The Works of Anthony Trollope, Joseph Conrad, E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flashback: Satyajit Ray's Professor Shonku and His Lost

TALKING FILMS Flashback: Satyajit Ray’s Professor Shonku and his lost project ‘The Alien’ All about the screenplay that reportedly inspired Steven Spielberg’s ‘E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial’. Chandrima Pal Mar 09, 2018 · 09:15 am Satyajit Ray’s alien Bengali director Sandip Ray’s latest movie features one of Satyajit Ray’s best-known literary creations. Not the detective Feluda, but Professor Shonku, the scientist and eccentric genius who was introduced by Sandip Ray’s father in 1961. Sandip Ray’s Professor Shonku O El Dorado is based on the story Nakur Babu O El Dorado, in which Shonku takes off on an adventure with a man who can see into the future and make people see things that are not immediately visible. Produced by leading Kolkata studio SVF, the movie will be shot in Bengal and Brazil, and is aiming for a release later this year. Shonku, to be played by thespian Dhritiman Chatterjee, has never been filmed before, unlike Feluda, about whom several movies and television serials have been made. Inspired partly by Arthur Conan Doyle’s Professor Challenger and Hesoram Hushiar, a character created by Ray’s father Sukumar Ray, Shonku is every bit as fascinating as Feluda. He is a polyglot (he knows 69 languages), graduated from college at the age of 16, and started teaching when he was 20. Shonku works out of a laboratory at home where he uses locally available ingredients for his groundbreaking inventions. He keeps a low profile and refuses to share his formulas or inventions because he doesn’t want them to fall into the wrong hands. -

The Writing in Goopy Bagha

International Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies (IJHCS) ISSN 2356-5926 Vol.1, Issue.2, September, 2014 Right(ing) the Writing: An Exploration of Satyajit Ray’s Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne Amrita Basu Haldia Institute of Technology, Haldia, West Bengal, India Abstract The act of writing, owing to the permanence it craves, may be said to be in continuous interaction with the temporal flow of time. It continues to stimulate questions and open up avenues for discussion. Writing people, events and relationships into existence is a way of negotiating with the illusory. But writing falters. This paper attempts a reading of Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne in terms of power politics through the lens of the manipulation of written codes and inscriptions in the film. Identities and cultures are constructed through inscriptions and writings. But in the wrong hands, this medium of communication which has the potential to bring people together may wreck havoc on the social and political system. Writing, or the misuse of it, in the case of the film, reveals the nature of reality as provisional. If writing gives a seal of authenticity to a message, it can also become the casualty of its own creation. Key words: Inscription, Power, Politics, Writing, Social system 1 International Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies (IJHCS) ISSN 2356-5926 Vol.1, Issue.2, September, 2014 Introduction Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne by Satyajit Ray is a fun film for children of all ages; it ran to packed houses in West Bengal for a record 51 weeks and is considered one of the most commercially successful Ray films. -

The Humanism of Satyajit Ray, His Last Will and Testament Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri

AGANTUK – The Humanism of Satyajit Ray, His Last Will And Testament Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri It’s impossible to record the transition in the socio-political and cultural landscape of India in general and Bengal in particular without taking into account the contribution of Satyajit Ray. As author Peter Rainer says, ‘In Ray’s films the old and the new are inextricably joined. This is the great theme of all his movies: the way the past in India forever bleeds through the present.’ Today, Indian cinema, particularly Bollywood, has found a global market. But it may be useful to remember that if anyone can be credited with putting Indian cinema on the world map, it is Satyajit Ray. He pioneered a whole new sensibility about films and filmmaking that compelled the world to reshape its perception of Indian cinema. ‘What we need,’ he wrote in 1947, before he ever directed a film, ‘is a style, an idiom, a part of the iconography of cinema which would be uniquely and recognizably Indian.’ This Still from the documentary, The Music of Satyajit Ray he achieved, and yet, like all great artists, his films went Watch film here- https://bit.ly/3u8orOD beyond the frontiers of countries and cultures. His contribution to the cultural scene in India is limited not just to his work as a director. He was the Renaissance man of independent India. As a film-maker he handled almost all the departments on his own – he wrote the screenplay and dialogues for his film, he composed his own music, designed the promotional material for his films, designed his own posters, went on to handle the cinematography and editing, was actively involved in the costumes (literally sketching each and every costume in a film). -

Issn 2454-8596

ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Modernisation of Myth in Amish Tripathi's Shiva Trilogy and Ram Chandra Series Priti M. Padsumbiya Dr Ankit Gandhi Research Scholar Assistant Professor Dept. of English Dept. of English Madhav University, Sirohi, Rajasthan Madhav University, Sirohi, Rajasthan V o l u m e . 3 I s s u e 4 F e b r u a r y - 2 0 1 8 Page 1 ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ABSTRACT Each extraordinary human civilization has its own fortune of folklore. Egypt, Rome, Greece, India, China and different societies are the exemplary models. Every one of them, throughout history, made old stories, network customs and social convictions which prompted the making of tremendous collections of mythology. India has most likely the most extravagant storage facility of folklore and legends on the planet. It is encouraged from incalculable sources and safeguarded in the four Vedas , the Upanishads, the two stories, the eighteen fundamental Purans and manychants, plays, verse, figures ,move, music and folklore. The underlying foundations of India‟s incredible past go before the Aryans to the Dravidians and even -

Ethical Wisdom and Philosophical Judgment in Amish Tripathi's the Oath of Vayuputras

Linguistics and Literature Studies 1(1): 20-31, 2013 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2013.010104 Ethical Wisdom and Philosophical Judgment in Amish Tripathi's The Oath of Vayuputras Lata Mishra Department of English Government KRG Autonomous PG Girls' College Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Copyright © 2013 Horizon Research Publishing All rights reserved. Abstract This paper considers 'culture' as a framework in of good and evil, as perceived in Indian society. The which people live their lives and communicate shared concluding novel, The Oath of Vayuputras, argues and to a meanings with each other. Culture has been a dynamic great extent convinces that the culture of the nation, that system through which a society constructs, represents, enacts ignores the Laws of Nature, violates it, while the one that and understands itself. The research documents the way follows Laws of Nature leads its nation towards human consciousness cognizes and registers the world enlightenment. For fulfilling, harmonious and progressive around her/him. 'The Shiva Trilogy" authored by Amish life one is required to live in accordance with Laws of Nature Tripathi combines the narrative excess with philosophical or Dharma. The trilogy combines the narrative excess with debate. The fiction depicts that the culture evolves as men philosophical debate. sacrifice their duty (swadharma) for the greater good, Amish recreates the myth of Shiva, Ganesh, Sati and Kali Universal Dharma. The Oath of Vayuputras, enlivens through his study of all spheres of Indian life and literature. consciousness and promotes the experience of a new sense of He makes Shiva myth appealing and intelligible to the Self. -

NEW PATHWAYS an Interactive Course in English

Revised NEW PATHWAYS An Interactive Course in English COURSEBOOK 7 GAYATRI KHANNA 3 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries. Published in India by Oxford University Press 22 Workspace, 2nd Floor, 1/22 Asaf Ali Road, New Delhi 110002, India © Oxford University Press 2012, 2016, 2020 The moral rights of the author/s have been asserted. First Edition published in 2012 Second Edition published in 2016 This New Edition published in 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. ISBN-13: 978-0-19-012152-5 ISBN-10: 0-19-012152-1 Typeset in Calibri Regular by Recto Graphics, Delhi 110096 Printed in India by Multivista Global Pvt. Ltd., Chennai 600042 Oxford Areal is a third-party software. Any links to third-party software are provided "as is" without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied, and such software is to be used at your own risk. -

Indian Scholar

ISSN 2350-109X Indian Scholar www.indianscholar.co.in An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal PORTRAYAL OF MYTHOLOGY IN AMISH TRIPATHI’S "THE IMMORTAL OF MELUHA" S. Sumathi Assistant Professor Department of English D.K.M. College for Women Vellore-1 All the literature of our world, are the outputs of the human emotions. Indian English literature is not essentially different in kind from the other Indian literatures. Its writers have made the most significant contribution in the fields of poetry, fiction, drama, short story, biography and autobiography. Indian English Literature is deeply rooted in our geographical climate and cultural beliefs. The Indian English novels were developed as a subaltern awareness; as a response to break away from the colonial literature. Hence the post-colonial Indian literature witnessed a revolution against the idiom which the colonial writers followed. However the Indian English writers started employing the techniques of mixed language, magic realism garnished with native themes. Hence from a post-colonial era Indian English literature ushered into the contemporary and then the post-modern era. The saga of the Indian English novel therefore stands as the tale of changing tradition, the story of changing India. The history of Indian English novel, a journey which began long back has witnessed a lot of alteration to gain the current stylish delineation. In the past few years many prominent writers have made a mark on the Indian Diaspora. Later, the concept of Indian English novel or rather the concept of Indians writing in English came much advanced and it is with the coming of Raja Rao, R.K.Narayan,Mulk Raj Anand, the journey of the Indian English Novel began. -

A Study on the Scientific Approach Towards Vedic Shaivism in Amish Tripathi's the Shiva Trilogy

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 A Study on the Scientific Approach towards Vedic Shaivism in Amish Tripathi’s The Shiva Trilogy Sukanya Chakravarty M.Phil Research Scholar Department of English Rajiv Gandhi University Arunachal Pradesh Abstract: Myth in Indian culture has always been an aura of curiosity. Indian mythology dates back to the times of Lord Rama, Lord Shiva and our firm beliefs in the divine. It also shares with us the stories of Ramayana and Mahabharata. The reality of Ramayana and Mahabharata as true historical events or just an epic story is still arguable. The archaeological excavations give its presence in the structures of the Indus Valley Civilization and the Harappa Cities. Amish Tripathi, the budding Indian writer focuses on such issues of historical relevance in myths. In his works we find the science behind the Vedic customs. The paper attempts to sketch the scientific superiority of the Meluhans people in the novel The Shiva Trilogy. It depicts their firm beliefs and application of medicines and science for practicing a better and healthy life. Somras an eternal drink of bliss is an effort made by the Meluhan scientists to uplift the mankind, whereas the irony is that in the process of making the somras they are indirectly destroying the Mother Nature which in a way means demolishing the mankind. Keywords: Vedic, Myth, Somras, Lord Shiva, Meluha The word ‘myth’ is derived from the Greek word ‘mythos’, which suggests story or word. Myths are moral tales usually set in distant past which are believed as true and which comprises of unearthly, supernatural or legendary characters. -

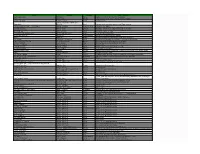

List of Books in Collection

Book Author Category Biju's remarks Mera Naam Joker Abbas K.A Novel made into a film by and starring Raj Kapoor Zed Abbas, Zaheer Cricket autobiography of the former Pakistan cricket captain Things Fall Apart Achebe, Chinua Novel Nigerian writer Aciman, Alexander and Rensin, Twitterature Emmett Novel Famous works of fiction condensed to Twitter format The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy Adams, Douglas Science Fiction a trilogy in four parts The Dilbert Future Adams, Scott Humour workplace humor by the former Pacific Bell executive The Dilbert Principle Adams, Scott Humour workplace humor by the former Pacific Bell executive The White Tiger Adiga, Aravind Novel won Booker Prize in 2008 Teachings of Sri Ramakrishna Advaita Ashram (pub) Essay great saint and philosopher My Country, My Life Advani L.K. Autobiography former Deputy Prime Minister of India Byline Akbar M.J Essay famous journalist turned politician's collection of articles The Woods Alanahally, Shrikrishna Novel translation of Kannada novel Kaadu. Filmed by Girish Karnad Plain Tales From The Raj Allen, Charles (ed) Stories tales from the days of the British rule in India Without Feathers Allen, Woody Play assorted pieces by the Manhattan filmmaker The House of Spirits Allende, Isabelle Novel Chilean writer Celestial Bodies Alharthi, Jokha Novel Omani novel translated by Marilyn Booth An Autobiography Amritraj, Vijay Sports great Indian tennis player Brahmans and Cricket Anand S. Cricket Brahmin community's connection to cricket in the context of the movie Lagan Gauri Anand, -

Satyajit Ray's the Adventures of Feluda

SATYAJIT RAY’S THE ADVENTURES OF FELUDA SATYAJIT RAY: AN INTRODUCTION SATYAJIT RAY, (BORN MAY 2, 1921, CALCUTTA, INDIA—DIED APRIL 23, 1992, CALCUTTA), BENGALI MOTION-PICTURE DIRECTOR, WRITER, AND ILLUSTRATOR WHO BROUGHT THE INDIAN CINEMA TO WORLD RECOGNITION WITH PATHER PANCHALI (1955; THE SONG OF THE ROAD) AND ITS TWO SEQUELS, KNOWN AS THE APU TRILOGY. AS A DIRECTOR RAY WAS NOTED FOR HIS HUMANISM, HIS VERSATILITY, AND HIS DETAILED CONTROL OVER HIS FILMS AND THEIR MUSIC. HE WAS ONE OF THE GREATEST FILMMAKERS OF THE 20TH CENTURY. In 1940 his mother persuaded him to attend art school at Santiniketan, Rabindranath Tagore’s rural university northwest of Calcutta. There Ray, whose interests had been exclusively urban and Western-oriented, was exposed to Indian and other Eastern art and gained a deeper appreciation of both Eastern and Western culture, a harmonious combination that is evident in his films. Returning to Calcutta, Ray in 1943 got a job in a British-owned advertising agency, became its art director within a few years, and also worked for a publishing house as a commercial illustrator, becoming a leading Indian typographer and book-jacket designer. Among the books he illustrated (1944) was the novel Pather Panchali by Bibhuti Bhushan Banarjee, the cinematic possibilities of which began to intrigue him. (W. Andrew Robinson) The film took two-and-a-half years to complete, with the crew, most of whom lacked any experience whatsoever in motion pictures, working on an unpaid basis. Pather Panchali was completed in 1955 and turned out to be both a commercial and a tremendous critical success, first in Bengal and then in the West following a major award at the 1956 Cannes International Film Festival. -

The Indian English Novel of the New Millennium Also by Prabhat K

The Indian English Novel of the New Millennium Also by Prabhat K. Singh Literary Criticism Z Realism in the Romances of Shakespeare Z Dynamics of Poetry in Fiction Z The Creative Contours of Ruskin Bond (ed.) Z A Passage to Shiv K. Kumar Z The Indian English Novel Today (ed.) Poetry Z So Many Crosses Z The Vermilion Moon Z In the Olive Green Z Lamhe (Hindi) Translation into Hindi Z Raat Ke Ajnabi: Do Laghu Upanyasa (Two novellas of Ruskin Bond – A Handful of Nuts and The Sensualist) Z Mahabharat: Ek Naveen Rupantar (Shiv K. Kumar’s The Mahabharata) The Indian English Novel of the New Millennium Edited by Prabhat K. Singh The Indian English Novel of the New Millennium, Edited by Prabhat K. Singh This book first published 2013 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2013 by Prabhat K. Singh All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-4951-0, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-4951-7 For the lovers of the Indian English novel CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................................ ix Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 The Narrative Strands in the Indian English Novel: Needs, Desires and Directions Prabhat K. Singh Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 28 Performance and Promise in the Indian Novel in English Gour Kishore Das Chapter Three ........................................................................................... -

A Critical Assessment of Amish Tripathi's Shiva Trilogy As a Seminal Piece of Popular Fiction

DAYDREAMING AND POPULAR FICTION: A CRITICAL ASSESSMENT OF AMISH TRIPATHI’S SHIVA TRILOGY AS A SEMINAL PIECE OF POPULAR FICTION NEHA KUMARI DR. RAJESH KUMAR Research Scholar, Research Adviser Department of English University Professor V.B.U., Hazaribag, Department of English Jharkhand, INDIA. V.B.U., Hazaribag, Jharkhand, INDIA “Phntasy…can become a source of pleasure for the hearers and spectators at the performance of writer’s work.1” expounds Sigmund Freud, in an informal talk given in 1907 which was subsequently published in 1908 under the title Creative Writers and Day- Dreaming. In his discourse, he presented his idea on the relationship between unconscious fantasy and creative art. Notably, he presented this relationship centreing the “authors of novels, Romances and short-stories2” and not “the authors of epics and tragedies3” whom he refers to as “most highly esteemed by the critic4”. Thus, he talks about popular literature, literary works that have yet to pass through the test of time to certify its creative sustainability. Fantasy is the nucleus of Popular Literature which according to Freud “[he] (an adult) is expected not to go on playing or Phantasying any longer, but to act in a real world”. It may be the reason why Popular fiction or Genre fiction is usually looked down upon by academics (an adult) through the concept of the semi-educated mass reader vs. the highly educated class reader. Popular fiction must connect and satiate the literary appetite of the so called mass reader of popular fiction as opposed to class reader of literary fiction or artistic fiction.