SOME EARLY HISTORY of OWENS RIVER VALLEY Author(S): J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Sacramento District 1325 J Street Sacramento, California Contract: DACA05-97-D-0013, Task 0001 FOSTER WHEELER ENVIRONMENTAL CORPORATION

CALIFORNIA HISTORIC MILITARY BUILDINGS AND STRUCTURES INVENTORY VOLUME II: THE HISTORY AND HISTORIC RESOURCES OF THE MILITARY IN CALIFORNIA, 1769-1989 by Stephen D. Mikesell Prepared for: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Sacramento District 1325 J Street Sacramento, California Contract: DACA05-97-D-0013, Task 0001 FOSTER WHEELER ENVIRONMENTAL CORPORATION Prepared by: JRP JRP HISTORICAL CONSULTING SERVICES Davis, California 95616 March 2000 California llistoric Military Buildings and Stnictures Inventory, Volume II CONTENTS CONTENTS ..................................................................................................................................... i FIGURES ....................................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF ACRONYMS .................................................................................................................. iv PREFACE .................................................................................................................................... viii 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1-1 2.0 COLONIAL ERA (1769-1846) .............................................................................................. 2-1 2.1 Spanish-Mexican Era Buildings Owned by the Military ............................................... 2-8 2.2 Conclusions .................................................................................................................. -

California State Parks

1 · 2 · 3 · 4 · 5 · 6 · 7 · 8 · 9 · 10 · 11 · 12 · 13 · 14 · 15 · 16 · 17 · 18 · 19 · 20 · 21 Pelican SB Designated Wildlife/Nature Viewing Designated Wildlife/Nature Viewing Visit Historical/Cultural Sites Visit Historical/Cultural Sites Smith River Off Highway Vehicle Use Off Highway Vehicle Use Equestrian Camp Site(s) Non-Motorized Boating Equestrian Camp Site(s) Non-Motorized Boating ( Tolowa Dunes SP C Educational Programs Educational Programs Wind Surfing/Surfing Wind Surfing/Surfing lo RV Sites w/Hookups RV Sites w/Hookups Gasquet 199 s Marina/Boat Ramp Motorized Boating Marina/Boat Ramp Motorized Boating A 101 ed Horseback Riding Horseback Riding Lake Earl RV Dump Station Mountain Biking RV Dump Station Mountain Biking r i S v e n m i t h R i Rustic Cabins Rustic Cabins w Visitor Center Food Service Visitor Center Food Service Camp Site(s) Snow Sports Camp Site(s) Geocaching Snow Sports Crescent City i Picnic Area Camp Store Geocaching Picnic Area Camp Store Jedediah Smith Redwoods n Restrooms RV Access Swimming Restrooms RV Access Swimming t Hilt S r e Seiad ShowersMuseum ShowersMuseum e r California Lodging California Lodging SP v ) l Klamath Iron Fishing Fishing F i i Horse Beach Hiking Beach Hiking o a Valley Gate r R r River k T Happy Creek Res. Copco Del Norte Coast Redwoods SP h r t i t e s Lake State Parks State Parks · S m Camp v e 96 i r Hornbrook R C h c Meiss Dorris PARKS FACILITIES ACTIVITIES PARKS FACILITIES ACTIVITIES t i Scott Bar f OREGON i Requa a Lake Tulelake c Admiral William Standley SRA, G2 • • (707) 247-3318 Indian Grinding Rock SHP, K7 • • • • • • • • • • • (209) 296-7488 Klamath m a P Lower CALIFORNIA Redwood K l a Yreka 5 Tule Ahjumawi Lava Springs SP, D7 • • • • • • • • • (530) 335-2777 Jack London SHP, J2 • • • • • • • • • • • • (707) 938-5216 l K Sc Macdoel Klamath a o tt Montague Lake A I m R National iv Lake Albany SMR, K3 • • • • • • (888) 327-2757 Jedediah Smith Redwoods SP, A2 • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • (707) 458-3018 e S Mount a r Park h I4 E2 t 3 Newell Anderson Marsh SHP, • • • • • • (707) 994-0688 John B. -

Chapter 8 Manzanar

CHAPTER 8 MANZANAR Introduction The Manzanar Relocation Center, initially referred to as the “Owens Valley Reception Center”, was located at about 36oo44' N latitude and 118 09'W longitude, and at about 3,900 feet elevation in east-central California’s Inyo County (Figure 8.1). Independence lay about six miles north and Lone Pine approximately ten miles south along U.S. highway 395. Los Angeles is about 225 miles to the south and Las Vegas approximately 230 miles to the southeast. The relocation center was named after Manzanar, a turn-of-the-century fruit town at the site that disappeared after the City of Los Angeles purchased its land and water. The Los Angeles Aqueduct lies about a mile to the east. The Works Progress Administration (1939, p. 517-518), on the eve of World War II, described this area as: This section of US 395 penetrates a land of contrasts–cool crests and burning lowlands, fertile agricultural regions and untamed deserts. It is a land where Indians made a last stand against the invading white man, where bandits sought refuge from early vigilante retribution; a land of fortunes–past and present–in gold, silver, tungsten, marble, soda, and borax; and a land esteemed by sportsmen because of scores of lakes and streams abounding with trout and forests alive with game. The highway follows the irregular base of the towering Sierra Nevada, past the highest peak in any of the States–Mount Whitney–at the western approach to Death Valley, the Nation’s lowest, and hottest, area. The following pages address: 1) the physical and human setting in which Manzanar was located; 2) why east central California was selected for a relocation center; 3) the structural layout of Manzanar; 4) the origins of Manzanar’s evacuees; 5) how Manzanar’s evacuees interacted with the physical and human environments of east central California; 6) relocation patterns of Manzanar’s evacuees; 7) the fate of Manzanar after closing; and 8) the impact of Manzanar on east central California some 60 years after closing. -

The 2014 Regional Transportation Plan Promotes a More Efficient

CHAPTER 5 STRATEGIC INVESTMENTS – VERSION 5 CHAPTER 5 STRATEGIC INVESTMENTS INTRODUCTION This chapter sets forth plans of action for the region to pursue and meet identified transportation needs and issues. Planned investments are consistent with the goals and policies of the plan, the Sustainable Community Strategy element (see chapter 4) and must be financially constrained. These projects are listed in the Constrained Program of Projects (Table 5-1) and are modeled in the Air Quality Conformity Analysis. The 2014 Regional Transportation Plan promotes Forecast modeling methods in this Regional Transportation a more efficient transportation Plan primarily use the “market-based approach” based on demographic data and economic trends (see chapter 3). The system that calls for fully forecast modeling was used to analyze the strategic funding alternative investments in the combined action elements found in this transportation modes, while chapter.. emphasizing transportation demand and transporation Alternative scenarios are not addressed in this document; they are, however, addressed and analyzed for their system management feasibility and impacts in the Environmental Impact Report approaches for new highway prepared for the 2014 Regional Transportation Plan, as capacity. required by the California Environmental Quality Act (State CEQA Guidelines Sections 15126(f) and 15126.6(a)). From this point, the alternatives have been predetermined and projects that would deliver the most benefit were selected. The 2014 Regional Transportation Plan promotes a more efficient transportation system that calls for fully funding alternative transportation modes, while emphasizing transportation demand and transporation system management approaches for new highway capacity. The Constrained Program of Projects (Table 5-1) includes projects that move the region toward a financially constrained and balanced system. -

Reports of the Great California Earthquake of 1857

REPORTS OF THE GREAT CALIFORNIA EARTHQUAKE OF 1857 REPRINTED AND EDITED WITH EXPLANATORY NOTES VERSION 1.01 DUNCAN CARR AGNEW INSTITUTE OF GEOPHYSICS AND PLANETARY PHYSICS SCRIPPS INSTITUTION OF OCEANOGRAPHY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LA JOLLA CALIFORNIA 2006 Abstract This publication reprints 77 primary accounts that describe the effects of the “Fort Tejon” earthquake of January 9, 1857, which was caused by the rupture of the San Andreas Fault from Parkfield to San Bernardino. These accounts include 70 contemporary documents (52 newspaper reports, 17 letters and journals, and one scientific paper) and seven reminiscences, which describe foreshocks, felt effects, faulting, and some of the aftershocks associated with this earthquake. Most of the reports come from the major populated areas: Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, Santa Cruz, San Jose, Sacramento, and Stockton, but other areas are also covered. Notes on toponomy and other historical issues are included. These documents were originally published as a microfiche supplement to Agnew and Sieh (1978); this reprinting is intended to make them more widely accessible on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of this earthquake. 1 Introduction The collection of earthquake reports reprinted here began in 1972, as a project for a class on seismology taught by Clarence Allen, in which I learned that the southern extent of faulting in the 1857 “Fort Tejon” earthquake was uncertain. From reading Arrington (1958) in a previous course in Western US history, I knew that there had been a Mormon colony in San Bernardino in 1857, and that most colonies kept a daily journal. A trip to the Church Historical Office in Salt Lake City found such a journal, and a search through available newspapers showed many more accounts than had been used by Wood (1955). -

Cajon Pass As You've Never Seen It

MAP OF THE MONTH Cajon Pass as you’ve never seen it Your all-time guide to the busiest railroad mountain crossing in the United States. We map 126 years of railroad history “HILL 582” CP SP462 Popular railfan CP SP465 HILAND Alray INTERSTATE hangout SILVERWOOD Former passing 15 66 siding removed 1972, Original 1885 line through To Palmdale named for track Main 1 Setout siding Summit relocated 1972; the Setout siding supervisor Al Ray new line reduced the summit Main 3 3N45 elevation by 50 feet. “STEIN’S HILL” Tunnel No. 1 SILVERWOOD Named for noted Eliminated 2008 Main 2 MP 56.6 ific CP SP464 Pac rail photographer Tunnel No. 2 3N48 Union Richard Steinheimer. Eliminated 2008 Parker Dell Ranch To Barstow Rd. 138 BNSF WALKER Summit Road MP 59.4 Named for longtime 138 Summit operator and Gish author Chard Walker Original 1885 line; Summit SUMMIT Warning: became passing Site of depot and MP 55.9 The tracks east of the Summit siding 1920s; helper turning wye Road crossing are in the BNSF 1913 line removed 1956 security area, established 1996. relocated 1977 It is lit, fenced, and guarded. Do not trespass in this area. OLD TRAILS HIGHWAY First paved road over Cajon Exit 131 Pass 1916, first route for Route PACIFIC CRESTFUN HIKING FACT TRAIL Route 138 66; originally a 12-mile toll road The Pacific Crest Hiking Trail runs opened in 1861, now a trail. 2,638 miles from Canada to Mexico. 138 Rim of the World Scenic Byway Lone Pine Canyon Rd. DESCANSO MORMON ROCKS CP SP464 is the approximate SAN BERNARDINO NATIONAL FOREST Named for a party location of the Los Angeles Rwy. -

SJV Interregional Goods Movement Study

San Joaquin Valley Interregional Goods Movement Plan Task 9: Final Report Prepared for San Joaquin Valley Regional Transportation Planning Agencies Prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. with The Tioga Group, Inc. Fehr & Peers Jock O’Connell Date: August 2013 Task 9: Final Report prepared for San Joaquin Valley Governments Regional Transportation Planning Agencies prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. 555 12th Street, Suite 1600 Oakland, CA 94607 date August 2013 San Joaquin Valley Goods Movement Plan Task 9: Final Report Table of Contents 1.0 Purpose and Scope .............................................................................................. 1-1 1.1 Study Background and Purpose ............................................................... 1-1 1.2 Need for Goods Movement Planning ...................................................... 1-2 1.3 Study Scope and Approach ....................................................................... 1-3 2.0 SJV Goods Movement ....................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 Importance of Goods Movement .............................................................. 2-1 2.2 SJV Goods Movement Infrastructure ....................................................... 2-6 2.3 SJV Goods Movement Demand .............................................................. 2-15 2.4 Expected Goods Movement Growth ..................................................... 2-20 2.5 Goods Movement Issues and Challenges ............................................ -

A Companion to the American West

A COMPANION TO THE AMERICAN WEST Edited by William Deverell A Companion to the American West BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO HISTORY This series provides sophisticated and authoritative overviews of the scholarship that has shaped our current understanding of the past. Defined by theme, period and/or region, each volume comprises between twenty- five and forty concise essays written by individual scholars within their area of specialization. The aim of each contribution is to synthesize the current state of scholarship from a variety of historical perspectives and to provide a statement on where the field is heading. The essays are written in a clear, provocative, and lively manner, designed for an international audience of scholars, students, and general readers. Published A Companion to Western Historical Thought A Companion to Gender History Edited by Lloyd Kramer and Sarah Maza Edited by Teresa Meade and Merry E. Weisner-Hanks BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO BRITISH HISTORY Published In preparation A Companion to Roman Britain A Companion to Britain in the Early Middle Ages Edited by Malcolm Todd Edited by Pauline Stafford A Companion to Britain in the Later Middle Ages A Companion to Tudor Britain Edited by S. H. Rigby Edited by Robert Tittler and Norman Jones A Companion to Stuart Britain A Companion to Nineteenth-Century Britain Edited by Barry Coward Edited by Chris Williams A Companion to Eighteenth-Century Britain A Companion to Contemporary Britain Edited by H. T. Dickinson Edited by Paul Addison and Harriet Jones A Companion to Early Twentieth-Century Britain Edited by Chris Wrigley BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO EUROPEAN HISTORY Published A Companion to Europe 1900–1945 A Companion to the Worlds of the Renaissance Edited by Gordon Martel Edited by Guido Ruggiero Planned A Companion to the Reformation World A Companion to Europe in the Middle Ages Edited by R. -

The Conflict Between the California Indian and White Civilization:Iii

I BE RO ... AM E RICA,N A: 23 THE CONFLICT BETWEEN THE CALIFORNIA INDIAN AND WHITE CIVILIZATION:III S. F. COOK -c - THE CONFLICT BETWEEN THE CALIFORNIA INDIAN AND' WHITE CIVILIZATION III. THE AMERICAN INVASION, 1848-1870 BY S. F. COOK UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND LOS ANGELES 1943 CONTENTS IBERO-AMERICANA: 23 EDITORS: C. O. SAUER, LAWRENCE KINNAIRD, L. B. SIMPSON PART THREE. THE AMERICAN INVASION, 1848-1870 II5 pages PAGE Submitted by editors February 13, 1942 Introduction. I Issued April 20, 1943 Price, $1.25 Military Casualties, 1848-1865 . Social Homicide Disease. Food and Nutrition UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND Los ANGELES Labor . CALIFORNIA Sex and Family Relations Summary and Comparisons CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON,ENGLAND APPENDIX Table 1. Indian Population from the End of the Mission Period to Modern Times . Table 2. Estimated Population in 1848, 1852, and 1880 . Koupi od ~ Table 3. Indian Losses from Military Operations, 1847- Darem od u ~:ij3.A 1865 ............... 106 V Table 4. Population Decline due to Military Casualties, 1848-1880. III IllV b Table 5. Social Homicide, 1852-1865 II2 . C' . ",I PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA The American Invasion, 1848-1870 INTRODUCTION HEN THE CALIFORNIA INDIAN was confronted with the prob lem of contact and competition with the white race, his suc W cess was much less marked with the Anglo-American than with the Ibero-American branch. To be sure, his success against the latter had been far from noteworthy; both in the missions and in the native habitat the aboriginal population'had declined, and the Indian had been forced to give ground politically and racially before the advance of Spanish colonization. -

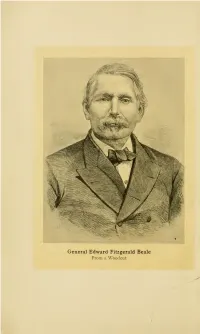

Edward Fitzgerald Beale from a Woodcut Edward Fitzgerald Beale

General Edward Fitzgerald Beale From a Woodcut Edward Fitzgerald Beale A Pioneer in the Path of Empire 1822-1903 By Stephen Bonsai With 17 Illustrations G. P. Putnam's Sons New York and London Ube ftnicfterbocfter press 1912 r6n5 Copyright, iqi2 BY TRUXTUN BEALE Ube finickerbocher pteee, 'Mew ]|?ocft £CI.A;n41 4S INTRODUCTORY NOTE EDWARD FITZGERALD BEALE, whose life is outlined in the following pages, was a remarkable man of a type we shall never see in America again. A grandson of the gallant Truxtun, Beale was bom in the Navy and his early life was passed at sea. However, he fought with the army at San Pasqual and when night fell upon that indecisive battlefield, with Kit Carson and an anonymous Indian, by a daring journey through a hostile country, he brought to Commodore Stockton in San Diego, the news of General Kearny's desperate situation. Beale brought the first gold East, and was truly, in those stirring days, what his friend and fellow- traveller Bayard Taylor called him, "a pioneer in the path of empire." Resigning from the Navy, Beale explored the desert trails and the moimtain passes which led overland to the Pacific, and later he surveyed the routes and built the wagon roads over which the mighty migration passed to people the new world beyond the Rockies. As Superintendent of the Indians, a thankless office which he filled for three years, Beale initiated a policy of honest dealing with the nation's wards iv Introductory Note which would have been even more successful than it was had cordial unfaltering support always been forthcoming from Washington. -

Cultural Resources

Draft DRECP and EIR/EIS CHAPTER III.8. CULTURAL RESOURCES III.8 CULTURAL RESOURCES This chapter presents the environmental setting/affected environment for the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan (DRECP) for cultural resources. More than 32,000 cultural resources are known in the Plan Area and occur in every existing environmental context, from mountain crests to dry lake beds, and include both surface and sub-surface deposits. Cultural resources are categorized as buildings, sites, structures, objects, and districts under both federal law (for the purposes of the National Environmental Policy Act [NEPA] and the National Historic Preservation Act [NHPA]) and under California state law (for the purposes of the California Environmental Quality Act [CEQA]). Historic properties are cultural resources included in, or eligible for inclusion in, the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) maintained by the Secretary of the Interior and per the NRHP eligibility criteria (36 Code of Federal Regulations [CFR] 60.4). See Section III.8.1.1 for more information on federal regulations and historic properties. Historical resources are cultural resources that meet the criteria for listing on the California Register of Historical Resources (CRHR) (14 California Code of Regulations [CCR] Section 4850) or that meet other criteria specified in CEQA (see Section III.8.1.2). See Section III.8.1.2 for more information on state regulations and historical resources. This chapter discusses three types of cultural resources classified by their origins: prehistoric, ethnographic, and historic. Prehistoric cultural resources are associated with the human occupation and use of Cali- fornia prior to prolonged European contact. -

Inside Historic Kern-Ch.6-Walker Basin-177-185

Little Mountain Valley Through the Years . Little Has Changed Walker Basin by Eugene Burmeister Little is known about the early history of Walker Basin. No records are found to tell who first looked down into the rich valley from the surrounding ridges, and few Indians remained there when the first white settlers arrived in 1857. The Kawaiisu of Shoshonean origin and also known as the Plateaus, Paiutes, and Tehachapis had a village in the valley. There they found an early paradise, for the basin had plentiful game, good groves of trees for camping, small lakes and a fine stream for water and fish, and rugged mountains ofering protection from enemies. The earliest known pathfinder to the area was Joseph Reddeford Walker, who discovered Walker pass in 1834 on his route east out of the San Joaquin Valley and for whom the pass a few miles northeast of there is named. The basin also got its name from this early explorer as did the famous Joe Walker Mine. The earliest settlers in Walker Basin were stockmen and farmers, enticed to the valley by its good grass, rich soil, adequate water, and ideal climate. The first to settle there was Charles H. Weick in 1857. A native of Germany, Weick raised a few cattle and farmed at the west end of the basin. After his death January 8, 1873, at the age of fifty, he was buried at his request on a little mound on his ranch. Weick was followed the next year by the John Becks, the Bob Wilsons, the Blackburns, and three bachelors, William Weldon, Joseph V.