Railroad Safety-U.S.-Canadian Comparison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transportation on the Minneapolis Riverfront

RAPIDS, REINS, RAILS: TRANSPORTATION ON THE MINNEAPOLIS RIVERFRONT Mississippi River near Stone Arch Bridge, July 1, 1925 Minnesota Historical Society Collections Prepared by Prepared for The Saint Anthony Falls Marjorie Pearson, Ph.D. Heritage Board Principal Investigator Minnesota Historical Society Penny A. Petersen 704 South Second Street Researcher Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 Hess, Roise and Company 100 North First Street Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 May 2009 612-338-1987 Table of Contents PROJECT BACKGROUND AND METHODOLOGY ................................................................................. 1 RAPID, REINS, RAILS: A SUMMARY OF RIVERFRONT TRANSPORTATION ......................................... 3 THE RAPIDS: WATER TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS .............................................. 8 THE REINS: ANIMAL-POWERED TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ............................ 25 THE RAILS: RAILROADS BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ..................................................................... 42 The Early Period of Railroads—1850 to 1880 ......................................................................... 42 The First Railroad: the Saint Paul and Pacific ...................................................................... 44 Minnesota Central, later the Chicago, Milwaukee and Saint Paul Railroad (CM and StP), also called The Milwaukee Road .......................................................................................... 55 Minneapolis and Saint Louis Railway ................................................................................. -

Chungkai Hospital Camp | Part One: Mid-October 1942 to Mid-May 1944 " Sears Eldredge Macalester College

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Book Chapters Captive Audiences/Captive Performers 2014 Chapter 6a. "Chungkai Showcase": Chungkai Hospital Camp | Part One: Mid-October 1942 to Mid-May 1944 " Sears Eldredge Macalester College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/thdabooks Recommended Citation Eldredge, Sears, "Chapter 6a. "Chungkai Showcase": Chungkai Hospital Camp | Part One: Mid-October 1942 to Mid-May 1944 "" (2014). Book Chapters. Book 16. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/thdabooks/16 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Captive Audiences/Captive Performers at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 184 Chapter 6: “Chungkai Showcase” Chungkai Hospital Camp Part One: Mid-October 1942 to to Mid-May 1944 FIGURE 6.1. CHUNGKAI THEATRE LOGO. HUIB VAN LAAR. IMAGE COPYRIGHT MUSEON, THE HAGUE, NETHERLANDS. Though POWs in other camps in Thailand produced amazing musical and theatrical offerings for their audiences, it was the performers in Chungkai who, arguably, produced the most diverse, elaborate, and astonishing entertainment on the Thailand-Burma railway. Between Christmas 1943 and May 1945 they presented over sixty-five musical or theatrical productions. As there is more detailed information about the administration, production, and reception of the entertainment at Chungkai than at any other camp on the railway, the focus in this chapter will be on those productions and personalities that stand out in some significant way artistically, technically, or politically. To cover this material adequately, the chapter will be divided into two parts: Part One will cover the period from mid-October 1942 to mid-May 1944; Part Two, from mid-May 1944 to July 1945. -

Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the National Archives

REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 116 Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the national archives 1 Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the National Archives REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 116 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC Compiled by Peter F. Brauer 2010 United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Records relating to railroads in the cartographic section of the National Archives / compiled by Peter F. Brauer.— Washington, DC : National Archives and Records Administration, 2010. p. ; cm.— (Reference information paper ; no 116) includes index. 1. United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Cartographic and Architectural Branch — Catalogs. 2. Railroads — United States — Armed Forces — History —Sources. 3. United States — Maps — Bibliography — Catalogs. I. Brauer, Peter F. II. Title. Cover: A section of a topographic quadrangle map produced by the U.S. Geological Survey showing the Union Pacific Railroad’s Bailey Yard in North Platte, Nebraska, 1983. The Bailey Yard is the largest railroad classification yard in the world. Maps like this one are useful in identifying the locations and names of railroads throughout the United States from the late 19th into the 21st century. (Topographic Quadrangle Maps—1:24,000, NE-North Platte West, 1983, Record Group 57) table of contents Preface vii PART I INTRODUCTION ix Origins of Railroad Records ix Selection Criteria xii Using This Guide xiii Researching the Records xiii Guides to Records xiv Related -

Quarterly Portfolio Disclosure

Schroders 29/05/2020 ASX Limited Schroders Investment Management Australia Limited ASX Market Announcements Office ABN:22 000 443 274 Exchange Centre Australian Financial Services Licence: 226473 20 Bridge Street Sydney NSW 2000 Level 20 Angel Place 123 Pitt Street Sydney NSW 2000 P: 1300 180 103 E: [email protected] W: www.schroders.com.au/GROW Schroder Real Return Fund (Managed Fund) Quarterly holdings disclosure for quarter ending 31 March 2020 Holdings on a full look through basis as at 31 March 2020 Weight Asset Name (%) 1&1 DRILLISCH AG 0.000% 1011778 BC / NEW RED FIN 4.25 15-MAY-2024 144a (SECURED) 0.002% 1011778 BC UNLIMITED LIABILITY CO 3.875 15-JAN-2028 144a (SECURED) 0.001% 1011778 BC UNLIMITED LIABILITY CO 4.375 15-JAN-2028 144a (SECURED) 0.001% 1011778 BC UNLIMITED LIABILITY CO 5.0 15-OCT-2025 144a (SECURED) 0.004% 1MDB GLOBAL INVESTMENTS LTD 4.4 09-MAR-2023 Reg-S (SENIOR) 0.011% 1ST SOURCE CORP 0.000% 21VIANET GROUP ADR REPRESENTING SI ADR 0.000% 2I RETE GAS SPA 1.608 31-OCT-2027 Reg-S (SENIOR) 0.001% 2I RETE GAS SPA 2.195 11-SEP-2025 Reg-S (SENIOR) 0.001% 2U INC 0.000% 360 SECURITY TECHNOLOGY INC A A 0.000% 360 SECURITY TECHNOLOGY INC A A 0.000% 361 DEGREES INTERNATIONAL LTD 0.000% 3D SYSTEMS CORP 0.000% 3I GROUP PLC 0.002% 3M 0.020% 3M CO 1.625 19-SEP-2021 (SENIOR) 0.001% 3M CO 1.75 14-FEB-2023 (SENIOR) 0.001% 3M CO 2.0 14-FEB-2025 (SENIOR) 0.001% 3M CO 2.0 26-JUN-2022 (SENIOR) 0.001% 3M CO 2.25 15-MAR-2023 (SENIOR) 0.001% 3M CO 2.75 01-MAR-2022 (SENIOR) 0.001% 3M CO 3.25 14-FEB-2024 (SENIOR) 0.002% -

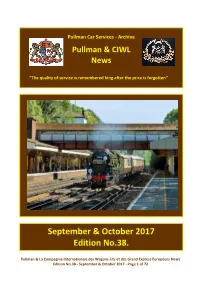

Pullman Car Services - Archive

Pullman Car Services - Archive Pullman & CIWL News “The quality of service is remembered long after the price is forgotten” September & October 2017 Edition No.38. Pullman & La Compagnie Internationale des Wagons -Lits et des Grand Express Européens News Edition No.38 - September & October 2017 - Page 1 of 72 COVER PHOTOGRAPH: Paul Blowfield - Communications & Marketing Officer, MNLPS - www.clan-line.org July 5th, 2017, marking 50 years to the day that the last steam hauled ‘Bournemouth Belle’ ran. The Merchant Navy Locomotive Preservation Society No.35028 Clan Line with ‘The Bournemouth Belle’ (Belmond British Pullman Cars) passing through Weybridge Station on the ‘Down’ main line. From the Coupé. Welcome aboard your bi-monthly newsletter. I take this opportunity to thank those readers who have kindly taken time to forward contributions in the form of articles and photographs for this edition. I remain dependent on contributions of news, articles (Word) and photographs (jpg) formats in all aspects of Pullman and CIWL operations both past, present, future and related aspects within model railways. All I ask of you for the time I spend in producing your newsletter, is for you to forward on by either E-mail or printing a copy, to any one you believe would be interested in reading your newsletter. Publication of the newsletter being scheduled on or about the 1st of January, March, May, July, September and November. The next edition editorial deadline date of Saturday October 28th, with the scheduled publication date of Wednesday November 1st, 2017. The views and articles within this publication are not necessarily those of the editor. -

Research on Railroad Ballast Specification and Evaluation

Transportation Research Record 1006 l Research on Railroad Ballast Specification and Evaluation GERALD P. RAYMOND ABSTRACT Research leading to recommended procedures for ballast selection and grading are presented. The ballast selection procedure is also presented and offers a sequential screening process to eliminate undesirable materials. The procedure classifies the surviving ballasts in terms of annual gross tonnage based on 30 tonne (33 ton) axle loading and American Railway Engineering Association grad ing No. 4. The effect of grading variation and its effect on track performance is also presented. From 1970 to 1978 Transport Canada Research and De color, and chemical composition. From a ballast per velopment Centre, Canadian National Railway Company, formance viewpoint, mineral hardness, generally and Canadian Pacific Limited cosponsored a research based on Mohs hardness scale, is of considerable im program at Queen's University through the Canadian portance. Institute of Guided Ground Transport to investigate Particular geological processes give rise to the stresses and deformations in the railway track three rock types, igneous, sedimentary, and meta structure and the support under dynamic and static morphic. Rock specimens may be used to classify the load systems. The findings and recommendations re rock type and also to provide information about the garding the specification for evaluating processed geological history of the area where it was located. rock , slag, and gravel railway ballast sources are This information is valuable to the ballast selec summarized in this paper. Comments are included tion process. about the new Canadian Pacific Rail ballast specif i cation, which was partially based on the findings presented by Raymond et al. -

Comparison of Canadian and United States Rail Economic Regulations

www.cpcs.ca FINAL REPORT Comparison of Canadian and United States Rail Economic Regulations Prepared for: The Railway Association of Canada Prepared by: CPCS CPCS Ref: 13381 January 20, 2015 FINAL REPORT | Comparison of Canadian and U.S. Rail Economic Regulations CPCS Ref: 13381 Table of Contents Acronyms / Abbreviations ............................................................................................................. 1 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... 2 1 Purpose of the Report .................................................................................................................. 2 2 Scope of Rail Economic Regulation .............................................................................................. 2 3 National Transportation Policy Statements ................................................................................. 3 4 Market Entry and Exit ................................................................................................................... 4 5 Level of Services ........................................................................................................................... 5 6 Pricing of Services ......................................................................................................................... 5 7 Competitive Access Provisions ..................................................................................................... 7 8 Mediation and -

Union Depot Tower Interlocking Plant

Union Depot Tower Union Depot Tower (U.D. Tower) was completed in 1914 as part of a municipal project to improve rail transportation through Joliet, which included track elevation of all four railroad lines that went through downtown Joliet and the construction of a new passenger station to consolidate the four existing passenger stations into one. A result of this overall project was the above-grade intersection of 4 north-south lines with 4 east-west lines. The crossing of these rail lines required sixteen track diamonds. A diamond is a fixed intersection between two tracks. The purpose of UD Tower was to ensure and coordinate the safe and timely movement of trains through this critical intersection of east-west and north-south rail travel. UD Tower housed the mechanisms for controlling the various rail switches at the intersection, also known as an interlocking plant. Interlocking Plant Interlocking plants consisted of the signaling appliances and tracks at the intersections of major rail lines that required a method of control to prevent collisions and provide for the efficient movement of trains. Most interlocking plants had elevated structures that housed mechanisms for controlling the various rail switches at the intersection. Union Depot Tower is such an elevated structure. Source: Museum of the American Railroad Frisco Texas CSX Train 1513 moves east through the interlocking. July 25, 1997. Photo courtesy of Tim Frey Ownership of Union Depot Tower Upon the completion of Union Depot Tower in 1914, U.D. Tower was owned and operated by the four rail companies with lines that came through downtown Joliet. -

The Myth of the Standard Gauge

The Myth of the Standard Guage: Rail Guage Choice in Australia, 1850-1901 Author Mills, John Ayres Published 2007 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Griffith Business School DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/426 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366364 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au THE MYTH OF THE STANDARD GAUGE: RAIL GAUGE CHOICE IN AUSTRALIA, 1850 – 1901 JOHN AYRES MILLS B.A.(Syd.), M.Prof.Econ. (U.Qld.) DEPARTMENT OF ACCOUNTING, FINANCE & ECONOMICS GRIFFITH BUSINESS SCHOOL GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2006 ii ABSTRACT This thesis describes the rail gauge decision-making processes of the Australian colonies in the period 1850 – 1901. Federation in 1901 delivered a national system of railways to Australia but not a national railway system. Thus the so-called “standard” gauge of 4ft. 8½in. had not become the standard in Australia at Federation in 1901, and has still not. It was found that previous studies did not examine cause and effect in the making of rail gauge choices. This study has done so, and found that rail gauge choice decisions in the period 1850 to 1901 were not merely one-off events. Rather, those choices were part of a search over fifty years by government representatives seeking colonial identity/autonomy and/or platforms for election/re-election. Consistent with this interpretation of the history of rail gauge choice in the Australian colonies, no case was found where rail gauge choice was a function of the disciplined search for the best value-for-money option. -

Rail Plan 2005 - 2006

Kansas Department of Transportation Rail Plan 2005 - 2006 Kathleen Sebelius, Governor Debra L. Miller, Secretary of Transportation Kansas Department of Transportation Division of Planning and Development Bureau of Transportation Planning – Office of Rail Affairs Kansas Rail Plan Update 2005 - 2006 Kansas Department of Transportation Division of Planning and Development Bureau of Transportation Planning Office of Rail Affairs Dwight D. Eisenhower State Office Building 700 SW Harrison Street, Second Floor Tower Topeka, Kansas 66603-3754 Telephone: (785) 296-3841 Fax: (785) 296-0963 Debra L. Miller, Secretary of Transportation Terry Heidner, Division of Planning and Development Director Chris Herrick, Chief of Transportation Planning Bureau John Jay Rosacker, Assistant Chief Transportation Planning Bureau ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Prepared by CONTRIBUTORS Office of Rail Affairs Staff John W. Maddox, CPM, Rail Affairs Program Manager Darlene K. Osterhaus, Rail Affairs Research Analyst Edward Dawson, Rail Affairs Research Analyst Paul Ahlenius, P.E., Rail Affairs Engineer Bureau of Transportation Planning Staff John Jay Rosacker, Assistant Chief Transportation Planning Bureau Carl Gile, Decision Mapping Technician Specialist OFFICE OF RAIL AFFAIRS WEB SITE http://www.ksdot.org/burRail/Rail/default.asp Pictures provided by railroads or taken by Office of Rail Affairs staff Railroad data and statistics provided by railroads 1 Executive Summary The Kansas Rail Plan Update 2005 - 2006 has Transportation Act (49 U.S.C. 1654 et seg). Financial been prepared in accordance with requirements of the assistance in the form of Federal Rail Administration Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) U.S. Department (FRA) grants has been used to fund rehabilitation of Transportation (USDOT), as set forth in federal projects throughout Kansas. -

Title Subject Author Publ Abbr Date Price Format Size Binding Pages

Title Subject Author Publ abbr Date Price Cond Sub title Notes ISBN Number Qty Size Pages Format Binding 100 Jahre Berner-Oberland-Bahnen; EK-Special 18 SWISS,NG Muller,Jossi EKV 1990 $24.00 V 4 SC 164 exc Die Bahnen der Jungfrauregiongerman text EKS18 1 100 Trains, 100 Years, A Century of Locomotives andphotos Trains Winkowski, SullivanCastle 2005 $20.00 V 5 HC 167 exc 0-7858-1669-0 1 100 Years of Capital Traction trolleys King Taylor 1972 $75.00 V 4 HC The329 StoryExc of Streetcars in the Nations Capital 72-97549 1 100 Years of Steam Locomotives locos Lucas Simmons-Boardman1957 $50.00 V 4 HC 278 exc plans & photos 57-12355 1 125 Jahre Brennerbahn, Part 2 AUSTRIA Ditterich HMV 1993 $24.00 V 4 T 114 NEW Eisenbahn Journal germanSpecial text,3/93 color 3-922404-33-2 1 1989 Freight Car Annual FREIGHT Casdorph SOFCH 1989 $40.00 V 4 ST 58 exc Freight Cars Journal Monograph No 11 0884-027X 1 1994-1995 Transit Fact Book transit APTA APTA 1995 $10.00 v 2 SC 174 exc 1 20th Century NYC Beebe Howell North 1970 $30.00 V 4 HC 180 Exc 0-8310-7031-5 1 20th Century Limited NYC Zimmermann MBI 2002 $34.95 V 4 HC 156 NEW 0-7603-1422-5 1 30 Years Later, The Shore Line TRACTIN Carlson CERA 1985 $60.00 V 4 ST 32 exc Evanston - Waukegan 1896-1955 0-915348-00-4 1 35 Years, A History of the Pacific Coast Chapter R&LHS PCC R&LHS PCC R&LHS 1972 V 4 ST 64 exc 1 36 Miles of Trouble VT,SHORTLINES,EASTMorse Stephen Greene1979 $10.00 v 2 sc 43 exc 0-8289-0182-1 1 3-Axle Streetcars, Volume One trolley Elsner NJI 1994 $250.00 V 4 SC 178 exc #0539 of 1000 0-934088-29-2 -

Financial Statements and Financial Statistics 1985

CAISSE DE DEPOT ET_pj,C E ME NT DU QUEBEC FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AND FINANCIAL STATISTICS 1985 CAISSE DE DEPOT ET LACEMENT DU SUEBEC INVESTMENTS IN CORPORATE SECURITIES 1985 INVESTMENTS IN CORPORATE SECURITIES as at December 31, 1985 (at market value - in thousands of dollars) ENTERPRISES Shares Convertible Bonds Subtotal-frier Total Number Amount securities Agnico-Eagle Mines Limited 286,438 6,158 6,158 Aiberta Energy Company Ltd. 367,070 6,378 6,378 Alcan Aluminium Limited' 8,472,256 342,068 342,068 AMCA International Limited 594,260 9,359 9,359 American Express Company 71,900 5,304 5,304 Arnsterdam-Rotherdam Bank NV 105,801 6,153 6,153 Artopex International Inc.' 1,018,954 4,484 4,484 Asamera Inc.' 2,514,644 30,176 30,176 Bank of Montreal common 3,945,121 136,107 136,107 warrants 99,938 574 574 136,681 Bank of Montreal, Realty Inc. 5,190 5,190 Bank of Nova Scotia 9,507,848 135,487 10,984 146,471 Bell Canada Enterprises Inc. 10,795,413 454,757 29,537 484,294 Bow Valley Industries Ltd.' 3,223,717 44,729 44,729 Brascade Holdings Inc. common 126,000 1,077 1,077 preferred A, B, C, D 447,000 160,446 160,446 161,523 Brascade Resources Inc. 2,758,621 37,603 37,603 Brascan Limited class A 212,175 7,559 7,559 7,559 Bristol-Myers Company 54,300 5,041 5,041 Brunswick Mining and Smelting Corporation Limited 1,256,674 16,337 16,337 CAE Industries Ltd.