W534 Bird Coffin. by Amber Furmage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dogs and Cats and Birds, Oh My!

DOGS AND CATS AND BIRDS, OH MY! The Penn Museum’s Egyptian Animal Mummies by christina griffith While most visitors to the museum are drawn to the mummified people from ancient egypt, humans are not alone in the afterlife: dozens of animal mummies are also part of the museum’s egyptian collection. We have amassed a variety of birds (ibis, falcon, and and examine them. Te new West Wing Conservation hawk), a shrew, small crocodiles, cats, bundles of lizards and Teaching Labs in the Museum, built in 2014, are and snakes, and a famous canine companion to a man equipped with an x-ray unit, and a CT scan of one falcon named Hapimen, known around the Museum as Hapi- mummy was performed at the GE Inspection Technolo- puppy. Many of our animal mummies were excavated gies facility in Lewistown, PA. in the late 1800s by Sir Flinders Petrie and the Egypt Exploration Society. Some were purchased from collec- tors in the early 20th century. In 1978, selected mummies were imaged at the Penn Veterinary School for the Secrets and Science exhibition. In 2016, the frst phase of the new Ancient Egypt and Nubia Galleries project involved re-housing our animal OPPOSITE: The x-rays and bound mummy of an ibis from the Museum’s Egyptian collection. Ibis are associated with Thoth, the god of wisdom, mummies, which provided a perfect opportunity for magic, and writing. PM object E12443. ABOVE: A mummified shrew. conservators Molly Gleeson and Alexis North to image PM object E12435. EXPEDITION Winter 2018 23 DOGS AND CATS AND BIRDS, OH MY! of animals were mummifed in Egypt, from cats and dogs to baboons, fsh, deer, bulls, and goats. -

Mummies at Manchester

The University of Manchester Research Mummies at Manchester Document Version Final published version Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Mcknight, L., & Atherton-Woolham, S. (2019). Mummies at Manchester: applying the Manchester Methodology to the study of mummified animal remains from ancient Egypt. In S. Porcier, S. Ikram, & S. Pasquali (Eds.), Creatures of Earth, Water and Sky : Essays on Animals in Ancient Egypt and Nubia (pp. 243-250). Sidestone Press. Published in: Creatures of Earth, Water and Sky Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:10. Oct. 2021 & PASQUALI (EDS) PASQUALI & PORCIER, IKRAM PORCIER, CREATURES OF EARTH, WATER, AND SKY CREATURES OF EARTH, WATER, AND SKY Ancient Egyptians always had an intense and complex relationship with animals in daily life as well as in religion. Despite the fact that re- search on this relationship has been a topic of study, gaps in our knowledge still remain. -

119 Original Article the GOLDEN SHRINES of TUTANKHAMUN

id9070281 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com Egyptian Journal of Archaeological and Restoration Studies "EJARS" An International peer-reviewed journal published bi-annually Volume 2, Issue 2, December - 2012: pp: 119-130 www. ejars.sohag-univ.edu.eg Original article THE GOLDEN SHRINES OF TUTANKHAMUN AND THEIR INTENDED BURIAL PLACE Soliman, R. Lecturer, Tourism guidance dept., Faculty of Archaeology & Tourism guidance, Misr Univ. for Sciences & Technology, 6th October city, Egypt E-mail: [email protected] Received 3/5/2012 Accepted 12/10/2012 Abstract The most famous tomb at the Valley of the Kings, KV 62 housed so far the most intact discovery of royal funerary treasures belonging to the eighteenth dynasty boy-king Tutankhamun. The tomb has a simple architectural plan clearly prepared for a non- royal burial. However, the hastily death of Tutankhamun at a young age caused his interment in such unusually small tomb. The treasures discovered were immense in number, art finesse and especially in the amount of gold used. Of these treasures the largest shrine of four shrines laid in the burial chamber needed to be dismantled and reassembled in the tomb because of its immense size. Clearly the black marks on this shrine helped in the assembly and especially the orientation in relation to the burial chamber. These marks are totally incorrect and prove that Tutankhamun was definitely intended to be buried in another tomb. Keywords: KV62, WV23, Golden shrines, Tutankhamun, Burial chamber, Orientation. 1. Introduction Tutankhamun was only nine and the real cause of his death remains years old when he got to throne; at that enigmatic. -

Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family

Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family Zahi Hawass; Yehia Z. Gad; Somaia Ismail; et al. JAMA. 2010;303(7):638-647 (doi:10.1001/jama.2010.121) Online article and related content current as of October 14, 2010. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/303/7/638 Supplementary material eSupplement http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/303/7/638/DC1 Correction Contact me if this article is corrected. Citations This article has been cited 7 times. Contact me when this article is cited. Topic collections Neurology; Neurogenetics; Movement Disorders; Rheumatology; Musculoskeletal Syndromes (Chronic Fatigue, Gulf War); Malaria; Genetics; Genetic Disorders; Humanities; History of Medicine; Infectious Diseases Contact me when new articles are published in these topic areas. Related Articles published in King Tutankhamun, Modern Medical Science, and the Expanding Boundaries of the same issue Historical Inquiry Howard Markel. JAMA. 2010;303(7):667. Related Letters King Tutankhamun’s Family and Demise Eline D. Lorenzen et al. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2471. Brenda J. Baker. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2471. James G. Gamble. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2472. Irwin M. Braverman et al. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2472. Christian Timmann et al. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2473. Subscribe Email Alerts http://jama.com/subscribe http://jamaarchives.com/alerts Permissions Reprints/E-prints [email protected] [email protected] http://pubs.ama-assn.org/misc/permissions.dtl Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on October 14, 2010 ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun’s Family Zahi Hawass, PhD Context The New Kingdom in ancient Egypt, comprising the 18th, 19th, and 20th Yehia Z. -

Animal Mummies from Tomb 3508, North Saqqara, Egypt Stephanie Atherton-Woolham1, Lidija Mcknight1,*, Campbell Price2 & Judith Adams3,4

Imaging the gods: animal mummies from Tomb 3508, North Saqqara, Egypt Stephanie Atherton-Woolham1, Lidija McKnight1,*, Campbell Price2 & Judith Adams3,4 A collection of mummified animals discovered in 1964 in a Third Dynasty mastaba tomb at North Saqqara, Egypt, offers the unusual and unique opportunity to study a group of mum- mies from a discrete ancient Egyptian context. Macroscopic and radiographic analyses of 16 mummy bundles allow parallels to be drawn between the nature of their internal contents and their external decoration. The evidence suggests that incomplete and skeletonised ani- mal remains fulfilled the equivalent votive function as complete, mummified remains, and that a centralised industry may have pro- duced votive mummies for deposition at the Saqqara Necropolis. Keywords: Egypt, Saqqara, animal mummies, votive offerings, experimental archaeology Introduction Animal mummies are commonly divided into four categories: pets, victual (preserved food), cult animals and votive offerings (Ikram 2015:1–16), with the latter being the most common type found in museum collections around the world. Since 2010, research at the University of Manchester has collated data on these widely distributed objects (McKnight et al. 2011)to understand further their votive purpose. Minimally invasive clinical imaging is used to iden- tify the materials and methods used in their construction to gain additional understanding of their votive purpose. To date, the project has analysed over 960 animal mummies, although 1 The University of Manchester, -

Cyberscribe 188-April 2011 Copy

1 CyberScribe 188 – April 2011 Egypt has become quieter for the moment, now that Mubarak has left, and before the elections. In this wild melee that was the revolution, Zahi Hawass was forced out…and many were gleefully dancing on his grave. The CyberScribe warned people that it would be a mistake to write him out of the script right away. He has been very wily and a strong fighter. Apparently someone forgot the oak stake through his heart, or wherever, because the great man is back. He is once again the Minister of Antiquities. An article in ‘Arts Beat’ (http://snipurl.com/27qyln) was one of many sources that broke the news! Here is an abbreviated account of his return: “Zahi Hawass, who resigned as Egypt’s minister of antiquities less than a month ago under criticism for his close ties to former President Hosni Mubarak, was reappointed to the post on Wednesday, Agence France-Presse reported, citing an Egyptian news report; Mr. Hawass, reached by phone, confirmed his reappointment. “Mr. Hawass, a powerful figure in the world of Egyptology, was promoted to a cabinet position in the early days of the uprising, and drew the animosity of the revolutionaries by saying at the time that Mr. Mubarak should be allowed to hold power for another six months. He also said that Egypt’s museums and archeological sites were largely secure and that cases of looting were very limited. In the weeks that followed, that turned out not to be the case: several dozen objects were stolen from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo during a break-in on Jan. -

DSFRA IKEN Report Template

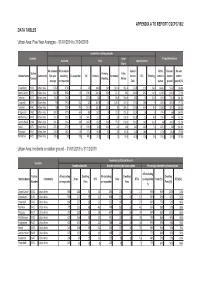

APPENDIX A TO REPORT CSCPC/19/2 DATA TABLES Urban Area: Five-Year Averages – 01/04/2014 to 31/04/2019 Incidents on station grounds Location False Pump Attendances Overview Fires Special Service Alarm All incidents All incidents Special All by On own On own Station Primary: False Station Name Community five-year excluding Co-responder All Primary Secondary Service RTC Flooding station's station station Number Dwelling Alarms average co-responder Calls pumps ground ground (%) Greenbank KV50 Urban Area 878.6 878.6 0 245 104.6 56.6 140.4 361.4 271.8 21.6 24.6 1424.8 974.2 68.4% Danes Castle KV32 Urban Area 832.6 830.8 1.8 198.8 126.4 56.6 72.4 385 248.4 29.2 14.8 1090.6 849.4 77.9% Torquay KV17 Urban Area 744.8 744.8 0 207.8 111 59 96.8 306.8 230 36 15.8 919.8 776.4 84.4% Crownhill KV49 Urban Area 742 741.8 0.2 227 100.6 43 126.4 337.4 177.4 28.6 9 878.4 680.6 77.5% Taunton KV61 Urban Area 734 733.4 0.6 227.8 132.8 56.6 95 284.6 221.6 65.4 8.4 1038.8 901.8 86.8% Bridgwater KV62 Urban Area 584.2 577.6 6.6 160 88.2 38 71.8 231.8 192.4 56 8 774.4 666 86.0% Middlemoor KV59 Urban Area 537.6 535.8 1.8 144.2 91.2 33 53 239.6 153.8 51 8.8 724.4 444 61.3% Camels Head KV48 Urban Area 491.6 491.2 0.4 162.8 85.2 50.4 77.6 178.6 150.2 16.6 11.8 638 390.2 61.2% Yeovil KV73 Urban Area 471.6 471.6 0 139.6 78.6 34.8 61 191 141 46.8 7.4 674.2 569 84.4% Plympton KV47 Urban Area 218.4 204.4 14 57.8 34.8 12 23 87.8 72.4 18.6 3 170.6 135.8 79.6% Plymstock KV51 Urban Area 185.8 185 0.8 48.4 27.4 12 21 76.8 60.6 12.6 2.6 165.4 123.8 74.8% Urban Area: Incidents on -

The Gazelle in Ancient Egyptian Art Image and Meaning

Uppsala Studies in Egyptology - 6 - Department of Archaeology and Ancient History Uppsala University For my parents Dorrit and Hindrik Åsa Strandberg The Gazelle in Ancient Egyptian Art Image and Meaning Uppsala 2009 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in the Auditorium Minus of the Museum Gustavianum, Uppsala, Friday, October 2, 2009 at 09:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Strandberg, Åsa. 2009. The Gazelle in Ancient Egyptian Art. Image and Meaning. Uppsala Studies in Egyptology 6. 262 pages, 83 figures. Published by the Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University. xviii +262 pp. ISSN 1650-9838, ISBN 978-91-506-2091-7. This thesis establishes the basic images of the gazelle in ancient Egyptian art and their meaning. A chronological overview of the categories of material featuring gazelle images is presented as a background to an interpretation. An introduction and review of the characteristics of the gazelle in the wild are presented in Chapters 1-2. The images of gazelle in the Predynastic material are reviewed in Chapter 3, identifying the desert hunt as the main setting for gazelle imagery. Chapter 4 reviews the images of the gazelle in the desert hunt scenes from tombs and temples. The majority of the motifs characteristic for the gazelle are found in this context. Chapter 5 gives a typological analysis of the images of the gazelle from offering processions scenes. In this material the image of the nursing gazelle is given particular importance. Similar images are also found on objects, where symbolic connotations can be discerned (Chapter 6). -

June 17 Newsletter

ESSEX EGYPTOLOGY GROUP Newsletter 108 June/July 2017 DATES FOR YOUR DIARY 4th June Hatshepsut’s temple at Deir el-Bahri: Sergio Alarcon Robledo 2nd July The stone village at Amarna: Anna Garnett 6th August Short talks, book auction and annual general meeting 3rd September Justice in ancient Egypt: Alexandre Loktionov 1st October Ancient Egyptian Furniture: from the earliest to those “wonderful things” of the New Kingdom: Dr Geoffrey Killen This month we welcome, from Madrid, Sergio Alarcón Robledo. Sergio is one of the architects working at the Polish-Egyptian Archaeological and Conservation Mission of the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari. He has studied Architecture at the Technical University of Madrid, and the MPhil of Egyptology at the University of Cambridge. His work has mainly focused on the excavation and interpretation of architectural evidence from ancient Egypt. His fieldwork experience includes his work at Deir el-Bahari and some nearby New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period tombs. This coming season he will also join the Middle Kingdom Theban Project and the Egypt Exploration Society’s Mission at Zawyet Sultan. The temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari, is one of the oldest known New Kingdom royal buildings, and is key for the interpretation of the Theban mortuary temples, as well as for a better understanding of how the royal identity was shaped in the beginning of the New Kingdom. His talk will give an overview of the temple showing both its importance in the development of New Kingdom traditions and explaining the main archaeological and restoration works which have been carried out since 1855. -

Come My Staff, I Lean Upon You: an Iconographic and Contextual Study of Sticks and Staves from 18Th Dynasty Egypt

The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Sciences Come My Staff, I Lean Upon You: an Iconographic and Contextual Study of Sticks and Staves from 18th Dynasty Egypt A Thesis Submitted to The Department of Sociology, Anthropology, Psychology and Egyptology (SAPE) In partial fulfillment of the requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts By: Nicholas R. Brown Under the Supervision of Dr. Salima Ikram First Reader: Dr. Lisa Sabbahy Second Reader: Dr. Fayza Haikal December, 2015 DEDICATION “All men dream, but not equally. Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds, wake in the day to find that it was vanity: but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act on their dreams with open eyes, to make them possible. This I did.” -T. E. Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom To my grandmother, Nana Joan. For first showing me the “Wonderful Things” of ancient Egypt. I love you dearly. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are many individuals and institutions to whom I would like to express my deepest gratitude and thankfulness. Without their help, encouragement, support, and patience I would not have been able to complete my degree nor this thesis. Firstly, to my advisor Dr. Salima Ikram: I am grateful for your suggesting the idea of studying sticks in ancient Egypt, and for the many lessons that you have taught and opportunities you have provided for me throughout this entire process. I am, hopefully, a better scholar (and speller!) because of your investment in my research. Thank you. To my readers Doctors Lisa Sabbahy and Fayza Haikal, thank you for taking the time to review, comment upon, and edit my thesis draft. -

ANIMAL MUMMIES from ANCIENT EGYPT by Salima Ikram

™ MUSEUMANTHRO OF NATURAL HISTORY PUBLICATIONNOTES FOR EDUCATORS VOLUME 33 NO. 1 SPRING 2012 CREATURES OF THE GODS: ANIMAL MUMMIES FROM ANCIENT EGYPT by Salima Ikram ˜ ˜ ˜ f you’re a pet lover, you might want to take a time mans, enjoyed splendid burials, complete with elaborate machine back to Ancient Egypt where you could coffins and food offerings. Iarrange to keep your pet with you – forever! Al- Pets were only one of several kinds of animal though mummies are synonymous with ancient Egypt, mummies, which actually far outnumber human mum- few people realize that the ancient Egyptians also mum- mies. Mummification was carried out in order to pre- mified animals, including their pets. serve the body for eternity so that the soul (ka and ba) Pet mummies are the kind of mummy that reso- could inhabit it in the Afterlife. A large range of animal nates most closely with us now. From the Old Kingdom species were mummified, including cattle, baboons, rams, (c. 2663-2195 BC) onward, Egyptians are pictured in lions, cats, dogs, hyenas, fish, bats, owls, gazelles, goats, their tombs with their beloved pets, thus ensuring their crocodiles, shrews, scarab beetles, ibises, falcons, snakes, continued joint existence in the Afterlife. Occasionally lizards, and many different types of birds. Even croco- the pets would even have their names carved above their dile eggs and dung balls were wrapped up and pre- image, providing further insurance for their eternal life. sented as offerings. This was particularly true of hunting dogs that were im- Animals were mummified throughout Egyp- mortalized with their names such as “Swifter than the tian history; however, the majority of animal mummies Gazelle” or “Slayer of Oryx”. -

ABSTRACT Carl Nicholas Reeves STUDIES in the ARCHAEOLOGY

ABSTRACT Carl Nicholas Reeves STUDIES IN THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE VALLEY OF THE KINGS, with particular reference to tomb robbery and the caching of the royal mummies This study considers the physical evidence for tomb robbery on the Theban west bank, and its resultant effects, during the New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period. Each tomb and deposit known from the Valley of the Kings is examined in detail, with the aims of establishing the archaeological context of each find and, wherever possible, isolating and comparing the evidence for post-interment activity. The archaeological and documentary evidence pertaining to the royal caches from Deir el-Bahri, the tomb of Amenophis II and elsewhere is drawn together, and from an analysis of this material it is possible to suggest the routes by which the mummies arrived at their final destinations. Large-scale tomb robbery is shown to have been a relatively uncommon phenomenon, confined to periods of political and economic instability. The caching of the royal mummies may be seen as a direct consequence of the tomb robberies of the late New Kingdom and the subsequent abandonment of the necropolis by Ramesses XI. Associated with the evacuation of the Valley tombs may be discerned an official dismantling of the burials and a re-absorption into the economy of the precious commodities there interred. STUDIES IN THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE VALLEY OF THE KINGS, with particular reference to tomb robbery and the caching of the royal mummies (Volumes I—II) Volume I: Text by Carl Nicholas Reeves Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Oriental Studies University of Durham 1984 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author.