The Passing of John Hume

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ireland--The Healing Process

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Fordham University School of Law Fordham International Law Journal Volume 22, Issue 4 1998 Article 3 Ireland–The Healing Process John Hume∗ ∗ Copyright c 1998 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Ireland–The Healing Process John Hume Abstract As you are aware, the quarrel on our island has gone on for several centuries. Looking at the example of the conflict in Ireland, there are two mentalities in our quarrel - the Nationalist and the Unionist. The real political challenge to the Unionist mindset occurred when Nationalist Ireland essentially said: “Look, your objective is an honorable objective, the protection and preservation of your identity.” Geography, history, and the size of the Unionist tradition guarantee that the problem cannot be solved without them, nor against them. If we can leave aside our quarrel while we work together in our common interest, spilling our sweat and not our blood, we will break down the barriers of centuries, too, and the new Ireland will evolve based on agreement and respect for difference, just as the rest of the European Union has managed to achieve over the years–the healing process. That is the philosophy that I hope, at last, is going to emerge in your neighboring island of Ireland. I look forward to our island being the bridge between the United States of America and the United States of Europe. IRELAND-THE HEALING PROCESS John Hume* Ladies and gentleman, I am obviously very honored to re- ceive this doctorate from such a distinguished university as Ford- ham today and to hear your warm and strong support for the peace process in our country, particularly at this very crucial time in our history. -

The Nobel Peace Prize

TITLE: Learning From Peace Makers OVERVIEW: Students examine The Dalai Lama as a Nobel Laureate and compare / contrast his contributions to the world with the contributions of other Nobel Laureates. SUBJECT AREA / GRADE LEVEL: Civics and Government 7 / 12 STATE CONTENT STANDARDS / BENCHMARKS: -Identify, research, and clarify an event, issue, problem or phenomenon of significance to society. -Gather, use, and evaluate researched information to support analysis and conclusions. OBJECTIVES: The student will demonstrate the ability to... -know and understand The Dalai Lama as an advocate for peace. -research and report the contributions of others who are recognized as advocates for peace, such as those attending the Peace Conference in Portland: Aldolfo Perez Esquivel, Robert Musil, William Schulz, Betty Williams, and Helen Caldicott. -compare and contrast the contributions of several Nobel Laureates with The Dalai Lama. MATERIALS: -Copies of biographical statements of The Dalai Lama. -List of Nobel Peace Prize winners. -Copy of The Dalai Lama's acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize. -Bulletin board for display. PRESENTATION STEPS: 1) Students read one of the brief biographies of The Dalai Lama, including his Five Point Plan for Peace in Tibet, and his acceptance speech for receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace. 2) Follow with a class discussion regarding the biography and / or the text of the acceptance speech. 3) Distribute and examine the list of Nobel Peace Prize winners. 4) Individually, or in cooperative groups, select one of the Nobel Laureates (give special consideration to those coming to the Portland Peace Conference). Research and prepare to report to the class who the person was and why he / she / they won the Nobel Prize. -

Remarks at a Saint Patrick's Day Ceremony with Prime Minister

Mar. 17 / Administration of William J. Clinton, 1999 Your presence here today is a strong commit- Foley. I think we ought to rename the Speaker ment to the peace process and therefore grate- ‘‘O’Hastert’’ after—[laughter]—his words today, fully noted. And all I can say is, I think I can because they were right on point. speak for every Member of Congress in this So you know that across all the gulfs of Amer- room without regard to party, for every member ican politics, we join in welcoming all of our of our administration—you know that we feel, Irish friends. And right now, I’ll ask Taoiseach Taoiseach, almost an overwhelming and inex- Bertie Ahern to take the floor and give us a pressible bond to the Irish people. We want few remarks. to help all of you succeed. It probably seems Thank you, and God bless you. meddlesome sometimes, but we look forward to the day when Irish children will look at the Troubles as if they were some part of mystic Celtic folklore, and all of us who were alive NOTE: The President spoke at approximately noon during that period will seem like relics of a in Room H207 of the Rayburn House Office bygone history. Building. In his remarks, he referred to Father We hope we can help you to achieve that. Sean McManus, who gave the invocation; Prime And believe me, all of us are quite mindful Minister Bertie Ahern of Ireland; Social Demo- that it is much harder for you—every one of cratic and Labour Party leader John Hume; Ulster you here in this room who have been a part Unionist Party leader David Trimble; Sinn Fein of this—than it is for us. -

Xii World Summit of Nobel Peace Laureates

CHICAGO 23-25 April 2012 XII WORLD SUMMIT OF NOBEL PEACE LAUREATES «Speak up, speak out about your rights and freedoms» The World Summit of Nobel Peace Laureates: “A meeting of hope in the World” We invite all students and PhD students having fluent English and interested in international relations, globalization, geopolitics and international law to take part in XII World Summit of Nobel Peace Laureates. XII WORLD SUMMIT OF NOBEL PEACE LAUREATES is being organized by Permanent Secretariat of the World Summit of Nobel Peace laureates in cooperation with the City of Chicago (USA) and the magazine Time. The Summit will be held at the suggestion of the Gorbachev Foundation, Chicago City Hall, R. Kennedy Foundation and University of Illinois. Chaired by Mikhail Gorbachev and Walter Veltroni, the World Summit of Nobel Peace Laureates is among the most prestigious international appointments in the fields of peace, non-violence, social urgencies, ethnic, religious and cultural conflicts. The World Summit of Nobel Peace Laureates takes place every year since 1999. The last editions of the Summit were attended by 25 Nobel Peace Prize Laureates, 272 international media (including BBC, CNN, NBC, Al Jazeera), 700 delegates, 150 organisations and associations. Among the participants: Mikhail Gorbachev - H.H. The Dalai Lama - Muhammad Yunus - Oscar Arias Sanchez - Lech Walesa – Shimon Peres - Jose Ramos-Horta - David Trimble - John Hume - Kim Dae Yung – Joseph Rotblat, Jody Williams - Betty Williams - Mairead Corrigan Maguire - Philipe Ximenes Belo - Adolfo Perez Esquivel - Rigoberta Menchù Tum - Frederik Willem De Klerk - Unicef - Pugwash Conferences - I.P.P.N.W. - I.P.B. -

Revisionism: the Provisional Republican Movement

Journal of Politics and Law March, 2008 Revisionism: The Provisional Republican Movement Robert Perry Phd (Queens University Belfast) MA, MSSc 11 Caractacus Cottage View, Watford, UK Tel: +44 01923350994 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article explores the developments within the Provisional Republican Movement (IRA and Sinn Fein), its politicization in the 1980s, and the Sinn Fein strategy of recent years. It discusses the Provisionals’ ending of the use of political violence and the movement’s drift or determined policy towards entering the political mainstream, the acceptance of democratic norms. The sustained focus of my article is consideration of the revision of core Provisional principles. It analyses the reasons for this revisionism and it considers the reaction to and consequences of this revisionism. Keywords: Physical Force Tradition, Armed Stuggle, Republican Movement, Sinn Fein, Abstentionism, Constitutional Nationalism, Consent Principle 1. Introduction The origins of Irish republicanism reside in the United Irishman Rising of 1798 which aimed to create a democratic society which would unite Irishmen of all creeds. The physical force tradition seeks legitimacy by trying to trace its origin to the 1798 Rebellion and the insurrections which followed in 1803, 1848, 1867 and 1916. Sinn Féin (We Ourselves) is strongly republican and has links to the IRA. The original Sinn Féin was formed by Arthur Griffith in 1905 and was an umbrella name for nationalists who sought complete separation from Britain, as opposed to Home Rule. The current Sinn Féin party evolved from a split in the republican movement in Ireland in the early 1970s. Gerry Adams has been party leader since 1983, and led Sinn Féin in mutli-party peace talks which resulted in the signing of the 1998 Belfast Agreement. -

Acceptance of Diversity: the Essence of Peace in the North of Ireland

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 18, Issue 4 1994 Article 3 Acceptance of Diversity: The Essence of Peace in the North of Ireland John Hume∗ ∗ Copyright c 1994 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Acceptance of Diversity: The Essence of Peace in the North of Ireland John Hume Abstract True unity, as I have said, is based on respect for diversity. In Ireland, we must build political institutions that reflect the diversity of all our people, both North and South. These institutions will allow us to work together in our common economic interests to create hope for all our people. In time, the old sectarian barriers will break down and, in a generation or two, we will see a new Ireland. It will be very different from the models traditionally suggested by unionists and nationalists because it will be built on consensus and acknowledge the diversity of our people. The complete cessation of violence in the North of Ireland for the first time in twenty-five years has created a great opportunity to move towards consensus. ADDRESS ACCEPTANCE OF DIVERSITY: THE ESSENCE OF PEACE IN THE NORTH OF IRELAND John Hume* There are many people in the North of Ireland' who have experienced little but despair over the past twenty-five years. Providing these people with hope and encouragement is an im- portant part of the current peace process. The tremendous in- * Co-founder and leader of Ireland's Social Democratic and Labour Party; Mem- ber, U.K. -

Annual Report 2017 Dialogue in Divided Societies

Annual Report 2017 Dialogue in Divided Societies Presented by It is a great honor for Augsburg University to be host and home to the Nobel Peace Prize Forum in Minneapolis with our many organizing partners, including the University of Minnesota. On behalf of all the student and faculty attendees, thank you for supporting us in the work of sending out into the world better informed and equipped peacemakers. — Paul C. Pribbenow, Augsburg University President GREETINGS FROM THE PROGRAM DIRECTOR reetings from the office of the Nobel Peace Prize Forum, hosted at Augsburg University. It has been a momentous year, with the return of the Forum to the Augsburg campus as we marked our transition from a college to a university. This year’s return to campus and the Cedar-Riverside community refocused on both student and community involvement, with an increased emphasis on action and engagement with ongoing peacemaking efforts. The Grepresentatives of the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet—our honored laureates this year—were gracious, wise, and good-humored. It was easy to see how they were able to bring together the fractious parties in Tunisia to foster a pluralistic democratic system during a time of serious risks of social fragmentation and violence. More than 1,700 people attended the 2017 Forum, triple the level from 2016, and this year’s participants engaged with a rich array of accomplished guests and speakers. We were pleased to host the Secretary of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, Olav Njølstad, and appreciated his willingness to participate during the busy weeks leading up to the October 6 announcement of the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize recipient. -

President Clinton's Meetings & Telephone Calls with Foreign

President Clinton’s Meetings & Telephone Calls with Foreign Leaders, Representatives, and Dignitaries from January 23, 1993 thru January 19, 20011∗ 1993 Telephone call with President Boris Yeltsin of Russia, January 23, 1993, White House declassified in full Telephone call with Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin of Israel, January 23, 1993, White House Telephone call with President Leonid Kravchuk of Ukraine, January 26, 1993, White House declassified in full Telephone call with President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt, January 29, 1993, White House Telephone call with Prime Minister Suleyman Demirel of Turkey, February 1, 1993, White House Meeting with Foreign Minister Klaus Kinkel of Germany, February 4, 1993, White House Meeting with Prime Minister Brian Mulroney of Canada, February 5, 1993, White House Meeting with President Turgut Ozal of Turkey, February 8, 1993, White House Telephone call with President Stanislav Shushkevich of Belarus, February 9, 1993, White House declassified in full Telephone call with President Boris Yeltsin of Russia, February 10, 1993, White House declassified in full Telephone call with Prime Minister John Major of the United Kingdom, February 10, 1993, White House Telephone call with Chancellor Helmut Kohl of Germany, February 10, 1993, White House declassified in full Telephone call with UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali, February 10, 1993, White House 1∗ Meetings that were only photo or ceremonial events are not included in this list. Meeting with Foreign Minister Michio Watanabe of Japan, February 11, 1993, -

A Collection of Essays

A Collection of Essays TEN YEARS OF THE CLINTON PRESIDENTIAL CENTER 2004 – 2014 AN IMPACT THAT ENDURES By Chelsea Clinton When my family left the White House, my father faced a set of questions and opportunities about how to continue the work he had long championed through elected office as a private citizen. As he has said, while President, he confronted a seemingly endless horizon of challenges on any given day. Through the Clinton Foundation and its various initiatives, by necessity and deliberate choice, he has focused on tackling those urgent challenges which can be addressed outside government and on which he, and now our whole family, can have the most significant impact. What has not changed is what has always motivated my father —will people be better off when he’s done than when he started. I am grateful he hasn’t stopped yet—and has no plans to do so. The collection of essays that follows offers a window onto the various ways in which my father has served, in and out of elected office, and in the United States and around the world. Common threads emerge, in addition to how he keeps score of his own life, including a fearlessness to take on ostensibly impossible issues, a determination to see things through until the end and a belief that every success only contains another challenge to do things better next time. Because, as my father knows all too well, all too often there is a next time. The latter half of 2014 has been momentous in our family as Marc and I welcomed our daughter Charlotte into the world and my parents (finally) became grandparents. -

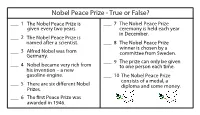

Nobel Peace Prize - True Or False?

Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___ 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___ 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. ceremony is held each year in December. ___ 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___ 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a ___ 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. ___ 9 T he prize can only be given ___ 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. his invention – a new gasoline engine. ___ 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money. Prizes. ___ 6 The rst Peace Prize was awarded in 1946 . Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___F 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___T 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. Every year ceremony is held each year in December. ___T 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___F 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a Norway ___F 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. Sweden ___F 9 T he prize can only be given ___F 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. Two or his invention – a new more gasoline engine. He got rich from ___T 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize dynamite T consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money. -

A Prize Worth Having? Paul Rogers

OxfordResearchGroup | September 2009 International Security Monthly Briefing – September 2009 A Prize Worth Having? Paul Rogers When the Nobel Peace Prize was announced there was surprise if not astonishment in many circles. This year’s prize had been considered to be very open, but several potential recipients had been identified, including Pieda Cordoba of Colombia, Prince Ghazi bin Muhammad of Jordan and Dr Sima Sanar of Afghanistan. These and others were people involved in long-term human rights activism or specific campaigns on issues such as inter-faith dialogue. The awarding of the prize to President Barack Obama was far from being the first time that it had gone to a head of state or other leading political figure, but on most previous occasions it had been for defined achievements over some years. In the case of President Obama, the award was “for his extraordinary efforts to strengthen international diplomacy and cooperation between peoples”, but critics pointed to the very short space of time involved, with the nominating process actually having been completed within days of his taking office last January. A consequence of the decision was very strong opposition from the political right in the United States, sometimes bordering on apoplexy and frequently seeing it as interference in domestic policies, especially at a time of intensive controversy over health care reform. There were also criticisms from progressive circles, mainly that the prize committee should not have made the award to a politician who, whatever the changes he was seeking, was still involved in a war in Iraq, and was considering an escalation in Afghanistan and heavier involvement in counter-insurgency in Pakistan. -

SEAN MACBRIDE PEACE PRIZE 2014 Awarded to the People and Government of the Marshall Islands

SEAN MACBRIDE PEACE PRIZE 2014 Awarded to the People and Government of the Marshall Islands It is known as a tropical paradise.. But the Marshall Islands have also suffered from the nuclear testing inflicted on their country by the USA from 1946 to 1958 For decades they have resisted the abuse of their islands and protested the serious effects on their health 1 Now the islanders have decided to take the nuclear states to court… On April 24, 2014, The Marshall Islands filed unprecedented lawsuits in the International Court of Justice and U.S. Federal Court to hold the nine nuclear-armed nations accountable for flagrant violations of international law with respect to their nuclear disarmament obligations under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and customary international law. Some 73 civil society leaders from 22 countries around the world have lent their support to the people and government of the Marshall Islands and the Nuclear Zero Lawsuits. For this courageous decision the International Peace Bureau will award them the 2014 Sean MacBride Peace Prize, given every year to a person or organisation that has made an outstanding contribution to peace, disarmament and/or human rights. SEAN MACBRIDE These were the principal concerns of Sean MacBride, the distinguished Irish statesman who was Chairman of IPB from 1968-74 and President from 1974-1985. MacBride began his career as a fighter against British colonial rule, studied law and rose to high office in the independent Irish Republic. He was a winner of the Lenin Peace Prize, and also the Nobel Peace Prize (1974) – awarded for his wide-ranging work, which included roles such as co-founder of Amnesty International, Secretary-General of the International Commission of Jurists, and UN Commissioner for Namibia.