What Is Sustainable Development?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

Peter Hopkinson Is a Documentary Film-Maker Whose Life Has Ranged From

PETER HOPKINSON Peter Hopkinson is a documentary film-maker whose life has ranged from camerawork with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in the heyday of Hollywood to, more recently, the organisation of film production in the Central American state of Costa Rica. He entered the film industry before World War Two as a clapper- boy at Ealing Studios, and worked as a camera assistant at Alexander Korda’s Denham Studios. During the War he served with the Army Film and Photographic Unit filming on various battlefronts, and in its aftermath shot the first uncensored film in Soviet Russia. In 1946 he joined the celebrated American cine news magazine The March of Time as a director-reporter., filming in India, China, Japan, the middle East, Europe and the United States. For NBC he directed and photographed numerous international television reports and, for Louis de Rochemont, a prize-winning film on the Suez Canal. From the Council of Europe came a Special Award for a film profile of Britain in the Sixties; and the film he wrote and directed of the ending of colonial rule in Ghana, Nigeria and Sierra Leone, African Awakening, was selected for UNESCO’s Kalinga Prize as the one British film ‘judged to contribute most effectively to international co-operation in education, science and culture’. Producing, as well as directing, he has been working for some time on a series of films on natural resources, of which the first, Time for Tin, received a premier ‘Gold Camera’ Award at the United States Industrial Film and Video Festival. Sponsored by UNESCO, he undertook a study of world population pressures, A Matter of Families, filmed in India, Iran, Kenya and Venezuela. -

Session Slides

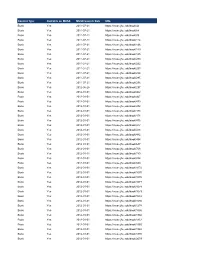

Content Type Available on MUSE MUSE Launch Date URL Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/42 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/68 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/89 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/114 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/146 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/149 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/185 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/280 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/292 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/293 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/294 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/295 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/296 Book Yes 2012-06-26 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/297 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/462 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/467 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/470 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/472 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/473 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/474 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/475 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/477 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/478 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/482 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/494 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/687 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/708 Book Yes 2012-01-11 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/780 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/834 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/840 Book Yes 2012-01-01 -

Newsletter 2013

The Old Papplewickian No.13 2013 THE HEADMASTER WRITES ld Boys who have visited the school since our new Front Entrance Hall was completed in September 2012 Ohave all commented on how this new development, located in the heart of the school, has given Papplewick a completely new ‘feel’…and I’m delighted to say that this seems to have been in an entirely positive way! However, Papplewick will always be more about people than buildings, and it is in this spirit that we are keen to continue to develop our links with Old Boys over the coming twelve months. The launch of an official Old Boys Facebook site is now imminent - I hope this will enable the school to organise social evenings for Old Boys in London while also helping Old Boys to network more easily amongst yourselves. A reunion for the first major overseas rugby tour to New Zealand in 1994 will take place at Papplewick in the summer, together with a reunion in Madrid for our Spanish families in May. We also intend to hold our first Old Boys versus Staff football match in the autumn although it may disappoint some of you that a similar rugby fixture is still some The Headmaster in Seoul for the Korean reunion last year, talking to way off! With the school in good heart, I hope such events will Simon Kim (2004-06). only help to strengthen the bond between Old Boys and Papplewick, and the school was in no better heart than in 2012 do please drop in whenever you feel inspired to do so – Sallie when senior boys won thirteen scholarships, including two and I would be absolutely delighted to see you either at academic scholarships to Eton and one to Winchester amongst Papplewick or at one of the forthcoming social events during a record haul of seven academic scholarships in total. -

New Genetics, New Social Formations

New Genetics, New Social Formations The genomic era requires more than just a technical understanding of gene structure and function. New technological options cannot survive without being entrenched in networks of producers, users and various services. New genetic technologies cut across a range of public domains and private lifeworlds, often appearing to gen- erate an institutional void in response to the complex challenges they pose. Chap- ters in this volume discuss a variety of these novel manifestations across both health and agriculture, including: gene banks intellectual property rights committees of inquiry non-governmental organisations (NGOs) national research laboratories These are explored in such diverse locations as Amazonia, China, Finland, Israel, the UK and the USA. This volume reflects the rapidly changing scientific, clinical and social environment within which new social formations are being constructed and reconstructed. It brings together a range of empirical and theoretical insights that serve to help better understand complex, and often contentious, innovative processes in the new genetic technologies. Peter Glasner is Professorial Fellow in the Economic and Social Research Council’s Centre for Economic and Social Aspects of Genomics at Cardiff University. He is Co-editor of the journals New Genetics and Society and 21st Century Society.He has a longstanding research interest in genetics, innovation and science policy. He is an Academician of the Academy of Learned Societies in the Social Sciences. Paul Atkinson is Distinguished Research Professor in Sociology at Cardiff University, where he is Associate Director of the ESRC Centre for Economic and Social Aspects of Genomics. He has published extensively on the sociology of medical knowledge and qualitative research methods. -

ISTH 2017 Final Program

XXVI ISTH Congress and 63rd Annual SSC Meeting LOREM IPSUM DOLOR LOREM IPSUM DOLOR XXVI ISTH Congress and 63rd Annual SSC Meeting FINAL PROGRAM www.isth2017.org 1 XXVI ISTH Congress and 63rd Annual SSC Meeting XXVI ISTH Congress and 63rd Annual SSC Meeting LOREM IPSUM DOLOR TABLE OF CONTENTS LOREM IPSUM DOLOR July 2017 VOLUME 11 | NUMBER 7 Editor in Chief: Mary Cushman Invitation and Welcome Messages 4–9 Congress Information ISTH 2017 Committees 10–13 ISTH 2017 Abstract Reviewers 14–18 Venue and Contacts 492 ISTH Council 19 Venue Floor Plans 494–503 ISTH SSC Committees 20 ISTH 2017 Attendee Services ISTH Awards 23 and Innovations 504–507 ISTH and ISTH 2017 Awards 24 Congress Information 508–513 ISTH 2017 Awards 25–27 ISTH 2017 Networking Events 515 About the ISTH 28–29 ISTH 2017 5K Charity Run/Walk 516 Local Information 518 A new open access Transportation in Berlin 519 Program journal from ISTH Program Overview 32–34 Supported Symposia and Program Day by Day 36–47 Product Theater Overview and Listing July 2017 Editor in Chief: Mary Cushman VOLUME 11 | NUMBER 7 Peer-Reviewed Open Access Journal Editor in Chief: Mary Cushman SSC and Educational Program 50–83 Now Open for Submissions Special Sessions 86–87 Exhibition and Congress Support 523 In this issue Nurses Forum 90–96 Supported Symposia Thrombotic complications of myeloproliferative neoplasms Research and Practice in Master Classes and and Product Theater Presentations 526–537 New recombinant FVIIa: pharmacokinetics and Career Development Sessions 98–108 efficacy Thrombosis and Haemostasis -

“A Correct and Progressive Road”: Us-Turkish Relations, 1945-1964

“A CORRECT AND PROGRESSIVE ROAD”: U.S.-TURKISH RELATIONS, 1945-1964 Michael M. Carver A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Committee: Dr. Douglas J. Forsyth, Advisor Dr. Gary R. Hess Dr. Marc V. Simon, Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Tiffany Trimmer 1 2011 Michael M. Carver All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT 2 Dr. Douglas Forsyth, Advisor This historical investigation of U.S.-Turkish relations from the end of World War II to 1964 provides a greater understanding of the challenges inherent in the formation and implementation of U.S. policy in Turkey at a time when the Turks embarked on multiparty politics and a determined campaign to become a modern and distinctly European nation through ambitious economic development programs. Washington proved instrumental in this endeavor, providing financial support through the Marshall Plan and subsequent aid programs, and political sponsorship of Turkey’s membership in international organizations such as NATO and the EEC. U.S. policymakers encountered various quandaries as they forged bilateral relations with the Turks, specifically reconciling democratization with Turkey’s development and participation in the containment of communism. The Turkish government under Adnan Menderes demonstrated its reliability as a U.S. ally, providing troops to fight in the Korean War and cooperating in the construction of NATO bases and the modernization of its military, but it came under increasing pressure from the political opposition when its economic policies failed to secure long-term economic growth and stability. Starting in the mid-1950s the Menderes government adopted increasingly authoritarian measures to control dissent, a problematic situation for Washington, as it desired greater Turkish democracy while at them same time did not wish to compromise the growing American military presence in Turkey. -

The Preventative and Healing Properties of Performing Arts in Female Genital Mutilation Alyssa Kardos

GEORGETOWN SCIENTIFIC Volume One Edition One RESEARCH JOURNAL February 2021 The Preventative and Healing Properties of Performing Arts in Female Genital Mutilation Alyssa Kardos 34 Georgetown Scientific Research Journal https://doi.org/10.48091/BNKO5024 The Preventative and Healing Properties of Performing Arts in Female Genital Mutilation Alyssa Kardos Department of International Health, Georgetown University, Washington, D.C., United States E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Despite being outlawed in many of the countries where it is the most prevalent, female genital mutilation (FGM) still persists. It is critical that innovative interventions be adopted in order to better address the cultural roots of this gender violence epidemic. The aim of this study is to explore the use of performing arts to fill this gap in effective preventative and treatment interventions. Due to the lack of data in this field, this study comprises of an extensive literature review. Existing programs were evaluated through thorough web searches, interviews of program leads, and analyses of the results. After reviewing existing evidence, it has been concluded that performing arts interventions provide positive outcomes in the field of FGM due to their ability to engage with cultural assumptions, incite empathy, and cross educational boundaries, all through community-connected approaches. Local outcomes were connected to government intervention in the recommendations to conclude that all governments should ban FGM, allocate public funds to the field of arts and health, and increase the validity of performance-based interventions through increased and improved research. Keywords: Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), Performing Arts, Performance, Theatre for Development 1.Introduction impacts of FGM in order to contribute to In the fight to end FGM, outlawing the meaningful change3. -

There Was a Man of UNRRA: Internationalism, Humanitarianism, and the Early Cold War in Europe, 1943-1947

There Was a Man of UNRRA: Internationalism, Humanitarianism, and the Early Cold War in Europe, 1943-1947 A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Amanda Melaine Bundy Graduate Program in History. The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Jennifer Siegel, Advisor Peter Hahn Robin Judd Copyrighted by Amanda Melaine Bundy 2017 Abstract This dissertation analyzes the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), a postwar humanitarian organization. UNRRA represented a new internationalist spirit in humanitarian cooperation, but its demise after only three years of operation reflects the emerging divisions between the Western democracies and the Soviet Union. UNRRA leadership and personnel faced daunting challenges in confronting the refugee crisis and rebuilding devastated nations. Because UNRRA was an innovation in international humanitarian cooperation, no precedent existed for those on the ground. Relief became politicized, as UNRRA staff sought to remain neutral in an increasingly bipolar context. In Greece and Italy, UNRRA implemented vital public health programs that eased the suffering of the populations in those nations. In Poland and Yugoslavia, UNRRA was caught between its neutral mission to provide relief to anyone in need, and the increasing pressure from the United States not to feed Communists. In Germany, leadership undermined the mission to provide help for displaced persons. In Ukraine and Byelorussia, American leadership overcame significant negative public opinion to deliver relief. Ultimately, UNRRA and the internationalism that created it fell victim to the breakdown of the postwar alliance. ii To my mother, Who loves and works with equal passion iii Acknowledgments A number of people deserve my deepest gratitude for their support. -

Catalog of Copyright Entries 1953 Motion Pictures and Filmstrips Jan

.N'^ CATALOG OF COPYRIGHT ENTRIES Third Series VOLUME 7, PARTS 12-13, NUMBER 1 Motion Pictures and Filmstrips JANUARY-JUNE 1953 o -^ * * ^ COPYRIGHT OFFICE THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON: 1953 CATALOG OF COPYRIGHT ENTRIES Third Series , CATALOG OF COPYRIGHT ENTRIES Third Series VOLUME 7, PARTS 12-13, NUMBER 1 Motion Pictures and Filmstrips JANUARY-JUNE 1953 COPYRIGHT OFFICE THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON: 1953 REMOVAL OF DEPOSITS FROM COPYRIGHT OFFICE NOTICE is given to authors, copyright proprietors and other lawful claimants that they may claim and remove before January 1, 1954, any article of the following named classes of published works deposited for copyright between January 1, 1950, and January 1, 1951, not reserved or dis- posed of as provided by sections 213 and 214 of Title 17 of the United States Code and still remaining in the files of the Copyright Office at the time of the request for their removal. The classes of pubhshed works covered by this notice are: Books and Pamphlets. Contributions to periodicals. Works of art; models or designs for works of art. Reproductions of a work of art. Drawings or plastic works of a scientific or technical char- acter. Photographs. Prints and pictorial illustrations excluding prints or labels used for articles of merchandise. Other published works and all unpublished works are excluded from this notice. The request for the removal of any copyright deposit should be signed by the person entitled thereto or his duly authorised agent. Such request should identify the work by stating the title, author, copyright proprietor, registration number and year of deposit, and should be addressed to the Copyright Office, Library of Congress, Washington 25, D. -

ASME IMECE 2018 Program

CONFERENCE EXHIBITION IMECE Nov 9 – 15, 2018 Nov 11 – 14, 2018 ONE GREAT LEARNING EXPERIENCE. INTERNATIONAL MECHANICAL ENGINEERING David L. Lawrence Convention Center, Pisburgh, PA CONGRESS & EXPOSITION Program The American Society of Mechanical Engineers® ASME® UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH | SWANSON SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING CELEBRATING 150 YEARS OF ENGINEERING EXCELLENCE Since the founding of the mechanical engineering program at the University of Pittsburgh in 1868, the Department of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science has built a strong reputation for academic excellence, innovation and advancing research. Core research competencies in the MEMS Degree programs (with a nearly 100 percent Department at Pitt include: placement rate): • Advanced Manufacturing and Design • Materials Science and Engineering (BS, MS, PhD) • Biomechanics and Medical Technologies • Mechanical Engineering (BS, MS, PhD) • Energy System Technologies • Nuclear Engineering (BS, MS) • Materials for Extreme Conditions • Engineering Sciences (BS) • Modeling and Simulation • Certificates in: Nuclear Engineering; Simulation in • Quantitative and In Situ Materials Characterization Design; and Processing, Properties, and Performance of Engineering Metals • Graduate Certificate in Nuclear Engineering is also offered online For more information visit engineering.pitt.edu/mems COUNTY OF ALLEGHENY RICH FITZGERALD COUNTY EXECUTIVE 3URFODPDWLRQ WHEREAS, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) will host its International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition -

1 PETER HOPKINSON Chapter Two – Film and Politics Back in 1936 Someone Had in Fact Succeeded in Putting It Can't Happen Here

PETER HOPKINSON THE SCREEN OF CHANGE Chapter Two – Film and Politics Back in 1936 someone had in fact succeeded in putting It Can’t Happen Here on the screen - or at least a snippet. In this filming the setting is a typical American middle-class home of the period. A knocking on the front door. The householder goes to answer. Enter a couple of uniformed bully boys. ‘What’s the trouble?’, asks Mr America. ‘We’re having a book burning on the green tomorrow night.’ ‘A what?’ ‘We’re goin’ to burn up all this subversive literature. A lot of smutty stuff that’s corrupting public morals - have you any objections?’ ‘Well, you won’t find any subversive books here...’ Over by the bookcase ‘Huh - now how about this one. Now this fellow Charles Dickens - wasn’t he a communist...?’ This filming has been established as taking place on stage, in a theatre, while voice-over informed us that ‘In twenty-one cities simultaneously, WPA actors appear in a dramatisation of It Can’t Happen Here, novelist Sinclair Lewis’s enactment of a Nazified US at the mercy of sedition-hunting fascist storm troopers.’ W.P.A. stood for the Works Progress Administration by way of which, in those Depression-dogged days, Roosevelt’s New Deal attempted to create jobs for the millions of American unemployed, in this case actors, playwrights and directors like Joseph Losey. 1 Titled ‘An Uncle Sam Production’, this extract from It Can’t Happen Here was just one item in a radically new but by then already established film series which, claiming to be ‘A New Form of Pictorial Journalism’, had already lit up American cinema screens with such as the controversy surrounding the newly created public power system of the Tennessee Valley Authority; the dictatorial ambitions of the then Governor of Louisiana, Huey Long; and the fascist-style broadcast preachings of the Irish-American prelate Father Charles E.