India's Changing Cityscapes: Work, Migration and Livelihoods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 in the High Court of Karnataka at Bengaluru

1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF KARNATAKA AT BENGALURU DATED THIS THE 13TH DAY OF JUNE 2016 PRESENT THE HON'BLE MR.SUBHRO KAMAL MUKHERJEE, CHIEF JUSTICE AND THE HON'BLE MR.JUSTICE RAVI MALIMATH WRIT PETITION NOS.1514-1515/2016 (LA-RES-PIL) BETWEEN 1. NARASIMHA NAIK S/O SHIVALINGA NAIK AGED ABOUT 58 YEARS OCC:AGRICULTURE & FARMERS LEADER OF HUTTI, KOTHA & MEDINAPUR JOINT VILLAGES LAND LOOSERS PROTESTING COMMITTEE, HATTI R/O KOTHA, TALUK: LINGASUGUR DISTRICT:RAICHUR 2. KRISHNAPPA S/O CHANDRAPPA AGED ABOUT 54 YEARS OCC:PRESIDENT OF HUTTI, KOTHA & MEDINAPUR JOINT VILLAGES LAND LOOSERS PROTESTING COMMITTEE HATTI, R/O KOTHA, TALUK:LINGASUGUR DISTRICT:RAICHUR ... PETITIONERS (BY SRI G G CHAGASHETTY, ADVOCATE) AND 1. THE STATE OF KARNATAKA BY ITS SECRETARY DEPARTMENT OF INDUSTRIES & COMMERCE M S BUILDING, BANGALORE-560001 2. THE DEPUTY COMMISSIONER RAICHUR, RAICHUR DISTRICT-584101 2 3. THE ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER LINGASUGUR RAICHUR DISTRICT-584101 4. THE HATTI GOLD MINES CO. LTD., (A GOVERNMENT OF KARNATAKA UNDERTAKING), PO:HUTTI-584115 DISTRICT:RAICHUR REP BY ITS EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR ... RESPONDENTS (BY SRI H VENKATESH DODDERI, AGA FOR R-1 TO 3; SRI K. RAMACHANDRAN, ADVOCATE FOR SRI M R C RAVI, ADVOCATE FOR R-4) THESE WRIT PETITIONS ARE FILED UNDER ARTICLES 226 AND 227 OF THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA PRAYING TO DIRECT THE RESPONDENTS TO TAKE SUITABLE DECISION ON THE REPRESENTATION MADE BY THE PETITIONERS ON BEHALF OF SAMITHI DATED 15.06.2015 AND 29.06.2015 PRODUCED AT ANNEXURES-D AND E AND TO TAKE SUITABLE DECISION IN ACCORDANCE WITH LAW. THESE WRIT PETITIONS COMING ON FOR PRELIMINARY HEARING THIS DAY, CHIEF JUSTICE MADE THE FOLLOWING: ORDER The writ petitioners, who are, allegedly, the land loosers, seek for a direction for their employment in Hatti Gold Mines Company Limited. -

In the High Court of Karnataka Kalaburagi Bench

1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF KARNATAKA KALABURAGI BENCH DATED THIS THE 17 TH DAY OF DECEMBER 2014 BEFORE THE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE ASHOK B. HINCHIGERI WRIT PETITION Nos.207050/2014 & 207278-279/2014 (S-RES) BETWEEN : 1. Sreedhara Patil S/o Hanumangouda Age: 25 years, Occ: Unemployed R/o Jalahalli, Tq. Deodurg Dist: Raichur 2. Veeresh S/o Sharnappa Age: 25 years, Occ: Unemployed R/o Lingasugur, Dist: Raichur 3. Adappa S/o Channabassappa Age: 34 years, Occ: unemployed R/o Kota Village, Tq. Lingasugur Dist: Raichur ... Petitioners (By Sri Ravindra Reddy, Advocate) AND: 1. The State of Karnataka By its Secretary Department of Mines and Zeology, Vidhana Soudha Bangalore – 560 001. 2 2. The Managing Director of Hutti Gold Mines Company Ltd., Hutti Tq. Lingasugur Dist. Raichur – 584101. 3. The General Manager Co-ordination Hutti Gold Mines Company Ltd., Hutti, Tq. Lingasugur Dist. Raichur – 584101 4. The Head of the Department of Engineering Hutti Gold Mines Company Ltd., Hutti, Tq. Lingasugur Dist. Raichur – 584101 5. The Head of the Department of Mining Hutti Gold Mines Company Ltd., Hutti, Tq. Lingasugur Dist. Raichur – 584101 6. The Head of the Department of Administration of Hutti Gold Mines Company Ltd., of Hutti, Tq. Lingasugur Dist. Raichur – 584101 7. The Head of the Department of Metallurgy of Hutti Gold Mines Company Ltd., Hutti Tq. Lingasugur, Dist. Raichur – 584101 ... Respondents (By Sri Shivakumar Tengli, AGA for R1) 3 These writ petitions are filed under Articles 226 & 227 of the Constitution of India praying to issue writ of certiorari quashing impugned list dated 24.11.2014 in No. -

Factiva RTF Display Format

HD Agribusiness; Data from Kuvempu University Advance Knowledge in Agribusiness [Biochemical changes in the composition of developing seeds of Pongamia pinnata (L.) Pierre] WC 403 words PD 7 August 2014 SN Agriculture Week SC AGRWEK PG 42 LA English CY © Copyright 2014 Agriculture Week via NewsRx.com LP 2014 AUG 7 (VerticalNews) -- By a News Reporter-Staff News Editor at Agriculture Week -- A new study on Agribusiness is now available. According to news originating from Karnataka, India, by VerticalNews correspondents, research stated, "The biochemical changes occurring in developing Pongamia pinnata seeds were determined at an interval of three weeks from 30 weeks up to 42 weeks after flowering. Significant variation in total sugar, starch, lipid, protein and oil body associated protein contents was documented." TD Our news journalists obtained a quote from the research from Kuvempu University, "The total carbon content decreased significantly, while nitrogen content increased. Significant variation in mineral nutrient content was also detected across all the stages of seed development. Oil body associated protein-specific band between 20 and 19 kDa was prominently observed at later stages of seed development Phytic acid contentincreased from 0.58 to 2.35%. Steady decrease in chlorophyll content from 0.175 to 0.013 mg g(-1) of seed dry wt. was observed. Electrical conductivity decreased during the seed development. The crude fibre content increased, while the ash content remained constant at all stages of seed maturity. Quantitative changes in amino acids during seed development were observed. Seeds harvested at 42 weeks after flowering had maximum physiological maturity with high oil content and seed reserve material." According to the news editors, the research concluded: "The base line data of pongamia seed development could be used in the furtherance of knowledge relating to molecular, physiological and genetic aspects regulating biosynthetic pathways of reserve materials." Page 1 © 2014 Factiva, Inc. -

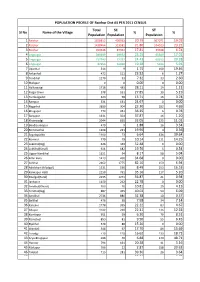

Sl No Name of the Village Total Population SC Population % ST

POPULATION PROFILE OF Raichur Dist AS PER 2011 CENSUS Total SC ST Sl No Name of the Village % % Population Population Population 1 Raichur 1928812 400933 20.79 367071 19.03 2 Raichur 1438464 313581 21.80 334023 23.22 3 Raichur 490348 87352 17.81 33048 6.74 4 Lingsugur 385699 89692 23.25 65589 17.01 5 Lingsugur 297743 72732 24.43 60393 20.28 6 Lingsugur 87956 16960 19.28 5196 5.91 7 Upanhal 514 9 1.75 100 19.46 8 Ankanhal 472 111 23.52 6 1.27 9 Tondihal 1270 93 7.32 33 2.60 10 Mallapur 0 0 0.00 0 0.00 11 Halkawatgi 1718 483 28.11 19 1.11 12 Palgal Dinni 578 161 27.85 30 5.19 13 Tumbalgaddi 423 58 13.71 16 3.78 14 Rampur 531 131 24.67 0 0.00 15 Nagarhal 3880 904 23.30 182 4.69 16 Bhogapur 773 281 36.35 6 0.78 17 Baiyapur 1331 504 37.87 16 1.20 18 Khairwadgi 2044 655 32.05 225 11.01 19 Bandisunkapur 479 9 1.88 16 3.34 20 Bommanhal 1108 221 19.95 4 0.36 21 Sajjalagudda 1100 73 6.64 436 39.64 22 Komnur 779 79 10.14 111 14.25 23 Lukkihal(Big) 646 339 52.48 0 0.00 24 Lukkihal(Small) 921 182 19.76 5 0.54 25 Uppar Nandihal 1151 94 8.17 58 5.04 26 Killar Hatti 1413 490 34.68 0 0.00 27 Ashihal 2162 1775 82.10 150 6.94 28 Advibhavi (Mudgal) 1531 130 8.49 253 16.53 29 Kannapur Hatti 2250 791 35.16 117 5.20 30 Mudgal(Rural) 2235 1271 56.87 21 0.94 31 Jantapur 1150 262 22.78 0 0.00 32 Yerdihal(Khurd) 703 76 10.81 29 4.13 33 Yerdihal(Big) 887 355 40.02 54 6.09 34 Amdihal 2736 886 32.38 10 0.37 35 Bellihal 476 38 7.98 34 7.14 36 Kansavi 1778 395 22.22 83 4.67 37 Adapur 1022 228 22.31 126 12.33 38 Komlapur 951 59 6.20 79 8.31 39 Ramatnal 853 81 9.50 55 -

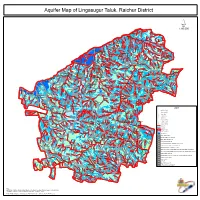

Aquifer Map of Lingasugur Taluk, Raichur District

Aquifer Map of Lingasugur Taluk, Raichur District ´ GADAGI "/ 1:80,000 GADAGI "/ PAIDODDI "/ TAMMANKAL "/ *# GF TAMMANKAL *#"/ GF *# *#*# RAIDURG *# *#"/ GF *# *#*# *# # (! *# * GOLAPALLI *# GF "/ *#AIDABHAVI (!YERAJANTI "/*# *# *# "/ *# *# (! (! RAMAROTI *# *# (! "/ *# *# GF (! GF *# (! *# *# *# *# GF *# *# GF *# *# *# *# *# (! GF *# *# *# GF *#*# *# *# BANDEBHAVI *# (! *# (! *# *# GURGU*#NTA "/ YERGODI *# *# # *#*# "/ * "/ # *# *# GF KADADARAKERIGUNT*AGOLA (! # GF *# "/ "/ *# * *# *# GONAVATALA *# (! (! "/ *# (! PARAMPUR *# *# *# (! YELGUNDI GF (! "/ *# GF *# (! *# "/ *# # *# # *# *# *# * *# * *# *# GF *# GF GF (! YELAGATTI *# PARAMPUR *# GF *# "/ *# *# *# "/ *# *# *# *# GF *# GAUDUR *# *# (! *# GF *# *# MACHANUR *# GF *# GF *# *# "/ *# "/ *# *# *# *# GF *# *# *# *# *# *# *# *# *# *# HANCHNAL (! *# GF *# *# *# GF "/ *# *# *# *# *# *# *# *# GF GF JALDURG (! *# *# *# *# *# *# GF *# "/ GONUNTLA TANDA *# *# *# *# *# GF GF *# GF "/ *# DEVARBHUPUR *# *# *# # *# "/ *# *# *# *# *# *# * GF *# *# *# *# GF *# *# *#*# GF *# # *# *# *# *# * *# *# *#*# *# *# *# *# *# *# MADRAINAKOTA *# *# *# KODDON*#I *# *# GF *# (!(! "/ *# *# # "/ *# *# *# # *# *# *# * *# GF GF PHULBHAV*#I TAN*DA *# # *#*# *# *# *# GF "/ *# *# * *# *# *# TUGGLI GF*# PHGFULBHAVI*# *# *# *# *# TAV"/AG *# *# GF *# *# *# *#*# "/ GF "/ *# *# GF *# *# *# *# *# *# *# *# "/ *# RODALBANDI *# MINCHERI TANDA *# *# *# *# *# GF GF *# *# "/*# KALAPUR TANDA *#*# *# *#*# GF *# *# *# GF *# *# *# YARDONI *# *# *# *# *# *# *# GF"/*# "/ *# *# *# *# *# *# GONWATAL# GF *# *# *# *# *# *# *# MALLAPUR *#*# -

Lingasugur Bar Association : Lingasugur Taluk : Lingasugur District : Raichur

3/17/2018 KARNATAKA STATE BAR COUNCIL, OLD KGID BUILDING, BENGALURU VOTER LIST POLING BOOTH/PLACE OF VOTING : LINGASUGUR BAR ASSOCIATION : LINGASUGUR TALUK : LINGASUGUR DISTRICT : RAICHUR SL.NO. NAME SIGNATURE SHANKARGOWDA PAMPANGOUDA PATIL MYS/425/62 1 S/O PAMPANGOUDA PATIL ADVOCATE S.P. COMPLEX VIJAYA BANK ROAD LINGASUGUR RAICHUR 584122 MALLIKARJUN VENKATRAO JAGIRDAR MYS/174/68 2 S/O ADVOCATE BASAVESHWAR NAGAR : LINGASUGUR RAICHUR PATIL JAKKANAGOUDA BALANAGOUDA MYS/140/74 3 S/O BALANAGOUDA PATIL NEAR VIJAYA BANK NEAR GOVT HOSPITAL LINGASUGUR RAICHUR 584 122 KANAKAGIRI KASHIVISHWANATH VITHOBANNA KAR/321/77 4 S/O K. VITHOBANNA SHETTY VAIBHAVI NILAYA, HANUMAN CHOUK ,LINGASUGUR LINGASUGUR RAICHUR 584 122 1/28 3/17/2018 PATIL SHARANABASAVARAJ SANGANGOUDA KAR/155/79 5 S/O K SANGANAGOWDA LINGASUGUR LINGASUGUR RAICHUR 584122 AMARAPUR NAGAPPA KAR/427/79 S/O RAMAPPA 6 ADVOCATE RAGAVENDRA NILAYA,LAKSHMI NAGAR LINGASUGUR RAICHUR BALEGOUDA MALLIKARJUN AMARAPPA KAR/520/79 7 S/O AMARAPPA BALEGOWDA ADVOCATE HOUSING BOARD COLONY, M LINGASUGUR RAICHUR 584122 NAGALAPUR SHARANAPPA SHADAKSHARAPPA KAR/375/80 8 S/O SHADAKSHARAPPA OPP: COURT.SUB-JAIL AREA ,POST LINGASUGUR RAICHUR 584122 MAHABOOB ALI KAR/470/80 9 S/O RAJ MOHAMMED SAB ADVOCATE LINGASUGUR LINGASUGUR RAICHUR 584122 2/28 3/17/2018 IMADI AYYAPPA HANAMARADDEPPA KAR/474/82 10 S/O HANAMARADDEPPA KHB COLONY ,LINGASUGAR LINGASUGUR RAICHUR 584122 RAJASHEKHAR HONNAPPA KAR/73/83 11 S/O HONAPPA I.B. ROAD LINGASUGUR RAICHUR 584122 AMARESHWAR LINGARAJ SOMASHEKAR RAO KAR/30/86 12 S/O SOMASHEKAR RAO POST: MEDIKINHAL. LINGASUGUR RAICHUR SUNANDA SIDRAMAPPA BIRADAR KAR/872/90 D/O SIDRAMAPPA 13 W/O AMARASUNDAPPA. -

City Wise Progress

CITY wise details of PMAY(U) Financial Progress (Rs in Cr.) Physical Progress (Nos) Sr. Central Central State /City Houses Houses Houses No. Investment Assistance Assistance Sanctioned Grounded* Completed* Sanctioned Released A&N Island 1 Port Blair 151.59 8.96 0.46 598 38 25 Andhra Pradesh 1 Penukonda 200.68 62.43 - 4162 3 0 2 Thallarevu 0.58 0.35 0.15 23 23 12 3 Pendurthi 268.45 120.57 28.37 8038 1030 264 4 Naidupeta 288.43 68.84 36.18 4592 3223 2430 5 Amaravati 360.24 76.27 76.36 5069 5069 5069 6 Hukumpeta 0.19 0.02 0.02 1 1 1 7 Palakonda 83.36 35.55 9.40 2364 1218 969 8 Tekkali 515.94 219.62 13.61 14641 93 0 9 Anandapuram 0.29 0.02 0.02 1 1 1 10 Anandapuram 0.12 0.03 0.03 1 1 1 11 Kothavalasa 0.26 0.01 0.01 2 2 2 12 Thotada 0.60 0.06 0.06 3 3 3 13 Thotada 0.55 0.06 0.06 3 3 3 14 jammu 0.15 0.01 0.01 1 1 1 15 Gottipalle 0.25 0.02 0.02 1 1 1 16 Narasannapeta 329.42 149.11 17.88 9939 2108 237 17 Boddam 0.14 0.03 0.03 1 1 1 18 Ragolu 0.22 0.02 0.02 1 1 1 19 Patrunivalasa 0.70 0.11 0.11 5 5 5 20 Peddapadu 0.20 0.02 0.02 1 1 1 21 Pathasrikakulam 3.58 0.29 0.29 13 13 13 22 Balaga(Rural) 2.44 0.21 0.21 10 10 10 23 Arsavilli(Rural) 2.51 0.19 0.19 9 9 9 24 Ponduru 0.32 0.02 0.02 1 1 1 25 Jagannadharaja Puram 0.50 0.08 0.08 4 4 4 26 Ranastalam 0.15 0.02 0.02 1 1 1 27 Tekkali 0.15 0.02 0.02 1 1 1 28 Shermahammadpuram 0.95 0.12 0.12 6 6 6 29 Pudivalasa 0.27 0.02 0.02 1 1 1 30 Kusalapuram 2.23 0.16 0.16 7 7 7 31 Thotapalem 0.79 0.10 0.10 4 4 4 32 Etcherla 227.17 121.97 25.56 8130 3904 276 33 Yegulavada 0.32 0.05 0.05 2 2 2 34 Kurupam 109.03 49.32 -

Issn: 2278-6236 Multi Dimension Strategy for the Development of the Hyderabad Karnataka Region Introduction

` International Journal of Advanced Research in ISSN: 2278-6236 Management and Social Sciences Impact Factor: 6.284 MULTI DIMENSION STRATEGY FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE HYDERABAD KARNATAKA REGION Dr. Ravindranath N. Kadam, Associate Professor, Dept. of Studies & Research in Economics, Kuvempu University, Shankaraghatta, Shivamogga Dist, Karnataka State, India Abstract: The sub continent, India has diversity in many respects. No doubt all the states in the country are not even in all respects. No all regions are similar and equally developed. The different Finance Commissions and the Planning commission laid stress on the objective of achieving evenhanded regional development. In Karnataka state also all the regions are not equally treated and developed. It is quite essential to maintain the equality in most of the aspects. Recently the government of Karnataka has opened eyes and showing interest in the development of backward regions of Karnataka. The development of Hyderabad Karnataka (Gulbarga Division) is to be achieved on priority base as it has been neglected by the earlier rulers (Hyderabad Nizam). The present Hyderabad Karnataka region includes Bellary, Bidar, Gulbarga, Koppal and Raichur districts. The Hyderabad Karnataka region is situated in the North-Eastern part of Karnataka and bonded with Maharashtra on the North and Andhra Pradesh on the East and South. The climate of the Hyderabad Karnataka region comprised with dryness for the major part of the year and has very hot summer and scanty rain fall. In this paper attempt is made to highlight the resources available in the Hyderabad Karnataka region and the new avenues possible for the development of the region. -

Religion, Part IV-B (Ii), Series11

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES-I 1 KARNATAKA PART IV-B (ii) RELIGION (TABLE C-9) DIRECTOR OF aNSUS OPERATIONS, KARNATAKA CONTENTS Paces PREFACE v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT vII INTRODUCTORY NOTE 1. .:.Jote on RellK10n Table 15 Table C-9 : RellKIon 18 APPENDIC~ APPENDIX-A Details of religion shown under 'Other Religions and Persuasions' having population of 100 or more at the state level In main ·rellglon table. 169 APPENDIX-B Detalls of rellafon shown under 'Other Religions and Persuasions' the strenath of which Is less than 100 at the State lev~1 In the main religion table. 172 ANNEXURE Details of Sects/BeUefs/RelJafons dubbed with another rellgfon which Is shown at the head of the table In block letters. 177 PREFACE The 1991 Census of Population was conducted In February-March 1991, with the sunrise of 1st March, 1991 as the reference point of time. Extensive ubulatlon of the data collected In the Census has been undertaken by the Census Organisation and the tabulated data In the form of tables under different Series depicting various characteristics of the population are being made available to data users through a number of publications according to the Tabulation Plan of the 1991 Census. In this volume, Table C-9 : Religion which gives the distribution of population by sex and by rural and urban residence for the six maJor religious communities viz., Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists and )alns, 'Other Religions and Persuasions' and 'Religion not stated' Is presented. The returns of religions were Initially complied at the Regional Tabulation Offices established to undertake the manual processing of the census schedules and for attending to few basic compilations on full count basis and further processing of the returns and preparation of the table were undertaken In this Directorate. -

Towns of India: Status of Demography, Economy, Social Structures, Housing and Basic Infrastructure

Towns of India Status of Demography, Economy, Social Structures, Housing and Basic Infrastructure HSMI – HUDCO Chair – NIUA Collaborative Research 2016 Towns of India Status of Demography, Economy, Social Structures, Housing and Basic Infrastructure HSMI – HUDCO Chair – NIUA Collaborative Research 2016 Foreword An increasing number of people live in small and medium-sized towns in the periphery of large cities as the world completes its process of urban transition. India is no exception to this phenomenon. It is in these towns where national economies are to be built, solutions to global challenges such as inequality and the impacts of climate change are to be addressed, and future generations are to be educated. The reality in India, however, suggests that the small towns are not fully integrated in the urban fabric of the nation. They have enormous backlogs in economic infrastructure, weak human capacity, high levels of under unemployment and unemployment, and extremely weak local economies. However, with their growing numbers – there are more than 2,500 new towns added in the last Population Census– the role of small and medium-sized towns in the national economy will have a significant influence upon the future social and economic development of larger geographic regions. If these towns were better equipped to steer their economic assets and development, the national Gross Domestic Product (GDP) could be increased, with significant benefits reducing rural poverty in the hinterlands. This research on small towns, those below 100,000 population, was conducted at the National Institute of Urban Affairs (NIUA), New Delhi, under Phase III of the HUDCO Chair project during the period 2015-16. -

D-Dip0000000619

GOVERMENT OF KARNATAKA DISTRICT IRRIGATION PLAN UNDER PRADHAN MANTRI KRISHI SINCHAYEE YOJANA (PMKSY) Department of Agriculture & Department of Irrigation & CAD RAICHUR DISTRICT (KARNATAKA STATE) CONTENTS SL.NO. CHAPTER DESCRIPTION PAGE NO 1 I Executive summary 2 i Background 3 ii Vision 4 iii Objectives 5 iv Strategy/ approach 6 v Justification statement 7 1 General Information of the District 8 2 District Water Profile 9 3 Water Availability 10 4 Water requirement/Demand 11 5 Strategic action plan for Irrigation Under PMKSY LIST OF TABLES SL.NO. TABLE DETAILS PAGE NO. 1 Table - 1.1 District Profile 2 Table - 1.1a Taluka wise Area and number of Villages and Population 3 Table - 1.2 Taluk wise demography details 4 Table - 1.3 Biomass and Livestock of the District 5 Table - 1.4 a Taluka wise Seasonal and Annual normal rainfall in Raichur District from 2001 -14 6 Table - 1.4 b Data on Climatic parameters 7 Table - 1.4 c Taluka wise Normal rainfall in Raichur District 8 Table - 1.4 d Agro Ecology, Climate, Hydrology and Topography of Raichur taluk 9 Table - 1.4 e Agro Ecology, Climate, Hydrology and Topography of Manvi taluk 10 Table - 1.4 f Agro Ecology, Climate, Hydrology and Topography of Devadurga taluk 11 Table - 1.4 g Agro Ecology, Climate, Hydrology and Topography of Lingasugur taluk 12 Table - 1.4 h Agro Ecology, Climate, Hydrology and Topography of Sindhanur taluk 13 Table - 1.5 Soil profile 14 Table - 1.6 Soil erosion and run off status 15 Table - 1.7 I Taluk wise land utilization in Raichur district (in sq.km) 16 Table - 1.7 II -

Kind Attention to DDPUE's Furnish Longitude and Latitude Details

SL_NO CODE COLL_NM ADDR1 ADDR2 FLAG UDISE LONGITUDE LATITUDE 1 AN011 MOUNT CARMEL PU COLLEGE 58 PALACE RD VASANTHNAGAR BANGALORE 560052 F 29280602440 2 AN012 MES PU COLLEGE MALLESWARAM 15TH CROSS BANGALORE 560003 F 29200906969 3 AN014 GOVT PU COLLEGE FOR BOYS MALLESWARAM 18TH CROSS BANGALORE 560012 G 29280502011 4 AN015 MLA PU COLLEGE FOR WOMEN MALLESWARAM 15TH CROSS BANGALORE A 29280500795 5 AN020 S NIJALINGAPPA BFR PU COL RAJAJINAGAR II BLOCK BANGALORE 560010 F 29280200437 6 AN022 BASAVESHWARA PU COLLEGE RAJAJINAGAR II BLOCK BANGALORE 560010 A 29280200439 7 AN023 SJRC BIFR PU COLLEGE BANGALORE BANGALORE 560009 F 29280500862 8 AN025 ST JOSEPH'S PU COLLEGE RESIDENCY ROAD PBNO 25003 BANGALORE 560025 F 511022158 9 AN028 ST JOSEPH EVENING PU COLL 35 MUSEUM ROAD PBNO 25003 BANGALORE 560025 F 29280600728 10 AN041 SESHADRIPURAM IND PU COL SESHADRIPURAM BANGALORE 560020 A 29280500858 11 AN042 VIVEKANANDA PU COLLEGE BANGALORE CITY BANGALORE DISTRICT A 29280200445 12 AN043 SESHADRIPURAM EVEN PU COL NAGAPPA ST SESHADRIPURAM BANGALORE 560020 U 29280500867 13 AN046 RBANM'S PU COLLEGE 12/A ANNASWAMY MUDALIAR ROAD BANGALORE 560042 A 29280601368 14 AN047 HASANATH PU COL FOR WOMEN DICKENSON ROAD BANGALORE 560042 A 29280601367 15 AN051 ST ALOYSIUS PU COLLEGE COX TOWN BANGALORE 560005 A 29280600829 16 AN054 VVS PU COLLEGE RAJAJINAGAR I BLOCK BANGALORE 560010 A 29280208858 17 AN057 VEERENDRAPATIL PU COLLEGE SADASHIVANAGAR 11 MN RMV BANGALORE 560080 F 29280502014 18 AN059 RBANMS EVENING PU COLLEGE NO 24 GANGADHARCHETTY RD BANGALORE 560042 U 29280601434 19