Punishment and the Body in the Morant Bay Rebellion, 1865 By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After the Treaties: a Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. University of Southampton Department of History After the Treaties: A Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842 Michael Sivapragasam A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History June 2018 i ii UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Doctor of Philosophy After the Treaties: A Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842 Michael Sivapragasam This study is built on an investigation of a large number of archival sources, but in particular the Journals and Votes of the House of the Assembly of Jamaica, drawn from resources in Britain and Jamaica. Using data drawn from these primary sources, I assess how the Maroons of Jamaica forged an identity for themselves in the century under slavery following the peace treaties of 1739 and 1740. -

The Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica

timeline The Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica Questions A visual exploration of the background to, and events of, this key rebellion by former • What were the causes of the Morant Bay Rebellion? slaves against a colonial authority • How was the rebellion suppressed? • Was it a riot or a rebellion? • What were the consequences of the Morant Bay Rebellion? Attack on the courthouse during the rebellion The initial attack Response from the Jamaican authorities Background to the rebellion Key figures On 11 October 1865, several hundred black people The response of the Jamaican authorities was swift and brutal. Making Like many Jamaicans, both Bogle and Gordon were deeply disappointed about Paul Bogle marched into the town of Morant Bay, the capital of use of the army, Jamaican forces and the Maroons (formerly a community developments since the end of slavery. Although free, Jamaicans were bitter about ■ Leader of the rebellion the mainly sugar-growing parish of St Thomas in the of runaway slaves who were now an irregular but effective army of the the continued political, social and economic domination of the whites. There were ■ A native Baptist preacher East, Jamaica. They pillaged the police station of its colony), the government forcefully put down the rebellion. In the process, also specific problems facing the people: the low wages on the plantations, the ■ Organised the secret meetings weapons and then confronted the volunteer militia nearly 500 people were killed and hundreds of others seriously wounded. lack of access to land for the freed people and the lack of justice in the courts. -

John Eyre, the Morant Bay Rebellion in 1865, and the Racialisation of Western Political Thinking

wbhr 02|2012 John Eyre, the Morant Bay Rebellion in 1865, and the Racialisation of Western Political Thinking IVO BUDIL The main purpose of this study is to analyze the process of so-called ra- cialisation of the Western thinking in a concrete historical context of Brit- ish colonial experience in the second half of the nineteenth century. For most authors, the concept of racialisation was related to the Europeans´ response to their encounter with overseas populations in the course of global Western expansion from the early modern age. Frantz Fanon de- scribed the phenomenon of racialisation as a process by which the Euro- pean colonists created the “negro” as a category of degraded humanity: a weak and utterly irrational barbarism, incapable of self-government.1 However, I am convinced that the post-colonial studies established by Eric Williams and his followers emphasizing the role of racism as a strategy of vindication and reproduction of Western hegemony over overseas socie- ties and civilizations tend to neglect or disregard the emergence and the whole intellectual development of the racial vision of the human history and society with various functions, impacts and role within the Western civilization itself. Ivan Hannaford stressed that the idea of ancient Greeks to see peo- ple not in terms of their origin, blood relations, or somatic features, but in terms of membership of a public arena presented a crucial political achievement and breakthrough in human history.2 It created the concept of free political space we live in since -

History of Portland

History of Portland The Parish of Portland is located at the north eastern tip of Jamaica and is to the north of St. Thomas and to the east of St. Mary. Portland is approximately 814 square kilometres and apart from the beautiful scenery which Portland boasts, the parish also comprises mountains that are a huge fortress, rugged, steep, and densely forested. Port Antonio and town of Titchfield. (Portland) The Blue Mountain range, Jamaica highest mountain falls in this parish. What we know today as the parish of Portland is the amalgamation of the parishes of St. George and a portion of St. Thomas. Portland has a very intriguing history. The original parish of Portland was created in 1723 by order of the then Governor, Duke of Portland, and also named in his honour. Port Antonio Port Antonio, the capital of Portland is considered a very old name and has been rendered numerous times. On an early map by the Spaniards, it is referred to as Pto de Anton, while a later one refers to Puerto de San Antonio. As early as 1582, the Abot Francisco, Marquis de Villa Lobos, mentions it in a letter to Phillip II. It was, however, not until 1685 that the name, Port Antonio was mentioned. Earlier on Portland was not always as large as it is today. When the parish was formed in 1723, it did not include the Buff Bay area, which was then part of St. George. Long Bay or Manchioneal were also not included. For many years there were disagreements between St. -

COM 9660 Jodi-‐Ann Morris 1 the Morant Bay Rebellion of 1865 Was

COM 9660 Jodi-Ann Morris The Morant Bay Rebellion of 1865 was one of the major events in JamaiCan history, while under British rule, that stirred muCh debate on the lives of BlaCks. This rebellion was Catalyzed by the disCrimination, laCk of voting rights and soCial and eConomic inequality many BlaCks faCed in the years after slavery ended. In this uprising, there were some players that played signifiCant roles in the revolt. These persons are George William Gordon, Paul Bogle and Governor Edward (John) Eyre. These men defined JamaiCan history not only with their aCtions, words and tenaCity but also with the aid publiCations and printed material. Paul Bogle and George William Gordon was advoCate for the better treatments of the poor and ill- treated in Jamaica. Gordon, the son of an affluent white Jamaican planter and a Negro slave, he was eduCated, free and had a growing reputation as a wealthy farmer and “aCtive reformer” in changing societal inequalities. Paul Bogle was a Baptist minister, who had befriended Gordon, was very voCal in his Community about the injustiCes taking plaCe in the Country. There were several ways that they employed in order to get their ideas to those affected. One of the ways they did this was through Gordon’s newspaper, Jamaica Watchman and the People’s Free Press. In one of its publication, it made mention of the “Underhill Convention” whiCh was created as a result of a letter written by Edward Bean Underhill, the seCretary of the Baptist Missionary SoCiety that was made publiC. In this letter, he talks about the struggle that the people are facing the lack of paid work acCompany with high taxation and little to no politiCal or judiCial rights. -

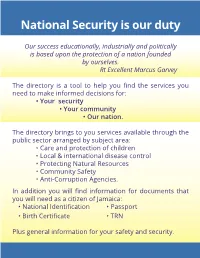

Resource Directory Is Intended As a General Reference Source

National Security is our duty Our success educationally, industrially and politically is based upon the protection of a nation founded by ourselves. Rt Excellent Marcus Garvey The directory is a tool to help you find the services you need to make informed decisions for: • Your security • Your community • Our nation. The directory brings to you services available through the public sector arranged by subject area: • Care and protection of children • Local & international disease control • Protecting Natural Resources • Community Safety • Anti-Corruption Agencies. In addition you will find information for documents that you will need as a citizen of Jamaica: • National Identification • Passport • Birth Certificate • TRN Plus general information for your safety and security. The directory belongs to Name: My local police station Tel: My police community officer Tel: My local fire brigade Tel: DISCLAIMER The information available in this resource directory is intended as a general reference source. It is made available on the understanding that the National Security Policy Coordination Unit (NSPCU) is not engaged in rendering professional advice on any matter that is listed in this publication. Users of this directory are guided to carefully evaluate the information and get appropriate professional advice relevant to his or her particular circumstances. The NSPCU has made every attempt to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information that is published in this resource directory. This includes subject areas of ministries, departments and agencies (MDAs) names of MDAs, website urls, telephone numbers, email addresses and street addresses. The information can and will change over time by the organisations listed in the publication and users are encouraged to check with the agencies that are listed for the most up-to-date information. -

A Mighty Experiment: the Transition from Slavery To

A MIGHTY EXPERIMENT: THE TRANSITION FROM SLAVERY TO FREEDOM IN JAMAICA, 1834-1838 by ELISABETH GRIFFITH-HUGHES (Under the Direction of Peter C. Hoffer) ABSTRACT When Britain abolished slavery, in 1834, it did not grant immediate freedom to the slaves, but put in place an apprenticeship period of four to six years depending upon occupation designation. This period, along with compensation of 6 million pounds, was awarded to the planters for their property losses. It was meant to be used to "socialize" the former slaves and convert them from enslaved to wage labor. The British government placed the task of overseeing the apprenticeship period in the hands of a force of stipendiary magistrates. The power to punish the work force was taken from the planters and overseers and given to the magistrates who ruled on the complaints brought by planters, overseers, and apprentices, meted out punishments, and forwarded monthly reports to the governors. Jamaica was the largest and most valuable of the British West Indian possessions and consequently the focus of attention. There were four groups all with a vested interest in the outcome of the apprenticeship experiment: the British government, the Jamaican Assembly, the planters, and the apprentices. The thesis of this work is that rather than ameliorating conditions and gaining the cooperation they needed from their workers, the planters responded with coercive acts that drove the labor force from the plantations. The planters’ actions, along with those of a British government loathe to interfere with local legislatures after the experience of losing the North American colonies, bear much of the responsibility for the demise of the plantation economy in Jamaica. -

Roger Mais and George William Gordon

KARINA WILLIAMSON Karina Williamson is retired. She was university lecturer in English Literature at Oxford and Edinburgh, has researched, taught and published on 20th century Caribbean literature, and has just edited the Jamaican novel Marly (1828) for the Caribbean Classics series. She is now preparing an anthology of poems on slavery and abolition, 1700-1834. ______________________________________________________________________ The Society For Caribbean Studies Annual Conference Papers edited by Sandra Courtman Vol.3 2002 ISSN 1471-2024 http://www.scsonline.freeserve.co.uk/olvol3.html _____________________________________________________________________ RE-INVENTING JAMAICAN HISTORY: ROGER MAIS AND GEORGE WILLIAM GORDON Karina Williamson Abstract This paper represents the convergence of two lines of interest and research: (1) in concepts and uses of history in Caribbean literature; (2) in the Jamaican writer Roger Mais. George William Gordon comes into the picture both as a notable figure in Jamaican history and as a literary subject. Gordon, a coloured man, was Justice of the Peace and representative of St Thomas in the East in the House of Assembly in the 1860s. Although he was a prosperous landowner himself, he fought vigorously on behalf of black peasants and smallholders against members of the white plantocracy, and was an outspoken critic of Governor Eyre in the Assembly. After the Morant Bay rebellion in 1865 he was arrested on Eyre’s orders and executed for his alleged implication in the rebellion. In 1965 he was named as a National Hero of Jamaica, alongside Paul Bogle, 1 leader of the rebellion. In a now almost forgotten play George William Gordon, written in the 1940s, Roger Mais dramatised Gordon’s involvement in the events of 1865.[1] Mais was not the first or last writer to turn Gordon into a literary hero or to recast the rebellion in fictional terms, but his reinvention of this historic episode is of peculiar interest because it is connected with events which earned Mais himself a small but unforgotten niche in modern Jamaican history. -

Notice of Route Taxi Fare Increase

Notice of Route Taxi Fare Increase The Transport Authority wishes to advise the public that effective Monday, August 16, 2021, the rates for Route Taxis will be increased by 15% from a base rate of $82.50 to $95.00 and a rate per kilometer from $4.50 to $5.50. How to calculate the fare: Calculation: Base Rate + (distance travelled in km x rate per km). Each fare once calculated is rounded to the nearest $5.00 The Base Rate and Rate per km can be found below: Rates: Base Rate (First km): $95.00 Rate for each additional km (Rate per km): $5.50 Calculation: Base Rate + (distance travelled in km x rate per km) Example: A passenger is travelling for 15km, the calculation would be: 95.00 + (15 x 5.50) = $177.50. The fare rounded to the nearest $5 would be $180. Below are the fares to be charged along Route Taxi routes island-wide. N.B. Children, students (in uniform), physically disabled and senior citizens pay HALF (1/2) the fare quoted above. Kingston and St. Andrew Origin Destination New Fare CHISHOLM AVENUE DOWNTOWN $ 130 JONES TOWN DOWNTOWN $ 130 MANLEY MEADOWS DOWNTOWN $ 115 PADMORE CHANCERY STREET $ 115 CYPRESS HALL CHANCERY STREET $ 150 ESSEX HALL STONY HILL $ 145 MOUNT SALUS STONY HILL $ 120 FREE TOWN LAWRENCE TAVERN $ 150 GLENGOFFE LAWRENCE TAVERN $ 140 MOUNT INDUSTRY LAWRENCE TAVERN $ 170 HALF WAY TREE MAXFIELD AVENUE $ 110 ARNETT GARDENS CROSS ROADS $ 110 TAVERN/ KINTYRE PAPINE $ 115 MOUNT JAMES GOLDEN SPRING $ 110 N.B. Children, students (in uniform), physically disabled and senior citizens pay HALF (1/2) the fare quoted above. -

New Museum School Podcast Transcript– 2019/2020

New Museum School Podcast Transcript– 2019/2020 PODCAST TITLE: Think a likkle: lineage of thought NMS TRAINEE: Ellie Ikiebe HOST INSTITUTION: National Trust – Marketing & Comms SCRIPT NMS INTRO STING LINK 1 Hi, I’m Ellie. I’m part of a work-based learning programme called the New Museum School. I’m part of the National Trust’s London Marketing and Communications Team, and I work with the Trust’s smaller London properties. That involves Carlyle’s House, Fenton House, and 2 Willow Road - and I’m enJoying it… LINK 2 On a crisp October morning, I exited Sloane Square station to a warm welcome and hug from Lin. She’s been the live-in custodian of Carlyle’s House for over 20 years. She’s lovely. We crossed Sloane Square and walked to Carlyle’s House in Cheyne Walk. We spoke about how the area had changed. Away from the posh shops and eateries, we turned the corner into a quiet street. It’s been a hundred and thirty-nine years since Thomas and Jane Carlyle lived there, but walking into the house was like walking back in time.. 1 Company registered in England and Wales Cultural Co-operation 2228599 Registered Charity 801111 trading as Culture& LINK 3 The entrance is impactful. The walls are dark and intense. Lin explains the walls were wallpapered with imitation oak wallpaper, then varnished to avoid bugs and cover cracks. The original colour was much brighter back in the day. Now they have darkened over time as they age. It takes care and effort to conserve the house. -

Jamaica a Country Profile

Jamaica A Country Profile 1983 Offlc'e of U.S,. Foreign Disaster Assistance Agency for International Development Washington, D.C. 2052L 78000' .71Q 7703P 7700,76-30' E~~~ahm-oulth CAR I B;BEANi.. SEA [ i/: LueMneoByRunaway Bay -f18030 , eadingSaint Anns Bay ~Montpelier.. JAM ES TRELA / SA.IPort, Maria WEOEL N" M Annotto Bay Fr an kfi e l d : SA T hri ,CLWalkTw"" ! \ - --... ,. H \ % i\ Chapelton'-¥ " AI T " ',. _ ZeOO0 Black River THE Nr.¥EI AN k T 'O0 •~~~ sil Half Way T a'r e J[ ' - 8 JA MA ICA. .liao.:587 ' ,L,; d.-:, " I.i HarA,u[ ay'.-" 0 20 A0 f-I Ameter SEA ( National capital 0 Parish capital -. :- . - Railroad ... "", ." .. .. ' -"Ra: AN E7EP' Pe -. 6 o 0 o,o .o.,.. ~ CA R-IZBB E A N- • "O 0 20 Kilometers S E A.::+f . : :., i,: ...:. _ - V 710-1 . :!.:.:. """i! : ; (-6.:,Of: " •Base 58783 11.6B8 JAMAICA: A COUNTRY PROFILE prepared for The Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance Agency for International Development Department of State Vashington, D.C. 20523 by Evaluation Technologies, Inc. Arlington, Virginia under contract AID/SOD/PDC-C-2112 The Country Profile Series is designed to provide baseline country data in support of the planning and relief operations of the Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA). Format and content have evolved over the last several years to emphasize disaster vulnerability, planning, and resources. We hope th&t the information provided is also useful to other individuals and organizations involved in disaster-relatod activities. Every effort is made to obtain current, reliable data; unfortunately it is not possible to issue updates as fast as changes would warrant. -

The Jamaican Marronage, a Social Pseudomorph: the Case of the Accompong Maroons

THE JAMAICAN MARRONAGE, A SOCIAL PSEUDOMORPH: THE CASE OF THE ACCOMPONG MAROONS by ALICE ELIZABETH BALDWIN-JONES Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2011 8 2011 Alice Elizabeth Baldwin-Jones All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT THE JAMAICAN MARRONAGE, A SOCIAL PSEUDOMORPH: THE CASE OF THE ACCOMPONG MAROONS ALICE ELIZABETH BALDWIN-JONES Based on ethnography, oral history and archival research, this study examines the culture of the Accompong Maroons by focusing on the political, economic, social, religious and kinship institutions, foodways, and land history. This research demonstrates that like the South American Maroons, the Accompong Maroons differ in their ideology and symbolisms from the larger New World population. However, the Accompong Maroons have assimilated, accommodated and integrated into the state in every other aspect. As a consequence, the Accompong Maroons can only be considered maroons in name only. Today’s Accompong Maroons resemble any other rural peasant community in Jamaica. Grounded in historical analysis, the study also demonstrate that social stratification in Accompong Town results from unequal access to land and other resources, lack of economic infrastructure, and constraints on food marketeers and migration. This finding does not support the concept of communalism presented in previous studies. Table of Contents Page Part 1: Prologue I. Prologue 1 Theoretical Resources 10 Description of the Community 18 Methodology 25 Significance of the Study 30 Organization of the Dissertation 31 Part II: The Past and the Present II. The Political Structure – Past and Present 35 a.