Der Stein Der Weisen and Die Zauberflöte

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

|||GET||| the Cambridge Mozart Encyclopedia 1St Edition

THE CAMBRIDGE MOZART ENCYCLOPEDIA 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Cliff Eisen | 9780521712378 | | | | | Professor Simon McVeigh Beginning on measure 26, the first violins, cellos and basses blends alongside with the horns bassoons in a The Cambridge Mozart Encyclopedia 1st edition motive see Ex. The tale of a storm and snow is false; the day was calm and mild. References [1] Solomon, Maynard Relations with Nannerl Wolfgang left home permanently in see belowand from this time untilLeopold lived in Salzburg with just Nannerl now in her early thirties and their servants. Robert N. Essentially, the composer utilizes motivic materials from the exposition and its introduction to quickly thwart the listener The Cambridge Mozart Encyclopedia 1st edition ambiguous and seemingly unstable tonal centers. The move almost certainly aided Wolfgang's musical development; the great majority of his most celebrated works were composed in Vienna. Rupert's Cathedral. Glover, Jane Mozart biographer Maynard Solomon has taken a particularly harsh view of Leopold, treating him as tyrannical, mendacious, and possessive; Ruth Halliwell adopts a far more sympathetic view, portraying his correspondence as a sensible effort to guide the life of a grossly irresponsible Wolfgang. In: Christina Bashford and Leanne Langley, eds. Be the first to write a review About this product. Sadie and F. SolomonSolomonDeutschDavenport"The Emperor Leopold II was to be crowned king of Bohemia in early September and the national States assembly at Prague had sent Wolfgang a commission to write the festival opera. Previously, Keefe music, City Univ. Michael Curtis marked it as to-read Jan 16, If not, I know no better remedy than to marry Constanze tomorrow morning or if possible today. -

The Magic Flute

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART the magic flute conductor Libretto by Emanuel Schikaneder Harry Bicket Saturday, December 29, 2018 production 1:00–2:45 PM Julie Taymor set designer George Tsypin costume designer Julie Taymor lighting designer The abridged production of Donald Holder The Magic Flute was made possible by a puppet designers Julie Taymor gift from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Michael Curry and Bill Rollnick and Nancy Ellison Rollnick choreographer Mark Dendy The original production of Die Zauberflöte was made possible by a revival stage director David Kneuss gift from Mr. and Mrs. Henry R. Kravis english adaptation J. D. McClatchy Additional funding was received from John Van Meter, The Annenberg Foundation, Karen and Kevin Kennedy, Bill Rollnick and Nancy Ellison Rollnick, Mr. and Mrs. William R. general manager Miller, Agnes Varis and Karl Leichtman, and Peter Gelb Mr. and Mrs. Ezra K. Zilkha jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The Magic Flute is The 447th Metropolitan Opera performance of performed without intermission. WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART’S This performance is being broadcast the magic flute live over The Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Opera conductor International Radio Harry Bicket Network, sponsored by Toll Brothers, in order of vocal appearance America’s luxury ® tamino second spirit homebuilder , with Ben Bliss* Eliot Flowers generous long- first l ady third spirit term support from Gabriella Reyes** N. Casey Schopflocher the Annenberg Foundation and second l ady spe aker GRoW @ Annenberg, Emily D’Angelo** Alfred Walker* The Neubauer Family third l ady sar astro Foundation, the Maria Zifchak Morris Robinson* Vincent A. -

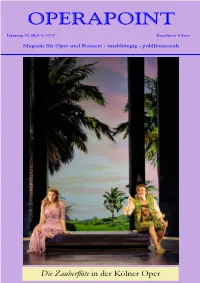

Opeapoint 4 Jg20.Indd

OPERAPOINT Jahrgang 20, Heft 4, 2020 Einzelpreis 6 Euro Magazin für Oper und Konzert - unabhängig - publikumsnah Die Zauberfl öte in der Kölner Oper Hier lege ich Ihnen, liebe Lesergemeinde, das 4. Heft 2020 vor. Diesmal wird es durch die verschiedenen Festivals ermöglicht, zwölf Opernrezen- Editorial sionen vorzustellen. Die meisten Kritiken verdanken wir unserem uner- müdlichen Redakteur Oliver Hohlbach. Er durchfährt mit viel Courage die deutschen und ausländischen Länder und erläutert mit Sachverstand die vorgeschriebenen Verordnungen der Regierungen, die dem Volk die Ansteckungen des Virus ersparen wollen. Den Sommerurlaub verbrachte unser Boardmitglied Dr. Martin Knust auf einem Segeltörn in Schweden. Es läßt seine Bürger trotz Virusge- fahr – trotz erheblicher Kritik vieler Länder – frei handeln. In der Nähe Stockholms gibt es eine ausgedehnte Schärenlandschaft. Dr. Knust schil- dert neben der Landschaft mit vielen eindrucksvollen Seebildern auch den schwedischen Komponisten Hugo Alfvén, der kaum jemand der Leser- schaft bekannt seine dürfte, dessen Werke aber großen Hörgenuß berei- ten. Auch in Köln gab es die Oper Die Zauberfl öte ohne Kürzungen in der bewährten Regie von Michael Hampe, dessen unvergeßlicher Zeiten als Kölner Opernintendant von zwei Jahrzehnten 1975-1995 man sich in der jetzigen Theaterinstanz entsann und ihn zu dieser Inszenierung eingela- den hat. Die reduzierten Opernbesucher quittierten seine intelligente und gekonnte Leistung mit starkem Applaus. Die Sängerschar der Premiere, die ich am 3. Oktober 2020 besuchte, ist über die Maßen zu loben. Einer davon, der französische Tenor Julien Behr, war bereit, mir ein Interview zu gewähren, das Sie auf Seite 15 lesen können. Eine der Erscheinungen, die diese Zeiten hervorgebracht haben, ist die Entdeckung der Sächsischen Landschaft in Deutschland. -

'The Philosopher's Stone': Mozart's Newly Discovered Opera

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 27, Number 4, January 28, 2000 Review ‘The Philosopher’s Stone’: Mozart’s newly discovered opera by David M. Shavin Philosopher’s Stone, the famous “Miau! Miau!” duet that opens the Finale of Act II. (This assumption had been based The Philosopher’s Stone, or upon a known copy of this “cat duet” in Mozart’s hand.) Since The Enchanted Isle Mozart had contributed individual works to several operas by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Johann Baptist by others, nothing much was made of this. Now, Buch has Henneberg, Benedikt Schack, Franz Xaver Gerl, and Emanuel Schikaneder identified Mozart as the main composer of the Act II Finale, A fairy-tale opera from 1790, rediscovered by along with the Act II duet, “Nun, liebes Weibchen.” Schik- David J. Buch aneder, who is credited with two of the works in The Philoso- Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman, Telarc CD pher’s Stone, was the creator of the comic figure Papageno, in The Magic Flute. Further, the other three collaborators inThe Philosopher’s The discovery of Mozart’s significant role in the opera The Stone also played major roles in The Magic Flute production Philosopher’s Stone casts a whole new light on his famous the following year. Johann Baptist Henneberg, who has 10 of opera The Magic Flute. This recording presents the long-lost the 24 attributions in The Philosopher’s Stone, including most half-sister. It is also something of a minor miracle that the of Act I, was the conductor for The Magic Flute (except when opera, a product of the collaboration of five composers, is as Mozart himself chose to conduct). -

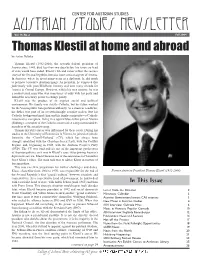

Fall 04 9-16.Idd

CENTER FOR AUSTRIAN STUDIES AUSTRIAN STUDIES NEWSLETTER Vol. 16, No. 2 Fall 2004 Thomas Klestil at home and abroad by Anton Pelinka Thomas Klestil (1932-2004), the seventh federal president of Austria since 1945, died less than two days before his tenure as head of state would have ended. Klestil’s life and career reflect the success story of the Second Republic, but also some critical aspects of Austria. In America, where he spent many years as a diplomat, he did much to promote a positive Austrian image. As president, he tempered that judiciously with post-Waldheim honesty and won many friends for Austria in Central Europe. However, within his own country, he was a controversial man who was sometimes at odds with his party and lacked the necessary power to change policy. Klestil was the product of an atypical social and political environment: His family was strictly Catholic, but his father worked for the Vienna public transportation authority. As a streetcar conductor, his father was part of an overwhelmingly socialist milieu. But his Catholic background made him and his family a minority—a Catholic conservative exception, living in a typical blue-collar part of Vienna (Erdberg); a member of the Catholic conservative camp surrounded by members of the socialist camp. Thomas Klestil’s career was influenced by these roots. During his studies at the University of Economics in Vienna, he joined a Catholic fraternity—the “Cartell-Verband” (CV), which has always been strongly identified with the Christian Social Party, with the Dollfuß Regime and, beginning in 1945, with the Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP). -

Spring 2000 Forum on Austrian Government and EU Draws Overflow Crowd by Daniel Pinkerton

AUSTRIAN CENTERSTUDIES FOR AUSTRIAN STUDIESNEWSLETTER Vol. 12, No. 2 Spring 2000 Forum on Austrian government and EU draws overflow crowd by Daniel Pinkerton The news that the right of center People’s Party (ÖVP) and the contro- versial conservative Freedom Party (FPÖ) would form a coalition govern- ment thrust Austria on to the world’s stage and into America’s newspa- pers. When, on 31 January, 14 mem- ber states of the European Union announced a series of vague bilateral sanctions against Austria, the subject became front page news. Locally, headlines were alarming and stories were brief and occasion- ally distorted. Clearly there was a need for a serious, informative debate to shed light on Austria’s difficulties; therefore, the Center quickly orga- nized a panel discussion, “Austria and the Haider Phenomenon: Democracy, National Identity, and the European The panelists, left to right: Thomas Wolfe, David Good, Helga Leitner, Eric Weitz, and W. Phillips Shiveley. Union.” Held on 16 February, and drawing from the rich pool of talent on the University of Minnesota’s reacted somewhat, and its well-meaning sanctions were vague and pre- faculty, the forum (cosponsored by the Center for German and European mature. Most Austrians did not vote for the FPÖ and the coalition has not Studies) drew an overflow crowd of about 125 people, forcing an instant proposed any legislation that violates any EU tenets. change of venue from the original room to the Humphrey Institute’s Days later, an appreciative and better-informed community was still Cowles Auditorium. The audience consisted of community members and talking about Austria, and the Center had received numerous congratula- students, staff, and faculty from the University of Minnesota as well as tions for hosting this timely event. -

Komponisten 1618Caccini

© Albert Gier (UNIV. BAMBERG), NOVEMBER 2003 KOMPONISTEN 1618CACCINI LORENZO BIANCONI, Giulio Caccini e il manierismo musicale, Chigiana 25 (1968), S. 21-38 1633PERI HOWARD MAYER BROWN, Music – How Opera Began: An Introduction to Jacopo Peri´s Euridice (1600), in: The Late Italian Renaissance 1525-1630, hrsg. von ERIC COCHRANE, London: Macmillan 1970, S. 401-443 WILLIAM V. PORTER, Peri and Corsi´s Dafne: Some New Discoveries and Observations, Journal of the American Musicological Society 17 (1975), S. 170-196 OBIZZI P. PETROBELLI, L’ “Ermonia“ di Pio Enea degli Obizzi ed i primi spettacoli d´opera veneziani, Quaderni della Rassegna musicale 3 (1966), S. 125-141 1643MONTEVERDI ANNA AMALIE ABERT, Claudio Monteverdi und das musikalische Drama, Lippstadt: Kistner & Siegel & Co. 1954 Claudio Monteverdi und die Folgen. Bericht über das Internationale Symposium Detmold 1993, hrsg. von SILKE LEOPOLD und JOACHIM STEINHEUER, Kassel – Basel – London – New York – Prag: Bärenreiter 1998, 497 S. Der Band gliedert sich in zwei Teile: Quellen der Monteverdi-Rezeption in Europa (8 Beiträge) sowie Monteverdi und seine Zeitgenossen (15 Beiträge); hier sollen nur jene Studien vorgestellt werden, in denen Libretto und Oper eine Rolle spielen: H. SEIFERT, Monteverdi und die Habsburger (S. 77-91) [faßt alle bekannten Fakten zusammen und fragt abschließend (S. 91) nach möglichen Einflüssen Monteverdis auf das Wiener Opernschaffen]. – A. SZWEYKOWSKA, Monteverdi in Polen (S. 93-104) [um 1600 wirken in Polen zahlreiche italienische Musiker, vor allem in der königlichen Hofkapelle; Monteverdi lernte den künftigen König Wladyslaw IV. 1625 in Venedig kennen. Marco Scacchi, der Leiter der Kapelle, deren Mitglieder auch drammi per musica komponierten (vgl. -

STILL NO REST for the REQUIEM: an ENIGMA RECONSIDERED by David Schildkret

STILL NO REST FOR THE REQUIEM: AN ENIGMA RECONSIDERED by David Schildkret (This essay was originally presented in 1993 at the University of Rochester as part of a lecture series on mysteries. It was revised and republished for a 2006 performance of the Mozart Requiem by the Mount Desert Summer Chorale.) The brothers Grimm could not have conceived a better tale than the one surrounding the composition of Mozart's Requiem. Almost immediately after the composer's death in 1791, it became known that he had been working on a Requiem Mass, and there were rumors about the curious circumstances under which he came to write it. Here are the main points of the familiar story: A mysterious stranger presented Mozart with an unsigned letter commissioning him to write a Requiem. As Mozart labored feverishly on the piece, his health declined and he became obsessed with thoughts of death. He believed that he was being poisoned and that he was writing his own funeral mass at the behest of a being from the other world, in the form of the unknown messenger. Mozart left the Requiem unfinished at his death and the task of completing it eventually fell to Mozart's pupil, Süssmayr, who is responsible for the version of the work most often performed today. This fantastic tale has been the subject of inquiry since at least 1826, when the publisher Johann André declared it a "fairy-story." The greatest mystery, the identity of the anonymous patron, was dispelled in 1964 when Otto Erich Deutsch discovered a document which conclusively proved what had been suspected for some time: Count von Walsegg, a wealthy nobleman and composer manqué, had secretly commissioned the work so that he could perform it as his own composition. -

The House Composers of the Theater Auf Der Wieden in the Time of Mozart (1789-91)1

The House Composers of the Theater auf der Wieden in the Time of Mozart (1789-91)1 DAVID J. BUCH Some of the most important theatrical music in Europe was produced at the Theater auf der Wieden in suburban Vienna in the years 1789 to 1801. Beginning with the immensely popular Die zween Anton oder der dumme Gärtner aus dem Gebirge in July 1789, Emanuel Schikaneder produced one successful singspiel after another. The most successful of these were quickly staged in other European venues, both in the original German and in translation.2 Yet, until recently, we have known only a single opera from that period, Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte. Because scholars have not studied this repertory,3 a myth of singularity for Mozart’s singspiel has dominated the secondary literature. But Mozart’s opera was in fact the fourth in a series of fairy-tale singspiels based on texts associated with Christoph Martin Wieland. And the music of Mozart’s singspiel is firmly rooted in a unique style developed at the theater by a group of talented composers who interacted with Mozart, both learning from the master and influencing him in turn. Another myth about this theater has also persisted in modern literature, namely, that the music was of an inferior quality and that the performances were rather crude. While there is one derisive review of a performance at the Theater auf der Wieden by a north German commentator in 1793,4 most contemporary reviews were positive, noting a high standard of musical performance. In his unpublished autobiography, Ignaz von Seyfried recalled performances of operas in the early 1790s by Mozart, Süßmayr, Hoffmeister etc., writing that they were performed with rare skill (ungemein artig). -

Die Zauberflöte, Masonic Opera, and Other Fairy Tales Author(S): David J

Die Zauberflöte, Masonic Opera, and Other Fairy Tales Author(s): David J. Buch Source: Acta Musicologica, [Vol.] 76, [Fasc.] 2 (2004), pp. 193-219 Published by: International Musicological Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25071239 Accessed: 11/10/2010 08:38 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=inmuso. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. International Musicological Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Acta Musicologica. http://www.jstor.org Die Zauberfl?te, Masonic Opera, and Other Fairy Tales* David J.Buch Cedar Falls, Iowa The term 'Masonic opera' isoften applied to Mozart's Die Zauberfl?te to indicate per vasive Masonic content in the form of a hidden coherent allegory with a complex representation of the order's symbols and initiation rituals. -

The Magic Flute

The Magic Flute Opera Box Table of Contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .9 Reference/Tracking Guide . .10 Lesson Plans . .13 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – a biography ......................49 Catalogue of Mozart’s Operas . .51 Background Notes . .53 Emanuel Schikaneder, Mozart and the Masons . .57 World Events in 1791 ....................................63 History of Opera ........................................66 2003 – 2004 SEASON History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .77 The Standard Repertory ...................................81 Elements of Opera .......................................82 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................86 GIUSEPPE VERDI NOVEMBER 15 – 23, 2003 Glossary of Musical Terms .................................92 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .95 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .98 GAETANO DONIZETTI JANUARY 24 – FEBRUARY 1, 2004 Evaluation . .101 Acknowledgements . .102 STEPHEN SONDHEIM FEBRUARY 28 – MARCH 6, 2004 mnopera.org WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART MAY 15 – 23, 2004 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 620 North First Street, Minneapolis, MN 55401 Kevin Ramach, PRESIDENT AND GENERAL DIRECTOR Dale Johnson, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dear Educator, Thank you for using a Minnesota Opera Opera Box. This collection of material has been designed to help any educator to teach students about the beauty of opera. This collection of material includes audio and video recordings, scores, reference books and a Teacher’s Guide. The Teacher’s Guide includes Lesson Plans that have been designed around the materials found in the box and other easily obtained items. In addition, Lesson Plans have been aligned with State and National Standards. See the Unit Overview for a detailed explanation. Before returning the box, please fill out the Evaluation Form at the end of the Teacher’s Guide. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The work of Emanuel Schikaneder and the tradition of the old Viennese popular theatre Batley, E. M. How to cite: Batley, E. M. (1965) The work of Emanuel Schikaneder and the tradition of the old Viennese popular theatre, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9998/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 120 EHIAMJEL SCHISMEDER IN VIEMA (1789-^1812) 121 MUSIC IN THE FKEaHAUSTHBATER AMD THE THEATER AN DER WIEN ERRATA p. 129.; St)r 'Two hundred' read 'two hundred', etCoo. Po 152. For *R>rty-.four* read 'forty-four*. Po 204. For 'durchgestrleljenen* read *durchgetrle'benen* 122(a) lo ESc po 72. 2,. ibido ppo 1^6-151. Das Freihaustheater. y 3o ' cf.9 pp, 57-119- 4. cfo, rjTA. 179^. p.