History of San Diego, 1542-1908

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grants of Land in California Made by Spanish Or Mexican Authorities

-::, » . .• f Grants of Land in California Made by Spanish or Mexican Authorities Prepared by the Staff of the State Lands Commission ----- -- -·- PREFACE This report was prepared by Cris Perez under direction of Lou Shafer. There were three main reasons for its preparation. First, it provides a convenient reference to patent data used by staff Boundary Officers and others who may find the information helpful. Secondly, this report provides a background for newer members who may be unfamiliar with Spanish and Mexican land grants and the general circumstances surrounding the transfer of land from Mexican to American dominion. Lastly, it provides sources for additional reading for those who may wish to study further. The report has not been reviewed by the Executive Staff of the Commission and has not been approved by the State Lands Commission. If there are any questions regarding this report, direct them to Cris Perez or myself at the Office of the State Lands Commission, 1807 - 13th Street, Sacramento, California 95814. ROY MINNICK, Supervisor Boundary Investigation Unit 0401L VI TABLE OF CONTENlS Preface UI List of Maps x Introduction 1 Private Land Claims in California 2 Missions, Presidios, and Pueblos 7 Explanation of Terms Used in This Report 14 GRANTS OF LAND BY COUNTY AlamE:1da County 15 Amador County 19 Butte County 21 Calaveras County 23 Colusa County 25 Contra Costa County 27 Fresno County 31 Glenn County 33 Kern County 35 Kings County 39 Lake County 41 Los Angeles County 43 Marin County 53 Mariposa County 57 Mendocino County -

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Sacramento District 1325 J Street Sacramento, California Contract: DACA05-97-D-0013, Task 0001 FOSTER WHEELER ENVIRONMENTAL CORPORATION

CALIFORNIA HISTORIC MILITARY BUILDINGS AND STRUCTURES INVENTORY VOLUME II: THE HISTORY AND HISTORIC RESOURCES OF THE MILITARY IN CALIFORNIA, 1769-1989 by Stephen D. Mikesell Prepared for: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Sacramento District 1325 J Street Sacramento, California Contract: DACA05-97-D-0013, Task 0001 FOSTER WHEELER ENVIRONMENTAL CORPORATION Prepared by: JRP JRP HISTORICAL CONSULTING SERVICES Davis, California 95616 March 2000 California llistoric Military Buildings and Stnictures Inventory, Volume II CONTENTS CONTENTS ..................................................................................................................................... i FIGURES ....................................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF ACRONYMS .................................................................................................................. iv PREFACE .................................................................................................................................... viii 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1-1 2.0 COLONIAL ERA (1769-1846) .............................................................................................. 2-1 2.1 Spanish-Mexican Era Buildings Owned by the Military ............................................... 2-8 2.2 Conclusions .................................................................................................................. -

Summer 2019, Volume 65, Number 2

The Journal of The Journal of SanSan DiegoDiego HistoryHistory The Journal of San Diego History The San Diego History Center, founded as the San Diego Historical Society in 1928, has always been the catalyst for the preservation and promotion of the history of the San Diego region. The San Diego History Center makes history interesting and fun and seeks to engage audiences of all ages in connecting the past to the present and to set the stage for where our community is headed in the future. The organization operates museums in two National Historic Districts, the San Diego History Center and Research Archives in Balboa Park, and the Junípero Serra Museum in Presidio Park. The History Center is a lifelong learning center for all members of the community, providing outstanding educational programs for schoolchildren and popular programs for families and adults. The Research Archives serves residents, scholars, students, and researchers onsite and online. With its rich historical content, archived material, and online photo gallery, the San Diego History Center’s website is used by more than 1 million visitors annually. The San Diego History Center is a Smithsonian Affiliate and one of the oldest and largest historical organizations on the West Coast. Front Cover: Illustration by contemporary artist Gene Locklear of Kumeyaay observing the settlement on Presidio Hill, c. 1770. Back Cover: View of Presidio Hill looking southwest, c. 1874 (SDHC #11675-2). Design and Layout: Allen Wynar Printing: Crest Offset Printing Copy Edits: Samantha Alberts Articles appearing in The Journal of San Diego History are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. -

Historical Backgrounds of Range Land Use in California

While accounts of contemporary Historical Backgrounds of Range Land Use travelers are of great value in giv- ing us an appraisal of the general in California nature of the forage cover at the time California was being settled L. T. BURCHAM they afford few details of its bo- Senior Forest Technician, Ccrlifomia Division of Forestry, tanical composition or floristic Sawamento, California. characteristics. It is to early bo- tanical collections that we must In the year 1769 a group of Pedro Fages said: “For flocks and turn for these details. They range Spaniards was riding northward herds there are excellent places all the way from fragmentary col- from San Diego, through the Coast with plenty of water and abun- lections such as those of the Ranges, in search of the Port of dance of pasture” (Fages, 1937). Beechey voyage to the more com- Monterey. Members of that party, At San Luis Obispo, he wrote, prehensive work of the Pacific an expedition led by Don Gaspar “Abundant water is found in every railroad surveys (Hooker and Ar- de Portola, were the first Euro- direction, and pasture for the cat- nott, 1841; Torrey, 1856). In a peans to gain any extensive, accu- tle, so that no matter how large sense early plant collections are rate knowledge of California. On the mission grows to be . the quite disappointing to a range Tuesday, July 18, 1769, one of land promises sustenance” (Fages, man. They were made almost these men, Miguel Costanso, wrote : 1937). But perhaps none of these wholly to serve taxonomic or other “The place where we halted was accounts excelled the simple elo- special purposes; they are chiefly exceedingly beautiful and pleasant, quence of Fray Juan Crespi, who records of occurrence, yielding but a valley remarkable for its size, wrote : “There is much land and meager information as to relative adorned with groves of trees, and good pasture” (Engelhardt, 1920), abundance and area1 distribution covered with the finest pasture . -

Newsletter Norman F

The Society for Historical Archaeology NEWSLETTER NORMAN F. BARKA, Newsletter Editor DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY, COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY, WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA 23185 Volume 15 Number 2 June 1982 INDEX page On a happier note, the Society is pleased to announce the receipt of a fourth royalty EDITOR'S CORNER................... 1 check for $608.85 from sale,s of Historical IMPORTANT MESSAGE.................. 1 Archaeology: ! Guide to Substantive and NOMINATIONS FOR ELECTION........... 2 Theoretical Contributions, edited by Robert 1983 SHA/CUA ANNUAL MEETINGS....... 2 ScQuyler. Bob Schuyler has also decided to LEGISLATIVE AFFAIRS................ 5 have one-half of all the royalties from the REQUESTS FOR INFORMATION........... 7 sale of Archaeological Perspectives ~ PAST CONFERENCES................... 7 Ethnicity in America given to SHA to help BOOK REVIEWS....................... 16 its scholarly publication program. RECENT PUBLICATIONS................ 17 SHA salutes Bob and the Baywood Publishing CURRENT RESEARCH ••••••••••••••••••• 25 Coiiipany. ADVISORY COUNCIL ON UNDERWATER Finally, the Current Research section of ARCHAEOLOGy ••••••••••••••••••••• 45 this Newsletter will have a short report on the historical archaeology of Indonesia. News of relevant research in other areas of EDITOR'S CORNER the Third World will be welcomed for future editions of the Newsletter. Vandalism of archaeological remains has always been a serious problem, especially on private property, over which historic pre IMPORTANT MESSAGE FOR ALL SHA MEMBERS servation -

A Companion to the American West

A COMPANION TO THE AMERICAN WEST Edited by William Deverell A Companion to the American West BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO HISTORY This series provides sophisticated and authoritative overviews of the scholarship that has shaped our current understanding of the past. Defined by theme, period and/or region, each volume comprises between twenty- five and forty concise essays written by individual scholars within their area of specialization. The aim of each contribution is to synthesize the current state of scholarship from a variety of historical perspectives and to provide a statement on where the field is heading. The essays are written in a clear, provocative, and lively manner, designed for an international audience of scholars, students, and general readers. Published A Companion to Western Historical Thought A Companion to Gender History Edited by Lloyd Kramer and Sarah Maza Edited by Teresa Meade and Merry E. Weisner-Hanks BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO BRITISH HISTORY Published In preparation A Companion to Roman Britain A Companion to Britain in the Early Middle Ages Edited by Malcolm Todd Edited by Pauline Stafford A Companion to Britain in the Later Middle Ages A Companion to Tudor Britain Edited by S. H. Rigby Edited by Robert Tittler and Norman Jones A Companion to Stuart Britain A Companion to Nineteenth-Century Britain Edited by Barry Coward Edited by Chris Williams A Companion to Eighteenth-Century Britain A Companion to Contemporary Britain Edited by H. T. Dickinson Edited by Paul Addison and Harriet Jones A Companion to Early Twentieth-Century Britain Edited by Chris Wrigley BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO EUROPEAN HISTORY Published A Companion to Europe 1900–1945 A Companion to the Worlds of the Renaissance Edited by Gordon Martel Edited by Guido Ruggiero Planned A Companion to the Reformation World A Companion to Europe in the Middle Ages Edited by R. -

The Conflict Between the California Indian and White Civilization:Iii

I BE RO ... AM E RICA,N A: 23 THE CONFLICT BETWEEN THE CALIFORNIA INDIAN AND WHITE CIVILIZATION:III S. F. COOK -c - THE CONFLICT BETWEEN THE CALIFORNIA INDIAN AND' WHITE CIVILIZATION III. THE AMERICAN INVASION, 1848-1870 BY S. F. COOK UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND LOS ANGELES 1943 CONTENTS IBERO-AMERICANA: 23 EDITORS: C. O. SAUER, LAWRENCE KINNAIRD, L. B. SIMPSON PART THREE. THE AMERICAN INVASION, 1848-1870 II5 pages PAGE Submitted by editors February 13, 1942 Introduction. I Issued April 20, 1943 Price, $1.25 Military Casualties, 1848-1865 . Social Homicide Disease. Food and Nutrition UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND Los ANGELES Labor . CALIFORNIA Sex and Family Relations Summary and Comparisons CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON,ENGLAND APPENDIX Table 1. Indian Population from the End of the Mission Period to Modern Times . Table 2. Estimated Population in 1848, 1852, and 1880 . Koupi od ~ Table 3. Indian Losses from Military Operations, 1847- Darem od u ~:ij3.A 1865 ............... 106 V Table 4. Population Decline due to Military Casualties, 1848-1880. III IllV b Table 5. Social Homicide, 1852-1865 II2 . C' . ",I PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA The American Invasion, 1848-1870 INTRODUCTION HEN THE CALIFORNIA INDIAN was confronted with the prob lem of contact and competition with the white race, his suc W cess was much less marked with the Anglo-American than with the Ibero-American branch. To be sure, his success against the latter had been far from noteworthy; both in the missions and in the native habitat the aboriginal population'had declined, and the Indian had been forced to give ground politically and racially before the advance of Spanish colonization. -

San Diego History Center Is a Museum, Education Center, and Research Library Founded As the San Diego Historical Society in 1928

The Jour nal of Volume 56 Winter/Spring 2010 Numbers 1 & 2 • The Journal of San Diego History San Diego History 1. Joshua Sweeney 12. Ellen Warren Scripps 22. George Washington 31. Florence May Scripps 2. Julia Scripps Booth Scripps Kellogg (Mrs. James M.) 13. Catherine Elizabeth 23. Winifred Scripps Ellis 32. Ernest O’Hearn Scripps 3. James S. Booth Scripps Southwick (Mrs. G.O.) 33. Ambrosia Scripps 4. Ellen Browning Scripps (Mrs. William D.) 24. William A. Scripps (Mrs. William A.) 5. Howard “Ernie” Scripps 14. Sarah Clarke Scripps 25. Anna Adelaide Scripps 34. Georgie Scripps, son 6. James E. Scripps (Mrs. George W.) (Mrs. George C.) of Anna and George C. 7. William E. Scripps 15. James Scripps Southwick 26. Baby of Anna and Scripps 8. Harriet Messinger 16. Jesse Scripps Weiss George C. Scripps 35. Hans Bagby Scripps (Mrs. James E.) 17. Grace Messinger Scripps 27. George H. Scripps 36. Elizabeth Sweeney 9. Anna Scripps Whitcomb 18. Sarah Adele Scripps 28. Harry Scripps (London, (Mrs. John S., Sr.) (Mrs. Edgar B.) 19. Jessie Adelaide Scripps England) 37. John S. Sweeney, Jr. 10. George G. Booth 20. George C. Scripps 29. Frederick W. Kellogg 38. John S. Sweeney, Sr. 11. Grace Ellen Booth 21. Helen Marjorie 30. Linnie Scripps (Mrs. 39. Mary Margaret Sweeney Wallace Southwick Ernest) Publication of The Journal of San Diego History is underwritten by a major grant from the Quest for Truth Foundation, established by the late James G. Scripps. Additional support is provided by “The Journal of San Diego Fund” of the San Diego Foundation and private donors. -

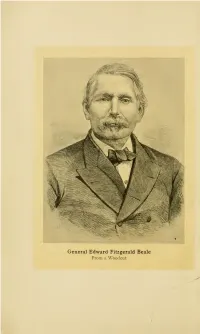

Edward Fitzgerald Beale from a Woodcut Edward Fitzgerald Beale

General Edward Fitzgerald Beale From a Woodcut Edward Fitzgerald Beale A Pioneer in the Path of Empire 1822-1903 By Stephen Bonsai With 17 Illustrations G. P. Putnam's Sons New York and London Ube ftnicfterbocfter press 1912 r6n5 Copyright, iqi2 BY TRUXTUN BEALE Ube finickerbocher pteee, 'Mew ]|?ocft £CI.A;n41 4S INTRODUCTORY NOTE EDWARD FITZGERALD BEALE, whose life is outlined in the following pages, was a remarkable man of a type we shall never see in America again. A grandson of the gallant Truxtun, Beale was bom in the Navy and his early life was passed at sea. However, he fought with the army at San Pasqual and when night fell upon that indecisive battlefield, with Kit Carson and an anonymous Indian, by a daring journey through a hostile country, he brought to Commodore Stockton in San Diego, the news of General Kearny's desperate situation. Beale brought the first gold East, and was truly, in those stirring days, what his friend and fellow- traveller Bayard Taylor called him, "a pioneer in the path of empire." Resigning from the Navy, Beale explored the desert trails and the moimtain passes which led overland to the Pacific, and later he surveyed the routes and built the wagon roads over which the mighty migration passed to people the new world beyond the Rockies. As Superintendent of the Indians, a thankless office which he filled for three years, Beale initiated a policy of honest dealing with the nation's wards iv Introductory Note which would have been even more successful than it was had cordial unfaltering support always been forthcoming from Washington. -

Army and Navy Review 1915 Panama-California Edition

I I ■ ' % W T -• 4 . -■ . :. ;!t'v i, i ' •• 1-s- .. m I ^ 1 1 T % © i r «V,;;> f A r, Tf>. % ,~ — l * ** • .v «a» , -. • . r* *•- *?sr - T 7 v-v * • >*~v s* • T LiJL'i i. iO i% ARMY AND NAVY REVIEW Copyrighted, 1915 ARMY AMD NAVY REVIEW 19 15 ARMY and NAVY REVIEW BEING A REVIEW OF THE ACTIVITIES OF THE OFFICERS AND ENLISTED MEN STATIONED IN SAN DIEGO DURING THE EXPOSITION SECTIONS 1. SAN DIEGO AND THE PANAMA- CALIFORNIA EXPOSITION. 2 .ARTILLERY. 3. CAVALRY. 4. SIGNAL SERVICE AND AVIATION SCHOOL. 5. T H E N A V Y . 6 . MARINE CORPS. 7. ATHLETICS. 8 . EDITORIAL AND COMMENT. Army and Navy Review Staff ARTHUR ARONSON, Managing Editor CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: LIEUT. COL. W M . C. DAVIS, U. S. Army COL. JOSEPH H. PENDLETON, U. S. M. C. CHAPLAIN JOSEPH L. HUNTER, C. A.C. CAPTAIN CHARLES H. LYMAN, U. S. M. C. CHIEF YEOMAN GEORGE P. PITKIN, U. S. Navy SERGEANT MAJOR THOMAS F. CARNEY, U. S. M. C. SERGEANT MAJOR J. A. BLANKENSHIP, First Cavalry SERGEANT MAJOR PAUL KINGSTON, C. A. C. OTHER ARTICLES BY EDW IN M. CAPPS, Ma^or G. A. DA V IDSON , Pres. Panama-California Exposition D. C. COLLIER, Ex-Pres. Panama-California Exposition HERBERT R. FAT, Major C. A. C., National Guard of California Presentation any a year will pass before the words “1915 and San Diego” will fade from the minds of some four thousand en listed men. The experiences, adven tures, joys and pleasures were great indeed. M en of the different Arms became friends here; San Diego was thankful for their services and the men were thankful, being stationed here. -

SHPO/External Stakeholder) Ser 00/054 and Response by the Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation

Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation P.O. Box 23130 San Diego, CA 92193 Captain S.F. Adams Commanding Officer Department of the Navy Naval Base Point Loma 140 Sylvester Road San Diego, CA 92106-3521 May 1, 2012 Subject: Attachment to the Question (SHPO/External Stakeholder) Ser 00/054 and Response by the Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation Thank you for the opportunity to comment on your questionnaire sent February 7, 2012. Given the problems associated with eviction from Naval Base Point Loma between verbal notification on November 10, 2012 and removal of our private property by December 31, 2012, we could not meet your February 17, 2012 deadline. The following are our responses to your questions. Does the installation communicate with stakeholders as required? Response: Naval Base Point Loma terminated its best line of communication with public stakeholders concerned with cultural resources. From 1996 through 2011 The US Navy and the Ft Guijarros Museum Foundation held a Cultural Resource Agreement in compliance with Section 110 of the National Historic Preservation Act. Termination of the agreement also eliminated access to the historical and archaeological records owned by the Fort Guijarros Museum Foundation and formerly housed in Building 127 at the Naval Base Pont Loma. Elimination also terminated review of the archaeological records for Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act, and any stakeholder evaluation of construction impacts to National Register eligible properties on Naval Base Point Loma. Since reorganization to Navy Region Southwest in 1999 and recent combining of the formerly independent Environmental Office into Naval Facilities Engineering Command, communication with stakeholders dropped to an all time low. -

Or, Early Times in Southern California. by Major Horace Bell

Reminiscences of a ranger; or, Early times in southern California. By Major Horace Bell REMINISCENCES —OF A— RANGER —OR,— EARLY TIMES —IN— SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA, By MAJOR HORACE BELL. LOS ANGELES: YARNELL, CAYSTILE & MATHES, PRINTERS. 1881. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1881, by HORACE BELL, In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D.C. TO THE FEW Reminiscences of a ranger; or, Early times in southern California. By Major Horace Bell http://www.loc.gov/resource/calbk.103 SURVIVING MEMBERS OF THE LOS ANGELES RANGERS, AND TO THE MEMORY OF THOSE WHO HAVE ANSWERED TO THE LAST ROLL-CALL, THIS HUMBLE TRIBUTE IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR. PREFACE. No country or section during the first decade following the conquest of California, has been more prolific of adventure than our own bright and beautiful land; and to rescue from threatened oblivion the incidents herein related, and either occurring under the personal observation of the author, or related to him on the ground by the actors therein, and to give place on the page of history to the names of brave and worthy men who figured in the stirring events of the times referred to, as well as to portray pioneer life as it then existed, not only among the American pioneers, but also the California Spaniards, the author sends forth his book of Reminiscences, trusting that its many imperfections may be charitably scrutinized by a criticising public, and that the honesty of purpose with which it is written will be duly appreciated. H. B.