June 17 Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Needle Roller and Cage Assemblies B-003〜022

*保持器付針状/B001-005_*保持器付針状/B001-005 11/05/24 20:31 ページ 1 Needle roller and cage assemblies B-003〜022 Needle roller and cage assemblies for connecting rod bearings B-023〜030 Drawn cup needle roller bearings B-031〜054 Machined-ring needle roller bearings B-055〜102 Needle Roller Bearings Machined-ring needle roller bearings, B-103〜120 BEARING TABLES separable Self-aligning needle roller bearings B-121〜126 Inner rings B-127〜144 Clearance-adjustable needle roller bearings B-145〜150 Complex bearings B-151〜172 Cam followers B-173〜217 Roller followers B-218〜240 Thrust roller bearings B-241〜260 Components Needle rollers / Snap rings / Seals B-261〜274 Linear bearings B-275〜294 One-way clutches B-295〜299 Bottom roller bearings for textile machinery Tension pulleys for textile machinery B-300〜308 *保持器付針状/B001-005_*保持器付針状/B001-005 11/05/24 20:31 ページ 2 B-2 *保持器付針状/B001-005_*保持器付針状/B001-005 11/05/24 20:31 ページ 3 Needle Roller and Cage Assemblies *保持器付針状/B001-005_*保持器付針状/B001-005 11/05/24 20:31 ページ 4 Needle roller and cage assemblies NTN Needle Roller and Cage Assemblies This needle roller and cage assembly is one of the or a housing as the direct raceway surface, without using basic components for the needle roller bearing of a inner ring and outer ring. construction wherein the needle rollers are fitted with a The needle rollers are guided by the cage more cage so as not to separate from each other. The use of precisely than the full complement roller type, hence this roller and cage assembly enables to design a enabling high speed running of bearing. -

Emission Station List by County for the Web

Emission Station List By County for the Web Run Date: June 20, 2018 Run Time: 7:24:12 AM Type of test performed OIS County Station Status Station Name Station Address Phone Number Number OBD Tailpipe Visual Dynamometer ADAMS Active 194 Imports Inc B067 680 HANOVER PIKE , LITTLESTOWN PA 17340 717-359-7752 X ADAMS Active Bankerts Auto Service L311 3001 HANOVER PIKE , HANOVER PA 17331 717-632-8464 X ADAMS Active Bankert'S Garage DB27 168 FERN DRIVE , NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-624-0420 X ADAMS Active Bell'S Auto Repair Llc DN71 2825 CARLISLE PIKE , NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-624-4752 X ADAMS Active Biglerville Tire & Auto 5260 301 E YORK ST , BIGLERVILLE PA 17307 -- ADAMS Active Chohany Auto Repr. Sales & Svc EJ73 2782 CARLISLE PIKE , NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-479-5589 X 1489 CRANBERRY RD. , YORK SPRINGS PA ADAMS Active Clines Auto Worx Llc EQ02 717-321-4929 X 17372 611 MAIN STREET REAR , MCSHERRYSTOWN ADAMS Active Dodd'S Garage K149 717-637-1072 X PA 17344 ADAMS Active Gene Latta Ford Inc A809 1565 CARLISLE PIKE , HANOVER PA 17331 717-633-1999 X ADAMS Active Greg'S Auto And Truck Repair X994 1935 E BERLIN ROAD , NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-624-2926 X ADAMS Active Hanover Nissan EG08 75 W EISENHOWER DR , HANOVER PA 17331 717-637-1121 X ADAMS Active Hanover Toyota X536 RT 94-1830 CARLISLE PK , HANOVER PA 17331 717-633-1818 X ADAMS Active Lawrence Motors Inc N318 1726 CARLISLE PIKE , HANOVER PA 17331 717-637-6664 X 630 HOOVER SCHOOL RD , EAST BERLIN PA ADAMS Active Leas Garage 6722 717-259-0311 X 17316-9571 586 W KING STREET , ABBOTTSTOWN PA ADAMS Active -

W534 Bird Coffin. by Amber Furmage

1 Life Cycle of an Object W534 – Bird Coffin Introduction W534, a bird coffin, currently resides in the animal case of the House of Death, The Egypt Centre, Swansea. The coffin came to Swansea in 1971, having been donated by the Wellcome Trustees. The Egypt Centre have dated it from between the Late Dynastic to the Graeco-Roman Period.1 It was constructed from a yellowish wood of poor quality with a coarse grain. Description Dimensions The bird coffin measures 436mm length by 139mm width at its largest point. The ventral cavity2 measures 330mm length by 68mm width, reaching a depth of 67mm from where the panel would be fitted. The head is 104mm height, making up 23.85% of the entire body. The beak then measures 22mm, 21.15% of the size of the head. The holes in the legs are of uneven proportions, both being 17mm in length but the right hole being 16mm width compared to the 12mm width of the left hole.3 Table 1 – Dimensions of W534 – Measurements taken by Author Feature Length Width Width Height Depth (largest) (smallest) Body 436mm 139mm Tail 104mm Head 80mm 104mm Beak 27mm 22mm Left leg hole 17mm 12mm Right leg hole 17mm 16mm Ventral cavity 330mm 68mm 39mm 67mm 1 The Egypt Centre, 2005. 2 See Figure 1. 3 See Figure 2 and Figure 3. Amber Furmage 2 Brief Description The piece is a yellowish wood4 carved to into a zoomorphic shape and coated in paint. The paint varies between features, some being black and other sections being red.5 The lack of paint on the top of the head6 may simply be an abrasion, however, due to the circular nature of the deficient, is perhaps more likely to be an area that had been covered up prior to painting and is now missing this element. -

119 Original Article the GOLDEN SHRINES of TUTANKHAMUN

id9070281 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com Egyptian Journal of Archaeological and Restoration Studies "EJARS" An International peer-reviewed journal published bi-annually Volume 2, Issue 2, December - 2012: pp: 119-130 www. ejars.sohag-univ.edu.eg Original article THE GOLDEN SHRINES OF TUTANKHAMUN AND THEIR INTENDED BURIAL PLACE Soliman, R. Lecturer, Tourism guidance dept., Faculty of Archaeology & Tourism guidance, Misr Univ. for Sciences & Technology, 6th October city, Egypt E-mail: [email protected] Received 3/5/2012 Accepted 12/10/2012 Abstract The most famous tomb at the Valley of the Kings, KV 62 housed so far the most intact discovery of royal funerary treasures belonging to the eighteenth dynasty boy-king Tutankhamun. The tomb has a simple architectural plan clearly prepared for a non- royal burial. However, the hastily death of Tutankhamun at a young age caused his interment in such unusually small tomb. The treasures discovered were immense in number, art finesse and especially in the amount of gold used. Of these treasures the largest shrine of four shrines laid in the burial chamber needed to be dismantled and reassembled in the tomb because of its immense size. Clearly the black marks on this shrine helped in the assembly and especially the orientation in relation to the burial chamber. These marks are totally incorrect and prove that Tutankhamun was definitely intended to be buried in another tomb. Keywords: KV62, WV23, Golden shrines, Tutankhamun, Burial chamber, Orientation. 1. Introduction Tutankhamun was only nine and the real cause of his death remains years old when he got to throne; at that enigmatic. -

Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family

Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family Zahi Hawass; Yehia Z. Gad; Somaia Ismail; et al. JAMA. 2010;303(7):638-647 (doi:10.1001/jama.2010.121) Online article and related content current as of October 14, 2010. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/303/7/638 Supplementary material eSupplement http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/303/7/638/DC1 Correction Contact me if this article is corrected. Citations This article has been cited 7 times. Contact me when this article is cited. Topic collections Neurology; Neurogenetics; Movement Disorders; Rheumatology; Musculoskeletal Syndromes (Chronic Fatigue, Gulf War); Malaria; Genetics; Genetic Disorders; Humanities; History of Medicine; Infectious Diseases Contact me when new articles are published in these topic areas. Related Articles published in King Tutankhamun, Modern Medical Science, and the Expanding Boundaries of the same issue Historical Inquiry Howard Markel. JAMA. 2010;303(7):667. Related Letters King Tutankhamun’s Family and Demise Eline D. Lorenzen et al. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2471. Brenda J. Baker. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2471. James G. Gamble. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2472. Irwin M. Braverman et al. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2472. Christian Timmann et al. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2473. Subscribe Email Alerts http://jama.com/subscribe http://jamaarchives.com/alerts Permissions Reprints/E-prints [email protected] [email protected] http://pubs.ama-assn.org/misc/permissions.dtl Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on October 14, 2010 ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun’s Family Zahi Hawass, PhD Context The New Kingdom in ancient Egypt, comprising the 18th, 19th, and 20th Yehia Z. -

Letting Celebrity Cruises® Arrange Your Private Car/Van Experience in Europe

Letting Celebrity Cruises® arrange your private car/van experience in Europe. When you book a Celebrity Cruises private car/van arrangement, your tour will be run by one of a select group of guides and operators handpicked by us to meet our high standards. By booking private arrangements through Celebrity Cruises, you’ll enjoy the peace of mind that comes with knowing we’ve handled the details so you can relax and enjoy your day. Private car/van arrangements allow you to choose an itinerary geared toward your own personal interests, convenience and flexibility. For guests who want to explore individually or in a small group, you have the opportunity to tour the city and/or surrounding areas via a private vehicle. Two ways to purchase private arrangements: 1. Private car/van arrangements are available for online booking in over 50 Europe ports (refer to the list of currently offered private arrangements starting on page 3). Please visit celebritycruises.com for complete detailed information including pricing, terms and conditions. 2. Should you determine you would like a more customized tour program with entrance fees included or a specific itinerary in mind, please find the Custom Private Arrangement Request Form on the next page and complete the required information. Email the form to [email protected] or fax to (305) 579-0193. A few things to keep in mind: • Vehicles are offered on a half -day or full-day basis. • A car will accommodate 1 to 3 guests, with a maximum capacity requiring 3 passengers sitting in the back seat. • A van will accommodate 4 to 8 passengers. -

Ancient Ancient Egyptian Attitude to Death

NOVEMBER / DECEMBER 2001 £2.95 AANCIENTNCIENT EGYPTEGYPT THE HISTORY, PEOPLE AND CULTURE OF THE NILE VALLEY The Amarna Heresy: First part of conference report... Sex, serpents and subterfuge: Cleopatra in the movies Our Nine Measures of Magic series concludes Heka at the Louvre NEWS, REVIEWS AND INTERVIEWS PLUS AND OUR SPECIAL TRAVEL SECTION Ancient Egypt Vol 2 Issue 3 AN UNFORGETTABLE TRIP WINTO EGYPT WITH AWT Subscribe When you subscribe to Ancient Egypt you not only get each issue delivered to your doorstep but you also get it before your newsagent! Subscribing is easy, simply fi ll in the order form below or call our order hotline on 0161 872 3319 or subscribe online at www.ancientegyptmagazine.com/subs.htm Please specify any back issues you require in the boxes below. VOLUME 1 VOLUME 2 VOLUME 3 VOLUME 4 VOLUME 5 VOLUME 6 1MAY/JUNE 2000 1JUNE/JULY 2001 1JULY/AUG 2002 1JULY/AUG 2003 1AUG/SEPT 2004 1AUG/SEPT 2005 2JULY/AUG 2000 2AUG/SEPT 2001 2SEPT/OCT 2002 2OCT/NOV 2003 2OCT/NOV 2004 2OCT/NOV 2005 3SEPT/OCT 2000 4JAN/FEB 2002 3NOV/DEC 2002 3DEC/JAN 2004 3DEC/JAN 2004/5 3DEC/JAN 2005/6 4NOV/DEC 2000 5MAR/APR 2002 4JAN/FEB 2003 4FEB/MAR 2004 4FEB/MAR 2005 4FEB/MAR 2006 5JAN/FEB 2001 6MAY/JUNE 2002 5MAR/APRI2003 5APR/MAY 2004 5APR/MAY 2005 6APR/MAY 2001 6MAY/ JUN 2003 6JUNE/JULY 2004 6JUNE/JULY 2005 £4.00 per copy (UK), £4.50 per copy (Europe), £6.00 per copy (Rest of the World) Yes! I would like to subscribe to Ancient Egypt Starting Issue (SUBS ONLY) : ........................................................................ -

DSFRA IKEN Report Template

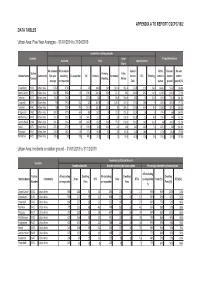

APPENDIX A TO REPORT CSCPC/19/2 DATA TABLES Urban Area: Five-Year Averages – 01/04/2014 to 31/04/2019 Incidents on station grounds Location False Pump Attendances Overview Fires Special Service Alarm All incidents All incidents Special All by On own On own Station Primary: False Station Name Community five-year excluding Co-responder All Primary Secondary Service RTC Flooding station's station station Number Dwelling Alarms average co-responder Calls pumps ground ground (%) Greenbank KV50 Urban Area 878.6 878.6 0 245 104.6 56.6 140.4 361.4 271.8 21.6 24.6 1424.8 974.2 68.4% Danes Castle KV32 Urban Area 832.6 830.8 1.8 198.8 126.4 56.6 72.4 385 248.4 29.2 14.8 1090.6 849.4 77.9% Torquay KV17 Urban Area 744.8 744.8 0 207.8 111 59 96.8 306.8 230 36 15.8 919.8 776.4 84.4% Crownhill KV49 Urban Area 742 741.8 0.2 227 100.6 43 126.4 337.4 177.4 28.6 9 878.4 680.6 77.5% Taunton KV61 Urban Area 734 733.4 0.6 227.8 132.8 56.6 95 284.6 221.6 65.4 8.4 1038.8 901.8 86.8% Bridgwater KV62 Urban Area 584.2 577.6 6.6 160 88.2 38 71.8 231.8 192.4 56 8 774.4 666 86.0% Middlemoor KV59 Urban Area 537.6 535.8 1.8 144.2 91.2 33 53 239.6 153.8 51 8.8 724.4 444 61.3% Camels Head KV48 Urban Area 491.6 491.2 0.4 162.8 85.2 50.4 77.6 178.6 150.2 16.6 11.8 638 390.2 61.2% Yeovil KV73 Urban Area 471.6 471.6 0 139.6 78.6 34.8 61 191 141 46.8 7.4 674.2 569 84.4% Plympton KV47 Urban Area 218.4 204.4 14 57.8 34.8 12 23 87.8 72.4 18.6 3 170.6 135.8 79.6% Plymstock KV51 Urban Area 185.8 185 0.8 48.4 27.4 12 21 76.8 60.6 12.6 2.6 165.4 123.8 74.8% Urban Area: Incidents on -

Expanding the Toolkit for Metabolic Engineering

Expanding the Toolkit for Metabolic Engineering Yao Zong (Andy) Ng Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Yao Zong (Andy) Ng All rights reserved ABSTRACT Expanding the Toolkit for Metabolic Engineering Yao Zong (Andy) Ng The essence of metabolic engineering is the modification of microbes for the overproduction of useful compounds. These cellular factories are increasingly recognized as an environmentally-friendly and cost-effective way to convert inexpensive and renewable feedstocks into products, compared to traditional chemical synthesis from petrochemicals. The products span the spectrum of specialty, fine or bulk chemicals, with uses such as pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, flavors and fragrances, agrochemicals, biofuels and building blocks for other compounds. However, the process of metabolic engineering can be long and expensive, primarily due to technological hurdles, our incomplete understanding of biology, as well as redundancies and limitations built into the natural program of living cells. Combinatorial or directed evolution approaches can enable us to make progress even without a full understanding of the cell, and can also lead to the discovery of new knowledge. This thesis is focused on addressing the technological bottlenecks in the directed evolution cycle, specifically de novo DNA assembly to generate strain libraries and small molecule product screens and selections. In Chapter 1, we begin by examining the origins of the field of metabolic engineering. We review the classic “design–build–test–analyze” (DBTA) metabolic engineering cycle and the different strategies that have been employed to engineer cell metabolism, namely constructive and inverse metabolic engineering. -

The Gazelle in Ancient Egyptian Art Image and Meaning

Uppsala Studies in Egyptology - 6 - Department of Archaeology and Ancient History Uppsala University For my parents Dorrit and Hindrik Åsa Strandberg The Gazelle in Ancient Egyptian Art Image and Meaning Uppsala 2009 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in the Auditorium Minus of the Museum Gustavianum, Uppsala, Friday, October 2, 2009 at 09:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Strandberg, Åsa. 2009. The Gazelle in Ancient Egyptian Art. Image and Meaning. Uppsala Studies in Egyptology 6. 262 pages, 83 figures. Published by the Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University. xviii +262 pp. ISSN 1650-9838, ISBN 978-91-506-2091-7. This thesis establishes the basic images of the gazelle in ancient Egyptian art and their meaning. A chronological overview of the categories of material featuring gazelle images is presented as a background to an interpretation. An introduction and review of the characteristics of the gazelle in the wild are presented in Chapters 1-2. The images of gazelle in the Predynastic material are reviewed in Chapter 3, identifying the desert hunt as the main setting for gazelle imagery. Chapter 4 reviews the images of the gazelle in the desert hunt scenes from tombs and temples. The majority of the motifs characteristic for the gazelle are found in this context. Chapter 5 gives a typological analysis of the images of the gazelle from offering processions scenes. In this material the image of the nursing gazelle is given particular importance. Similar images are also found on objects, where symbolic connotations can be discerned (Chapter 6). -

Come My Staff, I Lean Upon You: an Iconographic and Contextual Study of Sticks and Staves from 18Th Dynasty Egypt

The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Sciences Come My Staff, I Lean Upon You: an Iconographic and Contextual Study of Sticks and Staves from 18th Dynasty Egypt A Thesis Submitted to The Department of Sociology, Anthropology, Psychology and Egyptology (SAPE) In partial fulfillment of the requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts By: Nicholas R. Brown Under the Supervision of Dr. Salima Ikram First Reader: Dr. Lisa Sabbahy Second Reader: Dr. Fayza Haikal December, 2015 DEDICATION “All men dream, but not equally. Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds, wake in the day to find that it was vanity: but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act on their dreams with open eyes, to make them possible. This I did.” -T. E. Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom To my grandmother, Nana Joan. For first showing me the “Wonderful Things” of ancient Egypt. I love you dearly. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are many individuals and institutions to whom I would like to express my deepest gratitude and thankfulness. Without their help, encouragement, support, and patience I would not have been able to complete my degree nor this thesis. Firstly, to my advisor Dr. Salima Ikram: I am grateful for your suggesting the idea of studying sticks in ancient Egypt, and for the many lessons that you have taught and opportunities you have provided for me throughout this entire process. I am, hopefully, a better scholar (and speller!) because of your investment in my research. Thank you. To my readers Doctors Lisa Sabbahy and Fayza Haikal, thank you for taking the time to review, comment upon, and edit my thesis draft. -

Images of the Rekhyt from Ancient Egypt

AE 38 cover.qxd 6/9/06 1:40 pm Page 1 AEPrelim36.qxd 13/02/1950 19:25 Page 2 AEPrelim38.qxd 13/02/1950 19:25 Page 3 CONTENTS features ANCIENT EGYPT www.ancientegyptmagazine.com October/November 2006 From our Egypt Correspondent VOLUME 7, NO 2: ISSUE NO. 38 9 Ayman Wahby Taher with the latest news from Egypt and details of a new museum at Saqqara. EDITOR: Robert B. Partridge, 6 Branden Drive Knutsford, Cheshire, WA16 8EJ, UK Friends of Nekhen News Tel. 01565 754450 Renée Friedman looks at the presence of Nubians Email [email protected] 19 in the city at Hierakonpolis, and their lives there, as revealed in the finds from their tombs. ASSISTANT EDITOR: Peter Phillips The New Tomb CONSULTANT EDITOR: Professor Rosalie David, OBE in the Valley of the Kings EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS: 26 The fourth update on the recent discovery and the final clearance of the small chamber. Victor Blunden, Peter Robinson, Hilary Wilson EGYPT CORRESPONDENT ANOTHER new tomb in the Valley Ayman Wahby Taher of the Kings? 31 Nicholas Reeves reveals the latest news on the PUBLISHED BY: possibility of another tomb in the Royal Valley. Empire Publications, 1 Newton Street, Manchester, M1 1HW, UK Royal Mummies on view in the Tel: 0161 872 3319 Egyptian Museum Fax: 0161 872 4721 35 A brief report on the opening of the second mummy room in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo. ADVERTISEMENT MANAGER: Michael Massey Tel. 0161 928 2997 The Ancient Stones Speak Pam Scott, in the first of three major articles, gives a SUBSCRIPTIONS: 36 practical guide to enable AE readers to read and understand the ancient texts written on temple and Mike Hubbard tomb walls, statues and stelae.