A Better European Architecture to Fight Money Laundering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2020

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Content Profile 3 Statement from the board 5 Developments in the payment system 8 Activities Activities: Point-of-sale payment system 11 Activities: Online payments 14 Activities: Giro-based payments 18 Activities: Stability of Payment Chains 23 Activities: Security in the payment system 25 Appendices Appendix: Board and management 30 Appendix: Governance 31 Appendix: List of members 33 2 Annual Report 2016 Profile The payment system is the bloodstream of our economy, has many stakeholders and is of great social importance. Therefore it has the characteristics of a utility. The many parties involved, the many relevant laws and regulations, the requirements for high quality, new technological possibilities and the high number of transactions make the payment system complex and dynamic. Transparency, openness, accessibility and dialogue with all stakeholders are important prerequisites in the payment system. The Dutch Payments Association organizes the collective tasks in the Dutch payment system for its members. Our members provide payment services on the Dutch market: banks, payment institutions and electronic money institutions. The shared tasks for infrastructure, standards and common product features are assigned to the Payments Association. We aim for a socially efficient, secure, reliable and accessible payment system. To this end, we deploy activities that are of common interest to our members. We are committed, meaningful and interconnecting in everything we do, to unburden our members where and when possible. We engage representatives of end users in the payment system, including businesses and consumers. On behalf of our members, we are visibly involved and accessible and we are socially responsible. -

Introduction: Our Athens Spring

Introduction: Our Athens Spring Let me tell you why I am here with words I have borrowed from a famous old manifesto. I am here because: A spectre is haunting Europe — the spectre of democracy. All the powers of old Europe have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this spectre: The state- sponsored bankers and the Eurogroup, the Troika and Dr Schäuble, Spain’s heirs of Franco’s political legacy and the SPD’s Berlin leadership, Baltic governments that subJected their populations to terrible, unnecessary recession and Greece’s resurgent oligarchy. I am here in front of you because a small nation chose to oppose this holy alliance. To look at them in the eye and say: Our liberty is not for sale. Our dignity is not for auction. If we give up liberty and dignity, as you demand that we do, Europe will lose its integrity and forfeit its soul. I am here in front of you because nothing good happens in Europe if it does not start from France. I am here in front of you because the Athens Spring that united Greeks and gave them back • their smile • their courage • their freedom from fear • the strength to say NO to irrationality • NO to un-freedom • NO to a subJugation that in the end does not benefit even Europe’s strong and mighty, …that magnificent Athens Spring, which culminated in a 62% saying a majestic NO to Un-Reason and to Misanthropy,… …our Athens Spring, was also a chance for a Paris Spring, a Frangy Spring, a Berlin, a Madrid, a Dublin, a Helsinki, a Bratislava, a Vienna Spring. -

Does Ownership Have an Effect on Accounting Quality?

Master Degree Project in Accounting Does Ownership have an Effect on Accounting Quality? Andreas Danielsson and Jochem Groenenboom Supervisor: Jan Marton Master Degree Project No. 2013:14 Graduate School Abstract Research on accounting quality in banks has evolved around the manipulation of the Loan Loss Provision and has been discussed in terms of earnings management and income smoothing. Key variables used to explain the manipulation of Loan Loss Provisions have been investor protection, legal enforcement, financial structure and regulations. This study will extend previous research by investigating the effect of state, private, savings and cooperative ownership on accounting quality. In this study data from more than 600 major banks were collected in the European Economic Area, covering annual reports between 2005 and 2011. Similar to prevalent research, the Loan Loss Provision is used as a central indicator of accounting quality. In contrast to existent literature, accounting quality is not explained by the manipulation of the Loan Loss Provision in terms of income smoothing or earnings management. Instead, accounting quality is addressed in terms of validity and argued to be an outcome of the predictive power of the Loan Loss Provision in forecasting the actual outcome of credit losses. The findings of this study confirm that ownership has an effect on accounting quality. All but one form of ownership investigated showed significant differences. State ownership was found to have a positive effect on accounting quality, both in comparison to private banks and all other banks. On the other hand, savings ownership was shown to have a negative impact on accounting quality compared to private and other banks. -

Stress Testing Governance, Risk Analytics and Instruments European Dr

VISIT OUR WEBSITE: www.flemingeurope.com “Linking the credit and liquidity risks” EXPERT ADVISORY BOARD nd ANNUAL DR. ANDREA BURGTORF Deutsche Bank, Germany, Head of Stress Testing HOP Governance, Risk Analytics and Instruments EUROPEAN S DR. LINda SLEDDENS Aegon Bank, Netherlands Senior Financial Risk Manager SUsaNNE HUGHES & WORK Lloyds Banking Group, UK STRess CE Senior Manager Stress Testing N PETER QUEll E R DZ Bank, Germany, Head of Portfolio Modelling E for Market and Credit Risk TESTING EXCLUSIVE SPEAKER PANEL CONF HEIKO HEssE for Banks IMF, USA, Economist, Monetary and Capital Markets Department 23-24 October 2013, Netherlands IaIN DE WEYMARN Bank of England, UK, Head of Banking System Division, Financial Stability Radisson Blu Hotel Amsterdam CAROLINE LIESEGANG EBA, UK, Senior Stress Testing Expert JEROME HENRY CONFERENCE & WORKSHOP ECB, Germany, Head of Financial Stability Assessment Division 2 Market conditions are in turmoil and a regulatory or risk management JAVIER VIllaR BURKE no one can be sure of the reaction. perspective. Moreover, you will be European Commission – DG ECFIN One of the ways of calming things able to benchmark your processes Statistical Officer down is reassuring the Financial and methodologies with your peers, environment about your ability regulators and gather diversity of ALEXANDER VasYUTOVIch to react promptly, safeguard your insights for your internal processes Promsvyazbank, Russia, Co-Chief Risk Officer clients’ interests and cope with improvement. Head of Financial and Retail Risk Management liquidity squeeze during stressed PETER QUEll periods. By incorporating stress To practice your stress testing DZ Bank, Germany, Head of Portfolio Modeling testing into your risk management techniques, we have prepared an for Market and Credit Risk methodologies, you are taking one intensive hands-on workshop called of the more important steps of doing Scenario Analysis in Stress Ewa RENZ so. -

List of PRA-Regulated Banks

LIST OF BANKS AS COMPILED BY THE BANK OF ENGLAND AS AT 1st February 2021 This document provides a list of Authorised Firms, it does not supersede the Financial Service Register which should be referred to as the most accurate and up to date source of information. Banks incorporated in the United Kingdom ABC International Bank Plc DB UK Bank Limited Access Bank UK Limited, The DF Capital Bank Limited Ahli United Bank (UK) PLC AIB Group (UK) Plc EFG Private Bank Limited Al Rayan Bank PLC Europe Arab Bank plc Aldermore Bank Plc Alliance Trust Savings Limited (Applied to Cancel) FBN Bank (UK) Ltd Allica Bank Ltd FCE Bank Plc Alpha Bank London Limited FCMB Bank (UK) Limited Arbuthnot Latham & Co Limited Atom Bank PLC Gatehouse Bank Plc Axis Bank UK Limited Ghana International Bank Plc GH Bank Limited Bank and Clients PLC Goldman Sachs International Bank Bank Leumi (UK) plc Guaranty Trust Bank (UK) Limited Bank Mandiri (Europe) Limited Gulf International Bank (UK) Limited Bank Of Baroda (UK) Limited Bank of Beirut (UK) Ltd Habib Bank Zurich Plc Bank of Ceylon (UK) Ltd Hampden & Co Plc Bank of China (UK) Ltd Hampshire Trust Bank Plc Bank of Ireland (UK) Plc Handelsbanken PLC Bank of London and The Middle East plc Havin Bank Ltd Bank of New York Mellon (International) Limited, The HBL Bank UK Limited Bank of Scotland plc HSBC Bank Plc Bank of the Philippine Islands (Europe) PLC HSBC Private Bank (UK) Limited Bank Saderat Plc HSBC Trust Company (UK) Ltd Bank Sepah International Plc HSBC UK Bank Plc Barclays Bank Plc Barclays Bank UK PLC ICBC (London) plc BFC Bank Limited ICBC Standard Bank Plc Birmingham Bank Limited ICICI Bank UK Plc BMCE Bank International plc Investec Bank PLC British Arab Commercial Bank Plc Itau BBA International PLC Brown Shipley & Co Limited JN Bank UK Ltd C Hoare & Co J.P. -

"SOLIZE India Technologies Private Limited" 56553102 .FABRIC 34354648 @Fentures B.V

Erkende referenten / Recognised sponsors Arbeid Regulier en Kennismigranten / Regular labour and Highly skilled migrants Naam bedrijf/organisatie Inschrijfnummer KvK Name company/organisation Registration number Chamber of Commerce "@1" special projects payroll B.V. 70880565 "SOLIZE India Technologies Private Limited" 56553102 .FABRIC 34354648 @Fentures B.V. 82701695 01-10 Architecten B.V. 24257403 100 Grams B.V. 69299544 10X Genomics B.V. 68933223 12Connect B.V. 20122308 180 Amsterdam BV 34117849 1908 Acquisition B.V. 60844868 2 Getthere Holding B.V. 30225996 20Face B.V. 69220085 21 Markets B.V. 59575417 247TailorSteel B.V. 9163645 24sessions.com B.V. 64312100 2525 Ventures B.V. 63661438 2-B Energy Holding 8156456 2M Engineering Limited 17172882 30MHz B.V. 61677817 360KAS B.V. 66831148 365Werk Contracting B.V. 67524524 3D Hubs B.V. 57883424 3DUniversum B.V. 60891831 3esi Netherlands B.V. 71974210 3M Nederland B.V. 28020725 3P Project Services B.V. 20132450 4DotNet B.V. 4079637 4People Zuid B.V. 50131907 4PS Development B.V. 55280404 4WEB EU B.V. 59251778 50five B.V. 66605938 5CA B.V. 30277579 5Hands Metaal B.V. 56889143 72andSunny NL B.V. 34257945 83Design Inc. Europe Representative Office 66864844 A. Hak Drillcon B.V. 30276754 A.A.B. International B.V. 30148836 A.C.E. Ingenieurs en Adviesbureau, Werktuigbouw en Electrotechniek B.V. 17071306 A.M. Best (EU) Rating Services B.V. 71592717 A.M.P.C. Associated Medical Project Consultants B.V. 11023272 A.N.T. International B.V. 6089432 A.S. Watson (Health & Beauty Continental Europe) B.V. 31035585 A.T. Kearney B.V. -

Thomas Wieser Director General Austrian Federal Ministry of Finance

Thomas Wieser Director General Austrian Federal Ministry of Finance VOWI_Tagung_2011.indb 134 03.10.11 08:28 Macroeconomic Imbalances within the EU: Short and Long Term Solutions What is an Imbalance? tion of countries, and may have impor- What is a macroeconomic imbalance? tant spillover effects. It has an array of And do macroeconomic imbalances lending instruments at its disposal that matter? Two easy questions. Put them can be utilized if imbalances lead to to an economist and she or he will most capital flows that are inadequate for likely give you an authoritative descrip- satisfying the external financing needs tion or definition of such an imbalance; of a country. The G 20 process has re- and will then proceed to authoritatively discovered this issue in the light of tell you that they either matter enor- global imbalances in current account mously, or not at all. A pattern will positions, and has agreed on a surveil- emerge: first, the definitions or de- lance exercise. scriptions will not be consistent with each other; second: if they matter, then usually abroad. I will start off with a simple defini- tion: a macroeconomic imbalance is the (negative or positive) position of a do- mestic, external or financial variable in relation to a certain norm. This posi- tion may – if uncorrected over time – make the national savings/investment balance so untenable that it self-cor- rects abruptly, thereby causing signifi- cant adjustment shocks domestically; in the case of large economies also abroad. Imbalances are caused by economic policies, or by their absence. They are Addressing Potential Imbalances in the Euro Area therefore a lagged indicator of other variables that developed at a pace or in a Within the European Union risks of direction that is not commensurate macroeconomic imbalances were rec- with the overall balanced development ognized in the Treaty. -

Eurogroup: Hans Vijlbrief Appointed President of the Eurogroup Working Group

PRESS Council of the EU EN PRESS RELEASE 25/18 22/01/2018 Eurogroup: Hans Vijlbrief appointed President of the Eurogroup working group The Eurogroup today appointed Hans Vijlbrief as the new President of the Eurogroup working group (EWG). He will take office as of 1 February 2018 and will serve a two-year term. He will succeed Thomas Wieser who was the first full-time EFC/EWG president and held the position since 2012. The President of the Eurogroup Working Group is elected by its members and then appointed by the Eurogroup. He was elected to this position by the EWG on 15 December 2017. The office of the President of the EWG is located at the General Secretariat of the Council of the EU, in Brussels. The EWG prepares the meetings of the Eurogroup and coordinates on euro-area specific matters. It is composed of representatives of the euro-area member states of the Economic and Financial Committee, the European Commission and the European Central Bank. Hans Vijlbrief will also serve as the President of the Economic and Financial Committee, which prepares the ECOFIN Council and promotes policy coordination among EU member states. He was elected to this position by the EFC on 15 December 2017. Until now, Hans Vijlbrief has held numerous positions at the ministry of economic affairs and at the ministry of finance of the Netherlands. Since October 2012, he has been serving as treasurer general at the ministry of finance of the Netherlands and a principal adviser to the minister of finance of the Netherlands on Eurogroup matters. -

Download (471Kb)

Pas toe of leg uit “Een onderzoek naar de toepassing van de code banken en de code verzekeraars ten aanzien van beloningsbeleid.” M.M. Scheffer Leeghwaterstraat 99 6717CX Ede Studentnummer: 2232146 [email protected] Rijksuniversiteit Groningen Faculteit economie & bedrijfskunde Accountancy & Controlling Ernst & Young Audit services Amsterdam / Utrecht 1e Begeleider RuG: Prof. dr. J.A. van Manen RA 2e Begeleider RuG: dr. O.P.G. Bik RA Begeleider E&Y: drs. M.T. Lemans RA M.M. Scheffer Pas toe of leg uit Voorwoord Voor u ligt mijn scriptie ter afronding van mijn master accountancy & controlling aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen. Ik heb het afgelopen jaar als zeer leerzaam en plezierig ervaren. Naast vakkennis heb ik mij in deze periode ook persoonlijk kunnen ontwikkelen. In deze scriptie staat corporate governance voor banken en verzekeraars centraal. Deze is vertaald in de code banken en de code verzekeraars. In deze scriptie is onderzoek gedaan naar de mate van naleving van de codes. Tevens is onderzocht in welke mate omvang van instellingen een rol speelt bij de naleving van de principes en tevens bij de kwaliteit van uitleg bij het niet toepassen van principes. Het onderzoek heb ik mogen uitvoeren bij mijn werkgever Ernst & Young te Utrecht. Graag wil ik mijn begeleider vanuit Ernst & Young, de heer drs. René Lémans RA, bedanken voor de begeleiding en hulp gedurende het gehele traject. Tevens wil ik de heren drs. Bob Leonards RA en mr. drs. Georges de Méris RA danken voor het meedenken en beantwoorden van mijn vakinhoudelijke vragen. Daarnaast wil ik graag mijn begeleiders vanuit de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, de heer Prof. -

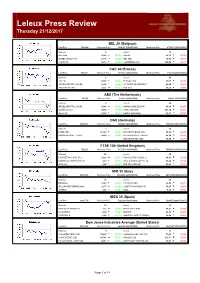

Leleux Press Review

Leleux Press Review Thursday 21/12/2017 BEL 20 (Belgium) Last Price 3994,68 Minimum Price 1046,07 (02/09/1992) Maximum Price 4759,01 (23/05/2007) Gainers 4 Losers 16 APERAM 43,85 +0,38% AGEAS 41,35 -0,79% ONTEX GROUP NV 27,75 +0,16% GBL (BE) 90,33 -0,79% COLRUYT 42,79 +0,03% COFINIMMO (BE) 110,00 -0,67% CAC 40 (France) Last Price 5352,77 Minimum Price 2693,21 (23/09/2011) Maximum Price 7347,94 (21/10/2009) Gainers 6 Losers 34 VALEO 62,09 +0,82% RENAULT SA 83,57 -0,98% ARCELORMITTAL SA (NL 26,98 +0,46% LAFARGEHOLCIM LTD (F 46,08 -0,96% VEOLIA ENV (FR) 21,27 +0,21% AXA (FR) 25,25 -0,88% AEX (The Netherlands) Last Price 547,38 Minimum Price 194,99 (09/03/2009) Maximum Price 806,41 (21/10/2009) Gainers 5 Losers 20 ARCELORMITTAL SA (NL 26,98 +0,46% KONINKLIJKE DSM NV 80,94 -0,93% GEMALTO N.V. 49,49 +0,29% ASML HOLDING 147,80 -0,90% RELX NV 19,24 +0,15% AHOLD DELHAIZE 18,33 -0,75% DAX (Germany) Last Price 13069,17 Minimum Price 7292,03 (26/11/2012) Maximum Price 13478,86 (03/11/2017) Gainers 2 Losers 28 LINDE (DE) 181,00 +0,58% DEUTSCHE BANK (DE) 16,64 -0,98% PROSIEBENSAT.1 NA O 29,00 +0,24% HEIDELBERGER ZEMENT 89,50 -0,92% DEUTSCHE TEL (DE) 15,00 -0,69% FTSE 100 (United Kingdom) Last Price 7525,22 Minimum Price 3277,50 (12/03/2003) Maximum Price 53548,10 (16/11/2009) Gainers 45 Losers 54 EASYJET PLC ORD 27 2 14,28 +0,97% ROYAL DUTCH SHELL A 24,05 -0,79% MARKS AND SPENCER GR 3,10 +0,97% ANGLO AMERICAN PLC O 14,88 -0,77% GKN (UK) 3,04 +0,91% SSE PLC ORD 50P 13,01 -0,77% MIB 30 (Italy) Last Price 22109,65 Minimum Price 12320,50 (24/07/2012) Maximum Price 48766,00 (05/04/2001) Gainers 13 Losers 26 BREMBO 12,80 +0,86% ATLANTIA SPA 26,45 -0,97% SALVATORE FERRAGAMO 21,75 +0,78% LUXOTTICA GROUP (IT) 50,95 -0,97% SAIPEM 3,63 +0,60% ENEL 5,28 -0,75% IBEX 35 (Spain) Last Price 10207,70 Minimum Price 5266,90 (10/10/2002) Maximum Price 15945,70 (08/11/2007) Gainers 15 Losers 19 BANCO DE SABADELL 1,72 +0,93% INDRA SISTEMAS 11,53 -0,98% CAIXABANK 4,00 +0,85% INDITEX 29,53 -0,92% IBERDROLA 6,58 +0,73% GAMESA CORP. -

39Th ECONOMICS CONFERENCE 2010

OESTERREICHISCHE NATIONALBANK EUROSYSTEM 39th ECONOMICS CONFERENCE 2011 The Future of European Integration: Some Economic Perspectives ECONOMICS CONFERENCE 2011 th 39 Contents Ewald Nowotny Welcome Address 4 Rudolf Hundstorfer The Future of European Integration – Some Economic Aspects 10 Session 1: Regaining Fiscal Strength, Restoring Growth Olli Rehn Keynote Address 16 Martin Wolf The Euro After the Crisis 22 Panel 1: Reforming Fiscal Policy Rules for the Euro Area Ernest Gnan Introductory Remarks 32 Wolfgang Franz Reforming Fiscal Policy Rules for the Euro Area 36 Daniela Schwarzer Legislative and Institutional Dynamics in Response to the Crisis 42 Klaus Liebscher Award Klaus Liebscher Award for Scientific Work on European Monetary Union and Integration Issues by Young Economists 50 Session 2: Banking and Financial Architecture in the EU Andreas Ittner Introductory Remarks 54 Lorenzo Bini Smaghi Macro-Prudential Supervision and Monetary Policy – Linkages and Demarcation Lines 58 David T. Llewellyn A Post Crisis Regulatory Strategy: The Road to “Basel N” or Pillar 4? 70 Panel 2: Enhancements in EU Financial Regulation: Have We Done Enough? Martin Summer Introductory Remarks 94 Hans-Helmut Kotz Enhancements in EU Financial Regulation: Have We Done Enough? 98 Andreas Pfingsten A Critical Assessment of the New Capital and Liquidity Requirements 110 2 39th ECONOMICS CONFERENCE 2011 VOWI_Tagung_2011.indb 2 03.10.11 08:25 Contents Session 3: Addressing Macroeconomic Imbalances Wolfgang Duchatczek Introductory Remarks 122 Anne O. Krueger Formulating -

The Netherlands

EXPORTING CORRUPTION 2020 ambassador in Nigeria shared confidential information with Shell about an investigation on THE NETHERLANDS location in Nigeria by Dutch financial police.6 The whistleblower who exposed the information, a local Limited enforcement staff member of the Netherlands embassy, was subsequently dismissed.7 Following the VimpelCom case, covered in the 3.1% of global exports Exporting Corruption Report 2018, there were three related cases in the Netherlands, two involving Investigations and cases banks and one involving an accounting and consulting firm (VimpelCom is now called VEON). In In the period 2016-2019, the Netherlands opened 16 September 2018, the NPPS settled its investigation investigations, commenced two cases and into ING Bank NV, with ING agreeing to pay €675 concluded three cases with sanctions. million (US$771 million) as a penalty and €100 million (US$114 million) as disgorgement to the Foreign bribery investigations are conducted by the NPPS.8 The FIOD had been investigating ING since Fiscal Intelligence and Investigations Service (FIOD) 2016 for suspected facilitation of international and the Netherlands Public Prosecution Service corruption and culpable money laundering.9 The (NPPS). These investigations take a long time to bank admitted “serious shortcomings” in executing conclude, due to their international and complicated policies to prevent financial crime. In July 2020, a 1 nature. group of victims won a court case requiring former In March 2019, a Shell statement on its website said ING CEO Ralph Hamers to testify about the bank’s that the NPPS was preparing charges against the role in relation to fraud by a third party, an issue company over an allegedly corrupt deal in Nigeria covered by the 2018 settlement.