Ed. Jane Grogan (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2010), Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

18_121726-bindex.qxp 4/17/09 2:59 PM Page 486 Index See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX Ardnagashel Estate, 171 Bank of Ireland The Ards Peninsula, 420 Dublin, 48–49 Abbey (Dublin), 74 Arigna Mining Experience, Galway, 271 Abbeyfield Equestrian and 305–306 Bantry, 227–229 Outdoor Activity Centre Armagh City, 391–394 Bantry House and Garden, 229 (Kildare), 106 Armagh Observatory, 394 Barna Golf Club, 272 Accommodations. See also Armagh Planetarium, 394 Barracka Books & CAZ Worker’s Accommodations Index Armagh’s Public Library, 391 Co-op (Cork City), 209–210 saving money on, 472–476 Ar mBréacha-The House of Beach Bar (Aughris), 333 Achill Archaeological Field Storytelling (Wexford), Beaghmore Stone Circles, 446 School, 323 128–129 The Beara Peninsula, 230–231 Achill Island, 320, 321–323 The arts, 8–9 Beara Way, 230 Adare, 255–256 Ashdoonan Falls, 351 Beech Hedge Maze, 94 Adrigole Arts, 231 Ashford Castle (Cong), 312–313 Belfast, 359–395 Aer Lingus, 15 Ashford House, 97 accommodations, 362–368 Agadhoe, 185 A Store is Born (Dublin), 72 active pursuits, 384 Aillwee Cave, 248 Athlone, 293–299 brief description of, 4 Aircoach, 16 Athlone Castle, 296 gay and lesbian scene, 390 Airfield Trust (Dublin), 62 Athy, 102–104 getting around, 362 Air travel, 461–468 Athy Heritage Centre, 104 history of, 360–361 Albert Memorial Clock Tower Atlantic Coast Holiday Homes layout of, 361 (Belfast), 377 (Westport), 314 nightlife, 386–390 Allihies, 230 Aughnanure Castle (near the other side of, 381–384 All That Glitters (Thomastown), -

Hydrogeology of the Burren and Gort Lowlands

KARST HYDROGEOLOGY OF THE BURREN UPLANDS / GORT LOWLANDS Field Guide International Association of Hydrogeologists (IAH) Irish Group 2019 Cover page: View north across Corkscrew Hill, between Lisdoonvarna and Ballyvaughan, one of the iconic Burren vistas. Contributors and Excursion Leaders. Colin Bunce Burren and Cliffs of Moher UNESCO Global Geopark David Drew Department of Geography, Trinity College, Dublin Léa Duran Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, Trinity College, Dublin Laurence Gill Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, Trinity College, Dublin Bruce Misstear Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, Trinity College, Dublin John Paul Moore Fault Analysis Group, Department of Geology, University College Dublin and iCRAG Patrick Morrissey Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, Trinity College, Dublin and Roughan O‘Donovan Consulting Engineers David O’Connell Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, Trinity College, Dublin Philip Schuler Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, Trinity College, Dublin Luka Vucinic Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, Trinity College, Dublin and iCRAG Programme th Saturday 19 October 10.00 Doolin Walk north of Doolin, taking in the coast, as well as the Aillwee, Balliny and Fahee North Members, wayboards, chert beds, heterogeneity in limestones, joints and veins, inception horizons, and epikarst David Drew and Colin Bunce, with input from John Paul Moore 13.00 Lunch in McDermotts Bar, Doolin 14.20 Murrooghtoohy Veins and calcite, relationship to caves, groundwater flow and topography John Paul Moore 15.45 Gleninsheen and Poll Insheen Holy Wells, epikarst and hydrochemistry at Poll Insheen Bruce Misstear 17.00 Lisdoonvarna Spa Wells Lisdoonvarna history, the spa wells themselves, well geology, hydrogeology and hydrochemistry, some mysterious heat .. -

Carnaval Do Galway the Brazilian Community in Gort, 1999-2006

Irish Migration Studies in Latin America Vol. 4, No. 3: July 2006 www.irlandeses.org Carnaval do Galway The Brazilian Community in Gort, 1999-2006 By Claire Healy Gort Inse Guaire, or Gort, lies just north of the border with County Clare in south County Galway in the West of Ireland, and has a population of about three thousand people. It is situated between the Slieve Aughty mountains and the unique karstic limestone landscape of the Burren, in the heartland of the countryside made famous by Lady Augusta Gregory and the poet W.B. Yeats in nearby Coole Park and Thoor Ballylee. Nineteenth- century Gort was a thriving market town providing a commercial centre for its fertile agricultural hinterland. A Sabor Brasil shop on Georges St., Gort market was held in the market (Claire Healy 2006) square every Saturday, and sheep, cattle and pig fairs were held regularly. A cavalry barracks accommodating eight British officers and eighty-eight soldiers was situated near the town and the Dublin and Limerick mail coaches trundled along the main street. [1] Throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, day labourers congregated on the market square in the centre of town hoping for a day’s seasonal work on a farm. By the 1990s, the town had become a quiet and sparsely populated shadow of its former self. Many of the shops along the main street, Georges Street, were shutting their doors for the last time, and the town was familiar to most Irish people only as a brief stop on the bus route from Galway to the southern cities of Cork and Limerick. -

A Sunny Day in Sligo

June 2009 VOL. 20 #6 $1.50 Boston’s hometown journal of Irish culture. Worldwide at bostonirish.com All contents copyright © 2009 Boston Neighborhood News, Inc. Picture of Grace: A Sunny Day in Sligo The beauty of the Irish landscape, in this case, Glencar Lough in Sligo at the Leitrim border, jumps off the page in this photograph by Carsten Krieger, an image taken from her new book, “The West of Ireland.” Photo courtesy Man-made Images, Donegal. In Charge at the BPL Madame President and Mr. Mayor Amy Ryan is the multi- tasking president of the venerable Boston Pub- lic Library — the first woman president in the institution’s 151-year his- tory — and she has set a course for the library to serve the educational and cultural needs of Boston and provide access to some of the world’s most historic records, all in an economy of dramatic budget cuts and a significant rise in library use. Greg O’Brien profile, Page 6 Nine Miles of Irishness On Old Cape Cod, the nine-mile stretch along Route 28 from Hyannis to Harwich is fast becom- ing more like Galway or Kerry than the Cape of legend from years ago. This high-traffic run of roadway is dominated by Irish flags, Irish pubs, Irish restaurants, Irish hotels, and one of the fast- est-growing private Irish Ireland President Mary McAleese visited Boston last month and was welcomed to the city by Boston clubs in America. Mayor Tom Menino. Also pictured at the May 26 Parkman House event were the president’s husband, BIR columnist Joe Dr. -

The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather

Finding a Voice: The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather Macdougall A Thesis in the PhD Humanities Program Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2012 © Heather Macdougall, 2012 ABSTRACT Finding a Voice: The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather Macdougall, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2012 This dissertation investigates the history of film production in the minority language of Irish Gaelic. The objective is to determine what this history reveals about the changing roles of both the national language and national cinema in Ireland. The study of Irish- language film provides an illustrative and significant example of the participation of a minority perspective within a small national cinema. It is also illustrates the potential role of cinema in language maintenance and revitalization. Research is focused on policies and practices of filmmaking, with additional consideration given to film distribution, exhibition, and reception. Furthermore, films are analysed based on the strategies used by filmmakers to integrate the traditional Irish language with the modern medium of film, as well as their motivations for doing so. Research methods included archival work, textual analysis, personal interviews, and review of scholarly, popular, and trade publications. Case studies are offered on three movements in Irish-language film. First, the Irish- language organization Gael Linn produced documentaries in the 1950s and 1960s that promoted a strongly nationalist version of Irish history while also exacerbating the view of Irish as a “private discourse” of nationalism. Second, independent filmmaker Bob Quinn operated in the Irish-speaking area of Connemara in the 1970s; his fiction films from that era situated the regional affiliations of the language within the national context. -

The Historical Development of Irish Euroscepticism to 2001

The Historical Development of Irish Euroscepticism to 2001 Troy James Piechnick Thesis submitted as part of the Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) program at Flinders University on the 1st of September 2016 Social and Behavioural Sciences School of History and International Relations Flinders University 2016 Supervisors Professor Peter Monteath (PhD) Dr Evan Smith (PhD) Associate Professor Matt Fitzpatrick (PhD) Contents GLOSSARY III ABSTRACT IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS V CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1 DEFINITIONS 2 PARAMETERS 13 LITERATURE REVIEW 14 MORE RECENT DEVELOPMENTS 20 THESIS AND METHODOLOGY 24 STRUCTURE 28 CHAPTER 2 EARLY ANTECEDENTS OF IRISH EUROSCEPTICISM: 1886–1949 30 IRISH REPUBLICANISM, 1780–1886 34 FIRST HOME RULE BILL (1886) AND SECOND HOME RULE BILL (1893) 36 THE BOER WAR, 1899–1902 39 SINN FÉIN 40 WORLD WAR I AND EASTER RISING 42 IRISH DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 46 IRISH WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1919 AND CIVIL WAR 1921 47 BALFOUR DECLARATION OF 1926 AND THE STATUTE OF WESTMINSTER IN 1931 52 EAMON DE VALERA AND WORLD WAR II 54 REPUBLIC OF IRELAND ACT 1948 AND OTHER IMPLICATIONS 61 CONCLUSION 62 CHAPTER 3 THE TREATY OF ROME AND FAILED APPLICATIONS FOR MEMBERSHIP IN 1961 AND 1967 64 THE TREATY OF ROME 67 IRELAND IN THE 1950S 67 DEVELOPING IRISH EUROSCEPTICISM IN THE 1950S 68 FAILED APPLICATIONS FOR MEMBERSHIP IN 1961 AND 1967 71 IDEOLOGICAL MAKINGS: FURTHER DEVELOPMENTS OF A EUROSCEPTIC NATURE (1960S) 75 Communist forms of Irish euroscepticism 75 Irish eurosceptics and republicanism 78 Irish euroscepticism accommodating democratic socialism 85 -

Irish Political Review, January 2007

Workers' Control Douglas Gageby Frank Aiken Conor Lynch John Martin Pat Walsh page 26 page 6 page 14 IRISH POLITICAL REVIEW January 2007 Vol.22, No.12 ISSN 0790-7672 and Northern Star incorporating Workers' Weekly Vol.21 No.1 ISSN 954-5891 The Haughey Settlement ? Blackwash: As far as democracy is concerned, Northern Ireland is a No-man's-land between two Moriarty Presumes states. The two states threw it into chaos in 1969, and Provisional Republicanism emerged from the chaos. The two states have ever since had the object of tidying away After the great age of the Enlighten- the North, sealing it up, and forgetting about it until the next time. ment the Germans brought forth a mouse. It may be that they are about to succeed. The signs are that Sinn Fein is about to sign That was Friedrich Nietzsche's contempt- up for a pig-in-a-poke in the matter of policing; and that the DUP is about to accept as uous comment on Martin Luther and the democracy an arrangement which it understands very well not to be democracy. Protestant Reformation. And we hear that A subordinate layer of local government, conducted under the supervision of the state Dermot "the Kaiser" Desmond has said authority, with its power of decision crippled by peculiar arrangements designed to the same about the Moriarty Tribunal shackle the majority, is not something which would be recognised as democracy by the following the millions it has spent on political strata of the British or Irish states if applied to their own affairs. -

Pindar and Yeats: the Mythopoeic Vision

Colby Quarterly Volume 24 Issue 4 December Article 3 December 1988 Pindar and Yeats: The Mythopoeic Vision Ann L. Derrickson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 24, no.4, December 1988, p.176-186 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Derrickson: Pindar and Yeats: The Mythopoeic Vision Pindar and Yeats: The Mythopoeic Vision by ANN L. DERRICKSON ROM THE Greece of Pindar to the Ireland of Yeats, 2,300 years canle Fcoursing down the riverbed of history, washing over the widening delta of poetry, leaving layers of political context and literary convention. Yet a shape emerges, despite the shifts of eras and of nations, a form fun damental to the lyric. Thinking about the two poets together, then, helps produce an understanding of what is basic to and defines the genre oflyric poetry. Its nature is not specifically a matter of theme but a relationship of reference; action serves to describe spirit. As in Yeats's phrase from "The Circus Animals' Desertion," the prime concern is "Character isolated by a deed." Because it is on this plane of human spirit that meaning distills from the works of Pindar and Yeats, their writing shares the label "lyric." For both poets the vital creative tension exists between a given occasion and its associated images, rather than between concepts of present and past or fact and fantasy. -

"The Wild Beauty I Found There": Plath's Connemara Gail Crowther

208 "The wild beauty I found there": Plath's Connemara Gail Crowther The yellows and browns of Connemara are wild. Undulating hills and loughs and inlets where the Atlantic creams over black rocks and the sky and sea join, held together by flat white clouds. The pungent gorse bushes and the roadside fuschias and mallows and spikey hedgerows border peat bogs and marshy brown puddles of water. Megalithic tombs balance their stones atop slight mounds and small cottages huddle in sheltered cut out gardens against the mountains and the sea. Wild Connemara is where Sylvia Plath initially chose to escape in the upset of her final year. A brief visit to Cleggan to stay with the poet Richard Murphy in September 1962 was enough to captivate her. In Murphy's words: "She seemed to have fallen in love with Connemara at first sight" (Bitter Fame 350). This paper aims to explore Plath's time in Connemara, the places she visited and her plans to winter there from December 1962 until late February 1963. While I will not be discussing at any great length the details of her visit there (this has already been done by her host Richard Murphy elsewhere), I will be drawing on Plath's own impression of Connemara using both published and unpublished letters that she wrote to family and friends. 1 Since Plath's journals from this time are lost/missing, letters are the main first-hand sources of information from this period in Plath's life. Following Plath's trail on a recent visit to 1 See Appendix III in Bitter Fame (348-359) and Murphy's autobiography The Kick. -

![Études Irlandaises, 39-2 | 2014, « Les Religions En République D’Irlande Depuis 1990 » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 20 Novembre 2016, Consulté Le 02 Avril 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6370/%C3%A9tudes-irlandaises-39-2-2014-%C2%AB-les-religions-en-r%C3%A9publique-d-irlande-depuis-1990-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-20-novembre-2016-consult%C3%A9-le-02-avril-2020-1646370.webp)

Études Irlandaises, 39-2 | 2014, « Les Religions En République D’Irlande Depuis 1990 » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 20 Novembre 2016, Consulté Le 02 Avril 2020

Études irlandaises 39-2 | 2014 Les religions en République d’Irlande depuis 1990 Eamon Maher et Catherine Maignant (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/3867 DOI : 10.4000/etudesirlandaises.3867 ISSN : 2259-8863 Éditeur Presses universitaires de Caen Édition imprimée Date de publication : 20 novembre 2014 ISBN : 978-2-7535-3559-6 ISSN : 0183-973X Référence électronique Eamon Maher et Catherine Maignant (dir.), Études irlandaises, 39-2 | 2014, « Les religions en République d’Irlande depuis 1990 » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 20 novembre 2016, consulté le 02 avril 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/3867 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ etudesirlandaises.3867 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 2 avril 2020. Études irlandaises est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d’Utilisation Commerciale - Partage dans les Mêmes Conditions 4.0 International. 1 SOMMAIRE Avant-propos Eamon Maher et Catherine Maignant Introduction : les données Le paysage religieux de la République et de l’Irlande du Nord au début du XXIe siècle Catherine Piola L’église catholique en question : évolutions et enjeux The Aggiornamento of the Irish Catholic Church in the 1960s and 1970s Yann Bevant Reconstruction de l’Église catholique en République d’Irlande Déborah Vandewoude Church and State in Ireland (1922-2013): Contrasting Perceptions of Humanity Catherine Maignant Dark walled up with stone: contrasting images of Irish Catholicism Colum Kenny Représentations littéraires des changements religieux “They all seem to have inherited the horrible ugliness and sewer filth of sex”: Catholic Guilt in Selected Works by John McGahern (1934-2006) Eamon Maher Seán Dunne’s The Road to Silence: An Anomalous Spiritual Autobiography? James S. -

Cultural Perspectives on Globalisation and Ireland

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin AFIS (Association of Franco-Irish Studies) Books Publications 2011 Cultural Perspectives on Globalisation and Ireland Eamon Maher Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/afisbo Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Maher, Eamon, "Cultural Perspectives on Globalisation and Ireland" (2011). Books. 6. https://arrow.tudublin.ie/afisbo/6 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the AFIS (Association of Franco-Irish Studies) Publications at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Cultural Perspectives on Globalisation and Ireland Reimagining Ireland Volume 5 Edited by Dr Eamon Maher Institute of Technology, Tallaght PETER LANG Oxford • Bern • Berlin • Bruxelles • Frankfurt am Main • New York • Wien Eamon Maher (ed.) Cultural Perspectives on Globalisation and Ireland PETER LANG Oxford • Bern • Berlin • Bruxelles • Frankfurt am Main • New York • Wien Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche National- bibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at ‹http://dnb.ddb.de›. A catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: Maher, Eamon. Cultural perspectives on globalisation and Ireland / Eamon Maher. p. cm. -- (Reimagining Ireland ; 5) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-3-03911-851-9 (alk. -

Loughcutra Event May2015.Pdf

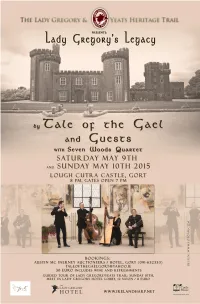

Gala Event 'Lady Gregory's Legacy' in Lough Cutra Castle, Gort presented by The Yeats and Lady Gregory Heritage Trail, Galway with Tale of the Gael and The Seven Woods Quartet. Saturday May 9th and Sunday May 10th 2015 as part of the Yeats 2015 celebrations. The castle with its magnificent lake views and elegant interior is a private home, but opens its doors for this event in a style reminiscent of the gracious hospitality offered to all by Lady Gregory herself when she lived on the neighbouring estate of Coole Park. Often viewed through the achievements of others, this specially comissioned performance brings Lady Augusta Gregory to the fore. Distinctly Edwardian at first glance, Augusta’s complex personality is as fascinating as her legacy is astounding. Tale of the Gael are no strangers to the task of presenting Ireland’s history and culture through music, anecdote, poetry and song. A core of traditional music tempered by classical overtones make a perfect backdrop for the life of Lady Gregory, who supported nationalism through her work, but who came from a background with strong colonial roots, and was married to a former British MP. The group has served Ireland as cultural ambassadors on many occasions, with performances in Europe, Africa, and the US and are much in demand wherever an authentic, yet elegant portrayal of Ireland’s culture and music is required. They are joined by The Seven Woods Quartet from Coole Music in Gort. Mickey Dunne uilleann pipes/ fiddle Robert Tobin silver flute/whistle Catherine Rhatigan harp / text Deirdre Starr voice Tricia Keane voice Dave Aebli bouble bass/bouzuki Prannie Rhatigan percussion Tickets are €30 euro, and include refreshments and finger food.