Memorial to Charles Lewis Camp 1893-1975

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fine Americana Travel & Exploration with Ephemera & Manuscript Material

Sale 484 Thursday, July 19, 2012 11:00 AM Fine Americana Travel & Exploration With Ephemera & Manuscript Material Auction Preview Tuesday July 17, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wednesday, July 18, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Thursday, July 19, 9:00 am to 11:00 am Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor:San Francisco, CA 94108 phone: 415.989.2665 toll free: 1.866.999.7224 fax: 415.989.1664 [email protected]:www.pbagalleries.com REAL-TIME BIDDING AVAILABLE PBA Galleries features Real-Time Bidding for its live auctions. This feature allows Internet Users to bid on items instantaneously, as though they were in the room with the auctioneer. If it is an auction day, you may view the Real-Time Bidder at http://www.pbagalleries.com/realtimebidder/ . Instructions for its use can be found by following the link at the top of the Real-Time Bidder page. Please note: you will need to be logged in and have a credit card registered with PBA Galleries to access the Real-Time Bidder area. In addition, we continue to provide provisions for Absentee Bidding by email, fax, regular mail, and telephone prior to the auction, as well as live phone bidding during the auction. Please contact PBA Galleries for more information. IMAGES AT WWW.PBAGALLERIES.COM All the items in this catalogue are pictured in the online version of the catalogue at www.pbagalleries. com. Go to Live Auctions, click Browse Catalogues, then click on the link to the Sale. CONSIGN TO PBA GALLERIES PBA is always happy to discuss consignments of books, maps, photographs, graphics, autographs and related material. -

Bartolomé De Las Casas, Soldiers of Fortune, And

HONOR AND CARITAS: BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS, SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE, AND THE CONQUEST OF THE AMERICAS Dissertation Submitted To The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Damian Matthew Costello UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio August 2013 HONOR AND CARITAS: BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS, SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE, AND THE CONQUEST OF THE AMERICAS Name: Costello, Damian Matthew APPROVED BY: ____________________________ Dr. William L. Portier, Ph.D. Committee Chair ____________________________ Dr. Sandra Yocum, Ph.D. Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Kelly S. Johnson, Ph.D. Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Anthony B. Smith, Ph.D. Committee Member _____________________________ Dr. Roberto S. Goizueta, Ph.D. Committee Member ii ABSTRACT HONOR AND CARITAS: BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS, SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE, AND THE CONQUEST OF THE AMERICAS Name: Costello, Damian Matthew University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. William L. Portier This dissertation - a postcolonial re-examination of Bartolomé de las Casas, the 16th century Spanish priest often called “The Protector of the Indians” - is a conversation between three primary components: a biography of Las Casas, an interdisciplinary history of the conquest of the Americas and early Latin America, and an analysis of the Spanish debate over the morality of Spanish colonialism. The work adds two new theses to the scholarship of Las Casas: a reassessment of the process of Spanish expansion and the nature of Las Casas’s opposition to it. The first thesis challenges the dominant paradigm of 16th century Spanish colonialism, which tends to explain conquest as the result of perceived religious and racial difference; that is, Spanish conquistadors turned to military force as a means of imposing Spanish civilization and Christianity on heathen Indians. -

Ruth Frey Axe Collection of Material About H.H. Bancroft and Company, 1854-1977

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt8t1nd15t No online items Finding Aid for the Ruth Frey Axe Collection of material about H.H. Bancroft and Company, 1854-1977 Processed by UCLA Library Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections UCLA Library Special Collections staff Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2005 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. 1427 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Ruth Frey Axe Collection of material about H.H. Bancroft and Company Date (inclusive): 1854-1977 Collection number: 1427 Creator: Axe, Ruth Frey. Extent: 8 boxes (4.0 linear ft.) Abstract: Collection consists of correspondence, manuscripts, publications, and ephemera by and about H.H. Bancroft and Co. and A.L. Bancroft and Co. Ruth Frey Axe compiled the collection to complete the Bancroft publications checklist started by Henry Wagner and Eleanor Bancroft. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

A Companion to the American West

A COMPANION TO THE AMERICAN WEST Edited by William Deverell A Companion to the American West BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO HISTORY This series provides sophisticated and authoritative overviews of the scholarship that has shaped our current understanding of the past. Defined by theme, period and/or region, each volume comprises between twenty- five and forty concise essays written by individual scholars within their area of specialization. The aim of each contribution is to synthesize the current state of scholarship from a variety of historical perspectives and to provide a statement on where the field is heading. The essays are written in a clear, provocative, and lively manner, designed for an international audience of scholars, students, and general readers. Published A Companion to Western Historical Thought A Companion to Gender History Edited by Lloyd Kramer and Sarah Maza Edited by Teresa Meade and Merry E. Weisner-Hanks BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO BRITISH HISTORY Published In preparation A Companion to Roman Britain A Companion to Britain in the Early Middle Ages Edited by Malcolm Todd Edited by Pauline Stafford A Companion to Britain in the Later Middle Ages A Companion to Tudor Britain Edited by S. H. Rigby Edited by Robert Tittler and Norman Jones A Companion to Stuart Britain A Companion to Nineteenth-Century Britain Edited by Barry Coward Edited by Chris Williams A Companion to Eighteenth-Century Britain A Companion to Contemporary Britain Edited by H. T. Dickinson Edited by Paul Addison and Harriet Jones A Companion to Early Twentieth-Century Britain Edited by Chris Wrigley BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO EUROPEAN HISTORY Published A Companion to Europe 1900–1945 A Companion to the Worlds of the Renaissance Edited by Gordon Martel Edited by Guido Ruggiero Planned A Companion to the Reformation World A Companion to Europe in the Middle Ages Edited by R. -

The Conflict Between the California Indian and White Civilization:Iii

I BE RO ... AM E RICA,N A: 23 THE CONFLICT BETWEEN THE CALIFORNIA INDIAN AND WHITE CIVILIZATION:III S. F. COOK -c - THE CONFLICT BETWEEN THE CALIFORNIA INDIAN AND' WHITE CIVILIZATION III. THE AMERICAN INVASION, 1848-1870 BY S. F. COOK UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND LOS ANGELES 1943 CONTENTS IBERO-AMERICANA: 23 EDITORS: C. O. SAUER, LAWRENCE KINNAIRD, L. B. SIMPSON PART THREE. THE AMERICAN INVASION, 1848-1870 II5 pages PAGE Submitted by editors February 13, 1942 Introduction. I Issued April 20, 1943 Price, $1.25 Military Casualties, 1848-1865 . Social Homicide Disease. Food and Nutrition UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND Los ANGELES Labor . CALIFORNIA Sex and Family Relations Summary and Comparisons CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON,ENGLAND APPENDIX Table 1. Indian Population from the End of the Mission Period to Modern Times . Table 2. Estimated Population in 1848, 1852, and 1880 . Koupi od ~ Table 3. Indian Losses from Military Operations, 1847- Darem od u ~:ij3.A 1865 ............... 106 V Table 4. Population Decline due to Military Casualties, 1848-1880. III IllV b Table 5. Social Homicide, 1852-1865 II2 . C' . ",I PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA The American Invasion, 1848-1870 INTRODUCTION HEN THE CALIFORNIA INDIAN was confronted with the prob lem of contact and competition with the white race, his suc W cess was much less marked with the Anglo-American than with the Ibero-American branch. To be sure, his success against the latter had been far from noteworthy; both in the missions and in the native habitat the aboriginal population'had declined, and the Indian had been forced to give ground politically and racially before the advance of Spanish colonization. -

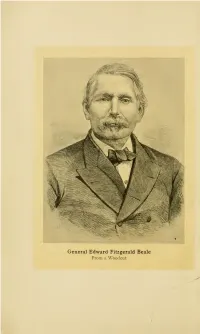

Edward Fitzgerald Beale from a Woodcut Edward Fitzgerald Beale

General Edward Fitzgerald Beale From a Woodcut Edward Fitzgerald Beale A Pioneer in the Path of Empire 1822-1903 By Stephen Bonsai With 17 Illustrations G. P. Putnam's Sons New York and London Ube ftnicfterbocfter press 1912 r6n5 Copyright, iqi2 BY TRUXTUN BEALE Ube finickerbocher pteee, 'Mew ]|?ocft £CI.A;n41 4S INTRODUCTORY NOTE EDWARD FITZGERALD BEALE, whose life is outlined in the following pages, was a remarkable man of a type we shall never see in America again. A grandson of the gallant Truxtun, Beale was bom in the Navy and his early life was passed at sea. However, he fought with the army at San Pasqual and when night fell upon that indecisive battlefield, with Kit Carson and an anonymous Indian, by a daring journey through a hostile country, he brought to Commodore Stockton in San Diego, the news of General Kearny's desperate situation. Beale brought the first gold East, and was truly, in those stirring days, what his friend and fellow- traveller Bayard Taylor called him, "a pioneer in the path of empire." Resigning from the Navy, Beale explored the desert trails and the moimtain passes which led overland to the Pacific, and later he surveyed the routes and built the wagon roads over which the mighty migration passed to people the new world beyond the Rockies. As Superintendent of the Indians, a thankless office which he filled for three years, Beale initiated a policy of honest dealing with the nation's wards iv Introductory Note which would have been even more successful than it was had cordial unfaltering support always been forthcoming from Washington. -

Early Psychological Warfare in the Hidalgo Revolt

Early Psychological Warfare In the Hidalgo Revolt HUGH M. HAMILL, JR.* OLONEL TORCUATO TRUJILLO had been sent on a desper Cate-almost hopeless-mission by the viceroy of New Spain.1 His orders were to hold the pass at Monte de las Cruces on the Toluca road over which the priest Miguel Hidalgo was expected to lead his insurgent horde. Trujillo's 2,500 men did have the topographical advantage, but the mob, one could hardly call it an army, which advanced toward the capital of the kingdom outnumbered them more than thirty to one. If the vain and un popular Spanish colonel failed, the rebels could march unhindered on Mexico City. On October 30, 1810, the forces clashed in a bloody and pro longed battle. It was the first time that the unwieldy mass of rebel recruits had faced disciplined soldiers and well serviced artillery in the field. Under such circumstances coordinated attack was dif ficult and Hidalgo's casualties were heavy. Toward nightfall Tru jillo's troop, though decimated, was able to break out of its encircled position and retreat into the Valley of Anahuac. The insurgents gained the heights of Las Cruces and advanced the next day over the divide and down to the hamlet of Cuajimalpa. The capital of New Spain lay below them. Why was the six weeks old revolution not consummated immediate ly by the occupation of Mexico City~ Why, after poising three days above the city, did Hidalgo abandon his goal and retreat~ *The author is assistant professor of history at Ohio Wesleyan University. -

Or, Early Times in Southern California. by Major Horace Bell

Reminiscences of a ranger; or, Early times in southern California. By Major Horace Bell REMINISCENCES —OF A— RANGER —OR,— EARLY TIMES —IN— SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA, By MAJOR HORACE BELL. LOS ANGELES: YARNELL, CAYSTILE & MATHES, PRINTERS. 1881. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1881, by HORACE BELL, In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D.C. TO THE FEW Reminiscences of a ranger; or, Early times in southern California. By Major Horace Bell http://www.loc.gov/resource/calbk.103 SURVIVING MEMBERS OF THE LOS ANGELES RANGERS, AND TO THE MEMORY OF THOSE WHO HAVE ANSWERED TO THE LAST ROLL-CALL, THIS HUMBLE TRIBUTE IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR. PREFACE. No country or section during the first decade following the conquest of California, has been more prolific of adventure than our own bright and beautiful land; and to rescue from threatened oblivion the incidents herein related, and either occurring under the personal observation of the author, or related to him on the ground by the actors therein, and to give place on the page of history to the names of brave and worthy men who figured in the stirring events of the times referred to, as well as to portray pioneer life as it then existed, not only among the American pioneers, but also the California Spaniards, the author sends forth his book of Reminiscences, trusting that its many imperfections may be charitably scrutinized by a criticising public, and that the honesty of purpose with which it is written will be duly appreciated. H. B. -

SOME EARLY HISTORY of OWENS RIVER VALLEY Author(S): J

SOME EARLY HISTORY OF OWENS RIVER VALLEY Author(s): J. M. GUINN Source: Annual Publication of the Historical Society of Southern California, Vol. 10, No. 3 (1917), pp. 41-47 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Historical Society of Southern California Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41168743 Accessed: 23-01-2020 02:15 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Historical Society of Southern California, University of California Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Annual Publication of the Historical Society of Southern California This content downloaded from 47.157.197.123 on Thu, 23 Jan 2020 02:15:37 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms SOME EARLY HISTORY OF OWENS RIVER VALLEY BY J. M. GUINN Since its connection to Los Angeles by the Aqueduct, Owens River Valley has become almost an appendage of our city. Of the thousands of people who use the water brought two hundred miles through the Owens River Aqueduct very few know anything of the early history of the river, the valley or the lake. Who discovei-ed the valley ? who named the lake and the river ? and for whom were they named ? are questions that would puzzle many of our local his- torians and confound the mass of its water users. -

Three Marshalls"

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 48 Number 1 Article 2 1-1-1973 The Divergent Paths of Frémont's "Three Marshalls" Harvey L. Carter Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Carter, Harvey L.. "The Divergent Paths of Frémont's "Three Marshalls"." New Mexico Historical Review 48, 1 (2021). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol48/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. 5 THE DIVERGENT PATHS OF FREMONT'S "THREE MARSHALLS" HARVEY L. CARTER IT WAS after dark on Sunday, January 20, 1849, that two gaunt and weary riders rode into Taos, New Mexico, from the snow covered San Luis Valley of Colorado. For two months they had battled without avail to force a passage over the Continental Divide along the direct line of the 38th parallel. Now they had abandoned the struggle with the elements and had ridden south for help to rescue the disorganized and demoralized remnants of the expedi tion that had hoped to find a direct westward route for a railroad from St. Louis to San Francisco. The older of the two men was thirty-seven. His full beard did not conceal the fatigue of body ,~md dejection of mind that were evident in his face. His companion, a handsome and well-built man of thirty, retained his usual energy t. -

Spanish Colonial Cartography, 1450–1700 David Buisseret

41 • Spanish Colonial Cartography, 1450–1700 David Buisseret In all of history, very few powers have so rapidly acquired The maps of Guatemala are relatively few,7 but those of as much apparently uncharted territory as the Spaniards Panama are numerous, no doubt because the isthmus was did in the first half of the sixteenth century. This acquisi- tion posed huge administrative, military, and political I would like to acknowledge the help of Anne Godlewska, Juan Gil, problems, among which was the problem of how the area Brian Harley, John Hébert, and Richard Kagan in the preparation of this chapter. might be mapped. The early sixteenth-century Spain of the Abbreviations used in this chapter include: AGI for Archivo General Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand II and Isabella I, initially de Indias, Seville. responded to this problem by establishing at Seville a great 1. Between 1900 and 1921, Pedro Torres Lanzas produced a series of cartographic center whose activities are described in chap- catalogs for the AGI. These have been reprinted under different titles ter 40 in this volume by Alison Sandman. However, as and, along with other map catalogs, are now being replaced by a com- puterized general list. See Pedro Torres Lanzas, Catálogo de mapas y time went by, other mapping groups emerged, and it is planos de México, 2 vols. (reprinted [Madrid]: Ministerio de Cultura, their work that will be described in this chapter. After Dirección General de Bellas Artes y Archivos, 1985); idem, Catálogo de considering the nature of these groups, we will discuss mapas y planos: Guatemala (Guatemala, San Salvador, Honduras, their activities in the main areas of Spain’s overseas Nicaragua y Costa Rica) (reprinted [Spain]: Ministerio de Cultura, Di- possessions. -

California Landmarks

Original Historical Landmarks Index to Books I, II and III Plaques Dedicated by Grand Parlor, Parlors, or Parlors with Other Groups September 2009 Native Daughters of the Golden West 543 Baker Street San Francisco, California 94117-1405 Monument Vol 1-3.doc, September 17, 2009 Index to Original Historical Landmarks, Books I, II and III Page 2 of 38 Dedications with Native Sons of the Golden West are indicated by “+” Dedications with Other Groups are indicated by “++” County Plaque Dedicated Parlor Location Description Bk/Pge Goal 1/001 Dedication 1/003 Presentation 1/005 Sponsor 1/009 Founder, Lilly Dyer 1/013 State Information Name, Motto, etc. 1/014 Thirty First Star 1/017 1/020 Flags of California 1/021 State Seal 1/027 Mothers Day May 9, 1971 Grin and Bear It Cartoon 1/029 N. D. G. W. Directory 1/031 Landmarks Title Page 1/035 Historic California Missions 1965 Pamphlet 1/047 1/051 Mission Soledad 1/052 Mission Nuestra Senora County Road, Mission 1/053 Restored mission, Registered Dolorosisima De La Oct 14, 1956 NDGW Grand Parlor District, Soledad, Monterey 1/054 Landmark No. 233 Soledad Co. 1/055 Mission Picture 1/057 Subordinate Parlor Title Page 1/061 Landmarks Alameda * Parlor Listing Title Page 1/065 Church of St. James the Foothill Blvd and 12th Founded June 27,1858 by first 1/066 Alameda Dec 6, 1959 Fruitvale No. 177, ++ Apostle Ave., E. Oakland Episcopal Bishop of California 1/067 Berkeley No. 150, Bear Flag No. 151, Sequoia No. 1302-1304 Abina Street, 1841 – site of first dwelling in Alameda Domingo Peralta Adobe Mar 22, 1970 1/069 272, Albany No.