Essential Hypertension*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High B1a0d Pressure and Its Treatment in General

HIGH B1A0D PRESSURE AND ITS TREATMENT IN GENERAL PRACTICE WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO A SERIES OF 100 CASES TREATED BY THE AUTHOR By HAROLD WILSON B01YBR IB.ffh.B. ProQuest Number: 13849841 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13849841 Published by ProQuest LLC(2019). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 -CONTENTS SECTION 1. Introduction. SECTION 2. General Remarks. Definitions of General Interest. Present Views on Etiology. Pathology and Morbid Anatomy. Brief Historical Survey. SECTION 3. The Present Position. Prevalence. Clinical Manifestations. Prognosis. SECTION 4. Prevalence in Bolton. Summary of Cases. Symptomatology and Case Histories Prognosis. Treatment. SECTION 5. Conclusions. Bibliography. SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION. I think it can truthfully be said that the most interest ing problems in Medioine are those that are most baffling. Some years ago Ralph M a j o r ^ wrote these words, ”If our knowledge of the etiology of arterial hypertension is shrouded in a oertain haze, our knowledge of an effective therapy in this disease is enveloped in a dense fog.n A study of some of the vast literature on this subject does not greatly clarify the obscurity. -

DISEASES of ARTERIES ARTERIOSCLEROSIS (“Hardening of the Arteries”): General Term Reflecting Arterial Wall Thickening and Loss of Elasticity

DISEASES OF ARTERIES ARTERIOSCLEROSIS (“hardening of the arteries”): general term reflecting arterial wall thickening and loss of elasticity 3 patterns •Atherosclerosis: involves the the aorta and the large arteries •Mönckeberg sclerosis: calcific deposits in the media of middle-sized arteries in persons >age 50 •Arteriolosclerosis: involves the small arteries and arterioles in association with hypertension or diabetes ATHEROSCLEROSIS Multifactorial, slowly progressive chronic degenerative-inflammatory disease of the aorta and the large arteries, such as • coronary arteries • circle of Willis • popliteal and tibial arteries Significance: > 50% of all death is attributed to atherosclerosis in well-developed countries Morphology Gross • Atheromatous plaque (pathognomic) - raised white-yellow lesion in the intima, protruding into the lumen • Large plaques in the aorta (> 2 cm) contain a yellow, grumous debris (”atheroma” - Greek word for gruel) Atheromatous plaque in the middle cerebral artery: raised white-yellow lesion in the intima, protruding into the lumen (formol-fixed brain) Aorta: the plaques contain a yellow, grumous debris (arrow) Structure of atheroma on LM • Intimal lesion • Central lipid core • Fibrous ”cap” subendothelially Central lipid core composed of lipids, cholesterol clefts, necrotic debris + calcium-salts, surrounded by foamy macrophages, T-lymphocytes, fibroblasts, small capillaries, and collagens and proteoglycans Types of plaques • Vulnerable plaques have large atheromatous cores, increased inflammatory cell content and thin fibrous caps high risk of rupture thrombosis • Stable plaques have minimal atheromatous cores and inflammation and thick fibrous caps 70% stenosis (critical stenosis) chronic ischemia distally Vulnerable plaque in the coronary artery Inflammatory infiltrates and capillaries around the lipid core. Lumen Intima Media Pathogenesis Response to chronic endocardial injury hypothesis • Cholesterol can’t dissolve in the blood. -

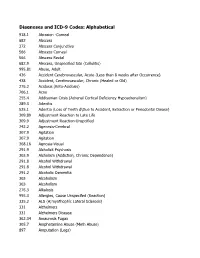

DSM III and ICD 9 Codes 11-2004

Diagnoses and ICD-9 Codes: Alphabetical 918.1 Abrasion -Corneal 682 Abscess 372 Abscess Conjunctiva 566 Abscess Corneal 566 Abscess Rectal 682.9 Abscess, Unspecified Site (Cellulitis) 995.81 Abuse, Adult 436 Accident Cerebrovascular, Acute (Less than 8 weeks after Occurrence) 438 Accident, Cerebrovascular, Chronic (Healed or Old) 276.2 Acidosis (Keto-Acidosis) 706.1 Acne 255.4 Addisonian Crisis (Adrenal Cortical Deficiency Hypoadrenalism) 289.3 Adenitis 525.1 Adentia (Loss of Teeth d\Due to Accident, Extraction or Periodontal Diease) 309.89 Adjustment Reaction to Late Life 309.9 Adjustment Reaction-Unspcified 742.2 Agenesis-Cerebral 307.9 Agitation 307.9 Agitation 368.16 Agnosia-Visual 291.9 Alcholick Psychosis 303.9 Alcholism (Addiction, Chronic Dependence) 291.8 Alcohol Withdrawal 291.8 Alcohol Withdrawal 291.2 Alcoholic Dementia 303 Alcoholism 303 Alcoholism 276.3 Alkalosis 995.3 Allergies, Cause Unspecifed (Reaction) 335.2 ALS (A;myothophic Lateral Sclerosis) 331 Alzheimers 331 Alzheimers Disease 362.34 Amaurosis Fugax 305.7 Amphetamine Abuse (Meth Abuse) 897 Amputation (Legs) 736.89 Amputation, Leg, Status Post (Above Knee, Below Knee) 736.9 Amputee, Site Unspecified (Acquired Deformity) 285.9 Anemia 284.9 Anemia Aplastic (Hypoplastic Bone Morrow) 280 Anemia Due to loss of Blood 281 Anemia Pernicious 280.9 Anemia, Iron Deficiency, Unspecified 285.9 Anemia, Unspecified (Normocytic, Not due to blood loss) 281.9 Anemia, Unspecified Deficiency (Macrocytic, Nutritional 441.5 Aneurysm Aortic, Ruptured 441.1 Aneurysm, Abdominal 441.3 Aneurysm, -

Orthostatic Hypotension in a Cohort of Hypertensive Patients Referring to a Hypertension Clinic

Journal of Human Hypertension (2015) 29, 599–603 © 2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0950-9240/15 www.nature.com/jhh ORIGINAL ARTICLE Orthostatic hypotension in a cohort of hypertensive patients referring to a hypertension clinic C Di Stefano, V Milazzo, S Totaro, G Sobrero, A Ravera, A Milan, S Maule and F Veglio The prevalence of orthostatic hypotension (OH) in hypertensive patients ranges from 3 to 26%. Drugs are a common cause of non-neurogenic OH. In the present study, we retrospectively evaluated the medical records of 9242 patients with essential hypertension referred to our Hypertension Unit. We analysed data on supine and standing blood pressure values, age, sex, severity of hypertension and therapeutic associations of drugs, commonly used in the treatment of hypertension. OH was present in 957 patients (10.4%). Drug combinations including α-blockers, centrally acting drugs, non-dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers and diuretics were associated with OH. These pharmacological associations must be administered with caution, especially in hypertensive patients at high risk of OH (elderly or with severe and uncontrolled hypertension). Angiotensin-receptor blocker (ARB) seems to be not related with OH and may have a potential protective effect on the development of OH. Journal of Human Hypertension (2015) 29, 599–603; doi:10.1038/jhh.2014.130; published online 29 January 2015 INTRODUCTION stabilization, and then at 1 and 3 min after standing. The average of the Orthostatic hypotension (OH) is defined as the reduction in blood last two SBP and DBP values measured in the supine position and the pressure (BP) of at least 20 mmHg systolic and/or 10 mm Hg lowest value during standing were considered. -

HYPERTENSION-I by ROBERT PLATE, M.D., M.Sc., F.R.C.P

BRITISH APRIL 22, 1950 HYPERTENSION MEDICAL JOURNAL 951 REFRESHER COURSE FOR GENERAL PRACTITIONERS HYPERTENSION-I BY ROBERT PLATE, M.D., M.Sc., F.R.C.P. Professor of Medicine, University of Manchester Hypertension is a syndrome and not a disease. A large tension in that they developed arteriolar necrosis in various number of cases with high blood pressure fall into the organs, though not, however, in the kidneys, because by the group which is known as primary or essential hypertension. very nature of the experiment the renal arterioles were This means that no pre-existing disease which might have protected from the effects of the high blood pressure. If caused the hypertension can be discovered. In other words, the renal artery of only one kidney was constricted, as Wakerlin (1949) has said, "'Essential hypertension' is hypertension was usually more transient and less severe, a designation born of ignorance and is equivalent to 'fever and if the affected kidney was removed the blood pressure of unknown cause."' Although we are ignorant of the returned to normal. cause of esgential hypertension I believe that it is much Wilson and Byrom (1939) found that severe hypertensiorn more than a merely negative diagnosis, and that it will of the malignant type could be produced in rats by con- turn out to be a definite entity with a recognizable patho- striction of only one renal artery, in which case the patho- genesis. A family history of hypertensive disease is present logical changes of malignant hypertension, with their in a high proportion of cases of essential hypertension. -

Hypertension and the Prothrombotic State

Journal of Human Hypertension (2000) 14, 687–690 2000 Macmillan Publishers Ltd All rights reserved 0950-9240/00 $15.00 www.nature.com/jhh REVIEW ARTICLE Hypertension and the prothrombotic state GYH Lip Haemostasis Thrombosis and Vascular Biology Unit, University Department of Medicine, City Hospital, Birmingham, UK The basic underlying pathophysiological processes related to conventional risk factors, target organ dam- underlying the major complications of hypertension age, complications and long-term prognosis, as well as (that is, heart attacks and strokes) are thrombogenesis different antihypertensive treatments. Further work is and atherogenesis. Indeed, despite the blood vessels needed to examine the mechanisms leading to this being exposed to high pressures in hypertension, the phenomenon, the potential prognostic and treatment complications of hypertension are paradoxically throm- implications, and the possible value of measuring these botic in nature rather than haemorrhagic. The evidence parameters in routine clinical practice. suggests that hypertension appears to confer a Journal of Human Hypertension (2000) 14, 687–690 prothrombotic or hypercoagulable state, which can be Keywords: hypercoagulable; prothrombotic; coagulation; haemorheology; prognosis Introduction Indeed, patients with hypertension are well-recog- nised to demonstrate abnormalities of each of these Hypertension is well-recognised to be an important 1 components of Virchow’s triad, leading to a contributor to heart attacks and stroke. Further- prothrombotic or hypercoagulable state.4 Further- more, effective antihypertensive therapy reduces more, the processes of thrombogenesis and athero- strokes by 30–40%, and coronary artery disease by 2 genesis are intimately related, and many of the basic approximately 25%. Nevertheless the basic under- concepts thrombogenesis can be applied to athero- lying pathophysiological processes underlying both genesis. -

Major Clinical Considerations for Secondary Hypertension And

& Experim l e ca n i t in a l l C Journal of Clinical and Experimental C f a o r d l i a o Thevenard et al., J Clin Exp Cardiolog 2018, 9:11 n l o r g u y o Cardiology DOI: 10.4172/2155-9880.1000616 J ISSN: 2155-9880 Review Article Open Access Major Clinical Considerations for Secondary Hypertension and Treatment Challenges: Systematic Review Gabriela Thevenard1, Nathalia Bordin Dal-Prá1 and Idiberto José Zotarelli Filho2* 1Santa Casa de Misericordia Hospital, São Paulo, Brazil 2Department of scientific production, Street Ipiranga, São José do Rio Preto, São Paulo, Brazil *Corresponding author: Idiberto José Zotarelli Filho, Department of scientific production, Street Ipiranga, São José do Rio Preto, São Paulo, Brazil, Tel: +5517981666537; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: October 30, 2018; Accepted date: November 23, 2018; Published date: November 30, 2018 Copyright: ©2018 Thevenard G, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Introduction: In this context, secondary arterial hypertension (SH) is defined as an increase in systemic arterial pressure (SAP) due to an identifiable cause. Only 5 to 10% of patients suffering from hypertension have a secondary form, while the vast majorities have essential hypertension. Objective: This study aimed to describe, through a systematic review, the main considerations on secondary hypertension, presenting its clinical data and main causes, as well as presenting the types of treatments according to the literary results. -

Dissecting Aneurysm of the Aorta

Cleveland Clinic Quarterly Volume 23 OCTOBER 1956 No. 4 DISSECTING ANEURYSM OF THE AORTA A Review ARTHUR L. SCHERBEL, M.D., Division of Medicine JOHN B. HAZARD, M.D., Department of Pathology and VICTOR G. DEWOLFE, M.D. Department of Cardiovascular Disease ISSECTING ANEURYSM OF THE AORTA is an intramural separation D of the aortic wall by circulating blood that has penetrated and extended into the media. The process may arrest at this stage and heal, progress im- mediately, or extend at some later date. As the dissecting aneurysm progresses, it may rupture through the adventitia into the pericardial, pleural, or abdominal cavities and may obstruct arteries arising from the aorta. It may rupture back into the lumen and form a double-barreled aorta, which may persist, or the aneurysm may be filled with clot and subsequently heal, obliterating the secondary channel. Etiology Although the specific cause of the disease is not known, the lesion that generally is accepted as being precedent to dissecting aneurysm of the aorta is 231 Downloaded from www.ccjm.org on September 26, 2021. For personal use only. All other uses require permission. SCHERBEL, HAZARD, AND DEWOLFE A Fig. 1. Changes in the media. (A) Medial degeneration (mucinous); hematoxylin, eosin and methylene blue stain, X80. (B) Marked loss of elastic tissue in a corresponding area; Verhoeff's stain, X80. 232 Cleveland Clinic Quarterly Downloaded from www.ccjm.org on September 26, 2021. For personal use only. All other uses require permission. DISSECTING ANEURYSM OF THE AORTA medial degeneration. This most often consists of mucoid changes in the media and focal loss of elastic tissue (Fig. -

How to Document and Code for Hypertensive Diseases in ICD-10 THIS INSTALLMENT in FPM’S ICD-10 SERIES EXPLAINS the GUIDELINES for CODING HYPERTENSION

How to Document and Code for Hypertensive Diseases in ICD-10 THIS INSTALLMENT IN FPM’S ICD-10 SERIES EXPLAINS THE GUIDELINES FOR CODING HYPERTENSION. Kenneth D. Beckman, MD, MBA, CPE, CPC ecause ICD-10 can be a distressing topic, let’s start or kidney disease. That code is I10, Essential (primary) with some good news: Hypertension has a limited hypertension. number of ICD-10 codes – only nine codes for pri- As in ICD-9, this code includes “high blood pressure” mary hypertension and five codes for secondary but does not include elevated blood pressure without a B hypertension. This makes the task of coding hypertension diagnosis of hypertension (that would be ICD-10 code relatively simple – well, at least compared to some of the R03.0). If a patient has progressed from elevated blood other ICD-10 complexities. pressure to a formal diagnosis of hypertension, a good Another positive change in ICD-10 is that the new documentation practice would be to include the reason for code set drops the previous reference to benign and progressing the formal diagnosis. Similarly, a single mildly malignant hypertension. As physicians, we are well aware elevated blood pressure reading should be coded with the that hypertension is never truly “benign,” and the removal R03.0 until the formal diagnosis is established. of this antiquated term is a welcome improvement in the Although various sources define hypertension slightly lexicon of diseases. differently, the provider should document elevated systolic But, of course, nothing is easy in ICD-10, and there are pressure above 140 or diastolic pressure above 90 with at several things you need to be aware of before we dig into least two readings on separate office visits. -

Hypertension and the Kidney

8.10 Hypertension and the Kidney SPECTRUM OF CLINICAL RENAL INVOLVEMENT IN MALIGNANT HYPERTENSION Progressive subacute deterioration of renal function to end-stage renal disease Transient deterioration of renal function with initial blood pressure control Oliguric acute renal failure Established renal failure FIGURE 8-17 Malignant hypertension is a progressive systemic vasculopathy in which renal involvement is a relatively late finding. In this regard, patients with malignant hypertension can present with a spectrum of renal involvement ranging from normal renal function with minimal FIGURE 8-16 (see Color Plate) albuminuria to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) indistinguishable Micrograph of proliferative endarteritis in malignant hypertension from that seen in primary renal parenchymal disease. In patients (musculomucoid intimal hyperplasia). In malignant nephrosclerosis, initially exhibiting preserved renal function, in the absence of adequate the interlobular (cortical radial) arteries reveal characteristic lesions. blood pressure control, it is common to observe subacute deterio- These lesions are variously referred to as proliferative endarteritis, ration of renal function to ESRD over a period of weeks to months. endarteritis fibrosa, musculomucoid intimal hyperplasia, or the Transient deterioration of renal function with initial control of onionskin lesion. The typical finding is marked thickening of the blood pressure is a well-documented entity in patients initially intima that obstructs the vessel lumen. In severely affected vessels exhibiting mild to moderate renal impairment. Occasionally, the luminal diameter may be reduced to the caliber of a single ery- patients with malignant hypertension initially exhibit oliguric acute throcyte. Occasionally, complete obliteration of the lumen by a renal failure, necessitating initiation of dialysis within a few days of superimposed fibrin thrombus occurs. -

Hypertensive Emergencies Are Associated with Elevated Markers of Inflammation, Coagulation, Platelet Activation and fibrinolysis

Journal of Human Hypertension (2013) 27, 368–373 & 2013 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0950-9240/13 www.nature.com/jhh ORIGINAL ARTICLE Hypertensive emergencies are associated with elevated markers of inflammation, coagulation, platelet activation and fibrinolysis U Derhaschnig1,2, C Testori2, E Riedmueller2, S Aschauer1, M Wolzt1 and B Jilma1 Data from in vitro and animal experiments suggest that progressive endothelial damage with subsequent activation of coagulation and inflammation have a key role in hypertensive crisis. However, clinical investigations are scarce. We hypothesized that hypertensive emergencies are associated with enhanced inflammation, endothelial- and coagulation activation. Thus, we enrolled 60 patients admitted to an emergency department in a prospective, cross-sectional study. We compared markers of coagulation, fibrinolysis (prothrombin fragment F1 þ 2, plasmin–antiplasmin complexes, plasmin-activator inhibitor, tissue plasminogen activator), platelet- and endothelial activation and inflammation (P-selectin, C-reactive protein, leukocyte counts, fibrinogen, soluble vascular adhesion molecule-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, myeloperoxidase and asymmetric dimethylarginine) between hypertensive emergencies, urgencies and normotensive patients. In hypertensive emergencies, markers of inflammation and endothelial activation were significantly higher as compared with urgencies and controls (Po0.05). Likewise, plasmin–antiplasmin complexes were 75% higher in emergencies as compared with urgencies (Po0.001), as were tissue plasminogen-activator levels (B30%; Po0.05) and sP-selectin (B40%; Po0.05). In contrast, similar levels of all parameters were found between urgencies and controls. We consistently observed elevated markers of thrombogenesis, fibrinolysis and inflammation in hypertensive emergencies as compared with urgencies. Further studies will be needed to clarify if these alterations are cause or consequence of target organ damage. -

Quality ID #236 (NQF 0018): Controlling High Blood Pressure

Quality ID #236 (NQF 0018): Controlling High Blood Pressure – National Quality Strategy Domain: Effective Clinical Care – Meaningful Measure Area: Management of Chronic Conditions 2019 COLLECTION TYPE: MIPS CLINICAL QUALITY MEASURES (CQMS) MEASURE TYPE: Intermediate Outcome – High Priority DESCRIPTION: Percentage of patients 18 - 85 years of age who had a diagnosis of hypertension and whose blood pressure was adequately controlled (< 140/90 mmHg) during the measurement period INSTRUCTIONS: This measure is to be submitted a minimum of once per performance period for patients with hypertension seen during the performance period. The performance period for this measure is 12 months. The most recent quality code submitted will be used for performance calculation. This measure may be submitted by Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) eligible clinicians who perform the quality actions described in the measure based on the services provided and the measure-specific denominator coding. NOTE: In reference to the numerator element, only blood pressure readings performed by a clinician in the provider office are acceptable for numerator compliance with this measure. Do not include blood pressure readings that meet the following criteria: • Blood pressure readings from the patient's home (including readings directly from monitoring devices). • Taken on the same day as a diagnostic test or diagnostic or therapeutic procedure that requires a change in diet or change in medication on or one day before the day of the test or procedure, with the exception of fasting blood tests. If no blood pressure is recorded during the measurement period, the patient’s blood pressure is assumed “not controlled”. Measure Submission Type: Measure data may be submitted by individual MIPS eligible clinicians, groups, or third party intermediaries.