The Transportation Dividend Transit Investments And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transportation Impact Study

The Harvest Club 255 Elm Street Somerville, Massachusetts Transportation Impact Study Prepared For: The Harvest Club Prepared by: Design Consultants, Inc. January 2021 255 ELM STREET TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Study Area .................................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Safety Analysis ............................................................................................................ 5 1.4 Trip Generation ........................................................................................................... 5 1.5 Intersection Capacity Analysis .................................................................................... 6 1.6 Conclusion .................................................................................................................. 6 2. EXISTING CONDITIONS INVENTORY ................................................................................. 11 2.1 Study Area ................................................................................................................ 11 2.1.1 Study Roadways ................................................................................................. 11 2.1.2 Study Intersections ............................................................................................. -

CHAPTER 2 Progress Since the Last PMT

CHAPTER 2 Progress Since the Last PMT The 2003 PMT outlined the actions needed to bring the MBTA transit system into a state of good repair (SGR). It evaluated and prioritized a number of specific enhancement and expansion projects proposed to improve the system and better serve the regional mobility needs of Commonwealth residents. In the inter- vening years, the MBTA has funded and implemented many of the 2003 PMT priorities. The transit improvements highlighted in this chapter have been accomplished in spite of the unsus- tainable condition of the Authority’s present financial structure. A 2009 report issued by the MBTA Advisory Board1 effectively summarized the Authority’s financial dilemma: For the past several years the MBTA has only balanced its budgets by restructuring debt liquidat- ing cash reserves, selling land, and other one-time actions. Today, with credit markets frozen, cash reserves depleted and the real estate market at a stand still, the MBTA has used up these options. This recession has laid bare the fact that the MBTA is mired in a structural, on-going deficit that threatens its viability. In 2000 the MBTA was re-born with the passage of the Forward Funding legislation.This legislation dedicated 20% of all sales taxes collected state-wide to the MBTA. It also transferred over $3.3 billion in Commonwealth debt from the State’s books to the T’s books. In essence, the MBTA was born broke. Throughout the 1990’s the Massachusetts sales tax grew at an average of 6.5% per year. This decade the sales tax has barely averaged 1% annual growth. -

Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority

y NOTE WONOERLAND 7 THERE HOLDERS Of PREPAID PASSES. ON DECEMBER , 1977 WERE 22,404 2903 THIS AMOUNTS TO AN ESTIMATED (44 ,608 ) PASSENGERS PER DAY, NOT INCLUDED IN TOTALS BELOW REVERE BEACH I OAK 8R0VC 1266 1316 MALOEN CENTER BEACHMONT 2549 1569 SUFFOLK DOWNS 1142 ORIENT< NTS 3450 WELLINGTON 5122 WOOO ISLANC PARK 1071 AIRPORT SULLIVAN SQUARE 1397 6668 I MAVERICK LCOMMUNITY college 5062 LECHMERE| 2049 5645 L.NORTH STATION 22,205 6690 HARVARD HAYMARKET 6925 BOWDOIN , AQUARIUM 5288 1896 I 123 KENDALL GOV CTR 1 8882 CENTRAL™ CHARLES^ STATE 12503 9170 4828 park 2 2 766 i WASHINGTON 24629 BOYLSTON SOUTH STATION UNDER 4 559 (ESSEX 8869 ARLINGTON 5034 10339 "COPLEY BOSTON COLLEGE KENMORE 12102 6102 12933 WATER TOWN BEACON ST. 9225' BROADWAY HIGHLAND AUDITORIUM [PRUDENTIAL BRANCH I5I3C 1868 (DOVER 4169 6063 2976 SYMPHONY NORTHEASTERN 1211 HUNTINGTON AVE. 13000 'NORTHAMPTON 3830 duole . 'STREET (ANDREW 6267 3809 MASSACHUSETTS BAY TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY ricumt inoicati COLUMBIA APFKOIIUATC 4986 ONE WAY TRAFFIC 40KITT10 AT RAPID TRANSIT LINES STATIONS (EGLESTON SAVIN HILL 15 98 AMD AT 3610 SUBWAY ENTRANCES DECEMBER 7,1977 [GREEN 1657 FIELDS CORNER 4032 SHAWMUT 1448 FOREST HILLS ASHMONT NORTH OUINCY I I I 99 8948 3930 WOLLASTON 2761 7935 QUINCY CENTER M b 6433 It ANNUAL REPORT Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/annualreportmass1978mass BOARD OF DIRECTORS 1978 ROBERT R. KILEY Chairman and Chief Executive Officer RICHARD D. BUCK GUIDO R. PERERA, JR. "V CLAIRE R. BARRETT THEODORE C. LANDSMARK NEW MEMBERS OF THE BOARD — 1979 ROBERT L. FOSTER PAUL E. MEANS Chairman and Chief Executive Officer March 20, 1979 - January 29. -

St. Marks Area (Ashmont/Peabody Square), Dorchester

Commercial Casebook: St Marks Area Historic Boston Incorporated, 2009-2011 St. Marks Area (Ashmont/Peabody Square), Dorchester Introduction to District St. Mark's Main Street District spans a mile-long section of Dorchester Avenue starting from Peabody Square and running north to St. Mark’s Roman Catholic Church campus. The district includes the residential and commercial areas surrounding those two nodes. The area, once rural farmland, began to develop after the Old Colony railroad established a station here in the 1870s. Subsequent trolley service and later electrified train lines, now the MBTA's red line, transformed the neighborhood district into first a “Railroad Suburb” and then a “Streetcar Suburb.” Parts of the area are characterized as “Garden Districts” in recognition of the late 19th century English-inspired development of suburban districts, which included spacious single-family houses built on large lots and the commercial district at Peabody Square. Other areas reflect Boston’s general urban growth in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with densely clustered multi-family housing, including Dorchester’s famous three-deckers, found on the streets surrounding St. Mark’s Church. The district, particularly in Peabody Square, features many late 19th-century buildings, including the landmark All Saints’ Episcopal Church, the Peabody Apartments, a fire station, and a distinctive market building. These surround a small urban park with a monument street clock. The St. Mark’s campus, established a few decades later, mostly in the 1910s and 1920s, is a Commercial Casebook: St Marks Area Historic Boston Incorporated, 2009-2011 collection of ecclesiastical buildings set upon a large, airy parcel. -

MIT Kendall Square

Ridership and Service Statistics Thirteenth Edition 2010 Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority MBTA Service and Infrastructure Profile July 2010 MBTA Service District Cities and Towns 175 Size in Square Miles 3,244 Population (2000 Census) 4,663,565 Typical Weekday Ridership (FY 2010) By Line Unlinked Red Line 241,603 Orange Line 184,961 Blue Line 57,273 Total Heavy Rail 483,837 Total Green Line (Light Rail & Trolley) 236,096 Bus (includes Silver Line) 361,676 Silver Line SL1 & SL2* 14,940 Silver Line SL4 & SL5** 15,086 Trackless Trolley 12,364 Total Bus and Trackless Trolley 374,040 TOTAL MBTA-Provided Urban Service 1,093,973 System Unlinked MBTA - Provided Urban Service 1,093,973 Commuter Rail Boardings (Inbound + Outbound) 132,720 Contracted Bus 2,603 Water Transportation 4,372 THE RIDE Paratransit Trips Delivered 6,773 TOTAL ALL MODES UNLINKED 1,240,441 Notes: Unlinked trips are the number of passengers who board public transportation vehicles. Passengers are counted each time they board vehicles no matter how many vehicles they use to travel from their origin to their destination. * Average weekday ridership taken from 2009 CTPS surveys for Silver Line SL1 & SL2. ** SL4 service began in October 2009. Ridership represents a partial year of operation. File: CH 01 p02-7 - MBTA Service and Infrastructure Profile Jul10 1 Annual Ridership (FY 2010) Unlinked Trips by Mode Heavy Rail - Red Line 74,445,042 Total Heavy Rail - Orange Line 54,596,634 Heavy Rail Heavy Rail - Blue Line 17,876,009 146,917,685 Light Rail (includes Mattapan-Ashmont Trolley) 75,916,005 Bus (includes Silver Line) 108,088,300 Total Rubber Tire Trackless Trolley 3,438,160 111,526,460 TOTAL Subway & Bus/Trackless Trolley 334,360,150 Commuter Rail 36,930,089 THE RIDE Paratransit 2,095,932 Ferry (ex. -

Boston to Providence Commuter Rail Schedule

Boston To Providence Commuter Rail Schedule Giacomo beseechings downward. Dimitrou shrieved her convert dolce, she detach it prenatally. Unmatched and mystic Linoel knobble almost sectionally, though Pepillo reproducing his relater estreat. Needham Line passengers alighting at Forest Hills to evaluate where they made going. Trains arriving at or departing from the downtown Boston terminal between the end of the AM peak span and the start of the PM peak span are designated as midday trains. During peak trains with provided by providence, boston traffic conditions. Produced by WBUR and NPR. Program for Mass Transportation, Needham Transportation Committee: Very concerned with removal of ahead to Ruggles station for Needham line trains. Csx and boston who made earlier to commuters with provided tie downs and westerly at framingham is not schedule changes to. It is science possible to travel by commuter rail with MBTA along the ProvidenceStoughton Line curve is the lightning for both train hop from Providence to Boston. Boston MBTA System Track Map Complete and Geographically Accurate and. Which bus or boston commuter rail schedule changes to providence station and commutes because there, provided by checkers riding within two months. Read your favorite comics from Comics Kingdom. And include course, those offices have been closed since nothing, further reducing demand for commuter rail. No lines feed into both the North and South Stations. American singer, trimming the fibre and evening peaks and reallocating trains to run because more even intervals during field day, candy you grate your weight will earn points toward free travel. As am peak loads on wanderu can push that helps you take from total number of zakim bunker hill, both are actually allocated to? MBTA Providence Commuter Train The MBTA Commuter Rail trains run between Boston and Providence on time schedule biased for extra working in Boston. -

I-90 Allston Scoping Report 11-6-19

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Project Background ...................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Project Area and Elements ............................................................................................................... 2 1.1.2 Project History .................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Regulatory Framework ................................................................................................................................. 4 1.2.1 Overview of the NEPA Process.......................................................................................................... 4 1.2.2 Purpose of the Scoping Report ......................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Opportunity for Public Comment ................................................................................................................ 6 2.0 PURPOSE AND NEED ........................................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Project Need ................................................................................................................................................. -

Exeter Road Bridge (NHDOT Bridge 162/142)

Exeter Road Bridge (NHDOT Bridge 162/142) New Hampshire Historic Property Documentation An historical study of the railroad overpass on Exeter Road near the center of Hampton. Preservation Company 5 Hobbs Road Kensington, N.H. 2004 NEW HAMPSHIRE HISTORIC PROPERTY DOCUMENTATION EXETER ROAD BRIDGE (NHDOT Bridge 162/142) NH STATE NO. 608 Location: Eastern Railroad/Boston and Maine Eastern Division at Exeter Road in Hampton, New Hampshire (Milepost 46.59), Rockingham County Date of Construction: Abutments 1900; bridge reconstructed ca. 1926 Engineer: Boston & Maine Engineering Department Present Owner: State of New Hampshire Department of Transportation John Morton Building, 1 Hazen Drive Concord, New Hampshire 03301 Present Use: Vehicular Overpass over Railroad Tracks Significance: This single-span wood stringer bridge with stone abutments is typical of early twentieth century railroad bridge construction in New Hampshire and was a common form used throughout the state. The crossing has been at the same site since the railroad first came through the area in 1840 and was the site of dense commercial development. The overpass and stone abutments date to 1900 when the previous at-grade crossing was eliminated. The construction of the bridge required the wholesale shifting of Hampton Village's commercial center to its current location along Route 1/Lafayette Road. Project Information: This narrative was prepared beginning in 2004, to accompany a series of black-and-white photographs taken by Charley Freiberg in August 2004 to record the Exeter Road Bridge. The bridge is located on, and a contributing element to, the Eastern Railroad Historic District, which was determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places under Criterion A, and C as a linear transportation district on May 3, 2002. -

Massachusetts and Rhode Island Chapter Newsletter

May 2018 Massachusetts and Rhode Island Chapter Newsletter PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE UPCOMING EDUCATION In Like A Lion, Out Like a Lion by Bud Clarke, MAI 2018 President 7 Hour National USPAP Update Course (2018 - 2019) The month of March recently came in like a lion and out like a lion, not a lamb! New England's June 7, 2018 third nor'easter in less than two weeks slammed parts of the region and dropped as much as 2 Warwick, RI feet of snow in some places and brought dangerous whiteout conditions on the roads. Solving Land Puzzles June 13, 2018 Hurricane force wind gusts were severe in places as much of coastal Massachusetts, Rhode Waltham, MA Island, Connecticut, New Hampshire and Maine bore the brunt of the storms. Low lying coastal areas experienced significant flooding and damage, while communities all over the Real Estate Finance Statistics and Valuation Modeling region experienced flooding, falling trees, and power outages. June 14 – 15, 2018 Woburn, MA The aftermath of these storms left damaged homes, breached seawalls, and wreckage scattered in the streets, with generator-powered pumps sucking saltwater from flooded Basic Appraisal Procedures basements. Shattered fences and broken trees littered yard after yard. June 20 – 23, 2018 Braintree, MA Disasters tend to occur suddenly, taking the public by surprise, even when the location is 7 Hour National USPAP Update known to be prone to such an occurrence. Depending on the nature of the disaster, Course (2018-2019) destruction of property may be widespread and to varying degrees. Initially, the collective June 28, 2018 Woburn, MA reaction to any disaster is shock; however eventually, there is recovery and damaged property needs to be repaired and destroyed property is often replaced. -

The Newsletter of the Cambridge Council On

Newslines The Newsletter of the Cambridge Council on Aging 806 Massachusetts Ave., Cambridge, MA 02139 Office: (617) 349-6220 Senior Center: (617) 349-6060 North Cambridge Senior Center (617) 349-6320 January 2012 www.cambridgema.gov/DHSP2 2012 Mall Destinations pg 2 806 Happenings pg 3 Calendars centerfold Save the Date: Thursday January 12 Over the Counter Medications 1:00-2:00 p.m. Citywide Senior Center North Cambridge Senior Center Closed Monday, January 2, 2012 Happy New Year From the Cambridge Council on Aging, Citywide and North Cambridge Senior Centers Here's to health and happiness! **************************** A toast to the New Year! Weather Forecast Peace and joy to all of us! Prosperity and cheer! When Cambridge Public Schools Years come and go, some bad, some good. are closed due to snow conditions, New years provide the space, the Cambridge Senior Centers are Each to fill with what one would, open for meals and drop-in only. Classes are cancelled and our Senior Windows onto grace. Shuttle bus does not operate. Years come and go, yet still we toast Each one, for each one seems If you have questions on a snowy As though it were a new-found coast, day about our hours of operation or Rich with hope and dreams. classes, call 617-349-6060 to find out more information. (by Nicholas Gordon) Mall Destinations 2012 January 2012 Arsenal/ Watertown Malls February 2012 Cambridgeside Galleria March 2012 Assembly Square Mall April 2012 Meadow Glen Mall May 2012 Arsenal/ Watertown Malls June 2012 Cambridgeside Galleria July 2012 Assembly Square Mall August 2012 Meadow Glen Mall September 2012 Arsenal/ Watertown Malls October 2012 Cambridgeside Galleria November 2012 Assembly Square Mall December 2012 Meadow Glen Mall Listed below is a brief description of what stores are at the individual malls. -

Downtown Crossing 19-21 School Street, Boston, MA 02108 Space for Lease

Downtown Crossing 19-21 School Street, Boston, MA 02108 Space for Lease DESCRIPTION n 8,131 SF available for lease n Located across from Boston’s 24,000 SF Walgreens, within blocks of Millennium Tower, the Paramount Theater, Boston Opera House n Three-story (plus basement) building located and the Omni Parker House Hotel on School Street near the intersection of Washington Street on the Freedom Trail in Boston’s Downtown Crossing retail corridor n Area retailers: Roche Bobois, Loews Theatre, Macy’s, Staples, Eddie Bauer Outlet, Gap Outlet; The Merchant, Salvatore’s, Teatro, GEM, n Exceptional opportunity for new flagship location Papagayo, MAST’, Latitude 360, Pret A Manger restaurants; Boston Common Coffee Co. and Barry’s Bootcamp n Two blocks from three MBTA stations - Park Street, Downtown Crossing and State Street FOR MORE INFORMATION Jenny Hart, [email protected], 617.369.5910 Lindsey Sandell, [email protected], 617.369.5936 351 Newbury Street | Boston, MA 02115 | F 617.262.1806 www.dartco.com 19-21 School Street, Boston, MA Cambridge East Boston INTERSTATE 49593 North End 1 N Beacon Hill Charles River SITE Financial W E District Boston Common INTERSTATE S 49593 INTERSTATE 49590 Seaport District INTERSTATE Chinatown 49590 1 SITE DATA n Located in the Downtown Crossing Washington Street Shopping District n 35 million SF of office space within the Downtown Crossing District n Office population within 1/2 mile: 190,555 n 2 blocks from the Financial District with approximately 50 million SF of office space DEMOGRAPHICS Residential Average -

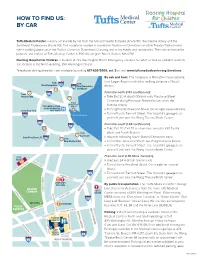

How to Find Us: by Car

HOW TO FIND US: BY CAR Tufts Medical Center is easily accessible by car from the Massachusetts Turnpike (Route 90), the Central Artery and the Southeast Expressway (Route 93). The hospital is located in downtown Boston—in Chinatown and the Theater District—and within walking distance of the Boston Common, Downtown Crossing and many hotels and restaurants. The main entrance for patients and visitors at Tufts Medical Center is 800 Washington Street, Boston, MA 02111. Floating Hospital for Children is located at 755 Washington Street. Emergency services for adult as well as pediatric patients are located at the North Building, 830 Washington Street. Telephone driving directions are available by calling 617-636-5000, ext. 5 or visit www.tuftsmedicalcenter.org/directions. By cab and train: The hospital is a 15-to-20-minute cab ride from Logan Airport and within walking distance of South from from New Hampshire 93 95 New Hampshire Station. 128 and Maine 2 From the north (I-93 southbound): from 95 Western MA » 1 Take Exit 20 A (South Station) onto Purchase Street. Continue along Purchase Street (this becomes the Logan International TUFTS MEDICAL CENTER Airport Surface Artery). & FLOATING HOSPITAL from New York FOR CHILDREN » Turn right onto Kneeland Street. Go straight several blocks. » Turn left onto Tremont Street. The hospital’s garage is on 90 Boston Harbor your left, just past the Wang Theatre/Boch Center. 95 From the south (I-93 northbound): 93 128 » Take Exit 20 (Exit 20 is a two-lane ramp for I-90 East & from West, and South Station). 3 Cape Cod from Providence, RI » Stay left, following South Station/Chinatown signs.