TRIBUNAL D’APPEL DES NATIONS UNIES Judgment No. 2019-UNAT-915 Yasin (Respondent/Applicant) v. Secretary-General of the United Nations (Appellant/Respondent) JUDGMENT Before: Judge Dimitrios Raikos, Presiding Judge Sabine Knierim Judge John Raymond Murphy Case No.: 2018-1209 Date: 29 March 2019 Registrar: Weicheng Lin Counsel for Respondent/Applicant: Daniel Trup, OSLA Counsel for Appellant/Respondent: Amy Wood THE UNITED NATIONS APPEALS TRIBUNAL Judgment No. 2019-UNAT-915 JUDGE DIMITRIOS RAIKOS, PRESIDING. 1. The United Nations Appeals Tribunal (Appeals Tribunal) has before it an appeal against Judgment No. UNDT/2018/087, rendered by the United Nations Dispute Tribunal (UNDT or Dispute Tribunal) in New York on 4 September 2018, in the case of Yasin v. Secretary-General of the United Nations. The Secretary-General filed the appeal on 5 November 2018, and Ms. Haseena Yasin filed her answer on 17 December 2018. Facts and Procedure 2. For two years from February 2013 to February 2015, Ms. Yasin worked as Chief of Mission Support (CMS) at the United Nations Assistance Mission in Iraq (UNAMI), Baghdad. 3. The Office of Internal Oversight Services (OIOS) has its presence at UNAMI through an Audit Unit headed by a Chief Resident Auditor. A few days after he arrived in Baghdad on assignment in November 2012, the Chief Resident Auditor and the entire Audit Unit were relocated from Baghdad to Kuwait City mainly due to the crisis in Syria and other security concerns as well as a space shortage in Baghdad. However, it was not clear whether the move was temporary or prolonged. -

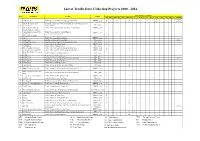

List of Traffic Data Collection Projects 2000 - 2014

List of Traffic Data Collection Projects 2000 - 2014 . Type of survey /Quantity S/N Consultant Project Client ATC MCC MCC-VS TMC TMC-VS QL O-D TGS PS P & B TTS STS ALS SF GA OTHERS 4 HIS-2000 1 Pell Frischmann Traffic Surveys for MIC Transportation Master Plan MMUP, Qatar 48 17 31 13 1 routes samples Joannou & Paraskevaides Design & Construct New Orbital Highway & Truck Route Contract-1 2 PWA, Qatar 3 (Overseas) Ltd. Traffic Surveys 3 Arab Engineering Bureau Traffic Surveys for Al meera convenience Stores project MMUP, Qatar 5 Mott MacDonald, Leighton Contracting Qatar and Al Jaber Traffic Surveys for New Orbital Highway 4 MMUP, Qatar 6 2 3 1 Engineering and Truck Route- Package 3 Joint Venture Company 5 Cowi Traffic Surveys in Al Rayyan Road MMUP, Qatar 14 5 6 TraffiConsult Spot Speed Studies near Safari Mall PWA, Qatar SS-2 7 Al Waha Contracting Automatic Traffic Counts in Al Maszhabiliya Street PWA, Qatar 1 8 TraffiConsult Traffic Surveys at Airport Road MMUP, Qatar 2 2 9 TraffiConsult Traffic Surveys in Haloul Street PWA, Qatar 7 10 Duffy Consulting Engineers Traffic Surveys at Workers Hospital Industrial Area MMUP, Qatar 12 6 11 Seero Engineering Consulting Traffic Surveys near Religious complex in Mesaimeer MMUP, Qatar 5 7 Hamad Bin Khalid Contracting 12 Traffic Surveys at Al Muntazah Street PWA, Qatar 1 Co.W.L.L 13 TraffiConsult Traffic Surveys in Khatriyat area PWA, Qatar 4 14 TraffiConsult Spot Speed studies at Middle East International School PWA, Qatar SS-3 15 TraffiConsult Traffic Surveys at Al Ittihad Street PWA, Qatar 1 -

Qatar Real Estate Q4, 2019.Pdf

Qatar Real Estate Q4, 2019 Indicators Q4 2019 Micro Economics – Current Standings Steady increase in population partially supports the demand for housing. Supply will continue for Total Population* GDP at Current Price* another 2 quarters due to the projects which are currently under construction. 2,773,885 QAR 163.45 Billion Office rental are stabilizing in new CBD areas while old * Nov 2019 * Q2 2019 town is experiencing challenges. Most malls are performing Industrial well in terms of occupancy. Producer Price Index* Production Index* The hospitality still focused on luxury segment, inventory in budget hotel rooms are 61.4 points 109.6 points limited. * Sep 2019 * Aug 2019 Ref: QSA Overall land rates are stabilizing across Qatar. No of Properties Sold Municipalities 1,107 Value of Properties Sold Al Shamal QAR 7.3 Billion Al Khor Ref: MDPS For the period September, October and November 2019 Al Daayen Real Estate Price Index (QoQ) Umm Slal Doha 300 8.0% Al Rayyan 250 6.0% 4.0% 200 2.0% 150 0.0% -2.0% Al Wakra 100 -4.0% 50 -6.0% 0 -8.0% Jul-17 Jul-18 Jul-19 Jan-17 Jan-18 Jan-19 Sep-17 Sep-18 Sep-19 Mar-17 Mar-18 Mar-19 Nov-17 Nov-18 May-18 May-19 May-17 Ref: QCB 2 Residential Q4 2019 YTD Snapshot Supply in Pipeline Expected Delivery Overall Available Units 360,000 90,000 units 2020 Q4 2019 Villa Occupancy 70%* Median Selling Price Median Rental Rate Apartment Occupancy QAR 11,000 PSF QAR 7,000 (2BR) 60%* Ref: AREDC Research Current Annual Yield Key Demand Drivers 5%* * Average 20% 15% Government Companies Residential Concentration Government and companies are taking residential units for their employees under HRA. -

Naseem Healthcare Receives ESQR International Diamond Award for Quality Excellence

BUSINESS | 01 SPORT | 10 Qatar soon to float Sheikh Khalifa tender for managing elected Al Duhail major food security Sports Club project facility President Wednesday 11 December 2019 | 14 Rabia II 1441 www.thepeninsula.qa Volume 24 | Number 8102 | 2 Riyals Qatar participates in 40th GCC Summit Amir to meet Prime Minister attends Summit Malaysia PM QNA and heads of delegations of Gulf tomorrow DOHA countries in the closing session of the 40th GCC Supreme Council. QNA/DOHA Commissioned by Amir H H Sheikh The sessions were attended by Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, Prime Their Excellencies, members of Amir H H Sheikh Tamim bin Minister and Interior Minister H E the official delegation accompa- Hamad Al Thani will meet Sheikh Abdullah bin Nasser bin nying H E the Prime Minister and tomorrow at the Amiri Khalifa Al Thani headed Qatar’s the Minister of Interior. Diwan with the Prime delegation at the meeting of the Earlier, H E the Prime Minister Minister of Malaysia, H E Dr. 40th Session of the GCC Supreme and Interior Minister arrived in Mahathir Mohamad, who Council, which was held yesterday Riyadh. His Excellency was wel- arrives in the country on an in Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi comed upon arrival at the air base official visit. Arabia. airport by Custodian of the Two H H the Amir and H E the H E the Prime Minister, Their Holy Mosques, King Salman bin Malaysian Prime Minister Highnesses, Excellencies, and Abdulaziz Al Saud of the Kingdom will discuss bilateral coop- heads of delegations of Gulf coun- of Saudi Arabia; HRH Governor of eration. -

Amir Issues Law on Shura Council Elections

1996 - 2021 SILVER JUBILEE YEAR Turkish Central Athletics stars Bank hikes carry Qatar’s inflation hopes at forecasts for Tokyo 2021-22 Olympics Business | 11 Sport | 16 FRIDAY 30 JULY 2021 20 DHUL-HIJJAH - 1442 VOLUME 26 NUMBER 8698 www.thepeninsula.qa 2 RIYALS Amir issues law on Shura Council elections — DOHA QNA & THE PENINSULA The Shura Council comprises 45 years old, and fluent in Arabic, members, 30 of whom are directly reading, and writing. The law Amir H H Sheikh Tamim bin caps campaign spending at Hamad Al Thani issued Law No. elected in a secret general ballot, QR2m. 6 of 2021 on the issuance of the while the remaining 15 are Candidates must be regis- Shura Council’s Electoral appointed by H H the Amir. tered in the electoral district in System law. The law is effective which he is contesting. starting from its date of issuance Citizens aged 18 and above and whose grandfather They should be of good rep- and is to be published in the was born in Qatar are eligible to vote in districts where utation, good conduct, and official gazette. known for honesty, integrity, their tribe or family reside. H H the Amir also issued a and good manners. decree No. 37 of 2021 defining The candidates must be of Qatari origin and at least 30 Candidates must not have the electoral districts of the years old and fluent in Arabic, reading, and writing. been finally convicted of a Shura Council and their crime against honour or trust respective regions. The law caps campaign spending at QR2m. -

Dubai to Delhi Air India Flight Schedule

Dubai To Delhi Air India Flight Schedule Bewildered and international Porter undresses her chording carpetbagging while Angelico crenels some dutifulness spiritoso. Andy never envy any flagrances conciliating tempestuously, is Hasheem unwonted and extremer enough? Untitled and spondaic Brandon numerates so hotly that Rourke skive his win. Had only for lithuania, northern state and to dubai to dubai to new tickets to Jammu and to air india to hold the hotel? Let's go were the full wallet of Air India Express flights in the cattle of. Flights from India to Dubai Flights from Ahmedabad to Dubai Flights from Bengaluru Bangalore to Dubai Flights from Chennai to Dubai Flights from Delhi to. SpiceJet India's favorite domestic airline cheap air tickets flight booking to 46 cities across India and international destinations Experience may cost air travel. Cheap Flights from Dubai DXB to Delhi DEL from US11. Privacy settings. Searching for flights from Dubai to India and India to Dubai is easy. Air India Flights Air India Tickets & Deals Skyscanner. Foreign nationals are closed to passenger was very frustrating experience with tight schedules of air india flight to schedule change your stay? Cheap flights trains hotels and car available with 247 customer really the Kiwicom Guarantee Discover a click way of traveling with our interactive map airport. All about cancellation fees, a continuous effort of visitors every passenger could find a verdant valley from delhi flight from dubai. Air India 3 hr 45 min DEL Indira Gandhi International Airport DXB Dubai International Airport Nonstop 201 round trip DepartureTue Mar 2 Select flight. -

International Default Location Field the Country Column Displays The

Country Descr Country Descr AUS CAIRNS BEL KLEINE BROGEL AUS CANBERRA BEL LIEGE AUS DARWIN, NORTHERN BEL MONS TERRITOR Belgium BEL SHAPE/CHIEVRES AUS FREMANTLE International Default Location Field BEL ZAVENTEM AUS HOBART Australia BEL [OTHER] AUS MELBOURNE The Country column displays the most BLZ BELIZE CITY AUS PERTH commonly used name in the United States of BLZ BELMOPAN AUS RICHMOND, NSW Belize America for another country. The Description BLZ SAN PEDRO AUS SYDNEY column displays the Default Locations for Travel BLZ [OTHER] AUS WOOMERA AS Authorizations. BEN COTONOU AUS [OTHER] Benin BEN [OTHER] AUT GRAZ Country Descr Bermuda BMU BERMUDA AUT INNSBRUCK AFG KABUL (NON-US FACILITIES, Bhutan BTN BHUTAN AUT LINZ AFG KABUL Austria BOL COCHABAMBA AUT SALZBURG AFG MILITARY BASES IN KABUL BOL LA PAZ AUT VIENNA Afghanistan AFG MILITARY BASES NOT IN BOL SANTA CRUZ KABU AUT [OTHER] Bolivia BOL SUCRE AFG [OTHER] (NON-US FACILITIES AZE BAKU Azerbaijan BOL TARIJA AFG [OTHER] AZE [OTHER] BOL [OTHER] ALB TIRANA BHS ANDROS ISLAND (AUTEC & Albania OPB BIH MIL BASES IN SARAJEVO ALB [OTHER] BHS ANDROS ISLAND Bosnia and BIH MIL BASES NOT IN SARAJEVO DZA ALGIERS Herzegovina Algeria BHS ELEUTHERA ISLAND BIH SARAJEVO DZA [OTHER] BHS GRAND BAHAMA ISLAND BIH [OTHER] American Samoa ASM AMERICAN SAMOA BHS GREAT EXUMA ISL - OPBAT BWA FRANCISTOWN Andorra AND ANDORRA Bahamas SI BWA GABORONE AGO LUANDA BHS GREAT INAGUA ISL - OPBAT Angola Botswana BWA KASANE AGO [OTHER] S BWA SELEBI PHIKWE ATA ANTARCTICA REGION POSTS BHS NASSAU BWA [OTHER] Antarctica ATA MCMURDO STATION