Pindar and Yeats: the Mythopoeic Vision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

18_121726-bindex.qxp 4/17/09 2:59 PM Page 486 Index See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX Ardnagashel Estate, 171 Bank of Ireland The Ards Peninsula, 420 Dublin, 48–49 Abbey (Dublin), 74 Arigna Mining Experience, Galway, 271 Abbeyfield Equestrian and 305–306 Bantry, 227–229 Outdoor Activity Centre Armagh City, 391–394 Bantry House and Garden, 229 (Kildare), 106 Armagh Observatory, 394 Barna Golf Club, 272 Accommodations. See also Armagh Planetarium, 394 Barracka Books & CAZ Worker’s Accommodations Index Armagh’s Public Library, 391 Co-op (Cork City), 209–210 saving money on, 472–476 Ar mBréacha-The House of Beach Bar (Aughris), 333 Achill Archaeological Field Storytelling (Wexford), Beaghmore Stone Circles, 446 School, 323 128–129 The Beara Peninsula, 230–231 Achill Island, 320, 321–323 The arts, 8–9 Beara Way, 230 Adare, 255–256 Ashdoonan Falls, 351 Beech Hedge Maze, 94 Adrigole Arts, 231 Ashford Castle (Cong), 312–313 Belfast, 359–395 Aer Lingus, 15 Ashford House, 97 accommodations, 362–368 Agadhoe, 185 A Store is Born (Dublin), 72 active pursuits, 384 Aillwee Cave, 248 Athlone, 293–299 brief description of, 4 Aircoach, 16 Athlone Castle, 296 gay and lesbian scene, 390 Airfield Trust (Dublin), 62 Athy, 102–104 getting around, 362 Air travel, 461–468 Athy Heritage Centre, 104 history of, 360–361 Albert Memorial Clock Tower Atlantic Coast Holiday Homes layout of, 361 (Belfast), 377 (Westport), 314 nightlife, 386–390 Allihies, 230 Aughnanure Castle (near the other side of, 381–384 All That Glitters (Thomastown), -

Hydrogeology of the Burren and Gort Lowlands

KARST HYDROGEOLOGY OF THE BURREN UPLANDS / GORT LOWLANDS Field Guide International Association of Hydrogeologists (IAH) Irish Group 2019 Cover page: View north across Corkscrew Hill, between Lisdoonvarna and Ballyvaughan, one of the iconic Burren vistas. Contributors and Excursion Leaders. Colin Bunce Burren and Cliffs of Moher UNESCO Global Geopark David Drew Department of Geography, Trinity College, Dublin Léa Duran Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, Trinity College, Dublin Laurence Gill Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, Trinity College, Dublin Bruce Misstear Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, Trinity College, Dublin John Paul Moore Fault Analysis Group, Department of Geology, University College Dublin and iCRAG Patrick Morrissey Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, Trinity College, Dublin and Roughan O‘Donovan Consulting Engineers David O’Connell Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, Trinity College, Dublin Philip Schuler Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, Trinity College, Dublin Luka Vucinic Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, Trinity College, Dublin and iCRAG Programme th Saturday 19 October 10.00 Doolin Walk north of Doolin, taking in the coast, as well as the Aillwee, Balliny and Fahee North Members, wayboards, chert beds, heterogeneity in limestones, joints and veins, inception horizons, and epikarst David Drew and Colin Bunce, with input from John Paul Moore 13.00 Lunch in McDermotts Bar, Doolin 14.20 Murrooghtoohy Veins and calcite, relationship to caves, groundwater flow and topography John Paul Moore 15.45 Gleninsheen and Poll Insheen Holy Wells, epikarst and hydrochemistry at Poll Insheen Bruce Misstear 17.00 Lisdoonvarna Spa Wells Lisdoonvarna history, the spa wells themselves, well geology, hydrogeology and hydrochemistry, some mysterious heat .. -

Carnaval Do Galway the Brazilian Community in Gort, 1999-2006

Irish Migration Studies in Latin America Vol. 4, No. 3: July 2006 www.irlandeses.org Carnaval do Galway The Brazilian Community in Gort, 1999-2006 By Claire Healy Gort Inse Guaire, or Gort, lies just north of the border with County Clare in south County Galway in the West of Ireland, and has a population of about three thousand people. It is situated between the Slieve Aughty mountains and the unique karstic limestone landscape of the Burren, in the heartland of the countryside made famous by Lady Augusta Gregory and the poet W.B. Yeats in nearby Coole Park and Thoor Ballylee. Nineteenth- century Gort was a thriving market town providing a commercial centre for its fertile agricultural hinterland. A Sabor Brasil shop on Georges St., Gort market was held in the market (Claire Healy 2006) square every Saturday, and sheep, cattle and pig fairs were held regularly. A cavalry barracks accommodating eight British officers and eighty-eight soldiers was situated near the town and the Dublin and Limerick mail coaches trundled along the main street. [1] Throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, day labourers congregated on the market square in the centre of town hoping for a day’s seasonal work on a farm. By the 1990s, the town had become a quiet and sparsely populated shadow of its former self. Many of the shops along the main street, Georges Street, were shutting their doors for the last time, and the town was familiar to most Irish people only as a brief stop on the bus route from Galway to the southern cities of Cork and Limerick. -

A Sunny Day in Sligo

June 2009 VOL. 20 #6 $1.50 Boston’s hometown journal of Irish culture. Worldwide at bostonirish.com All contents copyright © 2009 Boston Neighborhood News, Inc. Picture of Grace: A Sunny Day in Sligo The beauty of the Irish landscape, in this case, Glencar Lough in Sligo at the Leitrim border, jumps off the page in this photograph by Carsten Krieger, an image taken from her new book, “The West of Ireland.” Photo courtesy Man-made Images, Donegal. In Charge at the BPL Madame President and Mr. Mayor Amy Ryan is the multi- tasking president of the venerable Boston Pub- lic Library — the first woman president in the institution’s 151-year his- tory — and she has set a course for the library to serve the educational and cultural needs of Boston and provide access to some of the world’s most historic records, all in an economy of dramatic budget cuts and a significant rise in library use. Greg O’Brien profile, Page 6 Nine Miles of Irishness On Old Cape Cod, the nine-mile stretch along Route 28 from Hyannis to Harwich is fast becom- ing more like Galway or Kerry than the Cape of legend from years ago. This high-traffic run of roadway is dominated by Irish flags, Irish pubs, Irish restaurants, Irish hotels, and one of the fast- est-growing private Irish Ireland President Mary McAleese visited Boston last month and was welcomed to the city by Boston clubs in America. Mayor Tom Menino. Also pictured at the May 26 Parkman House event were the president’s husband, BIR columnist Joe Dr. -

A New Epic Fragment on Achilles' Helmet?

Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists 49 (2012) 7-14 A New Epic Fragment on Achilles’ Helmet?1 C. Michael Sampson University of Manitoba Abstract Edition of a small scrap from the Princeton collection containing fragmentary epic hexameters, ascribed to the cyclic Aethiopis of Arctinus or the Little Iliad on the basis of its contents, which most plausibly involve the death of Achilles (with possible echoes of that of Penthesilea). This small fragment from the Princeton collection preserves a lovely slop- ing oval hand whose uncials are roughly bilinear but tiny – typically in the vicinity of 3 mm tall. The uprights of kappa (ll. 5; 11) and iota (ll. 3; 7; 10) are occasionally adorned with a decorative serif, and the loops of omicron and rho are particularly small (a mere 1-1.5 mm), but the hand is otherwise consistent with the “formal mixed” style described by Turner, with narrow epsilon, theta, omicron, and sigma but comparatively wide and squat forms of pi, eta, nu, and mu.2 The label “formal,” however, is not exactly ideal; close parallels are found in the small, rapid hands of the latter half of the second century (occasionally termed “informal” by their editors), to which date and category I would assign this hand as well.3 So broad are the shapes of eta, nu, and pi, in fact, that they 1 I am happy to acknowledge the support of the American Council of Learned So- cieties and The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for the New Faculty Fellows award under whose auspices this research was undertaken, as well as the cooperation of Dr. -

"The Wild Beauty I Found There": Plath's Connemara Gail Crowther

208 "The wild beauty I found there": Plath's Connemara Gail Crowther The yellows and browns of Connemara are wild. Undulating hills and loughs and inlets where the Atlantic creams over black rocks and the sky and sea join, held together by flat white clouds. The pungent gorse bushes and the roadside fuschias and mallows and spikey hedgerows border peat bogs and marshy brown puddles of water. Megalithic tombs balance their stones atop slight mounds and small cottages huddle in sheltered cut out gardens against the mountains and the sea. Wild Connemara is where Sylvia Plath initially chose to escape in the upset of her final year. A brief visit to Cleggan to stay with the poet Richard Murphy in September 1962 was enough to captivate her. In Murphy's words: "She seemed to have fallen in love with Connemara at first sight" (Bitter Fame 350). This paper aims to explore Plath's time in Connemara, the places she visited and her plans to winter there from December 1962 until late February 1963. While I will not be discussing at any great length the details of her visit there (this has already been done by her host Richard Murphy elsewhere), I will be drawing on Plath's own impression of Connemara using both published and unpublished letters that she wrote to family and friends. 1 Since Plath's journals from this time are lost/missing, letters are the main first-hand sources of information from this period in Plath's life. Following Plath's trail on a recent visit to 1 See Appendix III in Bitter Fame (348-359) and Murphy's autobiography The Kick. -

A Dictionary of Mythology —

Ex-libris Ernest Rudge 22500629148 CASSELL’S POCKET REFERENCE LIBRARY A Dictionary of Mythology — Cassell’s Pocket Reference Library The first Six Volumes are : English Dictionary Poetical Quotations Proverbs and Maxims Dictionary of Mythology Gazetteer of the British Isles The Pocket Doctor Others are in active preparation In two Bindings—Cloth and Leather A DICTIONARY MYTHOLOGYOF BEING A CONCISE GUIDE TO THE MYTHS OF GREECE AND ROME, BABYLONIA, EGYPT, AMERICA, SCANDINAVIA, & GREAT BRITAIN BY LEWIS SPENCE, M.A. Author of “ The Mythologies of Ancient Mexico and Peru,” etc. i CASSELL AND COMPANY, LTD. London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne 1910 ca') zz-^y . a k. WELLCOME INS77Tint \ LIBRARY Coll. W^iMOmeo Coll. No. _Zv_^ _ii ALL RIGHTS RESERVED INTRODUCTION Our grandfathers regarded the study of mythology as a necessary adjunct to a polite education, without a knowledge of which neither the classical nor the more modem poets could be read with understanding. But it is now recognised that upon mythology and folklore rests the basis of the new science of Comparative Religion. The evolution of religion from mythology has now been made plain. It is a law of evolution that, though the parent types which precede certain forms are doomed to perish, they yet bequeath to their descendants certain of their characteristics ; and although mythology has perished (in the civilised world, at least), it has left an indelible stamp not only upon modem religions, but also upon local and national custom. The work of Fruger, Lang, Immerwahr, and others has revolutionised mythology, and has evolved from the unexplained mass of tales of forty years ago a definite and systematic science. -

Hephaestus the Magician and Near Eastern Parallels for Alcinous' Watchdogs , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 28:3 (1987:Autumn) P.257

FARAONE, CHRISTOPHER A., Hephaestus the Magician and Near Eastern Parallels for Alcinous' Watchdogs , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 28:3 (1987:Autumn) p.257 Hephaestus the Magician and Near Eastern Parallels for Alcinous' Watchdogs Christopher A. Faraone s ODYSSEUS enters the palace of the Phaeacian king he stops to A marvel at its richly decorated fa9ade and the gold and silver dogs that stand before it (Od. 7.91-94): , ~,t: I () \, I , ")" XPVCHLOL u EKanp E KaL apyvpEoL KVVES l1CTav, C 'll I 'll ovs'" ·'HA-.'t'aLCTTOS' ETEV~" EV LuVL?1CTL 7rpa7rLUECTCTL oWJJ.a <pvAaCTCTEJJ.EvaL JJ.EyaA~TopoS' ' AAKWOOLO, a'() avaTOVS'I OVTaS'" KaL\ aYl1pwS'')',' l1JJ.aTa 7raVTa.I On either side [sc. of the door] there were golden and silver dogs, immortal and unaging forever, which Hephaestus had fashioned with cunning skill to protect the home of Alcinous the great hearted. All the scholiasts give the same euhemerizing interpretation: the dogs were statues fashioned so true to life that they seemed to be alive and were therefore able to frighten away any who might attempt evil. Eustathius goes on to suggest that the adjectives 'undying' and 'un aging' refer not literally to biological life, but rather to the durability of the rust-proof metals from which they were fashioned, and that the dogs were alleged to be the work of Hephaestus solely on account of their excellent workmanship. 1 Although similarly animated works of Hephaestus appear elsewhere in Homer, such as the golden servant girls at Il. 18.417-20, modern commentators have also been reluctant to take Homer's description of these dogs at face value. -

RELIGION in HERODOTUS Jon D. Mikalson Although It Is Regularly Ignored, Dismissed, Or Disparaged by Both Ancient and Modern Hist

CHAPTER EIGHT RELIGION IN HERODOTUS Jon D. Mikalson Although it is regularly ignored, dismissed, or disparaged by both ancient and modern historians, Herodotus explicitly offers also a reli gious explanation of the causes and outcome of the Persian inva sions. I In 499 BC a small force of Greeks, including Athenians, attacked Sardis, a principal city of the Persian empire, and in the course of the attack they accidently burned down the sanctuary of the goddess Cybebe (S.101- 102.1). When King Darius first heard of it, 'he took a bow, fitted an arrow to it, and shot the arrow into the sky. As he did, he prayed, "Zeus, grant me to take vengeance on the Athenians ... '" (S.lOS). It was the burning of Cybebe's sanc tuary that the Persians then used as an excuse for burning sanctu aries throughout the lands of hostile Greek cities for the next eighteen years (S.102.l; cf. 6.l0l.3 and 7.8.P).2 These included, after the Ionian Revolt, Apollo's temple and oracle at Didyma, and the sanc tuaries of all the revolting Ionian cities and islands of Asia Minor except Samos (6.l9.3, 2S, and 32). Later Datis on his way to Marathon in 490 burned the sanctuaries of Naxos and Eretria (6.96 and 10l.3). And in the second invasion Xerxes destroyed the sanctuaries in twelve Phocian cities, including Apollo's oracle at Abae (8.32.2- 33). Had he had his way, Xerxes would have had Delphi destroyed too (8.3S- 9). -

Loughcutra Event May2015.Pdf

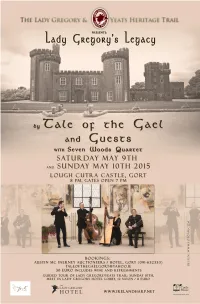

Gala Event 'Lady Gregory's Legacy' in Lough Cutra Castle, Gort presented by The Yeats and Lady Gregory Heritage Trail, Galway with Tale of the Gael and The Seven Woods Quartet. Saturday May 9th and Sunday May 10th 2015 as part of the Yeats 2015 celebrations. The castle with its magnificent lake views and elegant interior is a private home, but opens its doors for this event in a style reminiscent of the gracious hospitality offered to all by Lady Gregory herself when she lived on the neighbouring estate of Coole Park. Often viewed through the achievements of others, this specially comissioned performance brings Lady Augusta Gregory to the fore. Distinctly Edwardian at first glance, Augusta’s complex personality is as fascinating as her legacy is astounding. Tale of the Gael are no strangers to the task of presenting Ireland’s history and culture through music, anecdote, poetry and song. A core of traditional music tempered by classical overtones make a perfect backdrop for the life of Lady Gregory, who supported nationalism through her work, but who came from a background with strong colonial roots, and was married to a former British MP. The group has served Ireland as cultural ambassadors on many occasions, with performances in Europe, Africa, and the US and are much in demand wherever an authentic, yet elegant portrayal of Ireland’s culture and music is required. They are joined by The Seven Woods Quartet from Coole Music in Gort. Mickey Dunne uilleann pipes/ fiddle Robert Tobin silver flute/whistle Catherine Rhatigan harp / text Deirdre Starr voice Tricia Keane voice Dave Aebli bouble bass/bouzuki Prannie Rhatigan percussion Tickets are €30 euro, and include refreshments and finger food. -

Torresson Umn 0130E 21011.Pdf

The Curious Case of Erysichthon A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Elizabeth Torresson IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Advisor: Nita Krevans December 2019 © Elizabeth Torresson 2019 Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank the department for their support and especially the members of my committee: Nita Krevans, Susanna Ferlito, Jackie Murray, Christopher Nappa, and Melissa Harl Sellew. The seeds of this dissertation were planted in my senior year of college when Jackie Murray spread to me with her contagious enthusiasm a love of Hellenistic poetry. Without her genuine concern for my success and her guidance in those early years, I would not be where I am today. I also owe a shout-out to my undergraduate professors, especially Robin Mitchell-Boyask and Daniel Tompkins, who inspired my love of Classics. At the University of Minnesota, Nita Krevans took me under her wing and offered both emotional and intellectual support at various stages along the way. Her initial suggestions, patience, and encouragement allowed this dissertation to take the turn that it did. I am also very grateful to Christopher Nappa and Melissa Harl Sellew for their unflagging encouragement and kindness over the years. It was in Melissa’s seminar that an initial piece of this dissertation was begun. My heartfelt thanks also to Susanna Ferlito, who graciously stepped in at the last minute and offered valuable feedback, and to Susan Noakes, for offering independent studies so that I could develop my interest in Italian language and literature. -

The Ears of Hermes

The Ears of Hermes The Ears of Hermes Communication, Images, and Identity in the Classical World Maurizio Bettini Translated by William Michael Short THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRess • COLUMBUS Copyright © 2000 Giulio Einaudi editore S.p.A. All rights reserved. English translation published 2011 by The Ohio State University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bettini, Maurizio. [Le orecchie di Hermes. English.] The ears of Hermes : communication, images, and identity in the classical world / Maurizio Bettini ; translated by William Michael Short. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1170-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1170-4 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9271-6 (cd-rom) 1. Classical literature—History and criticism. 2. Literature and anthropology—Greece. 3. Literature and anthropology—Rome. 4. Hermes (Greek deity) in literature. I. Short, William Michael, 1977– II. Title. PA3009.B4813 2011 937—dc23 2011015908 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1170-0) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9271-6) Cover design by AuthorSupport.com Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Garamond Pro Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American Na- tional Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Translator’s Preface vii Author’s Preface and Acknowledgments xi Part 1. Mythology Chapter 1 Hermes’ Ears: Places and Symbols of Communication in Ancient Culture 3 Chapter 2 Brutus the Fool 40 Part 2.