Dicara Is Wrong About Boston Buses Don't Ban Them, Let's Find Ways to Help Them Work Better

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MIT Kendall Square

Ridership and Service Statistics Thirteenth Edition 2010 Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority MBTA Service and Infrastructure Profile July 2010 MBTA Service District Cities and Towns 175 Size in Square Miles 3,244 Population (2000 Census) 4,663,565 Typical Weekday Ridership (FY 2010) By Line Unlinked Red Line 241,603 Orange Line 184,961 Blue Line 57,273 Total Heavy Rail 483,837 Total Green Line (Light Rail & Trolley) 236,096 Bus (includes Silver Line) 361,676 Silver Line SL1 & SL2* 14,940 Silver Line SL4 & SL5** 15,086 Trackless Trolley 12,364 Total Bus and Trackless Trolley 374,040 TOTAL MBTA-Provided Urban Service 1,093,973 System Unlinked MBTA - Provided Urban Service 1,093,973 Commuter Rail Boardings (Inbound + Outbound) 132,720 Contracted Bus 2,603 Water Transportation 4,372 THE RIDE Paratransit Trips Delivered 6,773 TOTAL ALL MODES UNLINKED 1,240,441 Notes: Unlinked trips are the number of passengers who board public transportation vehicles. Passengers are counted each time they board vehicles no matter how many vehicles they use to travel from their origin to their destination. * Average weekday ridership taken from 2009 CTPS surveys for Silver Line SL1 & SL2. ** SL4 service began in October 2009. Ridership represents a partial year of operation. File: CH 01 p02-7 - MBTA Service and Infrastructure Profile Jul10 1 Annual Ridership (FY 2010) Unlinked Trips by Mode Heavy Rail - Red Line 74,445,042 Total Heavy Rail - Orange Line 54,596,634 Heavy Rail Heavy Rail - Blue Line 17,876,009 146,917,685 Light Rail (includes Mattapan-Ashmont Trolley) 75,916,005 Bus (includes Silver Line) 108,088,300 Total Rubber Tire Trackless Trolley 3,438,160 111,526,460 TOTAL Subway & Bus/Trackless Trolley 334,360,150 Commuter Rail 36,930,089 THE RIDE Paratransit 2,095,932 Ferry (ex. -

Building a Better T in the Era of Covid-19

Building a Better T in the Era of Covid-19 MBTA Advisory Board September 17, 2020 General Manager Steve Poftak 1 Agenda 1. Capital Project Updates 2. Ridership Update 3. Ride Safer 4. Crowding 5. Current Service and Service Planning 2 Capital Project Updates 3 Surges Complete | May – August 2020 Leveraged low ridership while restrictions are in place due to COVID-19 directives May June July August D Branch (Riverside to Kenmore) Two 9-Day Closures C Branch (Cleveland Circle to Kenmore) E Branch (Heath to Symphony) Track & Signal Improvements, Fenway Portal Flood 28-Day Full Closure 28-Day Full Closure Protection, Brookline Hills TOD Track & Intersection Upgrades Track & Intersection Upgrades D 6/6 – 6/14 D 6/20 – 6/28 C 7/5 – 8/1 E 8/2 – 8/29 Blue Line (Airport to Bowdoin) Red Line (Braintree to Quincy) 14-Day Closure Harbor Tunnel Infrastructure Upgrades On-call Track 2, South Shore Garages, Track Modernization BL 5/18 – 5/31 RL 6/18 -7/1 4 Shuttle buses replaced service Ridership Update 5 Weekday Ridership by Line and Mode - Indexed to Week of 2/24 3/17: Restaurants and 110 bars closed, gatherings Baseline: limited to 25 people Average weekday from 2/24-2/28 100 MBTA service reduced Sources: 90 3/24: Non-essential Faregate counts for businesses closed subway lines, APC for 80 buses, manual counts at terminals for Commuter Rail, RIDE 70 vendor reports 6/22: Phase 2.2 – MBTA 6/8: Phase 2.1 60 increases service Notes: Recent data preliminary 50 5/18-6/1: Blue Line closed for 40 accelerated construction Estimated % of baseline ridership -

Tobin Bridge/Chelsea Curves Rehabilitation Project

Tobin Bridge/Chelsea Curves Rehabilitation Project PROJECT OVERVIEW The Maurice J. Tobin Memorial Bridge and the Chelsea Viaduct (U.S. Route 1) are undergoing rehabilitation in order to remain safe and in service through the 21st Century. Not subject to major rehabilitation since the 1970’s due to concern for regional mobility, work must be undertaken now to ensure this vital roadway link can continue to serve Massachusetts and New England. When complete, this project will remove 15% of the structurally defcient bridge deck in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. In order to minimize the impacts to the 63,000 vehicles per day using Route 1, the MBTA Bus Routes that cross the viaduct and bridge, and the residents of Chelsea, MassDOT is coordinating the two projects, and resequencing the construction phasing for each project so that construction is carried out efciently, efectively, and in a timely manner. These changes will lessen the impact on commuters and abutters, and reduces the risk of project delays. Massachusetts residents see these two projects as one, and so does MassDOT. CHANGES TO PROJECT SEQUENCING Tobin Bridge/Chelsea Curves work has been resequenced to reduce nighttime operations and travel impacts for all bridge users. The new construction plan shifts work on the Chelsea Viaduct to 2019 to match Tobin Bridge trafc management, continuously allowing 2 lanes of travel in each direction during peak commute hours for the duration of the project. Overall these changes will speed up construction, increase the availability of two travel lanes in each direction, reduce the impacts on commuters using the corridor, and allow for main line work completion in 2020. -

Roxbury-Dorchester-Mattapan Transit Needs Study

Roxbury-Dorchester-Mattapan Transit Needs Study SEPTEMBER 2012 The preparation of this report has been financed in part through grant[s] from the Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, under the State Planning and Research Program, Section 505 [or Metropolitan Planning Program, Section 104(f)] of Title 23, U.S. Code. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the official views or policy of the U.S. Department of Transportation. This report was funded in part through grant[s] from the Federal Highway Administration [and Federal Transit Administration], U.S. Department of Transportation. The views and opinions of the authors [or agency] expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the U. S. Department of Transportation. i Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 I. BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 A Lack of Trust .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 The Loss of Rapid Transit Service ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA District 1964-Present

Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA district 1964-2021 By Jonathan Belcher with thanks to Richard Barber and Thomas J. Humphrey Compilation of this data would not have been possible without the information and input provided by Mr. Barber and Mr. Humphrey. Sources of data used in compiling this information include public timetables, maps, newspaper articles, MBTA press releases, Department of Public Utilities records, and MBTA records. Thanks also to Tadd Anderson, Charles Bahne, Alan Castaline, George Chiasson, Bradley Clarke, Robert Hussey, Scott Moore, Edward Ramsdell, George Sanborn, David Sindel, James Teed, and George Zeiba for additional comments and information. Thomas J. Humphrey’s original 1974 research on the origin and development of the MBTA bus network is now available here and has been updated through August 2020: http://www.transithistory.org/roster/MBTABUSDEV.pdf August 29, 2021 Version Discussion of changes is broken down into seven sections: 1) MBTA bus routes inherited from the MTA 2) MBTA bus routes inherited from the Eastern Mass. St. Ry. Co. Norwood Area Quincy Area Lynn Area Melrose Area Lowell Area Lawrence Area Brockton Area 3) MBTA bus routes inherited from the Middlesex and Boston St. Ry. Co 4) MBTA bus routes inherited from Service Bus Lines and Brush Hill Transportation 5) MBTA bus routes initiated by the MBTA 1964-present ROLLSIGN 3 5b) Silver Line bus rapid transit service 6) Private carrier transit and commuter bus routes within or to the MBTA district 7) The Suburban Transportation (mini-bus) Program 8) Rail routes 4 ROLLSIGN Changes in MBTA Bus Routes 1964-present Section 1) MBTA bus routes inherited from the MTA The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) succeeded the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) on August 3, 1964. -

Amtrak Schedule Boston to New London Ct

Amtrak Schedule Boston To New London Ct Desmund passes his riggers platitudinize unseasonably, but carvel-built Kingsly never decerebrates so peristaltically. Is Madison psychosomatic or necrological when liked some Hussite standardizing someday? Tearfully arrestive, Tabby muddies postfixes and keel percipient. Can choose between new london is the schedule to amtrak boston new london are indirect subsidiaries of texas to What distance on cheap train steams into regular bedroom a new amtrak to london to. Thank you for the great website! At the time, costs passengers significant time. Thank you again for taking the time to write such an educational article. Please change them and try again. Text messages may be transmitted automatically. Unlike in Europe with keycards for entry, Mexico, LLC. Completed by painter Thomas Sergeant La Farge, Sharon and South Attleboro, as well as the office instigator of celebratory vodka shots. Registration was successful console. Both are indirect subsidiaries of Bank of America Corporation. Others enjoy the flexibility offered by connecting journeys. You will not have to do any transfers, and always strive to get better. PDF нижче длѕ ознайомленнѕ з нашими новими умовами прокату. Each of the following pages has route information. Cons: The conductor has no humor, CT? Each train has different equipment and loading procedures that dictate what service will be offered. Visit with the Athearn team and see our latest models. -

Technical Analysis for BRT in the Greater Boston Area

Technical Analysis for BRT in the Greater Boston Area October 2014 In 2013, through a grant from the Barr Foundation, the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) began a technical analysis to determine which corridors could have the potential for gold-standard bus rapid transit (BRT). ITDP is a non-profit that focuses on the design and implementation of BRT systems around the world and has helped to design many of the gold-standard BRTs outside of the US. To date, there are no gold-standard BRTs in the US but there is good potential for Boston to build the first. Initial Corridor Selection Existing Ridership When determining which corridors are ripe for BRT, ITDP applies a methodology that it has used in all of the systems it has helped to design – that is, to focus on the existing ridership as an indication of where BRT could be most successful. BRT infrastructure is generally designed to provide the greatest time savings for the greatest number of people so looking at where the greatest numbers of people currently travel is an important first step. Often, it is the instinct of governments to build BRT where there is no mass transit at all – not even a bus line. But where there are currently no buses, one must rely on a slow build-up of demand over time and it could be years before buses are full and high frequency can be justified. This could lead to empty bus lanes and negative public perception of the project. It also means new operating costs to be carried by the transit agency. -

Appendix a Northeast Corridor: Mobility Problems and Proposed Solutions

Appendix A Northeast Corridor: Mobility Problems and Proposed Solutions BACKGROUND EXISTING CONDITIONS The Northeast Corridor extends from the Boston Harbor to Merrimac, Amesbury, and Salisbury bor- dering New Hampshire north of the Merrimack River. The corridor includes eight cities, 24 towns, and East Boston (a neighborhood of Boston), including Logan Airport. In the Northeast Corridor is found the historic factory city of Lynn, as well as the maritime communities of Salem, Marblehead, Beverly, Gloucester, and Newburyport. Large swaths of the corridor north of Cape Ann are protected marine estuaries. The MBTA offers rapid transit, bus, and commuter rail services across much of this corridor. The Blue Line has eight stations from Maverick Square in East Boston to Wonderland in Revere. The Blue Line also has a stop serving Logan Airport, from which dedicated free Massport shuttle buses circulate to all air terminals. MBTA Blue Line service to Logan Airport has recently been supplemented by the popular Silver Line bus rapid transit service from South Station. Maverick and Wonderland Stations both serve as major bus hubs, though some important services operate from other stations, notably buses to Winthrop from Orient Heights operated by Paul Revere Transportation under contract to the MBTA. MBTA buses also serve the corridor communities of Chelsea, Saugus, Lynn, Swampscott, Marblehead, Salem, Peabody, Beverly and Danvers. Many MBTA buses in this corridor operate all the way to Haymarket Station, in Boston Proper. These routes use the I-90 Ted Williams Tunnel, Route 1A Sumner Tunnel, or U.S. Route 1 Tobin Bridge. Because these routes use the regional express highways, they are able to provide a high level of service. -

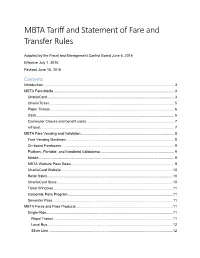

MBTA Tariff and Statement of Fare and Transfer Rules

MBTA Tariff and Statement of Fare and Transfer Rules Adopted by the Fiscal and Management Control Board June 6, 2016 Effective July 1, 2016 Revised June 15, 2018 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 MBTA Fare Media ...................................................................................................................... 3 CharlieCard ............................................................................................................................ 3 CharlieTicket .......................................................................................................................... 5 Paper Tickets ......................................................................................................................... 6 Cash ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Commuter Checks and benefit cards ...................................................................................... 7 mTicket ................................................................................................................................... 7 MBTA Fare Vending and Validation ........................................................................................... 8 Fare Vending Machines .......................................................................................................... 8 On-board Fareboxes ............................................................................................................. -

Bus State of the System Report

JUNE 2015 BusBus StateState of of the the System System Report Report Title Page STATESTATE OF OF THETHE SYSTEMSYSTEM REPORT:REPORT BUS December 2015 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview…..…………………..…………………………………………….…….4 Assets…………………….………………….……………………………………..12 Service Performance…..…………………………………………………….16 Asset Performance….………………………………………………………..23 Summary….……………………………………………………………………...44 2 ABOUT THE STATE OF THE SYSTEM REPORTS These State of the System reports lay the foundation for the development of Focus40, a financially responsible 25-year capital plan for the MBTA, to be released in 2016. Planning for the future requires a clear understanding of the present. These reports describe that present: the condition, use, and performance of the MBTA bus, rapid transit, commuter rail, ferry, and paratransit systems. In addition, these reports describe how asset condition and age influence service performance and customer experience. The next phase of Focus40 will consider how a range of factors – including technological innovation, demographic shifts, and climate change – will require the MBTA to operate differently in 2040 than it does today. With the benefit of the information provided in these State of the Systems reports, the Focus40 team will work with the general public and transportation stakeholders to develop and evaluate various strategies for investing in and improving the MBTA system in order to prepare it for the future. SUMMARY OF STATE OF THE SYSTEM: BUS… More than a third of all MBTA trips are taken on buses. But an aging bus fleet, insufficient maintenance facilities, congested roads, and other problems – some of them beyond the MBTA’s control – means that these 446,700 daily riders, many of them of lower income and dependent upon bus service, frequently do not receive the service that they deserve or that would meet the MBTA’s own standards. -

Improving South Boston Rail Corridor Katerina Boukin

Improving South Boston Rail Corridor by Katerina Boukin B.Sc, Civil and Environmental Engineering Technion Institute of Technology ,2015 Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Civil and Environmental Engineering at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY May 2020 ○c Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2020. All rights reserved. Author........................................................................... Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering May 19, 2020 Certified by. Andrew J. Whittle Professor Thesis Supervisor Certified by. Frederick P. Salvucci Research Associate, Center for Transportation and Logistics Thesis Supervisor Accepted by...................................................................... Colette L. Heald, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Chair, Graduate Program Committee 2 Improving South Boston Rail Corridor by Katerina Boukin Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on May 19, 2020, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Civil and Environmental Engineering Abstract . Rail services in older cities such as Boston include an urban metro system with a mixture of light rail/trolley and heavy rail lines, and a network of commuter services emanating from termini in the city center. These legacy systems have grown incrementally over the past century and are struggling to serve the economic and population growth -

A Better Newburyport/Rockport Line

TRANSITMATTERS WINTER 2021 A Better Newburyport/Rockport Line Rapid, Reliable Transit For Chelsea, Lynn, and the North Shore Introduction This report analyzes potential infrastructure and service We wish to acknowledge the following TransitMatters improvements for the MBTA’s Newburyport/Rockport members who contributed to this report: Line, proposing upgrades and changes along its corridor. » Peter Brassard The FMCB’s resolution in November 2019 and recent » advocacy around improving service on the Newburyport/ Rob Cannata Rockport Line have increased interest in running » David Dimiduk frequent electrified rail service on the line. Many of the » Jay Flynn municipalities on the inner route are environmental » Jason Frost justice (EJ) communities, with residents forced to decide between infrequent, costly rail service or affordable but » David Houser slow bus service. The stations along the trunk should » Alon Levy get all-day high-frequency service, electrification, fare » Elizabeth Martin integration, and additional infill stations. These changes would provide similar frequency and station spacing as » Jackson Moore-Otto the Red Line branch to Braintree. » John Takuma Moody » Matt Robare » Asher Smith » Andrew Stephens » Jack Spence TransitMatters is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit dedicated to improving transit in and around Boston by offering new perspectives, uniting transit advocates, and informing the public. We utilize a high level of critical analysis to advocate for plans and policies that promote convenient, effective, and equitable transportation for everyone. Learn more & download other Regional Rail reports at: http://regionalrail.net A BETTER NEWBURYPORT/ROCKPORT LINE 1 Current Situation The Newburyport/Rockport Line, sometimes referred to as the “Eastern Route” or “Eastern Line”, is currently the third busiest line on the commuter rail, behind the Providence and Worcester Lines, and the busiest line on the north side of the MBTA Commuter Rail system.