Three Marshalls"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Companion to the American West

A COMPANION TO THE AMERICAN WEST Edited by William Deverell A Companion to the American West BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO HISTORY This series provides sophisticated and authoritative overviews of the scholarship that has shaped our current understanding of the past. Defined by theme, period and/or region, each volume comprises between twenty- five and forty concise essays written by individual scholars within their area of specialization. The aim of each contribution is to synthesize the current state of scholarship from a variety of historical perspectives and to provide a statement on where the field is heading. The essays are written in a clear, provocative, and lively manner, designed for an international audience of scholars, students, and general readers. Published A Companion to Western Historical Thought A Companion to Gender History Edited by Lloyd Kramer and Sarah Maza Edited by Teresa Meade and Merry E. Weisner-Hanks BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO BRITISH HISTORY Published In preparation A Companion to Roman Britain A Companion to Britain in the Early Middle Ages Edited by Malcolm Todd Edited by Pauline Stafford A Companion to Britain in the Later Middle Ages A Companion to Tudor Britain Edited by S. H. Rigby Edited by Robert Tittler and Norman Jones A Companion to Stuart Britain A Companion to Nineteenth-Century Britain Edited by Barry Coward Edited by Chris Williams A Companion to Eighteenth-Century Britain A Companion to Contemporary Britain Edited by H. T. Dickinson Edited by Paul Addison and Harriet Jones A Companion to Early Twentieth-Century Britain Edited by Chris Wrigley BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO EUROPEAN HISTORY Published A Companion to Europe 1900–1945 A Companion to the Worlds of the Renaissance Edited by Gordon Martel Edited by Guido Ruggiero Planned A Companion to the Reformation World A Companion to Europe in the Middle Ages Edited by R. -

The Conflict Between the California Indian and White Civilization:Iii

I BE RO ... AM E RICA,N A: 23 THE CONFLICT BETWEEN THE CALIFORNIA INDIAN AND WHITE CIVILIZATION:III S. F. COOK -c - THE CONFLICT BETWEEN THE CALIFORNIA INDIAN AND' WHITE CIVILIZATION III. THE AMERICAN INVASION, 1848-1870 BY S. F. COOK UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND LOS ANGELES 1943 CONTENTS IBERO-AMERICANA: 23 EDITORS: C. O. SAUER, LAWRENCE KINNAIRD, L. B. SIMPSON PART THREE. THE AMERICAN INVASION, 1848-1870 II5 pages PAGE Submitted by editors February 13, 1942 Introduction. I Issued April 20, 1943 Price, $1.25 Military Casualties, 1848-1865 . Social Homicide Disease. Food and Nutrition UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND Los ANGELES Labor . CALIFORNIA Sex and Family Relations Summary and Comparisons CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON,ENGLAND APPENDIX Table 1. Indian Population from the End of the Mission Period to Modern Times . Table 2. Estimated Population in 1848, 1852, and 1880 . Koupi od ~ Table 3. Indian Losses from Military Operations, 1847- Darem od u ~:ij3.A 1865 ............... 106 V Table 4. Population Decline due to Military Casualties, 1848-1880. III IllV b Table 5. Social Homicide, 1852-1865 II2 . C' . ",I PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA The American Invasion, 1848-1870 INTRODUCTION HEN THE CALIFORNIA INDIAN was confronted with the prob lem of contact and competition with the white race, his suc W cess was much less marked with the Anglo-American than with the Ibero-American branch. To be sure, his success against the latter had been far from noteworthy; both in the missions and in the native habitat the aboriginal population'had declined, and the Indian had been forced to give ground politically and racially before the advance of Spanish colonization. -

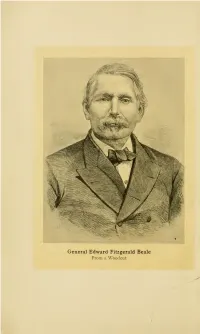

Edward Fitzgerald Beale from a Woodcut Edward Fitzgerald Beale

General Edward Fitzgerald Beale From a Woodcut Edward Fitzgerald Beale A Pioneer in the Path of Empire 1822-1903 By Stephen Bonsai With 17 Illustrations G. P. Putnam's Sons New York and London Ube ftnicfterbocfter press 1912 r6n5 Copyright, iqi2 BY TRUXTUN BEALE Ube finickerbocher pteee, 'Mew ]|?ocft £CI.A;n41 4S INTRODUCTORY NOTE EDWARD FITZGERALD BEALE, whose life is outlined in the following pages, was a remarkable man of a type we shall never see in America again. A grandson of the gallant Truxtun, Beale was bom in the Navy and his early life was passed at sea. However, he fought with the army at San Pasqual and when night fell upon that indecisive battlefield, with Kit Carson and an anonymous Indian, by a daring journey through a hostile country, he brought to Commodore Stockton in San Diego, the news of General Kearny's desperate situation. Beale brought the first gold East, and was truly, in those stirring days, what his friend and fellow- traveller Bayard Taylor called him, "a pioneer in the path of empire." Resigning from the Navy, Beale explored the desert trails and the moimtain passes which led overland to the Pacific, and later he surveyed the routes and built the wagon roads over which the mighty migration passed to people the new world beyond the Rockies. As Superintendent of the Indians, a thankless office which he filled for three years, Beale initiated a policy of honest dealing with the nation's wards iv Introductory Note which would have been even more successful than it was had cordial unfaltering support always been forthcoming from Washington. -

Or, Early Times in Southern California. by Major Horace Bell

Reminiscences of a ranger; or, Early times in southern California. By Major Horace Bell REMINISCENCES —OF A— RANGER —OR,— EARLY TIMES —IN— SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA, By MAJOR HORACE BELL. LOS ANGELES: YARNELL, CAYSTILE & MATHES, PRINTERS. 1881. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1881, by HORACE BELL, In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D.C. TO THE FEW Reminiscences of a ranger; or, Early times in southern California. By Major Horace Bell http://www.loc.gov/resource/calbk.103 SURVIVING MEMBERS OF THE LOS ANGELES RANGERS, AND TO THE MEMORY OF THOSE WHO HAVE ANSWERED TO THE LAST ROLL-CALL, THIS HUMBLE TRIBUTE IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR. PREFACE. No country or section during the first decade following the conquest of California, has been more prolific of adventure than our own bright and beautiful land; and to rescue from threatened oblivion the incidents herein related, and either occurring under the personal observation of the author, or related to him on the ground by the actors therein, and to give place on the page of history to the names of brave and worthy men who figured in the stirring events of the times referred to, as well as to portray pioneer life as it then existed, not only among the American pioneers, but also the California Spaniards, the author sends forth his book of Reminiscences, trusting that its many imperfections may be charitably scrutinized by a criticising public, and that the honesty of purpose with which it is written will be duly appreciated. H. B. -

Memorial to Charles Lewis Camp 1893-1975

Memorial to Charles Lewis Camp 1893-1975 CARL BRIGGS 376 Corral De Tierra Road, Salinas, California 93908 The bold image of Charles Camp and the record of his intense endeavors stand in clear relief on the summits of two major frontiers of study—science and history. Charles Lewis Camp was born of pioneer stock in Jamestown, North Dakota, on March 12, 1893. He spent his boyhood in southern California where he deve loped lifelong scientific interests through study with the noted naturalist Joseph Grinnell. Frequent visits to John C. Mirriam’s fossil beds at Rancho La Brea in Los Angeles further stimulated his curiosity and set the course of his career. Camp first attended Throop Academy (now Cali fornia Institute of Technology) and then followed Joseph Grinnell to the University of California at Berke ley, where he graduated in 1915 with a degree in zoology. He went on to perform graduate work at Columbia University and the American Museum of Natural History where, under the inspiration and guidance of William King Gregory and Henry Fairfield Osborn, Camp earned his master’s and doctor’s degrees. World War 1 temporarily interrupted Camp’s education. He served with distinction as a combat officer with the 7th Field Artillery, U.S. 1st Division, both as a front-line artillery spotter and a commander of troops. He received unit and individual citations for action during 1918 at Menil-la-Tour, Cantigny, Soissons, and Meuse-Argonne. From his own division commander, Camp received, under general orders, a citation as “an officer of most splendid courage and ability. -

SOME EARLY HISTORY of OWENS RIVER VALLEY Author(S): J

SOME EARLY HISTORY OF OWENS RIVER VALLEY Author(s): J. M. GUINN Source: Annual Publication of the Historical Society of Southern California, Vol. 10, No. 3 (1917), pp. 41-47 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Historical Society of Southern California Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41168743 Accessed: 23-01-2020 02:15 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Historical Society of Southern California, University of California Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Annual Publication of the Historical Society of Southern California This content downloaded from 47.157.197.123 on Thu, 23 Jan 2020 02:15:37 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms SOME EARLY HISTORY OF OWENS RIVER VALLEY BY J. M. GUINN Since its connection to Los Angeles by the Aqueduct, Owens River Valley has become almost an appendage of our city. Of the thousands of people who use the water brought two hundred miles through the Owens River Aqueduct very few know anything of the early history of the river, the valley or the lake. Who discovei-ed the valley ? who named the lake and the river ? and for whom were they named ? are questions that would puzzle many of our local his- torians and confound the mass of its water users. -

California Landmarks

Original Historical Landmarks Index to Books I, II and III Plaques Dedicated by Grand Parlor, Parlors, or Parlors with Other Groups September 2009 Native Daughters of the Golden West 543 Baker Street San Francisco, California 94117-1405 Monument Vol 1-3.doc, September 17, 2009 Index to Original Historical Landmarks, Books I, II and III Page 2 of 38 Dedications with Native Sons of the Golden West are indicated by “+” Dedications with Other Groups are indicated by “++” County Plaque Dedicated Parlor Location Description Bk/Pge Goal 1/001 Dedication 1/003 Presentation 1/005 Sponsor 1/009 Founder, Lilly Dyer 1/013 State Information Name, Motto, etc. 1/014 Thirty First Star 1/017 1/020 Flags of California 1/021 State Seal 1/027 Mothers Day May 9, 1971 Grin and Bear It Cartoon 1/029 N. D. G. W. Directory 1/031 Landmarks Title Page 1/035 Historic California Missions 1965 Pamphlet 1/047 1/051 Mission Soledad 1/052 Mission Nuestra Senora County Road, Mission 1/053 Restored mission, Registered Dolorosisima De La Oct 14, 1956 NDGW Grand Parlor District, Soledad, Monterey 1/054 Landmark No. 233 Soledad Co. 1/055 Mission Picture 1/057 Subordinate Parlor Title Page 1/061 Landmarks Alameda * Parlor Listing Title Page 1/065 Church of St. James the Foothill Blvd and 12th Founded June 27,1858 by first 1/066 Alameda Dec 6, 1959 Fruitvale No. 177, ++ Apostle Ave., E. Oakland Episcopal Bishop of California 1/067 Berkeley No. 150, Bear Flag No. 151, Sequoia No. 1302-1304 Abina Street, 1841 – site of first dwelling in Alameda Domingo Peralta Adobe Mar 22, 1970 1/069 272, Albany No. -

Bent's Fort Gathers Wagons on May 11-13

Santa Fe Trail Association Quarterly volume 26 ▪ number 3 May 2012 Rendezvous 2012 Slated for September 20-22 SFTA News “Santa Fe Trail Characters – Rendezvous on the Road” Wagons Ho! Bent’s Fort . .1 Rendezvous 2012 . 1, 11 President’s Column . 2 The schedule for Rendezvous 2012, Manager’s Column. 3 September 20-22 in Larned, Kansas, has been announced. The full schedule is on News . 4 - 5 page 11 of this issue. PNTS . 4 In Memoriam. .25 Characters who will be portrayed in the Chapter Reports . 25 first person include William Becknell, Membership Renewal . 27 Julia Archibald Holmes, Pedro Sando- Events . 28 val, Frederick Hawn, Deputy Surveyor for the General Land Office, Kit Carson, Marion Sloan Russell, Alexander Majors, James Kirker, Maria de la Luz Articles Beaubien Maxwell, and J. B. Kickok. Dearborn Wagons: Holt . 6 Further details and a registration Hansen Wheel and Wagon packet will follow in the August is- Shop: Hansen. .7 sue of Wagon Tracks. The Santa Fe Santa Fe Freighters: Sneed . .9 Trail Center will also send out a direct Diary of Levi Edmonds, Sr.: mailing to Santa Fe Trail Association White and Rogers . 13 members closer to the time of the event. Images of SW Colorado: For questions or further information you can contact the Santa Fe Trail Center at David Sandoval as Pedro Sandoval Campbell. 20 620-285-2054. Columns Bent’s Fort Gathers Wagons on May 11-13 Young People on the Don’t miss the wagon extravaganza, “Wagons Ho! Trail Transportation through Time” Trail: Junior Wagon Mas- at Bent’s Fort, Colorado on the second weekend in May. -

Biography Denver General Subject Railroads States and Cities Misc

Biography Denver General Subject Railroads States and Cities Misc. Visual Materials BIOGRAPHY A Abeyta family Abbott, Emma Abbott, Hellen Abbott, Stephen S. Abernathy, Ralph (Rev.) Abot, Bessie SEE: Oversize photographs Abreu, Charles Acheson, Dean Gooderham Acker, Henry L. Adair, Alexander Adami, Charles and family Adams, Alva (Gov.) Adams, Alva Blanchard (Sen.) Adams, Alva Blanchard (Sen.) (Adams, Elizabeth Matty) Adams, Alva Blanchard Jr. Adams, Andy Adams, Charles Adams, Charles Partridge Adams, Frederick Atherton and family Adams, George H. Adams, James Capen (“Grizzly”) Adams, James H. and family Adams, John T. Adams, Johnnie Adams, Jose Pierre Adams, Louise T. Adams, Mary Adams, Matt Adams, Robert Perry Adams, Mrs. Roy (“Brownie”) Adams, W. H. SEE ALSO: Oversize photographs Adams, William Herbert and family Addington, March and family Adelman, Andrew Adler, Harry Adriance, Jacob (Rev. Dr.) and family Ady, George Affolter, Frederick SEE ALSO: oversize Aichelman, Frank and Agnew, Spiro T. family Aicher, Cornelius and family Aiken, John W. Aitken, Leonard L. Akeroyd, Richard G. Jr. Alberghetti, Carla Albert, John David (“Uncle Johnnie”) Albi, Charles and family Albi, Rudolph (Dr.) Alda, Frances Aldrich, Asa H. Alexander, D. M. Alexander, Sam (Manitoba Sam) Alexis, Alexandrovitch (Grand Duke of Russia) Alford, Nathaniel C. Alio, Giusseppi Allam, James M. Allegretto, Michael Allen, Alonzo Allen, Austin (Dr.) Allen, B. F. (Lt.) Allen, Charles B. Allen, Charles L. Allen, David Allen, George W. Allen, George W. Jr. Allen, Gracie Allen, Henry (Guide in Middle Park-Not the Henry Allen of Early Denver) Allen, John Thomas Sr. Allen, Jules Verne Allen, Orrin (Brick) Allen, Rex Allen, Viola Allen William T. -

Four Engineers on the Missouri: Long, Fremont, Humphreys, and Warren

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Four Engineers on the Missouri: Long, Fremont, Humphreys, and Warren Full Citation: Lawrence C Allin, “Four Engineers on the Missouri: Long, Fremont, Humphreys, and Warren,” Nebraska History 65 (1984): 58-83 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1984Engineers.pdf Date: 12/16/2013 Article Summary: Engineers brought scientific method to the examination of the Missouri River Basin. They found a railroad route into the west and helped open the continent. Cataloging Information: Names: Stephen H Long, John Charles (“Pathfinder”) Fremont, Jessie Benton Fremont, Andrew A Humphreys, Gouverneur Kemble Warren, Henry Atkinson, John R Bell, Joseph Nicolas Nicollet, Charles Geyer, Thomas Hart Benton, Peter A Sarpy, Jim Bridger, Charles Preuss, William H Emory, Jefferson Davis, Stephen A Douglas, John W Gunnison, Edward G Beckwith, Edwin James, Samuel -

South Dakota History

VOL. 41, NO. 1 SPRING 2011 South Dakota History 1 Index to South Dakota History, Volumes 1–40 (1970–2010) COMPILED BY RODGER HARTLEY Copyright 2011 by the South Dakota State Historical Society, Pierre, S.Dak. 57501-2217 ISSN 0361-8676 USER’S GUIDE Over the past forty years, each volume (four issues) of South Dakota History has carried its own index. From 1970 to 1994, these indexes were printed separately upon comple- tion of the last issue for the year. If not bound with the volume, as in a library set, they were easily misplaced or lost. As the journal approached its twenty-fifth year of publica- tion, the editors decided to integrate future indexes into the back of every final issue for the volume, a practice that began with Volume 26. To mark the milestone anniversary in 1995, they combined the indexes produced up until that time to create a twenty-five-year cumulative index. As the journal’s fortieth anniversary year of 2010 approached, the need for another compilation became clear. The index presented here integrates the past fifteen volume indexes into the earlier twenty-five-year cumulative index. While indexers’ styles and skills have varied over the years, every effort has been made to create a product that is as complete and consistent as possible. Throughout the index, volume numbers appear in bold-face type, while page numbers are in book-face. Within the larger entries, references to brief or isolated pas- sages are listed at the beginning, while more extensive references are grouped under the subheadings that follow. -

The Grapevine Route the Mexican-American War of 1846

The Grapevine Route The Mexican-American war of 1846 marked the abandonment of the El Camino Viejo route in favor of the Grapevine Route as it was a shorter route. Plus, the San Emigdio Land Grant owners had created a working cattle ranch, and discouraged travel passing through their rancho. This rancho has been under ownership of many different people, including John C. Fremont and his partner, Edward Beale, both heroes of the Mexican-American war. Alexis Godey became the overseer of the rancho, who has a “legend” ranging from being a benefactor to the natives to being a murderer of the natives. (Currently, this rancho area is under the care of the Wind Wolves Preserve. Naturalists lead a 10-mile hike following the historic El Camino Viejo (hiking down from Pine Mt. Club to Preserve). The history of the development of the Grapevine Route cannot be discussed without mention of Edward Fitzgerald Beale. His impact upon the growth and settlement of this area, to his death in 1983, cannot be separated out from the local history. Beale arrived in California in 1846, as a Naval Officer serving under Colonel John C. Fremont during the Mexican war. Beale played a significant role in the lives of the local Indians. While the history of the Federal- Indian relationship in California shares some common characteristics with that of Native people elsewhere in the United States, it is different in many aspects. This difference is important to understanding many of the current issues in the mountains as to how the tribes have been affected.