The Right Wrong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Acquittal of John Demjanjuk and Its Impact on the Future of Nazi War Crimes Trials Lisa J

Boston College International and Comparative Law Review Volume 18 | Issue 1 Article 4 12-1-1995 Not Guilty – But Not Innocent: An Analysis of the Acquittal of John Demjanjuk and its Impact on the Future of Nazi War Crimes Trials Lisa J. Del Pizzo Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/iclr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Lisa J. Del Pizzo, Not Guilty – But Not Innocent: An Analysis of the Acquittal of John Demjanjuk and its Impact on the Future of Nazi War Crimes Trials, 18 B.C. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 137 (1995), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/iclr/vol18/iss1/4 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Not Guilty-But Not Innocent: An Analysis of the Acquittal of John Demjanjuk and Its Impact on the Future of Nazi War Crimes Trials INTRODUCTION On July 29, 1993, the Supreme Court of the State of Israel acquit ted John Demjanjuk of charges that he was "Ivan the Terrible," a sadistic Nazi gas chamber operator who assisted in the extermina tion of thousands of Jews at the Treblinka death camp in Poland during World War II.! The acquittal, which overturned the district court's 1988 conviction and death sentence,2 was based on new evidence which created a "reasonable doubt" that Demjanjuk was "Ivan the Terrible" of Treblinka.3 The acquittal of John Demjanjuk comes after a sixteen year legal battle which began in the United States in 1977, when the U.S. -

Holocaust Archaeology: Archaeological Approaches to Landscapes of Nazi Genocide and Persecution

HOLOCAUST ARCHAEOLOGY: ARCHAEOLOGICAL APPROACHES TO LANDSCAPES OF NAZI GENOCIDE AND PERSECUTION BY CAROLINE STURDY COLLS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Institute of Archaeology and Antiquity College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The landscapes and material remains of the Holocaust survive in various forms as physical reminders of the suffering and persecution of this period in European history. However, whilst clearly defined historical narratives exist, many of the archaeological remnants of these sites remain ill-defined, unrecorded and even, in some cases, unlocated. Such a situation has arisen as a result of a number of political, social, ethical and religious factors which, coupled with the scale of the crimes, has often inhibited systematic search. This thesis will outline how a non- invasive archaeological methodology has been implemented at two case study sites, with such issues at its core, thus allowing them to be addressed in terms of their scientific and historical value, whilst acknowledging their commemorative and religious significance. -

PDF Van Tekst

Vooys. Jaargang 12 bron Vooys. Jaargang 12. Vooys, Utrecht 1993-1994 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_voo013199401_01/colofon.php © 2012 dbnl i.s.m. 2 [Nummer 1] Het fijne raadsel Over de heterodoxie van de kunst1 Redbad Fokkema ‘Elke kunstenaar houdt zich in zekere zin bezig met metafysica, ook al is zijn werk aards bepaald. En omgekeerd zal het wel hetzelfde zijn.’ Gerrit Kouwenaar (1963) Aan het slot van de roman Houtekiet (1939) van Gerard Walschap bekeert Houtekiet, de natuurmens die van God en maatschappij los is, zich in zekere zin. Als de hoogmis begint, gaat hij niet de kerk binnen, maar beklimt hij de toren. Er staat dan: Niemand heeft Jan Houtekiet kunnen overtuigen dat het beter was naar [...] onnozele preken te luisteren en dat hij daar hoog niet dichter bij God zat dan in de duffe kerk. Hij zat daar niet te prevelen of kruiskens te maken. Hij keek rustig over de velden en in de lucht. En hij voelde zich één met de oneindigheid, waarin onvatbaar voor woorden en gedachten, dat fijne raadsel zweeft [...] dat ons allen boeien blijft in dit aardse leven. Aan deze inwisseling van dogmatische orthodoxie voor een algemene religiositeit - een betrokkenheid op de werkelijkheid en de onwerkelijkheid waarover de ratio zwijgt - moest ik denken toen ik het boekje Over God las, dat in 1983 verscheen. Zeven jonge auteurs schrijven er over de betekenis van hun protestantse dan wel roomse opvoeding voor hun huidig godsidee of godservaring. Oek de Jong had graag het idee God allang vervangen gezien door het idee van het Verhevene: ‘Ieder kan namelijk, zonder enig zielsconflict, ervaren dat de poëzie tot het Verhevene behoort. -

The Barnes Review SOBIBÓR a JOURNAL of NATIONALIST THOUGHT & HISTORY HOLOCAUSTPROPAGANDAANDREALITY VOLUME XVI NUMBER 4 JULY/AUGUST 2010 BARNESREVIEW.ORG

WHAT IS THE TRUTH ABOUT THE SOBIBOR CONCENTRATION CAMP? FIND OUT! BRINGING HISTORY INTO ACCORD WITH THE FACTS IN THE TRADITION OF DR. HARRY ELMER BARNES The Barnes Review SOBIBÓR A JOURNAL OF NATIONALIST THOUGHT & HISTORY HOLOCAUSTPROPAGANDAANDREALITY VOLUME XVI NUMBER 4 JULY/AUGUST 2010 BARNESREVIEW.ORG A scholarly examination of the infamous Nazi “death camp” NEW FROM TBR: By Juergen Graf, Carlo Mattogno & Thomas Kues n May 2009, the 89-year-old Cleveland autoworker John Demjanjuk was deported from the United States to Germany, where he was arrested and charged with aiding and abetting murder in at least 27,900 cases. These mass murders were allegedly perpetrated at the Sobibór “death” Icamp in eastern Poland. According to mainstream historiography, 170,000 to 250,000 Jews were exterminated here in gas chambers between May 1942 and October 1943. The corpses were buried in mass graves and later incinerated on an open-air pyre. A DAGGER IN THE But do these claims really stand up to scrutiny? SOBIBOR In this book, the official version of what transpired at LEGEND Sobibór is put under the scanner. It is shown that the historiog- raphy of the camp is not based on solid evidence, but on the selec- tive use of eyewitness testimonies, which in turn are riddled with con- tradictions and outright absurdities. Could this book exonerate falsely accused John Demjanjuk? For more than half a century mainstream Holocaust historians made no real attempts to muster material Also in this issue: evidence for their claims about Sobibór. Finally, in the 21st century, professional historians carried out an archeological survey at the former camp site. -

The Aftermath of Nuremberg . . . the Problems of Suspected War

NYLS Journal of Human Rights Volume 6 Article 8 Issue 2 Volume VI, Part Two, Spring 1989 1989 The Aftermath of Nuremberg . The rP oblems of Suspected War Criminals in America Natalie J. Sobchak Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/journal_of_human_rights Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Sobchak, Natalie J. (1989) "The Aftermath of Nuremberg . The rP oblems of Suspected War Criminals in America," NYLS Journal of Human Rights: Vol. 6 : Iss. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/journal_of_human_rights/vol6/iss2/8 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Journal of Human Rights by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. THE AFrERMATH OF NUREMBERG... THE PROBLEMS OF SUSPECTED WAR CRIMINALS IN AMERICA L INTODUCrON Treblinka. Auschwitz. Sobibor. The mere mention of these places and others like them is a devastating reminder of the ultimate experience in human suffering. These were a few of the many concentration camps -- death camps -- designed to carry out Hitler's Final Solution: to exterminate as many Jews, Slavs, Gypsies, and Homosexuals as possible and create a supreme Aryan' society. Millions upon millions of innocent civilians would suffer miserable deaths before the liberation would come.2 Who were these per- secutors? While the Nazis3 devised "the plan," supplied the materials and man-power to build the camps, and supervised these atrocities, only a few of the death camps were actually located in Germany. The camps were situated in various Slavic countries which had capitulated under Nazi onslaught.' To assist them in their crimes, the Nazis obtained the cooperation of some of the local people and prisoners of war.' Whether their participation was voluntary or not, 1. -

Introduction Norman J.W

Introduction Norman J.W. Goda E The examination of legal proceedings related to Nazi Germany’s war and the Holocaust has expanded signifi cantly in the past two decades. It was not always so. Though the Trial of the Major War Criminals at Nuremberg in 1945–1946 generated signifi cant scholarly literature, most of it, at least in the trial’s immediate aftermath, concerned legal scholars’ judgments of the trial’s effi cacy from a strictly legalistic perspective. Was the four-power trial based on ex post facto law and thus problematic for that reason, or did it provide the best possible due process to the defendants under the circumstances?1 Cold War political wrangl ing over the subsequent Allied trials in the western German occupation zones as well as the sentences that they pronounced generated a discourse that was far more critical of the tri- als than laudatory.2 Historians, meanwhile, used the records assembled at Nuremberg as an entrée into other captured German records as they wrote initial studies of the Third Reich, these focusing mainly on foreign policy and wartime strategy, though also to some degree on the Final Solution to the Jewish Question.3 But they did not historicize the trial, nor any of subsequent trials, as such. Studies that analyzed the postwar proceedings in and of themselves from a historical perspective developed only three de- cades after Nuremberg, and they focused mainly on the origins of the initial, groundbreaking trial.4 Matters changed in the 1990s for a number of reasons. The fi rst was late- and post-Cold War interest among historians of Germany, and of other nations too, in Vergangenheitsbewältigung—the political, social, and intellectual attempt to confront, or to sidestep, the criminal wartime past. -

Britannica's Holocaust Resources

Britannica’s Holocaust Resources Britannica has opened up a large portion of its database on the Holocaust: more than 100 articles, essays, and lesson / classroom prompts, some of which also contains photographs and videos. Many of the articles have been written by Dr. Michael Berenbaum, an internationally known scholar with a stellar reputation in Holocaust studies and the former director of the Research Institute at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. In essence, Britannica is offering a free encyclopedia of the Holocaust as part of a new partnership with a number of eductional institutions. More about this project can be found HERE . These Britannica articles provide an unmatched resource, and not just for teachers and students. It will certainly be of interest to anyone who would like a convenient, reliable resource for Holocaust-related information. Part 1: Hitler and the Origins of the Holocaust • ADOLF HITLER • ANTI - SEMITISM • KLAUS BARBIE • BEER HALL PUTSCH • E V A B R A U N • ADOLF EICHMANN • GENOCIDE • GESTAPO • H A N S F R A N K • HERMANN GÖRING • JULIUS STREICHER • REINHARD HEYDRICH • RUDOLF HESS • HEINRICH HIMMLER • KRISTALLNACHT • M E I N K A M P • N A Z I P A R T Y • NÜRNBERG LAWS • FRANZ VON PAPEN • ALFRED ROSENBERG • SA • SS • SWASTIKA • T HYSSEN FAMILY DISCUSSION QUESTIONS Part 2: The Holocaust • THE HOLOCAUST • NON - JEWISH VICTIMS OF TH E HOLOCAUST • A N N E F R A N K • THE DIARY OF ANNE FR ANK • MORDECAI ANIELEWICZ • ALFRIED KRUPP VON BO HLEN UND HALBACH • AUSCHWITZ • B A B Y Y A R • BELZEC • BERGEN - BELSEN • BUCHENWALD -

A New Definition of a War Criminal: Present Day Nazi War Criminal Prosecutions

A NEW DEFINITION OF A WAR CRIMINAL: PRESENT DAY NAZI WAR CRIMINAL PROSECUTIONS Jennifer Snyder INTRODUCTION As early as 1942, the Allied Powers were determined to punish the Axis war criminals.1 The leaders of the United States, Great Britain, and Soviet Union jointly vowed to prosecute those responsible for the crimes against the civilian population; particularly those crimes involving the mass murders of the European Jewish population.2 The Moscow Declaration, signed by the United States, United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, stated that at the time of Armistice, those who had been determined responsible for war crimes would be sent back to their home country and would be tried according to the laws of their homeland.3 The majority of the post-1945 war crime trials consisted of lower level officials and functionaries.4 At first, the U.S., Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union focused on perpetrators in their respective zones of occupations – many trials involved the murder of captured Allied military personnel by Germans or Axis troops.5 Over time, the Allied powers expanded their judicial mandate to include the commandants, concentration camp guards, and others who had committed crimes against Jews.6 In the decades following World War II, both the German Federal Republic (West Germany) and the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) continued to try Nazi-era defendants.7 To date, the Federal Republic has held 925 proceedings trying defendants of the Nazi era war crimes.8 Subsequently, many of those trials ended in acquittals, light sentences due to the aging of the defendant, or defendants who claimed superior orders.9 1 War Crimes Trials, UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM HOLOCAUST ENCYCLOPEDIA (August 18, 2015), http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10005140. -

Holocaust Center Events Spring 2016

Holocaust Education and Programming Center Spring 2016 Calendar of Events January 28, 2016, 6pm, Manzulli Board Room, Foundation Hall Erasing Jewish Vienna: The 1943 Gustav Klimt Retrospective Laura Morowitz, Professor of Art History International Holocaust Remembrance Day-71st Anniversary Auschwitz Liberation Dr. Laura Morowitz, Professor of Art History at Wagner College, is currently writing a book examining art in Jewish Vienna in relation to cultural erasure. Last year she taught a course on Nazi Art and Aesthetics at Wagner College. She served as researcher for a novel on Adele Bloch Bauer painting by Klimt, Woman in Gold, to be published by Atria (Simon and Schuster) in 2016. *Light kosher dinner. Free. Please call for reservation 718-390-3253. Sunday, January 31, 2016, 3-5pm, Manzulli Board Room, Foundation Hall Holocaust Remembrance Readings. Co-hosted by Theater Major Jazmine Minner and Prof. Lori Weintrob, with SIOutLoud. Featuring Wagner's Hillel President and Theater Major Adam Goldenberg in the play Dr. Korczak and the Children (excerpt). Staten Island OutLOUD presents a special afternoon of readings and conversation. *Kosher falafel and cookies served. February 24th, 4:30, Spiro Hall 2 WWII Veteran William Morris Jr.: Eyewitness to D-Day From Omaha Beach to confrontations with the German Military, William Morris assisted in the Allied defeat of the Nazis, even as he experienced racism. These experiences were recently published in a children’s book by Dolores Morris, his daughter, The Dog That Wagged her Tail: A Black Veteran’s Story World War II. Both father and daughter will answer questions about these experiences. William Morris Jr. -

Filming the End of the Holocaust War, Culture and Society

Filming the End of the Holocaust War, Culture and Society Series Editor: Stephen McVeigh, Associate Professor, Swansea University, UK Editorial Board: Paul Preston LSE, UK Joanna Bourke Birkbeck, University of London, UK Debra Kelly University of Westminster, UK Patricia Rae Queen’s University, Ontario, Canada James J. Weingartner Southern Illimois University, USA (Emeritus) Kurt Piehler Florida State University, USA Ian Scott University of Manchester, UK War, Culture and Society is a multi- and interdisciplinary series which encourages the parallel and complementary military, historical and sociocultural investigation of 20th- and 21st-century war and conflict. Published: The British Imperial Army in the Middle East, James Kitchen (2014) The Testimonies of Indian Soldiers and the Two World Wars, Gajendra Singh (2014) South Africa’s “Border War,” Gary Baines (2014) Forthcoming: Cultural Responses to Occupation in Japan, Adam Broinowski (2015) 9/11 and the American Western, Stephen McVeigh (2015) Jewish Volunteers, the International Brigades and the Spanish Civil War, Gerben Zaagsma (2015) Military Law, the State, and Citizenship in the Modern Age, Gerard Oram (2015) The Japanese Comfort Women and Sexual Slavery During the China and Pacific Wars, Caroline Norma (2015) The Lost Cause of the Confederacy and American Civil War Memory, David J. Anderson (2015) Filming the End of the Holocaust Allied Documentaries, Nuremberg and the Liberation of the Concentration Camps John J. Michalczyk Bloomsbury Academic An Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc LONDON • OXFORD • NEW YORK • NEW DELHI • SYDNEY Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2014 Paperback edition fi rst published 2016 © John J. -

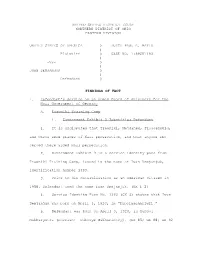

Findings of Facts (2002)

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF OHIO EASTERN DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ) JUDGE PAUL R. MATIA ) Plaintiff ) CASE NO. 1:99CV1193 ) -vs- ) ) JOHN DEMJANJUK ) ) Defendant ) FINDINGS OF FACT I. Defendant's Service as an Armed Guard of Prisoners for the Nazi Government of Germany A. Trawniki Training Camp i. Government Exhibit 3 Identifies Defendant 1. It is undisputed that Trawniki, Majdanek, Flossenbürg, and Okzow were places of Nazi persecution, and that anyone who served there aided Nazi persecution. 2. Government Exhibit 3 is a service identity pass from Trawniki Training Camp, issued in the name of Iwan Demjanjuk, identification number 1393. 3. Prior to his naturalization as an American citizen in 1958, Defendant used the name Iwan Demjanjuk. (GX 1-2) 4. Service Identity Pass No. 1393 (GX 3) states that Iwan Demjanjuk was born on April 3, 1920, in "Duboimachariwzi." 5. Defendant was born on April 3, 1920, in Dubovi Makharyntsi (Russian: Dubovye Makharintsy). (GX 85; GX 88; GX 92 at 1065, 1110; GX 93.1 at 25; GX 98 at 6831; Tr. at 444-45). 6. Service Identity Pass No. 1393 (GX 3) states that the name of Iwan Demjanjuk's father was Nikolai. 7. The name of Defendant's father was Mykola (Russian: Nikolai). (GX 85 at 12; GX 88; GX 92 at 1110; GX 98 at 6832; Tr. at 446). 8. Service Identity Pass No. 1393 (GX 3) states that Iwan Demjanjuk's nationality was Ukrainian. 9. Defendant is of Ukrainian national origin. (GX 1.2-1.6; GX 2.4; GX 85 at 19; GX 88; GX 92 at 1065). -

The Survivor's Hunt for Nazi Fugitives in Brazil: The

THE SURVIVOR’S HUNT FOR NAZI FUGITIVES IN BRAZIL: THE CASES OF FRANZ STANGL AND GUSTAV WAGNER IN THE CONTEXT OF INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE by Kyle Leland McLain A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of North Carolina at Charlotte in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Charlotte 2016 Approved by: ______________________________ Dr. Heather Perry ______________________________ Dr. Jürgen Buchenau ______________________________ Dr. John Cox ii ©2016 Kyle Leland McLain ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ABSTRACT KYLE LELAND MCLAIN. The survivor’s hunt for Nazi fugitives in Brazil: the cases of Franz Stangl and Gustav Wagner in the context of international justice (Under the direction of DR. HEATHER PERRY) On April 23, 1978, Brazilian authorities arrested Gustav Wagner, a former Nazi internationally wanted for his crimes committed during the Holocaust. Despite a confirming witness and petitions from West Germany, Israel, Poland and Austria, the Brazilian Supreme Court blocked Wagner’s extradition and released him in 1979. Earlier in 1967, Brazil extradited Wagner’s former commanding officer, Franz Stangl, who stood trial in West Germany, was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. These two particular cases present a paradox in the international hunt to bring Nazi war criminals to justice. They both had almost identical experiences during the war and their escape, yet opposite outcomes once arrested. Trials against war criminals, particularly in West Germany, yielded some successes, but many resulted in acquittals or light sentences. Some Jewish survivors sought extrajudicial means to see that Holocaust perpetrators received their due justice. Some resorted to violence, such as vigilante justice carried out by “Jewish vengeance squads.” In other cases, private survivor and Jewish organizations collaborated to acquire information, lobby diplomatic representatives and draw public attention to the fact that many Nazi war criminals were still at large.