Hypertensive Kidney Disease” Fit?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High B1a0d Pressure and Its Treatment in General

HIGH B1A0D PRESSURE AND ITS TREATMENT IN GENERAL PRACTICE WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO A SERIES OF 100 CASES TREATED BY THE AUTHOR By HAROLD WILSON B01YBR IB.ffh.B. ProQuest Number: 13849841 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13849841 Published by ProQuest LLC(2019). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 -CONTENTS SECTION 1. Introduction. SECTION 2. General Remarks. Definitions of General Interest. Present Views on Etiology. Pathology and Morbid Anatomy. Brief Historical Survey. SECTION 3. The Present Position. Prevalence. Clinical Manifestations. Prognosis. SECTION 4. Prevalence in Bolton. Summary of Cases. Symptomatology and Case Histories Prognosis. Treatment. SECTION 5. Conclusions. Bibliography. SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION. I think it can truthfully be said that the most interest ing problems in Medioine are those that are most baffling. Some years ago Ralph M a j o r ^ wrote these words, ”If our knowledge of the etiology of arterial hypertension is shrouded in a oertain haze, our knowledge of an effective therapy in this disease is enveloped in a dense fog.n A study of some of the vast literature on this subject does not greatly clarify the obscurity. -

DISEASES of ARTERIES ARTERIOSCLEROSIS (“Hardening of the Arteries”): General Term Reflecting Arterial Wall Thickening and Loss of Elasticity

DISEASES OF ARTERIES ARTERIOSCLEROSIS (“hardening of the arteries”): general term reflecting arterial wall thickening and loss of elasticity 3 patterns •Atherosclerosis: involves the the aorta and the large arteries •Mönckeberg sclerosis: calcific deposits in the media of middle-sized arteries in persons >age 50 •Arteriolosclerosis: involves the small arteries and arterioles in association with hypertension or diabetes ATHEROSCLEROSIS Multifactorial, slowly progressive chronic degenerative-inflammatory disease of the aorta and the large arteries, such as • coronary arteries • circle of Willis • popliteal and tibial arteries Significance: > 50% of all death is attributed to atherosclerosis in well-developed countries Morphology Gross • Atheromatous plaque (pathognomic) - raised white-yellow lesion in the intima, protruding into the lumen • Large plaques in the aorta (> 2 cm) contain a yellow, grumous debris (”atheroma” - Greek word for gruel) Atheromatous plaque in the middle cerebral artery: raised white-yellow lesion in the intima, protruding into the lumen (formol-fixed brain) Aorta: the plaques contain a yellow, grumous debris (arrow) Structure of atheroma on LM • Intimal lesion • Central lipid core • Fibrous ”cap” subendothelially Central lipid core composed of lipids, cholesterol clefts, necrotic debris + calcium-salts, surrounded by foamy macrophages, T-lymphocytes, fibroblasts, small capillaries, and collagens and proteoglycans Types of plaques • Vulnerable plaques have large atheromatous cores, increased inflammatory cell content and thin fibrous caps high risk of rupture thrombosis • Stable plaques have minimal atheromatous cores and inflammation and thick fibrous caps 70% stenosis (critical stenosis) chronic ischemia distally Vulnerable plaque in the coronary artery Inflammatory infiltrates and capillaries around the lipid core. Lumen Intima Media Pathogenesis Response to chronic endocardial injury hypothesis • Cholesterol can’t dissolve in the blood. -

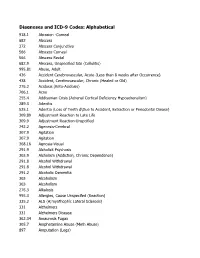

DSM III and ICD 9 Codes 11-2004

Diagnoses and ICD-9 Codes: Alphabetical 918.1 Abrasion -Corneal 682 Abscess 372 Abscess Conjunctiva 566 Abscess Corneal 566 Abscess Rectal 682.9 Abscess, Unspecified Site (Cellulitis) 995.81 Abuse, Adult 436 Accident Cerebrovascular, Acute (Less than 8 weeks after Occurrence) 438 Accident, Cerebrovascular, Chronic (Healed or Old) 276.2 Acidosis (Keto-Acidosis) 706.1 Acne 255.4 Addisonian Crisis (Adrenal Cortical Deficiency Hypoadrenalism) 289.3 Adenitis 525.1 Adentia (Loss of Teeth d\Due to Accident, Extraction or Periodontal Diease) 309.89 Adjustment Reaction to Late Life 309.9 Adjustment Reaction-Unspcified 742.2 Agenesis-Cerebral 307.9 Agitation 307.9 Agitation 368.16 Agnosia-Visual 291.9 Alcholick Psychosis 303.9 Alcholism (Addiction, Chronic Dependence) 291.8 Alcohol Withdrawal 291.8 Alcohol Withdrawal 291.2 Alcoholic Dementia 303 Alcoholism 303 Alcoholism 276.3 Alkalosis 995.3 Allergies, Cause Unspecifed (Reaction) 335.2 ALS (A;myothophic Lateral Sclerosis) 331 Alzheimers 331 Alzheimers Disease 362.34 Amaurosis Fugax 305.7 Amphetamine Abuse (Meth Abuse) 897 Amputation (Legs) 736.89 Amputation, Leg, Status Post (Above Knee, Below Knee) 736.9 Amputee, Site Unspecified (Acquired Deformity) 285.9 Anemia 284.9 Anemia Aplastic (Hypoplastic Bone Morrow) 280 Anemia Due to loss of Blood 281 Anemia Pernicious 280.9 Anemia, Iron Deficiency, Unspecified 285.9 Anemia, Unspecified (Normocytic, Not due to blood loss) 281.9 Anemia, Unspecified Deficiency (Macrocytic, Nutritional 441.5 Aneurysm Aortic, Ruptured 441.1 Aneurysm, Abdominal 441.3 Aneurysm, -

HYPERTENSION-I by ROBERT PLATE, M.D., M.Sc., F.R.C.P

BRITISH APRIL 22, 1950 HYPERTENSION MEDICAL JOURNAL 951 REFRESHER COURSE FOR GENERAL PRACTITIONERS HYPERTENSION-I BY ROBERT PLATE, M.D., M.Sc., F.R.C.P. Professor of Medicine, University of Manchester Hypertension is a syndrome and not a disease. A large tension in that they developed arteriolar necrosis in various number of cases with high blood pressure fall into the organs, though not, however, in the kidneys, because by the group which is known as primary or essential hypertension. very nature of the experiment the renal arterioles were This means that no pre-existing disease which might have protected from the effects of the high blood pressure. If caused the hypertension can be discovered. In other words, the renal artery of only one kidney was constricted, as Wakerlin (1949) has said, "'Essential hypertension' is hypertension was usually more transient and less severe, a designation born of ignorance and is equivalent to 'fever and if the affected kidney was removed the blood pressure of unknown cause."' Although we are ignorant of the returned to normal. cause of esgential hypertension I believe that it is much Wilson and Byrom (1939) found that severe hypertensiorn more than a merely negative diagnosis, and that it will of the malignant type could be produced in rats by con- turn out to be a definite entity with a recognizable patho- striction of only one renal artery, in which case the patho- genesis. A family history of hypertensive disease is present logical changes of malignant hypertension, with their in a high proportion of cases of essential hypertension. -

Dissecting Aneurysm of the Aorta

Cleveland Clinic Quarterly Volume 23 OCTOBER 1956 No. 4 DISSECTING ANEURYSM OF THE AORTA A Review ARTHUR L. SCHERBEL, M.D., Division of Medicine JOHN B. HAZARD, M.D., Department of Pathology and VICTOR G. DEWOLFE, M.D. Department of Cardiovascular Disease ISSECTING ANEURYSM OF THE AORTA is an intramural separation D of the aortic wall by circulating blood that has penetrated and extended into the media. The process may arrest at this stage and heal, progress im- mediately, or extend at some later date. As the dissecting aneurysm progresses, it may rupture through the adventitia into the pericardial, pleural, or abdominal cavities and may obstruct arteries arising from the aorta. It may rupture back into the lumen and form a double-barreled aorta, which may persist, or the aneurysm may be filled with clot and subsequently heal, obliterating the secondary channel. Etiology Although the specific cause of the disease is not known, the lesion that generally is accepted as being precedent to dissecting aneurysm of the aorta is 231 Downloaded from www.ccjm.org on September 26, 2021. For personal use only. All other uses require permission. SCHERBEL, HAZARD, AND DEWOLFE A Fig. 1. Changes in the media. (A) Medial degeneration (mucinous); hematoxylin, eosin and methylene blue stain, X80. (B) Marked loss of elastic tissue in a corresponding area; Verhoeff's stain, X80. 232 Cleveland Clinic Quarterly Downloaded from www.ccjm.org on September 26, 2021. For personal use only. All other uses require permission. DISSECTING ANEURYSM OF THE AORTA medial degeneration. This most often consists of mucoid changes in the media and focal loss of elastic tissue (Fig. -

Hypertension and the Kidney

8.10 Hypertension and the Kidney SPECTRUM OF CLINICAL RENAL INVOLVEMENT IN MALIGNANT HYPERTENSION Progressive subacute deterioration of renal function to end-stage renal disease Transient deterioration of renal function with initial blood pressure control Oliguric acute renal failure Established renal failure FIGURE 8-17 Malignant hypertension is a progressive systemic vasculopathy in which renal involvement is a relatively late finding. In this regard, patients with malignant hypertension can present with a spectrum of renal involvement ranging from normal renal function with minimal FIGURE 8-16 (see Color Plate) albuminuria to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) indistinguishable Micrograph of proliferative endarteritis in malignant hypertension from that seen in primary renal parenchymal disease. In patients (musculomucoid intimal hyperplasia). In malignant nephrosclerosis, initially exhibiting preserved renal function, in the absence of adequate the interlobular (cortical radial) arteries reveal characteristic lesions. blood pressure control, it is common to observe subacute deterio- These lesions are variously referred to as proliferative endarteritis, ration of renal function to ESRD over a period of weeks to months. endarteritis fibrosa, musculomucoid intimal hyperplasia, or the Transient deterioration of renal function with initial control of onionskin lesion. The typical finding is marked thickening of the blood pressure is a well-documented entity in patients initially intima that obstructs the vessel lumen. In severely affected vessels exhibiting mild to moderate renal impairment. Occasionally, the luminal diameter may be reduced to the caliber of a single ery- patients with malignant hypertension initially exhibit oliguric acute throcyte. Occasionally, complete obliteration of the lumen by a renal failure, necessitating initiation of dialysis within a few days of superimposed fibrin thrombus occurs. -

Incidence, Morbidity and Mortality of Patients with Achalasia in England: Findings from a Nationwide Hospital Database and 4 Million Population Based Data

Incidence, morbidity and mortality of patients with achalasia in England: findings from a nationwide hospital database and 4 million population based data Appendix A: International Classification of Disease codes for Achalasia (HES) K22 – Achalasia of cardia Appendix B: Read codes (The Health Improvement Network) Appendix B1: Achalasia codes Clinical code Description J100.00 Achalasia of cardia Appendix B2: Clinical codes used to identify Hypertension, Diabetes and lipid lowering drugs Diabetes Clinical code Description C10..00 Diabetes mellitus C100.00 Diabetes mellitus with no mention of complication C100000 Diabetes mellitus, juvenile type, no mention of complication C100011 Insulin dependent diabetes mellitus C100100 Diabetes mellitus, adult onset, no mention of complication C100111 Maturity onset diabetes C100112 Non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus C100z00 Diabetes mellitus NOS with no mention of complication C101.00 Diabetes mellitus with ketoacidosis C101000 Diabetes mellitus, juvenile type, with ketoacidosis C101100 Diabetes mellitus, adult onset, with ketoacidosis C101y00 Other specified diabetes mellitus with ketoacidosis C101z00 Diabetes mellitus NOS with ketoacidosis C102.00 Diabetes mellitus with hyperosmolar coma C102000 Diabetes mellitus, juvenile type, with hyperosmolar coma C102100 Diabetes mellitus, adult onset, with hyperosmolar coma C102z00 Diabetes mellitus NOS with hyperosmolar coma C103.00 Diabetes mellitus with ketoacidotic coma C103000 Diabetes mellitus, juvenile type, with ketoacidotic coma C103100 Diabetes -

Essential Hypertension*

BRmSw 30 October 1965 MEDICAL JOURNAL 1021 Br Med J: first published as 10.1136/bmj.2.5469.1021 on 30 October 1965. Downloaded from Hyperpiesis: High Blood-pressure without Evident Cause: Essential Hypertension* Sir GEORGE PICKERINGt M.D., D.SC., F.R.C.P., F.R.S. Brit. med.J_., 1965, 2, 1021-1026 Benign Hypertension that there is a third factor not in the coronary arteries and not the arterial pressure which contributes to hypertensive heart The benign phase of hypertension offers a great contrast to the disease. Could it possibly be related to advancing years, the malignant phase. The course is long and variable, with the disorder described by William Dock (1945) as presbycardia ? condition often remaining unchanged for years; thus, of As Fig. 12 shows, heart weight and arterial pressure are related Bechgaard's original 1,038 patients, 357 were alive after 20 quantitatively. Since, as Shirley Smith and Fowler (1955) and years (llechgaard et al., 1956). Bechgaard (unpublished) has Hamilton (1956) have shown, heart failure can be relieved and recently reported that 144 were alive after 26 to 32 years. prevented by lowering pressure, and since heart size decreases Uraemia does not occur; bilateral neuroretinopathy does not (Smirk, 1957), there is a strong case for supposing that elevation occur; cerebral oedema does not occur, or occurs only rarely; of arterial pressure is a causal factor in the cardiac changes. patients tend to die of heart failure, cerebral vascular disease, or intercurrent disease. Its nature is clearly different. The malignant phase is characterized by lesions which Cerebral Vascular Disease represent the limit of cardiovascular tolerance, fibrinoid arteriolar necrosis, retinal exudates representing focal vascular Cerebral vascular disease is still something of a morass. -

5. Upper Gastrointestinal Tract

5. UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT JOHANNA C. BENDELL, MD CHRISTOPHER WILLETT, MD Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC The upper gastrointestinal tract lies within the radiation field for most thoracic and abdominal cancers. Toxicity to the upper gastrointestinal tract often limits the radiation doses that can be given. Radiation therapy causes both acute and late effects. The acute effects of radiation include mucosal denudation, while late effects consist of fibrotic changes leading to decreased mobility and ischemia. Multifield and conformal radiation therapy, as well as patient positioning techniques, reduce the volume of normal tissue exposed to radiation and can decrease the potential toxicity. However, the treatment of radiation toxicity is mainly supportive. The increasing use of concurrent chemotherapy and radiation therapy has required enhanced awareness of potential effects and better methods to decrease toxicity, as this combination of treatments is associated with a higher rate of gastrointestinal toxicity. The first part of this chapter will review the pathologic changes of acute and chronic radiation effects, and the second part will discuss clinical effects, including radiation dosing and management of toxicities. A. BIOLOGY OF RADIATION EFFECTS A1. Esophagus Pathologic studies of animal models have been used to describe and characterize the effects of radiation to the esophagus. Pathologic changes include an acute thinning of the squamous epithelial layer with vacuolization and absence of mitoses, followed by areas of complete denudation and areas of increased basal cell proliferation. Chronic changes include focal coagulation necrosis of the muscularis mucosa and deep muscle as 112 Radiation Toxicity: A Practical Guide well as inflammatory changes around the ganglion cells of the mesenteric plexus in the deep wall.1,2 Physiologically, failure of the peristaltic wave and decreased relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter are seen. -

Hypertensive Emergencies

Introduction INTRODUCTION Hypertension is defined as sustained increase of systolic and diastolic blood pressure above the normal range for age ,sex and weight regardless of the primary causes accepted upper limits for ABP. Infants 70/45,early child hood 85/55, adolescents 100/75, adult 140/90 (Wongprasartsuk, 2003). Classification Several factors are taken into account in classifying an hypertensive condition: the evolution of the disease, the magnitude of the increase in blood pressure values, the etiology of the hypertensive state, and the absolute level of the total cardiovascular risk profile. The total risk profile appears to be the most comprehensive because, as suggested by the European Guidelines (Seedat. et al., 2002). A. Classification of Hypertension According to Disease Evolution The evolution of the hypertensive state allows classification of blood pressure elevation as two forms: malignant hypertension and benign hypertension. 1. Malignant Hypertension Malignant hypertension, which was first described as a separate disease entity about 90 years ago by Volhard and Fahr, is characterized by a very high blood pressure elevation (usually .200/120 mmHg) that is most often associated with an increase in plasma creatinine levels, renal dysfunction and failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and neurological manifestations of hypertensive encephalopathy (Seedat. et al., 2002). -1- Introduction The incidence of new cases of accelerated hypertension has decreased drastically in the past few years, primarily because earlier diagnosis and treatment of the disease prevents blood pressure increases in the vast majority of cases, as well as preventing the clinical manifestations and complications of such an elevation in pressure. The prognosis of malignant hypertension also has improved in the past few years because of the availability of new and effective antihypertensive compounds and the availability of renal dialysis and kidney transplantation (Seedat. -

Thrombosis (Lec#1)

Thrombosis (lec#1) * Pathogenesis (called Virchow's triad): Endothelial Injury ( Heart, Arteries), Stasis (abnormal blood flow),Blood Hypercoagulability . * Endothelial cells can be stimulated by direct injury or by various cytokines that are produced during inflammation. * Pathologic effect of vascular healing Excessive thickening of the intima luminal stenosis & blockage of vascular flow *Stasis: a major factor in venous thrombi. * Hypercoagulability A. Genetic (primary): - Mutations in the factor V gene and the prothrombin gene are the most common B. Acquired (secondary): - Multifactorial and is therefore more complicated * Morphology of thrombi : - Can develop anywhere in the CVS , focally attached to the underlying vascular surface. - Arterial or cardiac thrombi begin at sites of endothelial injury or turbulence; and are usually superimposed on an atherosclerotic plaque. - Venous thrombi occur at sites of stasis. Most commonly the veins of the lower extremities (90%). * lines of Zahn -Thrombi can have grossly (and microscopically) apparent laminations called lines of Zahn; these represent pale platelet and fibrin layers alternating with darker erythrocyte-rich layers. - Such lines are significant in that they represent thrombosis of flowing blood . - Postmortem blood clots are bland non-laminated clots (no lines of Zahn) . * Mural thrombi: thrombi occurring in heart chambers or in the aortic lumen. * Vegetations : Thrombi on heart valves - Types: 1- infectious (Bacterial or fungal blood-borne infections)(e.g. infective endocarditis,). 2-Non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis occur on sterile valves. * Venous thrombi: (veins of the legs) are most common a. Superficial: e.g. Saphenous veins , can cause local congestion, swelling, pain, and tenderness along the course of the involved vein, but they rarely embolize . -

Hypertension and the Kidney

8.16 Hypertension and the Kidney 2 MAP, mm Hg Heart rate, beats/min Cardiac index, L/min/m AHHF 200 200 120 5.0 NF 150 B B 90 mm Hg 100 NP 100 60 2.5 NP 50 Mean arterial 30 pressure, AHHF NF 0 0 0 0 P<0.005 P<0.005 NS NS NS Stroke work index, g m/m2 LVEDP, mm Hg LVEDV, mL/m2 40 B 150 60 200 L/min 9 30 NP 45 mm Hg 6 NP 20 75 30 100 B B NP 3 10 LVEDP, B NP 15 Cardiac output,Cardiac 0 0 0 0 0 P<0.005 NS P<0.005 P<0.025 NS P<0.005 NS Hemodynamic parameters at baseline (B) and during nitroprusside (NP) infusion A Baseline hemodynamics in acute hypertensive heart failure (AHHF) vs no failure (NF) B in both groups had electrocardiographic evidence of LV hypertrophy 60 AHHF: baseline caused by long-standing hypertension. AHHF: with nitroprusside A, Baseline hemodynamic measurements before treatment No failure: baseline 50 No failure: with nitroprusside revealed that the following measurements were the same in both groups: mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate, cardiac index, systemic vascular resistance, and stroke work index. Likewise, the 40 LV end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) was similar in both groups. In fact, the only hemodynamic difference between the groups was a mm Hg significant elevation of LV filling pressure (LVFP) (pulmonary capil- 30 lary wedge pressure) in the group with pulmonary edema. In acute LVFP, hypertensive heart failure the finding of elevated LV end-diastolic 20 pressures (LVEDPs), despite normal ejection fraction and cardiac index, implies the presence of isolated diastolic dysfunction.