Diary of Exploration Wet Earth Colliery Volume 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North West Geography

ISSN 1476-180 North West Geography Volume 8, Number 1, 2008 North West Geography, Volume 8, 2008 1 A deeper understanding of climate induced risk to urban infrastructure: case studies of past events in Greater Manchester Nigel Lawson and Sarah Lindley Geography, School of Environment and Development The University of Manchester Email: [email protected] Abstract A detailed knowledge of past events is sometimes used to help understand and manage potential future risks. Flood risk management is one area where this has been particularly true, but the same ideas could theoretically be applied to other potential climate induced impacts in urban areas such as subsidence, sewer collapse and land movement. Greater Manchester, as the world’s first industrial city, provides an ideal case study of how such events have affected the urban infrastructure in the past. This paper reviews some of the evidence which can be gleaned from past events and also shows how the realisation of some climate-related risks in heavy modified urban environments can only be fully understood through a consideration of sub-surface as well as surface characteristics. Key words flood, subsidence, risk assessment, Greater Manchester Introduction element which is exposed. It follows, therefore, that unless Urban areas have always been prone to climate-related risks there is a connection between all three risk components, as a result of their ability to modify physical processes such there can be no risk. Using these terms, drivers of changing as drainage and heat exchange and their high concentration patterns of risk can be seen to be as much associated with of people and property. -

Electoral Review of Salford City Council

Electoral review of Salford City Council Response to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England’s consultation on Warding Patterns August 2018 1 1 Executive Summary 1.1 Salford in 2018 has changed dramatically since the city’s previous electoral review of 2002. Salford has seen a turnaround in its fortunes over recent years, reversing decades of population decline and securing high levels of investment. The city is now delivering high levels of growth, in both new housing and new jobs, and is helping to drive forward both Salford’s and the Greater Manchester economies. 1.2 The election of the Greater Manchester Mayor and increased devolution of responsibilities to Greater Manchester, and the Greater Manchester Combined Authority, is fundamentally changing the way Salford City Council works in areas of economic development, transport, work and skills, planning, policing and more recently health and social care. 1.3 Salford’s directly elected City Mayor has galvanised the city around eight core priorities – the Great Eight. Delivering against these core priorities will require the sustained commitment and partnership between councillors, partners in the private, public, community and voluntary and social enterprise sectors, and the city’s residents. This is even more the case in the light of ongoing national policy changes, the impending departure of the UK from the EU, and continued austerity in funding for vital local services. The city’s councillors will have an absolutely central role in delivering against these core priorities, working with all our partners and residents to harness the energies and talents of all of the city. -

Salford West Strategic Regeneration Framework and Action Plan

Salford City Council Salford West Strategic Regeneration Framework and Action Plan Draft Report May 2007 Salford West Strategic Regeneration Framework and Action Plan Contents PART I: BASELINE AND EVIDENCE BASE 1 1. Background & Key Issues 2 Purpose of the Strategic Regeneration Framework 2 and Action Plan Methodology 3 Portrait of Salford West 4 2. Policy Context 9 Key Regional Policies 9 Key City Region Policies 10 Key City Wide Policies 11 Key Local Policies 15 Conclusions 16 3. Key Facts 18 A Successful Local Economy and Business 18 Location of Choice A Network of High Quality Neighbourhoods 20 An Outstanding Environment, Leisure and 21 Recreational Asset Connectivity 22 Inclusivity 23 4. Key Issues 25 A Successful Local Economy and Business 25 Location of Choice A Network of High Quality Neighbourhoods 25 An Outstanding Environment, Leisure and 26 Recreational Asset Salford West Strategic Regeneration Framework and Action Plan Connectivity 27 Inclusivity 27 5. Key Opportunities 29 A Successful Local Economy and Business 29 Location of Choice A Network of High Quality Neighbourhoods 30 An Outstanding Environment, Leisure and 30 Recreational Asset Connectivity 31 Inclusivity 31 6. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and 32 Challenges PART II: VISION AND INTERVENTION STRATEGY 34 7. Vision and Intervention Strategy 35 Introduction 35 Vision 36 Intervention Strategy 36 ‘Drivers’ of Change 38 ‘Enablers’ of Change 43 Spatial Priorities 46 Conclusions 46 PART III: ACTION PLAN 47 8. Action Plan 48 Introduction 48 Salford West Strategic Regeneration Framework and Action Plan Structure of the Action Plan 48 Preparation of the Action Plan 48 Description of Projects Within the Action Plan 48 Detailed Action Plan 64 9. -

'Pea~ Cvistrict Tjv!Iries CJ/Istorical Csociety-C"Ltd

'Pea~ CVistrict tJv!iries CJ/istorical CSociety-C"Ltd. NEWSLETTER Ro 67 JULY 1993 MAGPIE ENGINE HOUSE APPEAL By the time that you get this Newsletter you will have received, and digested, the Magpie Mine Engine Appeal brochure and other documentation. You will now know the details of the problems with the Engine House and how we intend to resolve them. One of the methods that we will use to raise the monies required is to hold special Magpie Mine Engine House Events. The first event of the appeal programme is a sponsored walk and a members car Boot and Swap event. Both of these events will be based on Magpie Mine and will take place on September 12th 1993. The walk will be about 12 miles long with plenty of opportunity to take a short cut back to the start if you so desire. The Car Boot and Swop event will give you the opportunity to dispose of your unwanted items, to be replaced immediately by other goods. Please give both of these events your full support. Go out and get the sponsors for the walk and then come along and en)oy yourself in a pleasant walk in the White Peak. The Society needs all of the support it can muster if the Engine House is to remain the focal point at Magpie Mine for many years to come. Full details of these appeal events are given in the programme of Society Meets on Page 3 of this Newsletter. CRICH MIKING DISPLAY The situation at the Crich Mining Display is now becoming critical. -

Agecroft Power Stations Generated Together the Original Boiler Plant Had Reached 30 Years for 10 Years

AGECROl?T POWER STATIONS 1924-1993 - About the author PETER HOOTON joined the electricity supply industry in 1950 at Agecroft A as a trainee. He stayed there until his retirement as maintenance service manager in 1991. Peter approached the brochure project in the same way that he approached work - with dedication and enthusiasm. The publication reflects his efforts. Acknowledgements MA1'/Y. members and ex members of staff have contributed to this history by providing technical information and their memories of past events In the long life of the station. Many of the tales provided much laughter but could not possibly be printed. To everyone who has provided informati.on and stories, my thanks. Thanks also to:. Tony Frankland, Salford Local History Library; Andrew Cross, Archivist; Alan Davies, Salford Mining Museum; Tony Glynn, journalist with Swinton & Pendlebury Journal; Bob Brooks, former station manager at Bold Power Station; Joan Jolly, secretary, Agecroft Power Station; Dick Coleman from WordPOWER; and - by no means least! - my wife Margaret for secretarial help and personal encouragement. Finally can I thank Mike Stanton for giving me lhe opportunity to spend many interesting hours talkin11 to coUcagues about a place that gave us years of employment. Peter Hooton 1 September 1993 References Brochure of the Official Opening of Agecroft Power Station, 25 September 1925; Salford Local History Library. Brochure for Agecroft B and C Stations, published by Central Electricity Generating Board; Salford Local Published by NationaJ Power, History Library. I September, 1993. Photographic albums of the construction of B and (' Edited and designed by WordPOWER, Stations; Salford Local Histo1y Libraty. -

Exploring Greater Manchester

Exploring Greater Manchester a fieldwork guide Web edition edited by Paul Hindle Original printed edition (1998) edited by Ann Gardiner, Paul Hindle, John McKendrick and Chris Perkins Exploring Greater Manchester 5 5. Urban floodplains and slopes: the human impact on the environment in the built-up area Ian Douglas University of Manchester [email protected] A. The River Mersey STOP 1: Millgate Lane, Didsbury The urban development of Manchester has modified From East Didsbury station and the junction of the A34 runoff to rivers (see Figure 1), producing changes in and A5145, proceed south along Parrs Wood Road and into flood behaviour, which have required expensive remedial Millgate Lane, Stop at the bridge over the floodbasin inlet measures, particularly, the embankment of the Mersey from channel at Grid Reference (GR) 844896 (a car can be turned Stockport to Ashton weir near Urmston. In this embanked round at the playing fields car park further on). Looking reach, runoff from the urban areas includes natural channels, south from here the inlet channel from the banks of the storm drains and overflows from combined sewers. Mersey can be seen. At flood times the gates of the weir on Alternative temporary storages for floodwaters involve the Mersey embankment can be opened to release water into release of waters to floodplain areas as in the Didsbury flood the Didsbury flood basin that lies to the north. Here, and at basin and flood storage of water in Sale and Chorlton water other sites along the Mersey, evidence of multi-purpose use parks. This excursion examines the reach of the Mersey from of the floodplain, for recreation and wildlife conservation as Didsbury to Urmston. -

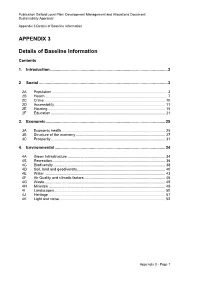

N SA Appendix 3 Details of Baseline Information

Publication Salford Local Plan: Development Management and Allocations Document Sustainability Appraisal Appendix 3 Details of Baseline Information APPENDIX 3 Details of Baseline Information Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................ 2 2 Social .................................................................................................................. 3 2A Population .............................................................................................................. 3 2B Health ..................................................................................................................... 7 2C Crime ................................................................................................................... 10 2D Accessibility .......................................................................................................... 11 2E Housing ................................................................................................................ 15 2F Education ............................................................................................................. 21 3. Economic .......................................................................................................... 25 3A Economic health ................................................................................................... 25 3B Structure of the economy .................................................................................... -

Walk 3 in Between

The Salford Trail is a new, long distance walk of about 50 public transport miles/80 kilometres and entirely within the boundaries The new way to find direct bus services to where you of the City of Salford. The route is varied, going through want to go is the Route Explorer. rural areas and green spaces, with a little road walking walk 3 in between. Starting from the cityscape of Salford Quays, tfgm.com/route-explorer the Trail passes beside rivers and canals, through country Access it wherever you are. parks, fields, woods and moss lands. It uses footpaths, tracks and disused railway lines known as ‘loop lines’. Start of walk The Trail circles around to pass through Kersal, Agecroft, Bus Number 92, 93, 95 Walkden, Boothstown and Worsley before heading off to Bus stop location Littleton Road Post Office Chat Moss. The Trail returns to Salford Quays from the historic Barton swing bridge and aqueduct. During the walk Bus Number 484 Blackleach Country Park Bus stop location Agecroft Road 5 3 Clifton Country Park End of walk 4 Walkden Roe Green Bus Number 8, 22 5 miles/8 km, about 2.5 hours Kersal Bus stop location Manchester Road, St Annes’s church 2 Vale 6 Worsley 7 Eccles Chat 1 more information Moss 8 Barton For information on any changes in the route please Swing Salford 9 Bridge Quays go to visitsalford.info/thesalfordtrail kersal to clifton Little Woolden 10 For background on the local history that you will This walk follows the River Irwell upstream Moss as it meanders through woodland and Irlam come across on the trail or for information on wildlife please go to thesalfordtrail.btck.co.uk open spaces to a large country park. -

Researching the Archaeology and History of the First Industrial Canal Nevell, MD and Wyke, T

Bridgewater 250: Researching the archaeology and history of the first industrial canal Nevell, MD and Wyke, T Title Bridgewater 250: Researching the archaeology and history of the first industrial canal Authors Nevell, MD and Wyke, T Type Book Section URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/22594/ Published Date 2012 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Bridgewater 250 Bridgewater Chapter 1 Bridgewater 250: Researching the Archaeology and History of the First Industrial Canal Michael Nevell & Terry Wyke “But so unbounded have the speculations in canals been, that neither hills nor dales, rocks nor mountains, could stop their progress, and whether the country afforded water to supply them, or mines and minerals to feed them with tonnage, or whether it was populous or otherwise, all amounted to nothing, for in the end, they were all Bridgewater Canals. His Grace’s canal had operated on the minds of canal speculators, much in the same manner as a large lottery prize does upon the minds of the inhabitants of a town, which has had the misfortune to be visited with such a calamity.” John Sutcliffe, A Treatise on Canals and Reservoirs. -

IL Combo Ndx V2

file IL COMBO v2 for PDF.doc updated 13-12-2006 THE INDUSTRIAL LOCOMOTIVE The Quarterly Journal of THE INDUSTRIAL LOCOMOTIVE SOCIETY COMBINED INDEX of Volumes 1 to 7 1976 – 1996 IL No.1 to No.79 PROVISIONAL EDITION www.industrial-loco.org.uk IL COMBO v2 for PDF.doc updated 13-12-2006 INTRODUCTION and ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This “Combo Index” has been assembled by combining the contents of the separate indexes originally created, for each individual volume, over a period of almost 30 years by a number of different people each using different approaches and methods. The first three volume indexes were produced on typewriters, though subsequent issues were produced by computers, and happily digital files had been preserved for these apart from one section of one index. It has therefore been necessary to create digital versions of 3 original indexes using “Optical Character Recognition” (OCR), which has not proved easy due to the relatively poor print, and extremely small text (font) size, of some of the indexes in particular. Thus the OCR results have required extensive proof-reading. Very fortunately, a team of volunteers to assist in the project was recruited from the membership of the Society, and grateful thanks are undoubtedly due to the major players in this exercise – Paul Burkhalter, John Hill, John Hutchings, Frank Jux, John Maddox and Robin Simmonds – with a special thankyou to Russell Wear, current Editor of "IL" and Chairman of the Society, who has both helped and given encouragement to the project in a myraid of different ways. None of this would have been possible but for the efforts of those who compiled the original individual indexes – Frank Jux, Ian Lloyd, (the late) James Lowe, John Scotford, and John Wood – and to the volume index print preparers such as Roger Hateley, who set a new level of presentation which is standing the test of time. -

Croal/Irwell Local Environment Agency Plan Environmental Overview October 1998

Croal/Irwell Local Environment Agency Plan Environmental Overview October 1998 NW - 10/98-250-C-BDBS E n v ir o n m e n t Ag e n c y Croal/lrwell 32 Local Environment Agency Plan Map 1 30 30 E n v ir o n m e n t Ag e n c y Contents Croal/lrwell Local Environment Agency Plan (LEAP) Environmental Overview Contents 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Air Quality 2 1.3 Water Quality 7 1.4 Effluent Disposal 12 1.5 Hydrology. 15 1.6 Hydrogeology 17 1.7 Water Abstraction - Surface and Groundwater 18 1.8 Area Drainage 20 1.9 Waste Management 29 1.10 Fisheries 36 1.11 . Ecology 38 1.12 Recreation and Amenity 45 1.13 Landscape and Heritage 48 1.14 Development . 5 0 1.15 Radioactive Substances 56 / 1.16 Agriculture 57 Appendix 1 - Glossary 60 Appendix 2 - Abbreviations ' 66 Appendix 3 - River Quality Objectives (RQOs) 68 Appendix 4 - Environment Agency Leaflets and Reports 71 Croal/lrwell LEAP l Environmental Overview Maps Number Title Adjacent to Page: 1 The Area Cover 2 Integrated Pollution Control (IPC) 3 3 Water Quality: General Quality Assessment Chemical Grading 1996 7 4 Water Quality: General Quality Assessment: Biological Grading 1995 8 5 Water Quality: Compliance with proposed Short Term River Ecosystem RQOs 9 6 Water Quality: Compliance with proposed Long Term River Ecosystem RQOs 10 7 EC Directive Compliance 11 8 Effluent Disposal 12 9 Rainfall 15 10 Hydrometric Network 16 11 Summary Geological Map: Geology at Surface (simplified) 17 12 Licensed Abstractions>0.5 Megalitre per day 18 13 Flood Defence: River Network 21 14 Flood Defence: River Corridor -

Lancashire Countryside Directory for People with Disabilities

Lancashire Countryside Directory for People with Disabilities Second edition Whatever your needs, access to and enjoyment of the countryside is rewarding, healthy and great fun. This directory can help you find out what opportunities are available to you in your area. Get yourself outdoors and enjoy all the benefits that come with it… Foreword written by: Bill Oddie OBE This directory was designed for people with a disability, though the information included will be useful to everyone. Lancashire’s countryside has much to offer; from the gritstone fells of the Forest of Bowland to the sand dunes of the Sefton Coast. There are some great opportunities to view wildlife too, including red squirrels and marsh harriers. It is more than worth taking that first step and getting yourself involved in your local countryside, regardless of your abilities. For people interested in wildlife and conservation there is much that can be done from home or a local accessible area. Whatever your chosen form of countryside recreation, whether it’s joining a group, doing voluntary work, or getting yourself out into the countryside on your own, we hope you will get as much out of it as we do. There is still some way to go before we have a properly accessible countryside. By contacting Open Country or another of the organisations listed here, you can help us to encourage better access for all in the future. This Second Edition published Summer 2019 Copyright © Open Country 2019 There are some things that some disabilities make “ more difficult. The countryside and wildlife should not be among them.