Hispanic Migrant Labor in Oregon, 1940-1990

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FARMWORKER JUSTICE MOVEMENTS (4 Credits) Syllabus Winter 2019 Jan 07, 2019 - Mar 15, 2019

1 Ethnic Studies 357: FARMWORKER JUSTICE MOVEMENTS (4 credits) Syllabus Winter 2019 Jan 07, 2019 - Mar 15, 2019 Contact Information Instructors Office, Phone & Email Ronald L. Mize Office Hours: Wed 11:30-12:30, or by Associate Professor appointment School of Language, Culture and Society 541.737.6803 Office: 315 Waldo Hall Email [email protected] Class Meeting: Wednesdays, 4:00 pm - 7:50 pm, Learning Innovation Center (LINC) 360, including three off- campus service/experiential learning sessions. The course is four credits based on number of contact hours for lecture/discussion and three experiential learning sessions. Course Description: Justice movements for farmworkers have a long and storied past in the annals of US history. This course begins with the 1960s Chicano civil rights era struggles for social justice to present day. Focus on the varied strategies of five farmworker justice movements: United Farm Workers, Farm Labor Organizing Committee, Pineros y Campesinos Unidos Noroeste, Migrant Justice, and the Coalition of Immokalee Workers. This course was co-designed with a founder of PCUN, Larry Kleinman, who actively co-leads the course as his schedule allows. The course is structured around the question of the movement and its various articulations. Together, we will cover some central themes and strategies that comprise the core of farm worker movements but the course is designed to allow you, the student, to explore other articulations you find personally relevant or of interest. This course is designated as meeting Difference, Power, and Discrimination requirements. Difference, Power, and Discrimination Courses Baccalaureate Core Requirement: ES357 “Farmworker Justice Movements” fulfills the Difference, Power, and Discrimination (DPD) requirement in the Baccalaureate Core. -

Farm Labor, Reproductive Justice: Migrant Women Farmworkers in the US

Galarneau Charlene Galarneau, PhD, AM, MAR, is Assistant Farm labor, reproductive justice: Professor in the Women’s and Migrant women farmworkers in the US Gender Studies Department at Wellesley College, Wellesley, Charlene Galarneau MA, USA. Abstract Please address correspon- dence to the author, at: Little is known about the reproductive health of women migrant farmworkers in the Women’s and Gender Studies US. The health and rights of these workers are advanced by fundamental human Department, 106 Central rights principles that are sometimes conceptually and operationally siloed into three Street, Wellesley College, approaches: reproductive health, reproductive rights, and reproductive justice. I focus Wellesley, MA, USA 02481, on the latter framework, as it lends critical attention to the structural oppression email: cgalarne@wellesley. central to poor reproductive health, as well as to the agency of communities organiz- edu. ing and leading efforts to improve their health. I review what is known about these women’s reproductive health; identify three realms of reproduction oppression affecting Competing interests: None their reproductive health: labor/occupational conditions, health care, and social rela- declared. tions involving race, immigration and fertility; and then highlight some current efforts at women farmworker-directed change. Finally, I make several analytical observations Copyright © 2013 Galarneau. that suggest the importance of the reproductive justice framework to broader discus- This is an open access article sions of migrant worker justice and its role in realizing their right to health. distributed under the terms of the Creative Common Introduction Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecom- Summer 1978 in rural Colorado: Luz was 14 years old, working in the melon mons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), fields, and pregnant. -

Mexican-Americans in the Pacific Northwest, 1900--2000

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2006 The struggle for dignity: Mexican-Americans in the Pacific Northwest, 1900--2000 James Michael Slone University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Slone, James Michael, "The struggle for dignity: Mexican-Americans in the Pacific Northwest, 1900--2000" (2006). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2086. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/4kwz-x12w This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE STRUGGLE FOR DIGNITY: MEXICAN-AMERICANS IN THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST, 1900-2000 By James Michael Slone Bachelor of Arts University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2000 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in History Department of History College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1443497 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Understanding Mexican Migrant Civil Society

Mapping Mexican Migrant Civil Society 1 Jonathan Fox Latin American and Latino Studies Department University of California, Santa Cruz [email protected] comments welcome This is a background paper prepared for: Mexican Migrant Civic and Political Participation November 4-5, 2005 Co-sponsored by the Latin American and Latino Studies Department University of California, Santa Cruz and the Mexico Institute and Division of United States Studies Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars www.wilsoncenter.org/migrantparticipation 1 This paper draws on ideas presented in Fox (2004, 2005a, 2005b, and 2005c) and Fox and Rivera-Salgado (2004). The research was made possible by grants from the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations, as well a 2004-2005 fellowship from the Woodrow Wilson Center. This paper was informed by ongoing conversations with colleagues too numerous to thank here, but I would like to express my special appreciation for input from Xóchitl Bada and Gaspar Rivera-Salgado. Summary: This paper “maps” the diverse patterns of Mexican migrant social, civic and political participation in the US, reviews current research and poses analytical questions informed by a binational perspective. While some migrants are more engaged with organizations focused on the US, others participate more in groups that are concerned with Mexico. At the same time, some Mexican migrants are working to become full members of both US and Mexican society, constructing practices of "civic binationality" that have a great deal to teach us about new forms of immigrant integration into US society. These different forms of participation are analyzed through the conceptual lens of “migrant civil society,” which includes four migrant-led arenas: membership organizations, NGOs, communications media and autonomous public spheres. -

December, 2004

UFW DOCUMENTATION PROJECT ONLINE DISCUSSION December 2004 and January 2005 Kathy Lynch Murguia, 12/1/04 RE: Closure Kathy Murguia 1965-1983 As we move to the final days of the Listserve, I am bringing closure to a huge chunk of my life. I don't know about anyone else, but I do reflect back with varied emotions and interpretations of events. It began so simple and it ended up being so complicated. What was public became personal . Thoughts became projected into possibilities and threats. What was personal became public in that it became a test of loyalty. The lines became blurred; boundaries confused. We all participated in this blurring of reality. We hurt each other in our misunderstandings. I had hoped we were headed somewhere...I did believe the farmworkers needed a union. El Movimiento was a beginning. It came as a result of what Cesar called "viva swells". It was the structure that became problematic, and its tolerance for criticism and its ability to resolve internal conflict that became lost in a fog of meaning. Doug you are right. As one that was there at the beginning. I would venture to say we lost the willingness to talk to each other. Yes Abby, the Game facilitated this level of honesty. Mary, I do wish we could time travel into the next decade and be renewed. Marshall, in this interregnum will Cesar's and our dreams survive? What lessons have we learned? I would name one. Responsibility rests within. We invest in history and we have the obligation/ duty to defend what we know to be our experience; to find our voice and to speak, trusting our words, directing these words to those who need to hear what we have to say. -

Fish Get Better Poison Protections Than Workers by Lisa Arkin, Exec

Photo by Carla Hervert Fish get better poison protections than workers by Lisa Arkin, Exec. Director By state law, salmon and steelhead swimming upstream few require buffer zones for fish protection! These are protected by a 300 foot no-spray buffer from pesticides are known to cause cancer, brain damage, exposure to agricultural pesticides; yet farm workers irreversible eye damage, Parkinson’s Disease and have few, if any, protections from these same pesticides. devastating birth defects. Yes, you read that right. Under a new law proposed by Oregon’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), crop dusters, helicopters and pressurized air blast equipment do not observe a no-spray buffer zone within housing and living areas – the places where workers are carrying out the daily activities of life – cooking and eating, showering, hanging out laundry, and relaxing with their spouses and children. Instead, OSHA is telling workers and their families to hide inside their shacks to avoid getting sprayed. This is inhumane and only perpetuates worker exploitation. Community Voices. Omitting the voices of the impact- OSHA registers over 300 worker housing complexes in ed community is unfair and biased. Beyond Toxics held Oregon. Hundreds more fall below the radar. Hidden OSHA accountable for their original plan to omit worker from view, tucked away in the pear and apple orchards advocates from being at the table during rule making of Hood River and Jackson County, are the one-room and prevent workers from attending public hearings. shacks of cinder block or worn-out wood siding where We successfully demanded that farm workers play a key workers and their families are housed. -

April 10, 2003 the Honorable Orrin Hatch 104 Hart

April 10, 2003 The Honorable Orrin Hatch 104 Hart Senate Office Building Washington, D.C. 20510 The Honorable Richard Durbin 332 Dirksen Senate Office Building Washington, D.C. 20510 Dear Senator Hatch and Senator Durbin: Representing a broad alliance of educators, businesses, labor groups, civil rights organizations, faith-based groups, children and youth groups, and various community-based organizations from across the country, we write to express our strong support for the DREAM Act. You introduced this important legislation in the 107th Congress to address the federal barriers to education and work confronted by the U.S.-raised children of immigrants lacking immigration status, as well as the challenges that such students face in adjusting their immigration status. We appreciate your leadership on this issue and look forward to the upcoming reintroduction of this critical legislation. As educators, potential employers, and advocates of these students, we believe that the DREAM Act is the right thing to do, both for the young people whose lives are in the balance and for the rest of us. The DREAM Act appropriately recognizes that these young people have done nothing wrong. Despite the pressures to do otherwise, these students have stayed in school and out of trouble. This important legislation acknowledges that these students will be better prepared and able to contribute to our joint future if they are permitted to complete their education and work legally. In turn, our local, state, and national economy will benefit from their increased contributions into or tax and social insurance system, as will all of us who come into contact with these young people in years to come: the children they teach, the patients they care for, the businesses that employ them, the communities they lead, and others. -

Organizations Supporting Overtime Pay for Farm Workers AFL-CIO

Organizations Supporting Overtime Pay for Farm Workers AFL-CIO African American Ministers in Action Alianza Nacional de Campesinas American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) American Federation of Teachers (AFT) Asian Americans Advancing Justice | AAJC Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance Association Farmworker Opportunity Programs California Council of Churches IMPACT Casa de Esperanza: National Latin@ Network for Healthy Families and Communities Center for Community Change Center for Popular Democracy Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy Centro de los Derechos del Migrante, Inc. Coalition of Immokalee Workers Coalition on Human Needs Columbia Legal Services Communications Workers of America Community to Community Development CRLA Foundation Disciples for Public Witness Disciples Refugee & Immigration Ministries (Christian Church, Disciples of Christ) Earthjustice Eastern Regional Alliance for Farmworker Advocates Economic Policy Institute El Comite de Apoyo a los Trabajadores Agrícolas Equal Justice Society Equal Rights Advocates Fair Immigration Reform Movement (FIRM) Farm Worker Ministry Northwest Farmworker Association of Florida Farmworker Justice Feminist Majority FLOC Florida Legal Services, Inc. Food & Water Watch Food Empowerment Project Franciscan Action Network Futures Without Violence Hispanic Affairs Project Hispanic Federation Housing Assistance Council Impact Fund International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace, and Agricultural Implement Workers of America, UAW Jobs With -

Program Eastern Washington University Portland State University Portland

RISTED BY THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST FOCO / • - .aM-r '.'.r ;NTY-SEVENTH ANNUAL NATIONAL CONFERENCE »w - -;>; 'tj' SABIDU YOUTH, CO ;> A'.ST- ;*•-/> r' •#• rvc^irm/naccs / /W i»> • >»Miitfi.Mi).Vriiiiiiiiii.. II I TOwk HILTON • POBTLAND OREOO^ Loeo OfSIStti ANDII£S BAIfeAJAS / WEB PROORAMMiNO. SANTOS CASH CONFERENCE EVENT MAP FOR HILTON HOTEL DIRECTORS THE TWENTY-SEVENTH ANNUAL SENATE EXECUTIVE B B NATIONAL CONFERENCE THIRD LEVEL PAVILION BALLROOM ^ EAST KAVILIUN I i BALLROOM / \ \ "EST II i J II ]mi•JII— MJ LB TiB• •} (i- 1J .t PLAZA LEVEL 1 FT PARLOR F A PARLOR GRAND BALLROOM L/LL • »ARLOR I ' C • SABIDURIA, LUCHA Y LIBERACION: YOUTH, COMMUNITY S. CULTURE EN EL NUEVO SOL B BALLROOM LEVEL TABLE OF CONTENTS I The National Association for Chicana and Chicano Studies 1 INTRODUCTIONS (NACCS) was founded in 1972 to encourage research to further the political actualization of the Chicana and Chicano community. NACCS calls for committed, critical, and rigorous 1 Welcome Letters 2 1 research. NACCS was envisioned not as an academic 1 Dedications k 1 embellishment, but as a structure rooted in political life. 6 1 From its inception, NACCS presupposed a divergence from 1 National Coordinating Confimittee mainstream academic research. We recognize that 1 Conference Organizing Connnnittee 7 1 mainstream research, based on an integrationist perspective emphasizing consensus, assimilation, and the legitimacy of 1 Conference Sponsors 8 1 society's institutions, has obscured and distorted the 1 Vendors and Exhibitors 9 1 significant historical roles class, race, gender, sexuality and group interests have played in shaping our existence as a 1 Hotel Infornnation 10 1 people. -

BIPOC Timeline (For PDF)

Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) Timeline of Lane County, Oregon Year Label Description Source The US Congress passes the Northwest Ordinance. The Utmost 1787 Good Faith Law states that Native American land and property A Chronology of Racial Exclusion And Civil Rights Law. Obtained from the Northwest Ordinance shall never be taken from them without their consent. Lane County History Museum, 301.45 Part II Marcus Lopez, cabin boy of Captain Robert Gray, becomes the 1788 first person of African descent known to have set foot on A Chronology of Racial Exclusion And Civil Rights Law. Obtained from the Marcus Lopez arrives in Oregon Oregon soil. Lane County History Museum, 301.45 Part II US citizenship only for a "free white A Chronology of Racial Exclusion And Civil Rights Law. Obtained from the 1790 Person." Federal law‐ US citizenship only for a "free white Person." Lane County History Museum, 301.45 Part II York, William Clark's slave, comes west with Lewis and Clarks', A Chronology of Racial Exclusion And Civil Rights Law. Obtained from the 1805 York comes West Corps of Discovery. Lane County History Museum, 301.45 Part II Looking Back In Order to Move Forward an often untold history affecting Oregon's Past, Present, and Future. Compiled by Elaine Rector as part of Methodist missionaries come to Oregon led by Jason Lee. CFEE (Coaching for Educational Equity) and LFEE (Leading for Educational 1830 Unfortunately the missionaries and the natives suffered from a Equity), November 2009. Retrieved from horrendous epidemic which killed 70% of the Kalapuyans the http://www.osba.org/~/media/Files/Event%20Materials/AC/2009/101_Hist Methodist missionaries missionaries had come to “save.” ory%20of%20Race%20in%20Oregon.pdf 1843 Settlers in Oregon Territory adopt the Organic Act to form the A Chronology of Racial Exclusion And Civil Rights Law. -

Understanding the Immigrant Experience in Oregon Research, Analysis, and Recommendations from University of Oregon Scholars

Understanding the Immigrant Experience in Oregon Research, Analysis, and Recommendations from University of Oregon Scholars Robert Bussel, Editor Understanding the Immigrant Experience in Oregon Research, Analysis, and Recommendations from University of Oregon Scholars Editor Lara Skinner, Graduate Teaching Fellow, LERC Robert Bussel, Associate Professor of History and and Department of Sociology Director, Labor Education and Research Center Lynn Stephen, Distinguished Professor, Department of Anthropology Contributing authors Spanish editing and translation Michael Aguilera, Assistant Professor of Sociology J. Mark Eddy, Research Associate, Oregon Social Marcela Mendoza, Adjunct Assistant Professor and Learning Center, and Courtesy Research Associate, Research Associate, Department of Anthropology Department of Psychology Magali Morales, Crystal Clear Translation Justyna Goworowska, Graduate Teaching Fellow, Department of Geography Illustrations Susan Hardwick, Professor of Geography Roberto Arroyo, Graduate Teaching Fellow, Ken Kato, Assistant Director of the InfoGraphics Department of Romance Languages Laboratory, and Department of Geography Mauricio Magana, Graduate Teaching Fellow, Photographs Center for the Study of Women in Society Center for Intercultural Organizing Charles Martinez, Jr., Research Scientist, Oregon Social Learning Center, and Associate Professor, Susan Hardwick, Professor of Geography College of Education Rowanne Haley, Immigration and Refugee Heather McClure, Research Associate, Oregon Community Organization Social -

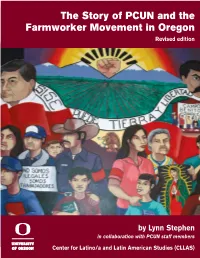

The Story of PCUN and the Farmworker Movement in Oregon Revised Edition

The Story of PCUN and the Farmworker Movement in Oregon Revised edition by Lynn Stephen in collaboration with PCUN staff members Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies (CLLAS) The STory of PCUN aNd The farmworker movement iN oregoN Revised and Expanded by Lynn Stephen in collaboration with PCUN staff and members Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies (CLLAS) Eugene, Oregon July 2012 Front cover photograph: Mural in the meeting hall of PCUN’s Risberg Hall headquarters, Woodburn, Oregon. Title page photograph: Tenth Anniversary Organizing Campaign, Brooks, Oregon, June 1995. Back cover: Mural on back wall of the meeting hall of PCUN’s Risberg Hall headquarters, Woodburn, Oregon. © Lynn Stephen and pCUn, 2012 Written by Lynn Stephen in collaboration with PCUN staff and members Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies (CLLAS) 6201 University of Oregon Eugene, OR 97403-6201 (541)346-5286 [email protected] http://cllas.uoregon.edu July 2012 Pineros y Campesinos Unidos del Noroeste (PCUN) 300 Young Street Woodburn OR 97071 (503) 982-0243 www.pcun.org [email protected] Production Alice Evans Research Dissemination Specialist Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies Proofing Eli Meyer, Assistant Director, CLLAS June Koehler, Research Assistant, CLLAS All photographs credited to PCUN unless otherwise noted The University of Oregon is an equal-opportunity, affirmative- action institution committed to cultural diversity and compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act. This publication will be made available in accessible formats upon request. 750 CopieS 2 The Story of PCUN and the Farmworker Movement in Oregon Child in the field, 1995.