Le<Ii:ND of Tile LFI'i R Kinci

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inventaire-CIK-09042017.Pdf

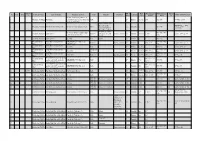

Autre(s) Nb de Date Estampages Estampages Autres K. Ext. Ind. Pays, province Lieu d’origine Situation actuelle Type Détails Matériau Langue Éditions/traductions n° lignes (śaka) EFEO BNF est. In situ ; dans la maçonnerie de 1 - - - Vietnam, An Giang Vat Thling l’autel de la pagode du village de Stèle 26 Khmer vie-viie 271 302 (34) - IC VI, p. 28-30 Lê Hoat, Châu Đốc Dalle formant seuil du tombeau du BEFEO XL, p. 480 2 - - - Vietnam, An Giang Phnom Svam ou Nui Sam In situ (en 1923, Cœdès 1923) Dalle 12 Sanskrit xe - 301 (34) - mandarin Nguyên (chronique) Ngoc Thoai ; Ruinée Trouvée sur l'allée In situ (en 2002), enchassé dans 303 (34) ; 471 3 - - - Vietnam, An Giang Linh Son Tu Piédroit principale de Linh Schiste ardoisier 11 Sanskrit vie-viie n. 295 - Cœdès 1936, p. 7-9 l'autel de Linh Son Tu (79) Son Tu 4 - - - Vietnam, An Giang Linh Son Tu Inconnue Stèle Ruinée 12 Khmer xe - 304 (34) - - Vietnam, Đồng Thap Muoi, Prasat Pram BTLSHCM 2893 (Kp 1, 2) ; 305 (69) ; 472 5 - - - Piédroit Schiste ardoisier 22 Sanskrit ve 329 ; n. 15 - Cœdès 1931, p. 1-7 Tháp Loveng BTLS 5964? (79) Vietnam, Đồng Thap Muoi, Prasat Pram 6 - - - Inconnue Stèle 10 Khmer vie-viie - 306 (34) - Cœdès 1936, p. 5 Tháp Loveng Vietnam, Đồng Thap Muoi, Prasat Pram Chapiteau 307 (34) ; 473 7 - - - Inconnue 20 Khmer vie-viie 331 ; n. 16 - Cœdès 1936, p. 3-5 Tháp Loveng (?) (79) Vietnam, Đồng Thap Muoi, Prasat Pram 308 (34) ; 474 8 - - - DCA 6811 Piédroit Schiste ardoisier 10 Khmer vie-viie 259 ; n. -

Cambodia-10-Contents.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Cambodia Temples of Angkor p129 ^# ^# Siem Reap p93 Northwestern Eastern Cambodia Cambodia p270 p228 #_ Phnom Penh p36 South Coast p172 THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Nick Ray, Jessica Lee PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Cambodia . 4 PHNOM PENH . 36 TEMPLES OF Cambodia Map . 6 Sights . 40 ANGKOR . 129 Cambodia’s Top 10 . 8 Activities . 50 Angkor Wat . 144 Need to Know . 14 Courses . 55 Angkor Thom . 148 Bayon 149 If You Like… . 16 Tours . 55 .. Sleeping . 56 Baphuon 154 Month by Month . 18 . Eating . 62 Royal Enclosure & Itineraries . 20 Drinking & Nightlife . 73 Phimeanakas . 154 Off the Beaten Track . 26 Entertainment . 76 Preah Palilay . 154 Outdoor Adventures . 28 Shopping . 78 Tep Pranam . 155 Preah Pithu 155 Regions at a Glance . 33 Around Phnom Penh . 88 . Koh Dach 88 Terrace of the . Leper King 155 Udong 88 . Terrace of Elephants 155 Tonlé Bati 90 . .. Kleangs & Prasat Phnom Tamao Wildlife Suor Prat 155 Rescue Centre . 90 . Around Angkor Thom . 156 Phnom Chisor 91 . Baksei Chamkrong 156 . CHRISTOPHER GROENHOUT / GETTY IMAGES © IMAGES GETTY / GROENHOUT CHRISTOPHER Kirirom National Park . 91 Phnom Bakheng. 156 SIEM REAP . 93 Chau Say Tevoda . 157 Thommanon 157 Sights . 95 . Spean Thmor 157 Activities . 99 .. Ta Keo 158 Courses . 101 . Ta Nei 158 Tours . 102 . Ta Prohm 158 Sleeping . 103 . Banteay Kdei Eating . 107 & Sra Srang . 159 Drinking & Nightlife . 115 Prasat Kravan . 159 PSAR THMEI P79, Entertainment . 117. Preah Khan 160 PHNOM PENH . Shopping . 118 Preah Neak Poan . 161 Around Siem Reap . 124 Ta Som 162 . TIM HUGHES / GETTY IMAGES © IMAGES GETTY / HUGHES TIM Banteay Srei District . -

Temples Tour Final Lite

explore the ancient city of angkor Visiting the Angkor temples is of course a must. Whether you choose a Grand Circle tour or a lessdemanding visit, you will be treated to an unforgettable opportunity to witness the wonders of ancient Cambodian art and culture and to ponder the reasons for the rise and fall of this great Southeast Asian civili- zation. We have carefully created twelve itinearies to explore the wonders of Siem Reap Province including the must-do and also less famous but yet fascinating monuments and sites. + See the interactive map online : http://angkor.com.kh/ interactive-map/ 1. small circuit TOUR The “small tour” is a circuit to see the major tem- ples of the Ancient City of Angkor such as Angkor Wat, Ta Prohm and Bayon. We recommend you to be escorted by a tour guide to discover the story of this mysterious and fascinating civilization. For the most courageous, you can wake up early (depar- ture at 4:45am from the hotel) to see the sunrise. (It worth it!) Monuments & sites to visit MORNING: Prasats Kravan, Banteay Kdei, Ta Prohm, Takeo AFTERNOON: Prasats Elephant and Leper King Ter- race, Baphuon, Bayon, Angkor Thom South Gate, Angkor Wat Angkor Wat Banteay Srei 2. Grand circuit TOUR 3. phnom kulen The “grand tour” is also a circuit in the main Angkor The Phnom Kulen mountain range is located 48 km area but you will see further temples like Preah northwards from Angkor Wat. Its name means Khan, Preah Neak Pean to the Eastern Mebon and ‘mountain of the lychees’. -

Discover Cambodia

(650) 223-5520 ◆ [email protected] ◆ CST 2130343-40 TRAVELLING TO NEW PLACES WITH CONFIDENCE Discover Cambodia 6-Day, 5-Night Journey Siem Reap This 6-day journey explores the history and archaeological sites of a dynasty from Khmer kings who once ruled one of the largest, most prosperous, and most sophisticated kingdoms in the history of Southeast Asia. In Cambodia, ancient and modern worlds collide to create an authentic adventure to remember. Explore the temples of Angkor and be amazed by one of the world’s greatest architectural showpieces! Be inspired with a comprehensive look into the ancient Khmer culture and how the people here are determined to preserve its history and traditions while welcoming modern development. This trip is perfect for those wanting to take in all the main highlights of this fascinating country! ✦ Customizable Private Tour Trip Overview (*UNESCO World Heritage Sites) ‣ Shrine of Two Angkorian ‣ Terrace of the Elephants ‣ Ruins of Ta Prohm Princesses: Preah Ang Chek ‣ Terrace of the Leper King ‣ Royal City of Preah Khan & Preah Angkor Chom ‣ Angkor Wat ‣ Neak Pean ‣ Pagoda ‣ Morning Alms ‣ Ta Som ‣ Angkor Archaeological Park* ..(Food Offerings to Monks) ‣ East Mebon ‣ Angkor Thom ‣ Live Cooking Class & Lunch ‣ Preah Rup ‣ Baphuon Temple ‣ Apsara Dance Performance As of April 5, 2020 | Page: 1 ‣ Thommanon Temple ‣ Prasat Kravan(Brick Sculptures) ‣ Village Visit ‣ Ta Keo ‣ Les Chantiers Ecole ‣ Baray Oriental sites ‣ Banteay Kdei (Handicraft Center) ‣ Monastery (Citadel of the Cells) ‣ Banteay Srei Temple ‣ Tonle Sap Lake Floating Village ‣ Srah Srang (Royal Bathing Place) ‣ Kbal Spean Archaeological Site & Boat Ride Why You’ll Love This Tour AN EMPIRE OF TEMPLES The Khmer Empire was the largest empire of Southeast Asia and flourished between the 9th and 15th century. -

Phnom Penh 42 Destination Siem Reap

Sky Angkor Airlines Your In-Flight Magazine Issue #06 Welcome to Sky Angkor Airlines! ក䮚ុមហ៊ុន Sky Angkor Airlines សូមស䮜គមន៍!䮚 We’re delighted to have you on board. យើង掶នក䮏ី翄មនស្សដល厶ន濄ក-អ䮓កធ䮜ើដំណើរᾶមួយក្ ុមហ៊ុនយើងខ䮉ុំ្ ។ Our growing fleet of A320s and A321s are flying to more យើងខ䮉ុំ掶នបន䮐មប្ ភ្ ទយន្ ោះល䮏 ខ្ A320 និង A321 ដលកំពុងដំណើរζរ្ destinations to offer you greater travel choices and opportunities, ោះហើរ䟅ζន់ល⯅ᾶច្ើន សម្្ប់ᾶជម្ើស និងឱζសζន់ត្ប្សើរ foremost of which are routes linking Cambodia to China. From ᾶងនះជូន濄ក-អ䮓ក្ ហើយជើងោះហើរមុនគបង䮢ស់របស់ក្ ុមហ៊ុនយើងខ䮉ុំ្ នឹងភ䮇ប់្ Siem Reap, we now operate to a wealth of Chinese destinations ជើងោះហើរពីពះ殶ᾶ㮶ចក្ កម䮖្ ុជា ζន់បទ្ សចិន្ ។ សព䮜ថ䮄ន្ ះ្ យើងខ䮉ុំ掶ន including Chengdu, Wuhan, Beijing, Tianjin, Wuxi, Nanning, ភ䮇ប់ζរ្ ោះហើរពីខត䮏សៀម殶ប្ 䟅ខត䮏ឆឹងទូ្ អ៊ូ莶ន ទីកុងប៉្ ζំង្ 䮶នជីន អ៊ូស្សី ុ Shanghai, Hefei, Zhengzhou, Nanjing, Guiyang, Nanchang, 㮶ននីង ស៊ងហ្ ្ ហឺហ䮜ី ហ្សិងចូវ 㮶នជីង ហ䮂ីយ៉ង្ 㮶នាង 厶វទូ ⮶ថុង និងសអ៊ូល្ Baotou, and Datong, as well as Seoul in South Korea. And from ស䮶រណរដ䮋កូរ៉្ងត្បូងផងដ្រ។ បន䮐្មពីន្ះ យើង厶នភ䮇្ប់ζរោះហើរពីឆឹងទូ Sihanoukville, we operate to Chengdu, Wuhan, Tianjin, and Wuxi. អ៊ូ莶ន 䮶នជីង និងអ៊ូស្សុី មកζន់ខ្ត䮏ព្ះសីហនុ។ This time of year is arguably the best to visit Cambodia, with រដូវζលន្ះគឺᾶព្លវ្澶ដ៏ល䮢បំផុត ដើម្បីមកទស្ស侶ប្ទ្សកម䮖ុᾶ ព្្ះ the rains from the wet season starting to subside and cool, រដូវវស្羶厶នកន䮛ងផុត䟅 讶ζស䮶តុក៏ប្្ᾶស䮄ួត និងត្ᾶក់ល䮘មសម្្ប់ភ䮉ៀវ dry weather affording ideal touring conditions, especially out ទសចរណ៍្ ᾶពិសស្ 俅㾶មទីជនបទពណ៌បតង្ ។ ដូច䮓ះហើយ្ កពីប្្ ្្សទអង䮂រ in the luscious, green countryside. So why not explore what ហ្តុអ䮜ី濄ក-អ䮓កមិនសកល្បង䟅កម្羶ន䮏俅 សហគមន៍ទ្សចរណ៍ផ្ស្ងទៀតក䮓ុង Siem Reap province has to offer other than its magnificent ខត䮏សៀម殶ប?្ សូមស䮜ងយល់បន䮐្ មពីតំបន់ទ្ សចរណ៍ស្ ស់ស䮢្ ត䞶ំង俄ះ្ 俅ក䮓ុង Angkor temples with a community-based tour. -

Towards a Christian Pastoral Approach to Cambodian Culture

Thesis Title: Towards a Christian Pastoral Approach to Cambodian Culture In fulfilment of the requirements of Master’s in Theology (Missiology) Submitted by: Gerard G. Ravasco Supervised by: Dr. Bill Domeris, Ph D March, 2004 Towards a Christian Pastoral Approach to Cambodian Culture Table of Contents Page Chapter 1 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 The world we live in 1 1.2 The particular world we live in 1 1.3 Our target location: Cambodia 2 1.4 Our Particular Challenge: Cambodian Culture 2 1.5 An Invitation to Inculturation 3 1.6 My Personal Context 4 1.6.1 My Objectives 4 1.6.2 My Limitations 5 1.6.3 My Methodology 5 Chapter 2 2.0 Religious Influences in Early Cambodian History 6 2.1 The Beginnings of a People 6 2.2 Early Cambodian Kingdoms 7 2.3 Funan 8 2.4 Zhen-la 10 2.5 The Founding of Angkor 12 2.6 Angkorean Kingship 15 2.7 Theravada Buddhism and the Post Angkorean Crisis 18 2.8 An Overview of Christianity 19 2.9 Conclusion 20 Chapter 3 3.0 Religions that influenced Cambodian Culture 22 3.1 Animism 22 3.1.1 Animism as a Philosophical Theory 22 3.1.2 Animism as an Anthropological Theory 23 3.1.2.1 Tylor’s Theory 23 3.1.2.2 Counter Theories 24 3.1.2.3 An Animistic World View 24 3.1.2.4 Ancestor Veneration 25 3.1.2.5 Shamanism 26 3.1.3 Animism in Cambodian Culture 27 3.1.3.1 Spirits reside with us 27 3.1.3.2 Spirits intervene in daily life 28 3.1.3.3 Spirit’s power outside Cambodia 29 3.2 Brahmanism 30 3.2.1 Brahmanism and Hinduism 30 3.2.2 Brahmin Texts 31 3.2.3 Early Brahmanism or Vedism 32 3.2.4 Popular Brahmanism 33 3.2.5 Pantheistic Brahmanism -

Appendix Appendix

APPENDIX APPENDIX DYNASTIC LISTS, WITH GOVERNORS AND GOVERNORS-GENERAL Burma and Arakan: A. Rulers of Pagan before 1044 B. The Pagan dynasty, 1044-1287 C. Myinsaing and Pinya, 1298-1364 D. Sagaing, 1315-64 E. Ava, 1364-1555 F. The Toungoo dynasty, 1486-1752 G. The Alaungpaya or Konbaung dynasty, 1752- 1885 H. Mon rulers of Hanthawaddy (Pegu) I. Arakan Cambodia: A. Funan B. Chenla C. The Angkor monarchy D. The post-Angkor period Champa: A. Linyi B. Champa Indonesia and Malaya: A. Java, Pre-Muslim period B. Java, Muslim period C. Malacca D. Acheh (Achin) E. Governors-General of the Netherlands East Indies Tai Dynasties: A. Sukhot'ai B. Ayut'ia C. Bangkok D. Muong Swa E. Lang Chang F. Vien Chang (Vientiane) G. Luang Prabang 954 APPENDIX 955 Vietnam: A. The Hong-Bang, 2879-258 B.c. B. The Thuc, 257-208 B.C. C. The Trieu, 207-I I I B.C. D. The Earlier Li, A.D. 544-602 E. The Ngo, 939-54 F. The Dinh, 968-79 G. The Earlier Le, 980-I009 H. The Later Li, I009-I225 I. The Tran, 1225-I400 J. The Ho, I400-I407 K. The restored Tran, I407-I8 L. The Later Le, I4I8-I8o4 M. The Mac, I527-I677 N. The Trinh, I539-I787 0. The Tay-Son, I778-I8o2 P. The Nguyen Q. Governors and governors-general of French Indo China APPENDIX DYNASTIC LISTS BURMA AND ARAKAN A. RULERS OF PAGAN BEFORE IOH (According to the Burmese chronicles) dat~ of accusion 1. Pyusawti 167 2. Timinyi, son of I 242 3· Yimminpaik, son of 2 299 4· Paikthili, son of 3 . -

Reclamation and Regeneration of the Ancient Baray

RECLAMATION AND REGENERATION OF THE ANCIENT BARAY A Proposal for Phimai Historical Park Olmtong Ektanitphong December 2014 Submitted towards the fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Architecture Degree. School of Architecture University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Doctorate Project Committee Kazi K. Ashraf, Chairperson William R. Chapman, Committee Member Pornthum Thumwimol, Committee Member ACKNOWLEDMENTS I would like to express the deepest appreciation to my committee chair, Professor Kazi K. Ashraf, who has the attitude and the substance of a genius: he continually and convincingly a spirit of adventure in regard to research and the design, and excitement in regard to teaching. Without his guidance and persistent help this dissertation would not have been possible. I would like to thank my committee members, Professor William R. Chapman and Dr. Pornthum Thumwimol, whose work demonstrated to me that concern for archaeological aspects of Khmer and Thai culture. They supported me immensely throughout the period of my dissertation. Their valuable advice and discussions guided me to the end-result of this study. I highly appreciated for their generally being a good uncle and brother as well as a supervisor. In addition, a thank you to the director, archaeologists, academic officers and administration staff at Phimai Historical Park and at the Fine Arts Department of Thailand, who gave me such valuable information and discussion. Specially, thank you to Mr. Teerachat veerayuttanond, my supervisor during internship with The Fine Arts Department of Thailand, who first introduced me to Phimai Town and took me on the site survey at Phimai Town. Last but not least, I would like to thank University of Hawaii for giving me the opportunity for my study research and design. -

A STUDY of the NAMES of MONUMENTS in ANGKOR (Cambodia)

A STUDY OF THE NAMES OF MONUMENTS IN ANGKOR (Cambodia) NHIM Sotheavin Sophia Asia Center for Research and Human Development, Sophia University Introduction This article aims at clarifying the concept of Khmer culture by specifically explaining the meanings of the names of the monuments in Angkor, names that have existed within the Khmer cultural community.1 Many works on Angkor history have been researched in different fields, such as the evolution of arts and architecture, through a systematic analysis of monuments and archaeological excavation analysis, and the most crucial are based on Cambodian epigraphy. My work however is meant to shed light on Angkor cultural history by studying the names of the monuments, and I intend to do so by searching for the original names that are found in ancient and middle period inscriptions, as well as those appearing in the oral tradition. This study also seeks to undertake a thorough verification of the condition and shape of the monuments, as well as the mode of affixation of names for them by the local inhabitants. I also wish to focus on certain crucial errors, as well as the insufficiency of earlier studies on the subject. To begin with, the books written in foreign languages often have mistakes in the vocabulary involved in the etymology of Khmer temples. Some researchers are not very familiar with the Khmer language, and besides, they might not have visited the site very often, or possibly also they did not pay too much attention to the oral tradition related to these ruins, a tradition that might be known to the village elders. -

Figs. 7, 46 Pls. 15,16 Fig. 52 Fig. Figs. Fig. 24 Figs. 8, 12, Fig. 33

INDEX Ak Yorn, Prasat XIX, XXIl,46, 55 Borobudur, Java XXI, 27, 45, 46, 49, Anavatapa, lake 94 50, 51 Fig. 44 Andet, Prasat 44 Boulbet,Jean. 46 Andon, Prasat see Neak Ta Brahma 7 Angkor XIX, XXIII, XXVIII, 4, 5, 14, 20, 23, 24,44,48,50,54,55,62, Cakravartin 111 63, 64, 68, 72, 76, 78, 79, 81, 90, Ceylon 16, 17 96, 97, 98, 109, 110 Chaiya, Thailand 45 Angkor Thom 59, 81, 90, 94, 98, 99, Cham XXV, XXVII, 28, 45, 90, 99 105, 106, 107, 111 Chau Say Tevoda 30, 81, 90, 97 Angkor Wat XXIV, XXV, XXVI, Chola, dynasty 28 XXVII, XXVIII, XXIX, 4, 8, 12, Chou Ta-kuan (Zhou Daguan) 29, 79, 24, 26, 30, 31, 74, 78, 80, 83-89, 87, 101, 112 91, 98, 99, 100, 109, 111, 112 Chrei, Prasat 82, 90 Fig. 25 Figs. 28, 78,79 Pls. 31-33 Coedes, George 6, 18, 19, 22, 83 Argensola, d' XXVIII Aymonier, Etienne XXVIII Dagens, Bruno XXIII, 18, 46, 93 Damrei Krap, Prasat 28, 45, 4 7 Figs. Bakong XXI, 4, 11, 45, 50, 51, 53, 54, 43, 45 Pl. 14 55, 59, 65. Figs. 7, 46 Pls. 15,16 Dhrannindravarman I, King 7 Bakasei Chamkrong 29, 34, 54, 60, 63, Dieng, Java XVII, XX 66, 106. Fig. 52 Do Couto, Diego XXXVIII Baluchistan XVIII. Bantay Chmar XXVI, XXVII, 5, 12, 96, Elephant Terrace 78 Fig. 21 99. Bantay Kdei 28, 96, 98, 100. Bantay Samre 24. Filliozat, Jean 21 Bantay Srei 11, 15, 66-67, 69, 72 Fig. -

Report of the Ad Hoc Group of Experts on Behalf of the International

KH/CLT/2005/RP/10 Phnom Penh, July 2008 Original: English Comité International de Coordination pour la Sauvegarde et le Développement du Site Historique d'Angkor International Co-ordinating Committee for the Safeguarding and Development of the Historic Site of Angkor Session Plénière Plenary Session co-présidé par / co-chaired by M./Mr. Yvon Roé D’Albert M./Mr. Fumiaki Takahashi Ambassadeur Extraordinaire et Plénipotentiaire Ambassadeur Extraordinaire et Plénipotentiaire Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Ambassade de France Ambassade du Japon Embassy of France Embassy of Japan Siem Reap – Novembre 28 & 29, 2005 – Hôtel Angkor Palace Resort & Spa Siem Reap – November 28 & 29, 2005 – Angkor Palace Resort & Spa Hotel Secrétariat permanent du C.I.C. Angkor #38 Bld Samdech Sothearos, B.P. 29, UNESCO Phnom Penh, Cambodge Tél.: (855-23) 723 054 / 426 726 Fax (855-23) 426 163 / 217 022 Mél.: [email protected] [email protected] Douzième Session Plénière / Twelfth Plenary Session 1/152 STANDING SECRETARIAT • UNESCO Office Address : 38, blvd Samdech Sothearos BP 29 Phnom Penh Cambodia Tel.: (855) (23) 426 726 (855) (23) 723 054 / 725 071 (855) (12) 911 651 (855) (16) 831 520 (855) (12) 813 844 (855) (23) 720 841 Fax: (855) (23) 426 163 / 217 022 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] • Standing Secretariat in Paris Mr. Azedine BESCHAOUCH Scientific Advisor of the Sector of Culture in Phnom Penh Mr Blaise KILIAN Ms CHAU SUN Kérya (APSARA Authority) Mr. -

Medieval Khmer Society: the Life and Times of Jayavarman VII (Ca

John Carroll University Carroll Collected 2019 Faculty Bibliography Faculty Bibliographies Community Homepage 2019 Medieval Khmer Society: The Life and Times of Jayavarman VII (ca. 1120–1218) Paul K. Nietupski John Carroll University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://collected.jcu.edu/fac_bib_2019 Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons, East Asian Languages and Societies Commons, and the Hindu Studies Commons Recommended Citation Nietupski, Paul K., "Medieval Khmer Society: The Life and Times of Jayavarman VII (ca. 1120–1218)" (2019). 2019 Faculty Bibliography. 34. https://collected.jcu.edu/fac_bib_2019/34 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Bibliographies Community Homepage at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2019 Faculty Bibliography by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Article How to Cite: Nietupski, Paul. 2019. Medieval Khmer Society: The Life and Times of Jayavarman VII (ca. 1120–1218). ASIANetwork Exchange, 26(1), pp. 33–74. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/ane.280 Published: 19 June 2019 Peer Review: This article has been peer reviewed through the double-blind process of ASIANetwork Exchange, which is a journal of the Open Library of Humanities. Copyright: © 2019 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Open Access: ASIANetwork Exchange is a peer-reviewed open access journal.