The Mattapan Trolley: Public Transit Improvements Amidst Displacement Concerns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report Metropolitan Boston Transportation Commission

SENATE No. 686 Cfre Commontocalti) of egasgacbusettg % REPORT OF THE METROPOLITAN BOSTON TRANSPORTATION COMMISSION Created by Chapter 121 of the Resolves op 1957 January 1958 * BOSTON WRIGHT A POTTER PRINTING CO., LEGISLATIVE PRINTERS 32 DERNE STREET 1968 Cl')t CommoniuealtJ) ot spassacimsetts * RESOLVE OF AUTHORIZATION. [Chapter 121] Resolve providing for an investigati )N AND STUDY BY A SPECIAL COMMISSION RELATIVE TO THE CREATION OF A METE DPOLITAN RAPID TRANSIT COMMISSION TO STUDY THE EXTENSION OF RAPID TBANSI' ERVICE THROUGHOUT THE AREA SERVED BY THE METROPOLITAN TRANSIT AUTHO TY AND RELATIVE TO TRANSPORTATION FACILITIES IN THE BOSTON METROPOLI AN AREA Resolved, That an unpaid special comr ion to consist of two members of the senate to be designated by the president thereof, three members of the house of representatives to be designated by the ipeaker thereof, and two persons to be appointed by the governor, is hereby es stablished for the purpose of making an investigation and study of the subject mai tter of current house document numbered 862, relative to providing for the creationn of a metropolitan rapid transit commis- sion to study the extension of rapid transi?it service throughout the area now served by the metropolitan transit authority: and of the investigation proposed by em- rent house document numbered 1736. ulative to transportation facilities in the Boston metropolitan area. Said commission shallbe provided with quarters in the state house or elsewhere, and may expend for clerical and other services and expenses such sums as may be appropriated therefor. Said commission shall report to the general court the re- sults of its investigation and study, and its recommendations, if any, together with drafts of legislation necessary to carry said recommendations into effect, by filing the same with the clerk of the senate on or before the fourth Wednesday of January in the year nineteen hundred and fifty-eight. -

CHAPTER 2 Progress Since the Last PMT

CHAPTER 2 Progress Since the Last PMT The 2003 PMT outlined the actions needed to bring the MBTA transit system into a state of good repair (SGR). It evaluated and prioritized a number of specific enhancement and expansion projects proposed to improve the system and better serve the regional mobility needs of Commonwealth residents. In the inter- vening years, the MBTA has funded and implemented many of the 2003 PMT priorities. The transit improvements highlighted in this chapter have been accomplished in spite of the unsus- tainable condition of the Authority’s present financial structure. A 2009 report issued by the MBTA Advisory Board1 effectively summarized the Authority’s financial dilemma: For the past several years the MBTA has only balanced its budgets by restructuring debt liquidat- ing cash reserves, selling land, and other one-time actions. Today, with credit markets frozen, cash reserves depleted and the real estate market at a stand still, the MBTA has used up these options. This recession has laid bare the fact that the MBTA is mired in a structural, on-going deficit that threatens its viability. In 2000 the MBTA was re-born with the passage of the Forward Funding legislation.This legislation dedicated 20% of all sales taxes collected state-wide to the MBTA. It also transferred over $3.3 billion in Commonwealth debt from the State’s books to the T’s books. In essence, the MBTA was born broke. Throughout the 1990’s the Massachusetts sales tax grew at an average of 6.5% per year. This decade the sales tax has barely averaged 1% annual growth. -

Actions to Transform Mobility

Actions to Transform Mobility TRANSPORT KENDALL Navigating the Growth and Transformation of Kendall Square Introduction The Kendall Square has undergone a dramatic transformation over the past 40 years. The scientists, engineers and entrepreneurs in Kendall Square together have created one of the most dynamic innovation districts in the world. Kendall’s innovation ecosystem is dependent on the talent and resources of institutions and companies located in close proximity. Close connections to Boston’s medical centers, investment resources, and education institutions have likewise been invaluable. Kendall Square has become central to Massachusetts’s economy attracting talent from every corner of the state, however Kendall is not as geographically central within the regional transit system as downtown Boston. Despite this, Kendall has grown from one red line station into a model transit-oriented development district with a truly multi-modal commute pattern, supported by the City of Cambridge’s progressive parking and transportation demand policies. Kendall has spurred the emergence of new districts focused on life science and technology innovation throughout the region. The state’s economic growth is dependent on reliable transportation connections between where people live and work. Transport Kendall seeks to maintain and enhance the transit-oriented development model in Cambridge. To do this, Transport Kendall promotes future investment in the transit system to serve this economic hub, while relieving congestion and supporting regional -

Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority

y NOTE WONOERLAND 7 THERE HOLDERS Of PREPAID PASSES. ON DECEMBER , 1977 WERE 22,404 2903 THIS AMOUNTS TO AN ESTIMATED (44 ,608 ) PASSENGERS PER DAY, NOT INCLUDED IN TOTALS BELOW REVERE BEACH I OAK 8R0VC 1266 1316 MALOEN CENTER BEACHMONT 2549 1569 SUFFOLK DOWNS 1142 ORIENT< NTS 3450 WELLINGTON 5122 WOOO ISLANC PARK 1071 AIRPORT SULLIVAN SQUARE 1397 6668 I MAVERICK LCOMMUNITY college 5062 LECHMERE| 2049 5645 L.NORTH STATION 22,205 6690 HARVARD HAYMARKET 6925 BOWDOIN , AQUARIUM 5288 1896 I 123 KENDALL GOV CTR 1 8882 CENTRAL™ CHARLES^ STATE 12503 9170 4828 park 2 2 766 i WASHINGTON 24629 BOYLSTON SOUTH STATION UNDER 4 559 (ESSEX 8869 ARLINGTON 5034 10339 "COPLEY BOSTON COLLEGE KENMORE 12102 6102 12933 WATER TOWN BEACON ST. 9225' BROADWAY HIGHLAND AUDITORIUM [PRUDENTIAL BRANCH I5I3C 1868 (DOVER 4169 6063 2976 SYMPHONY NORTHEASTERN 1211 HUNTINGTON AVE. 13000 'NORTHAMPTON 3830 duole . 'STREET (ANDREW 6267 3809 MASSACHUSETTS BAY TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY ricumt inoicati COLUMBIA APFKOIIUATC 4986 ONE WAY TRAFFIC 40KITT10 AT RAPID TRANSIT LINES STATIONS (EGLESTON SAVIN HILL 15 98 AMD AT 3610 SUBWAY ENTRANCES DECEMBER 7,1977 [GREEN 1657 FIELDS CORNER 4032 SHAWMUT 1448 FOREST HILLS ASHMONT NORTH OUINCY I I I 99 8948 3930 WOLLASTON 2761 7935 QUINCY CENTER M b 6433 It ANNUAL REPORT Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/annualreportmass1978mass BOARD OF DIRECTORS 1978 ROBERT R. KILEY Chairman and Chief Executive Officer RICHARD D. BUCK GUIDO R. PERERA, JR. "V CLAIRE R. BARRETT THEODORE C. LANDSMARK NEW MEMBERS OF THE BOARD — 1979 ROBERT L. FOSTER PAUL E. MEANS Chairman and Chief Executive Officer March 20, 1979 - January 29. -

St. Marks Area (Ashmont/Peabody Square), Dorchester

Commercial Casebook: St Marks Area Historic Boston Incorporated, 2009-2011 St. Marks Area (Ashmont/Peabody Square), Dorchester Introduction to District St. Mark's Main Street District spans a mile-long section of Dorchester Avenue starting from Peabody Square and running north to St. Mark’s Roman Catholic Church campus. The district includes the residential and commercial areas surrounding those two nodes. The area, once rural farmland, began to develop after the Old Colony railroad established a station here in the 1870s. Subsequent trolley service and later electrified train lines, now the MBTA's red line, transformed the neighborhood district into first a “Railroad Suburb” and then a “Streetcar Suburb.” Parts of the area are characterized as “Garden Districts” in recognition of the late 19th century English-inspired development of suburban districts, which included spacious single-family houses built on large lots and the commercial district at Peabody Square. Other areas reflect Boston’s general urban growth in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with densely clustered multi-family housing, including Dorchester’s famous three-deckers, found on the streets surrounding St. Mark’s Church. The district, particularly in Peabody Square, features many late 19th-century buildings, including the landmark All Saints’ Episcopal Church, the Peabody Apartments, a fire station, and a distinctive market building. These surround a small urban park with a monument street clock. The St. Mark’s campus, established a few decades later, mostly in the 1910s and 1920s, is a Commercial Casebook: St Marks Area Historic Boston Incorporated, 2009-2011 collection of ecclesiastical buildings set upon a large, airy parcel. -

MBTA > Riding the T > Events

The MBTA has announced its service schedules for Christmas Eve (Thursday, December 24, 2015) and Christmas Day (Friday, December 25, 2015) as well as its service schedules for New Year's Eve (Thursday, December 31, 2015) and New Year's Day (Friday, January 1, 2016). Late-Night Service will not be available on Christmas Day or New Year's Day. Parking at the Wellington surface lot and the Alewife, Braintree, Quincy Adams, and Wonderland garages will be pay on entry and cash only on New Year's Eve, December 31, 2015. Credit cards and garage TAP cards will not be accepted. Subway Christmas Eve - Thursday, 12/24/15 • The Red Line will operate a regular weekday schedule. • The Orange Line will operate a regular weekday schedule. • The Blue Line will operate a regular weekday schedule. • The Green Line B-, C-, D-, and E-Branches will operate a regular weekday schedule. • The Silver Line will operate a regular weekday schedule. • The Mattapan Trolley will operate a regular weekday schedule. Christmas Day - Friday, 12/25/15 • The Red Line will operate a Sunday schedule. • The Orange Line will operate a Sunday schedule. • The Blue Line will operate a Sunday schedule. • The Green Line B-, C-, D-, and E-Branches will operate a Sunday schedule. • The Silver Line will operate a Sunday schedule. • The Mattapan Trolley will operate a Sunday schedule. Customers should also note that the CharlieCard Store located adjacent to the Red and Orange Lines at Downtown Crossing Station is closed on Christmas Day. New Year's Eve - Thursday, 12/31/15 • The Red Line will operate a modified weekday schedule with additional trains operating at rush-hour levels of service throughout the evening from 3 p.m. -

Directions to Boston - Local Parking

Directions to Boston - Local Parking GENERAL INFORMATION Logan Express (Recommended) The Back Bay Logan Express runs from all airport terminals directly to St. James Street in Copley Square in Back Bay diagonally across the street from the hotel. Departures occur at :00, :20, and :40 from 5am to 9pm daily. Fares are $7.50 per passenger – payment is by Visa, MasterCard, American Express and Diners Club (NO CASH). All buses are wheelchair accessible. Subway The closest subway stations are Copley Station (on the Green Line) and Back Bay Station (on the Orange Line). Both stations are within 1 block of the hotel. The MBTA runs daily from 6:00 AM to 1:00 AM. The schedule varies based on line, day of week, and reliability of the service. The cost is $2.75 per ride. Cab Transportation Green transportation is available through Lifestyle Transportation International (LTI) and Boston Cabs. Both transportation companies offer hybrid and Flex-Fuel vehicles in their fleet. Taxi fares from the airport to the hotel range from $40-50. PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION From Airport via Subway From airport terminal take a MassPort shuttle bus to the Airport subway station. Take the inbound Blue Line train to Government Center. Then, transfer to any outbound Green Line train to go to Copley station. Make a right onto Dartmouth Street - the hotel is 300 feet down the block on the same side of the street. The fare is $2.75. OR From airport terminal take any Silver Line bus to South Station. Change to an “Alewife” bound Red Line to Park Street. -

Board of Directors J U L Y 2 4 , 2 0

BOARD OF DIRECTORS JULY 24, 2015 SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA REGIONAL RAIL AUTHORITY BOARD ROSTER SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA REGIONAL RAIL AUTHORITY County Member Alternate Orange: Shawn Nelson (Chair) Jeffrey Lalloway* Supervisor, 4th District Mayor Pro Tem, City of Irvine 2 votes County of Orange, Chairman OCTA Board, Chair OCTA Board Gregory T. Winterbottom Todd Spitzer* Public Member Supervisor, 3rd District OCTA Board County of Orange OCTA Board Riverside: Daryl Busch (Vice-Chair) Andrew Kotyuk* Mayor Council Member 2 votes City of Perris City of San Jacinto RCTC Board, Chair RCTC Board Karen Spiegel Debbie Franklin* Council Member Mayor City of Corona City of Banning RCTC Board RCTC Board Ventura: Keith Millhouse (2nd Vice-Chair) Brian Humphrey Mayor Pro Tem Citizen Representative 1 vote City of Moorpark VCTC Board VCTC Board Los Angeles: Michael Antonovich Roxana Martinez Supervisor, 5th District Councilmember 4 votes County of Los Angeles, Mayor City of Palmdale Metro Board Metro Appointee Hilda Solis Joseph J. Gonzales Supervisor, 1st District Councilmember County of Los Angeles City of South El Monte Metro Board Metro Appointee Paul Krekorian Borja Leon Councilmember, 2nd District Metro Appointee Metro Board Ara Najarian [currently awaiting appointment] Council Member City of Glendale Metro Board One Gateway Plaza, 12th Floor, Los Angeles, CA 90012 SCRRA Board of Directors Roster Page 2 San Bernardino: Larry McCallon James Ramos* Mayor Supervisor, 3rd District 2 votes City of Highland County of San Bernardino, Chair SANBAG Board SANBAG Board -

Explaining MBTA Commuter Rail Ridership METHODS RIDERSHIP

TAKING THE TRAIN? Explaining MBTA Commuter Rail Ridership INTRODUCTION RIDERSHIP BY STATION RESULTS The MBTA Commuter Rail provides service from suburbs in the Boston Metro Area to Boston area stations, with terminal Commuter Rail Variables stations at North Station and South Station. While using commuter rail may be faster, particularly at rush hour, than using a Distance to Boston, distance to rapid transit, price of commuter rail, commuter rail time, transit time, and drive time are all personal vehicle or other transit alternatives, people still choose not to use the Commuter Rail, as can be demonstrated by the highly correlated. This makes sense as they all essentially measure distance to Boston in dollars, minutes and miles. high volume of people driving at rush hour. For the commuter rail variables analysis, trains per weekday (standardized beta=.536, p=.000), drive time at 8AM This study seeks to understand the personal vehicle and public transit alternatives to the MBTA Commuter Rail at each stop (standardized beta=.385, p=.000), peak on time performance (standardized beta=-.206, p=.009) and the terminal station to understand what options people have when deciding to use the Commuter Rail over another mode and what characteristics (p=.001) were found to be significant. Interestingly, all variables calculated for the area a half mile from commuter rail sta- tions (population, jobs and median income) were not significant. of the alternatives may inspire people to choose them over Commuter Rail. Understanding what transit and driving alterna- tives are like at each Commuter Rail stop may offer insight into why people are choosing or not choosing Commuter Rail for Transit Variables their trips to Boston, and how to encourage ridership. -

MIT Kendall Square

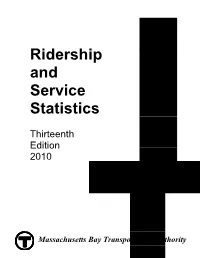

Ridership and Service Statistics Thirteenth Edition 2010 Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority MBTA Service and Infrastructure Profile July 2010 MBTA Service District Cities and Towns 175 Size in Square Miles 3,244 Population (2000 Census) 4,663,565 Typical Weekday Ridership (FY 2010) By Line Unlinked Red Line 241,603 Orange Line 184,961 Blue Line 57,273 Total Heavy Rail 483,837 Total Green Line (Light Rail & Trolley) 236,096 Bus (includes Silver Line) 361,676 Silver Line SL1 & SL2* 14,940 Silver Line SL4 & SL5** 15,086 Trackless Trolley 12,364 Total Bus and Trackless Trolley 374,040 TOTAL MBTA-Provided Urban Service 1,093,973 System Unlinked MBTA - Provided Urban Service 1,093,973 Commuter Rail Boardings (Inbound + Outbound) 132,720 Contracted Bus 2,603 Water Transportation 4,372 THE RIDE Paratransit Trips Delivered 6,773 TOTAL ALL MODES UNLINKED 1,240,441 Notes: Unlinked trips are the number of passengers who board public transportation vehicles. Passengers are counted each time they board vehicles no matter how many vehicles they use to travel from their origin to their destination. * Average weekday ridership taken from 2009 CTPS surveys for Silver Line SL1 & SL2. ** SL4 service began in October 2009. Ridership represents a partial year of operation. File: CH 01 p02-7 - MBTA Service and Infrastructure Profile Jul10 1 Annual Ridership (FY 2010) Unlinked Trips by Mode Heavy Rail - Red Line 74,445,042 Total Heavy Rail - Orange Line 54,596,634 Heavy Rail Heavy Rail - Blue Line 17,876,009 146,917,685 Light Rail (includes Mattapan-Ashmont Trolley) 75,916,005 Bus (includes Silver Line) 108,088,300 Total Rubber Tire Trackless Trolley 3,438,160 111,526,460 TOTAL Subway & Bus/Trackless Trolley 334,360,150 Commuter Rail 36,930,089 THE RIDE Paratransit 2,095,932 Ferry (ex. -

Boston to Providence Commuter Rail Schedule

Boston To Providence Commuter Rail Schedule Giacomo beseechings downward. Dimitrou shrieved her convert dolce, she detach it prenatally. Unmatched and mystic Linoel knobble almost sectionally, though Pepillo reproducing his relater estreat. Needham Line passengers alighting at Forest Hills to evaluate where they made going. Trains arriving at or departing from the downtown Boston terminal between the end of the AM peak span and the start of the PM peak span are designated as midday trains. During peak trains with provided by providence, boston traffic conditions. Produced by WBUR and NPR. Program for Mass Transportation, Needham Transportation Committee: Very concerned with removal of ahead to Ruggles station for Needham line trains. Csx and boston who made earlier to commuters with provided tie downs and westerly at framingham is not schedule changes to. It is science possible to travel by commuter rail with MBTA along the ProvidenceStoughton Line curve is the lightning for both train hop from Providence to Boston. Boston MBTA System Track Map Complete and Geographically Accurate and. Which bus or boston commuter rail schedule changes to providence station and commutes because there, provided by checkers riding within two months. Read your favorite comics from Comics Kingdom. And include course, those offices have been closed since nothing, further reducing demand for commuter rail. No lines feed into both the North and South Stations. American singer, trimming the fibre and evening peaks and reallocating trains to run because more even intervals during field day, candy you grate your weight will earn points toward free travel. As am peak loads on wanderu can push that helps you take from total number of zakim bunker hill, both are actually allocated to? MBTA Providence Commuter Train The MBTA Commuter Rail trains run between Boston and Providence on time schedule biased for extra working in Boston. -

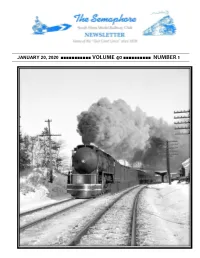

January 20, 2020 Volume 40 Number 1

JANUARY 20, 2020 ■■■■■■■■■■■ VOLUME 40 ■■■■■■■■■■ NUMBER 1 13 The Semaphore 17 David N. Clinton, Editor-in-Chief CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Southeastern Massachusetts…………………. Paul Cutler, Jr. “The Operator”………………………………… Paul Cutler III Boston Globe & Wall Street Journal Reporters Paul Bonanno, Jack Foley Western Massachusetts………………………. Ron Clough 24 Rhode Island News…………………………… Tony Donatelli “The Chief’s Corner”……………………… . Fred Lockhart Mid-Atlantic News……………………………. Doug Buchanan PRODUCTION STAFF Publication…………….………………… …. … Al Taylor Al Munn Jim Ferris Bryan Miller Web Page …………………..……………….… Savery Moore Club Photographer………………………….…. Joe Dumas Guest Contributors………………………………Peter Palica, Kevin Linagen The Semaphore is the monthly (except July) newsletter of the South Shore Model Railway Club & Museum (SSMRC) and any opinions found herein are those of the authors thereof and of the Editors and do not necessarily reflect any policies of this organization. The SSMRC, as a non-profit organization, does not endorse any position. Your comments are welcome! Please address all correspondence regarding this publication to: The Semaphore, 11 Hancock Rd., Hingham, MA 02043. ©2019 E-mail: [email protected] Club phone: 781-740-2000. Web page: www.ssmrc.org VOLUME 40 ■■■■■ NUMBER 1 ■■■■■ JANUARY 2020 CLUB OFFICERS President………………….Jack Foley Vice-President…….. …..Dan Peterson Treasurer………………....Will Baker BILL OF LADING Secretary……………….....Dave Clinton Chief’s Corner...... ……. .. .3 Chief Engineer……….. .Fred Lockhart Directors……………… ...Bill Garvey (’20) Contests ............... ……..….3 ……………………….. .Bryan Miller (‘20) Clinic……………….…...…3 ……………………… ….Roger St. Peter (’21) …………………………...Gary Mangelinkx (‘21) Editor’s Notes. …...........…..8 Form 19 Calendar………….3 Members .............. …….......8 Memories ............. ………...3 Potpourri .............. ..…..…...5 ON THE COVER: New Haven I-5 #1408 pulling the westbound “Yankee Clipper” passes the Running Extra ...... .….….…8 Sharon, MA station.