The Language of Humor: Navajo Ruth E. Cisneros, Joey Alexanian, Jalon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Sign Language and the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Presidential Scholars Theses (1990 – 2006) Honors Program 2005 Using space to describe space: American Sign Language and the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis Cindee Calton University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2005 - Cindee Calton Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pst Part of the American Sign Language Commons Recommended Citation Calton, Cindee, "Using space to describe space: American Sign Language and the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis" (2005). Presidential Scholars Theses (1990 – 2006). 56. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pst/56 This Open Access Presidential Scholars Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Presidential Scholars Theses (1990 – 2006) by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Using Space to Describe Space: American Sign Language and the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Cindee Calton University of Northern Iowa Undergraduate Research April 2005 Faculty Advisor, Dr. Cynthia Dunn - - - -- - Abstract My study sought to combine two topics that have recently generated much interest among anthropologists. One of these topics is American Sign Language, the other is linguistic relativity. Although both topics have been a part of the literature for some time, neither has been studied extensively until the recent past. Both present exciting new horizons for understanding culture, particularly language and culture. The first of these two topics is the study of American Sign Language. The reason for its previous absence from the literature has to do with unfortunate prejudice which, for a long time, kept ASL from being recognized as a legitimate language. -

Chapter 1 Navajo and the Athabaskan Languages

Chapter 1 Navajo and the Athabaskan Languages The Navajo language belongs to the Athabaskan/Dene language group. The Athabaskan language family stretches across Alaska and northwest Canada, with branches on the coast of California, Oregon, and Washington, and in the Southwest of the United States. Most Navajo people live in the southwestern parts of the United States in Arizona, New Mexico and Utah. The Apaches in Arizona and New Mexico also belong to the Southern Athabaskans. The Navajo population today is approximately 300,000. The Navajo Nation covers approximately 25,500 square miles, about the size of West Virginia. 1. The Status of Navajo In 1951, Reichard recorded that Navajo was spoken by some 60,000 persons two-thirds of whom do not and perhaps never will speak English. We are at point where the opposite is true or worse. Estimates about the current number of speakers vary substantially, from 80,000 to 150,000 speakers. The Navajo language has a larger speech community than any other indigenous language in the United States, yet the language is in far greater danger than most linguists realize. Most Navajo men and women over the age of 50 speak Navajo fluently. Navajos in their thirties and forties have varying degrees of fluency. Some can understand the language fairly well but are not able to produce it accurately. There are fluent speakers who are in their twenties, but more know only a few common phrases. The vast majority of Navajos under age 20 speak only English. This decline has been well documented. Platero (2000) documents a sharp decline in the percentage of Navajo pre-school age children who speak Navajo, from 80% in his 1974 study, to about 45% in 1992. -

Article Title

Dennis L. Malone and Isara Choosri Stabilizing Indigenous Languages 1 Symposium Report Stabilizing Indigenous Languages Dennis L. Malone and Isara Choosri* A note from Pat Kelley, SIL International Literacy Coordinator Few of our field practitioners are strategically located for attending some of the conferences around the world that may be related to the work we do in literacy. Also, in many cases, especially if no paper is being presented, there may be limited funds available for transportation. Yet there is much to be learned from such conferences: for example, vocabulary and new terminology, current trends, what’s “out there” in the prominent theory and practice of related fields applicable to our work, current research, issues defined by the “voices” for literacy, etc. For that reason, when our SIL literacy personnel and national colleagues do attend or present at a conference, on occasion we’ll include a “Conference Report” … so that our field personnel may glean information from them. When possible, contact details will be provided in order to request additional information. These reports will reflect the growing trend in the Literacy domain for copresenting and coauthoring, which hopefully will continue as we determine to see capacity building in this area among our national colleagues. Dennis Malone (SIL International in Bangkok, Thailand), and Isara Choosri (Institute of Language and Culture for Rural Development at Mahidol University at Salaya, Thailand) coauthor this report of the Ninth Annual Symposium on Stabilizing Indigenous • Dennis Malone ([email protected]) is an International Literacy Consultant, serving with his wife Susan in the Asia Area. He is involved in minority language education projects in the Asia Area and also serves as a guest lecturer at the ILCRD. -

MIXED CODES, BILINGUALISM, and LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requi

BILINGUAL NAVAJO: MIXED CODES, BILINGUALISM, AND LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Charlotte C. Schaengold, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Brian Joseph, Advisor Professor Donald Winford ________________________ Professor Keith Johnson Advisor Linguistics Graduate Program ABSTRACT Many American Indian Languages today are spoken by fewer than one hundred people, yet Navajo is still spoken by over 100,000 people and has maintained regional as well as formal and informal dialects. However, the language is changing. While the Navajo population is gradually shifting from Navajo toward English, the “tip” in the shift has not yet occurred, and enormous efforts are being made in Navajoland to slow the language’s decline. One symptom in this process of shift is the fact that many young people on the Reservation now speak a non-standard variety of Navajo called “Bilingual Navajo.” This non-standard variety of Navajo is the linguistic result of the contact between speakers of English and speakers of Navajo. Similar to Michif, as described by Bakker and Papen (1988, 1994, 1997) and Media Lengua, as described by Muysken (1994, 1997, 2000), Bilingual Navajo has the structure of an American Indian language with parts of its lexicon from a European language. “Bilingual mixed languages” are defined by Winford (2003) as languages created in a bilingual speech community with the grammar of one language and the lexicon of another. My intention is to place Bilingual Navajo into the historical and theoretical framework of the bilingual mixed language, and to explain how ii this language can be used in the Navajo speech community to help maintain the Navajo language. -

8. Classifiers

158 II. Morphology 8. Classifiers 1. Introduction 2. Classifiers and classifier categories 3. Classifier verbs 4. Classifiers in signs other than classifier verbs 5. The acquisition of classifiers in sign languages 6. Classifiers in spoken and sign languages: a comparison 7. Conclusion 8. Literature Abstract Classifiers (currently also called ‘depicting handshapes’), are observed in almost all sign languages studied to date and form a well-researched topic in sign language linguistics. Yet, these elements are still subject to much debate with respect to a variety of matters. Several different categories of classifiers have been posited on the basis of their semantics and the linguistic context in which they occur. The function(s) of classifiers are not fully clear yet. Similarly, there are differing opinions regarding their structure and the structure of the signs in which they appear. Partly as a result of comparison to classifiers in spoken languages, the term ‘classifier’ itself is under debate. In contrast to these disagreements, most studies on the acquisition of classifier constructions seem to consent that these are difficult to master for Deaf children. This article presents and discusses all these issues from the viewpoint that classifiers are linguistic elements. 1. Introduction This chapter is about classifiers in sign languages and the structures in which they occur. Classifiers are reported to occur in almost all sign languages researched to date (a notable exception is Adamorobe Sign Language (AdaSL) as reported by Nyst (2007)). Classifiers are generally considered to be morphemes with a non-specific meaning, which are expressed by particular configurations of the manual articulator (or: hands) and which represent entities by denoting salient characteristics. -

The Case of Navajo

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 6. Editor: Peter K. Austin Language management for endangered languages: the case of Navajo BERNARD SPOLSKY Cite this article: Bernard Spolsky (2009). Language management for endangered languages: the case of Navajo. In Peter K. Austin (ed.) Language Documentation and Description, vol 6. London: SOAS. pp. 117-131 Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/073 This electronic version first published: July 2014 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Terms of use: http://www.elpublishing.org/terms Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions Language management for endangered languages: the case of Navajo Bernard Spolsky 1. Introduction In this paper I outline an approach to building a theory of language management and its application to endangered languages. As I see it, language management is one of the three interconnected components of language policy (see Sallabank, this volume): the other two are language practices and language beliefs. To clarify how this works, I will illustrate the model with the case of Navajo, which is the second largest Native American tribe (after Cherokee) in the United States but whose language is not unreasonably considered to be endangered (Lee and McLaughlin 2001). -

Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools

Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools Resource Directory Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools Resource Directory: Table of Contents and Section Descriptions 1. Linguistic Resources Academic linguistics articles, reference materials, and online language resources for each BC First Nations language. 2. Language-Specific Resources Practical teaching resources and curriculum identified for each BC First Nations language. 3. Adaptable Resources General curriculum and teaching resources which can be adapted for teaching BC First Nations languages: books, curriculum documents, online and multimedia resources. Includes copies of many documents in PDF format. 4. Language Revitalization Resources This section includes general resources on language revitalization, as well as resources on awakening languages, teaching methods for language revitalization, materials and activities for language teaching, assessing the state of a language, envisioning and planning a language program, teacher training, curriculum design, language acquisition, and the role of technology in language revitalization. 5. Language Teaching Journals A list of journals relevant to teachers of BC First Nations languages. 6. Further Education This section highlights opportunities for further education, training, certification, and professional development. It includes a list of conferences and workshops relevant to BC First Nations language teachers, and a spreadsheet of post‐ secondary programs relevant to Aboriginal Education and Teacher Training - in BC, across Canada, in the USA, and around the world. 7. Funding This section includes a list of funding sources for Indigenous language revitalization programs, as well as a list of scholarships and bursaries available for Aboriginal students and students in the field of Education, in BC, across Canada, and at specific institutions. -

Elizabeth Bogal-Allbritten, "Domains and Interaction of Plurality in Navajo"

Domains and Interaction of Plurality in Navajo Elizabeth Bogal-Allbritten LING 720 December 9, 2010 Roadmap: §1: Pluractionality as pluralization of event arguments (Lasersohn 1995) §2: Crash course in Navajo (Athabaskan); loci of verbal plurality marking • Number-marking verb stems §3: Hi- seriative prefix: time as a parameter §4: Conclusions • Future puzzle: Da- plural number prefix: pluralizer of events or entities? 1.0 Introduction (1) V-PA(E) ⇔ ∀e,e’ ∈ E [P(e) ∧ ¬ f(e) f(e’)] ∧ |(E)| > n a b c d (adapt. Lasersohn 1995: 256) a: Pluractionality markers (PA) encode existence of multiple events (sum: E), not the plurality of the verb’s arguments. The cardinality of this plural event exceeds n, which is determined contextually or on a language-by-language basis (Lasersohn 1995: 241). b: P is a variable ranging over properties of events. P is used instead of V because pluractional markers can encode both repeated and repetitive action. o Repeated action: “multiple events of the type denoted by the verb” . P = V o Repetitive action: “multiple [subevents] of a different type, but which sum up to form a single token of the event type corresponding to the verb.” (Lasersohn 1995: 244) . P is fixed lexically. The availability of a repetitive reading of the pluractional marker is a line along with languages can vary. c: Events e, e’ within X do not overlap (). Events are distinguished by a parameter f. o Events can be distributed to “different times, locations, or participants” (Lasersohn 1995: 251). 1 • Given the different settings theoretically available to the pluractional marker – both cross-linguistically and within a single language – it is not surprise that pluractional morphology gives rise to a large number of interpretations, across languages and within languages. -

Becoming “Fully” Hopi: the Role of the Hopi Language in the Contemporary Lives of Hopi Youth

Becoming "Fully" Hopi: The Role of Hopi Language in the Contemporary Lives Of Hopi Youth-- A Hopi Case Study of Language Shift and Vitality Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Nicholas, Sheilah Ernestine Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 11/10/2021 04:07:30 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194190 BECOMING “FULLY” HOPI: THE ROLE OF THE HOPI LANGUAGE IN THE CONTEMPORARY LIVES OF HOPI YOUTH – A HOPI CASE STUDY OF LANGUAGE SHIFT AND VITALITY by Sheilah E. Nicholas ______________________ Copyright© Sheilah E. Nicholas 2008 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE INTERDISCIPLINARY PROGRAM IN AMERICAN INDIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 8 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Sheilah E. Nicholas entitled Becoming “Fully” Hopi: The Role of the Hopi Language in the Contemporary Lives of Hopi Youth—A Case Study of Hopi Language Shift and Vitality and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dr. Tsianina Lomawaima Date: May 8, 2007 Dr. Teresa McCarty _________________________________________ Date: May 8, 2007 Emory Sekaquaptewa Date: May 8, 2007 Dr. -

Revitalizing Indigenous Languages

Revitalizing Indigenous Languages edited by Jon Reyhner Gina Cantoni Robert N. St. Clair Evangeline Parsons Yazzie Flagstaff, Arizona 1999 Revitalizing Indigenous Languages is a compilation of papers presented at the Fifth Annual Stabilizing Indigenous Languages Symposium on May 15 and 16, 1998, at the Galt House East in Louisville, Kentucky. Symposium Advisory Board Robert N. St. Clair, Co-chair Evangeline Parsons Yazzie, Co-chair Gina Cantoni Barbara Burnaby Jon Reyhner Symposium Staff Tyra R. Beasley Sarah Becker Yesenia Blackwood Trish Burns Emil Dobrescu Peter Matallana Rosemarie Maum Jack Ramey Tina Rose Mike Sorendo Nancy Stone B. Joanne Webb Copyright © 1999 by Northern Arizona University ISBN 0-9670554-0-7 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 99-70356 Second Printing, 2005 Additional copies can be obtained from College of Education, Northern Ari- zona University, Box 5774, Flagstaff, Arizona, 86011-5774. Phone 520 523 5342. Reprinting and copying on a nonprofit basis is hereby allowed with proper identification of the source except for Richard Littlebear’s poem on page iv, which can only be reproduced with his permission. Publication information can be found at http://jan.ucc.nau.edu/~jar/TIL.html ii Contents Repatriated Bones, Unrepatriated Spirits iv Richard Littlebear Introduction: Some Basics of Language Revitalization v Jon Reyhner Obstacles and Opportunities for Language Revitalization 1. Some Rare and Radical Ideas for Keeping Indigenous Languages Alive 1 Richard Littlebear 2. Running the Gauntlet of an Indigenous Language Program 6 Steve Greymorning Language Revitalization Efforts and Approaches 3. Sm’algyax Language Renewal: Prospects and Options 17 Daniel S. Rubin 4. Reversing Language Shift: Can Kwak’wala Be Revived 33 Stan J. -

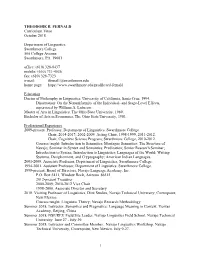

THEODORE B. FERNALD Curriculum Vitae October 2018

THEODORE B. FERNALD Curriculum Vitae October 2018 Department of Linguistics Swarthmore College 500 College Avenue Swarthmore, PA 19081 office: (610) 328-8437 mobile: (610) 731-4536 fax: (610) 328-7323 e-mail: [email protected] home page: https://www.swarthmore.edu/profile/ted-fernald Education Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics, University of California, Santa Cruz, 1994. Dissertation: On the Nonuniformity of the Individual- and Stage-Level Effects, supervised by William A. Ladusaw. Master of Arts in Linguistics, The Ohio State University, 1989. Bachelor of Arts in Economics, The Ohio State University, 1981. Professional Experience 2009-present. Professor, Department of Linguistics, Swarthmore College. Chair, 2014-2017; 2002-2009. Acting Chair, 1998-1999, 2011-2012. Chair, Cognitive Science Program, Swarthmore College, 2010-2012. Courses taught: Introduction to Semantics; Montague Semantics; The Structure of Navajo; Seminar in Syntax and Semantics: Predication; Senior Research Seminar; Introduction to Syntax; Introduction to Linguistics; Languages of the World; Writing Systems, Decipherment, and Cryptography; American Indian Languages. 2001-2009. Associate Professor, Department of Linguistics, Swarthmore College. 1994-2001. Assistant Professor, Department of Linguistics, Swarthmore College. 1998-present. Board of Directors, Navajo Language Academy, Inc. P.O. Box 5411, Window Rock, Arizona 86515 2012-present Treasurer 2000-2009; 2010-2012 Vice Chair 1998-2000. Associate Director and Secretary 2018. Visiting Professor of Linguistics, Diné Studies, Navajo Technical University, Crownpoint, New Mexico. Courses taught: Linguistic Theory; Navajo Research Methodology Summer 2018. Instructor. Semantics and Pragmatics: Language Meaning in Context. Veritas Academy, Beijing, China. Summer 2018. NSF/REU Field Site Leader. Navajo Linguistics Field School. Navajo Technical University. June 27 - July 29. -

Navajo Language Renaissance Announces Launch of the Rosetta Stone Navajo Mobile App

Navajo Language Renaissance Announces Launch of the Rosetta Stone Navajo Mobile App November 9, 2020 Arlington, VA, Nov. 09, 2020 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Rosetta Stone Inc., a division of Cambium Learning Group, Inc., and Navajo Language Renaissance announced today the release of the mobile app for the popular Navajo language-learning software in use by Navajo in language revitalization. Though Navajo is the most-spoken Native American language north of Mexico (still spoken by more than 100,000 people), its use and fluency among younger generations is in dramatic decline. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, only 50 percent of Navajo ages 17 and under were able to speak their native language at all in 2000. The Rosetta Stone Navajo mobile app for iPhone, iPad and Android will be available for use in Navajo Nation schools, homes and chapter houses in an effort to help reverse this decline. The Rosetta Stone Navajo mobile app will be sold through Navajo Language Renaissance, a nonprofit group of Navajo educators from the tri-state area of Arizona, New Mexico and Utah. The original CD and online version of the software was released in 2010, with the endorsements of the Department of Diné Education and the Navajo Board of Education. More than one hundred Navajo contributed to the project by providing language expertise, photos, audio recordings and logistical and cultural support. All proceeds from the sale of the software go toward future initiatives to revitalize the Navajo language. Rosetta Stone has developed software for several indigenous languages, including Chitimacha, Iñupiaq, Mohawk, Inuttitut, and Chickasaw.