From Poet's Aid to Courtier's Pastime: an Examination of the Shift in Visual Style and Sounding Function of Italian Viols During the Renaissance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 189.Pmd

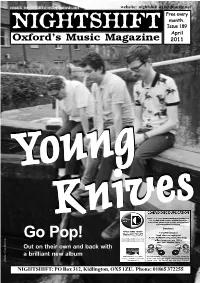

email: [email protected] NIGHTSHIFTwebsite: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every Oxford’s Music Magazine month. Issue 189 April 2011 YYYYYYoungoungoungoung KnivesKnivesKnivesKnives Go Pop! Out on their own and back with a brilliant new album photo: Cat Stevens NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net WILCO JOHNSON AND listings for the weekend, plus ticket DEACON BLUE are the latest details, are online at names added to this year’s www.oxfordjazzfestival.co.uk Cornbury Festival bill. The pair join already-announced headliners WITNEY MUSIC FESTIVAL returns James Blunt, The Faces and for its fifth annual run this month. Status Quo on a big-name bill that The festival runs from 24th April also includes Ray Davies, Cyndi through to 2nd May, featuring a Lauper, Bellowhead, Olly Murs, selection of mostly local acts across a GRUFF RHYS AND BELLOWHEAD have been announced as headliners The Like and Sophie Ellis-Bextor. dozen venues in the town. Amongst a at this year’s TRUCK FESTIVAL. Other new names on the bill are host of acts confirmed are Johnson For the first time Truck will run over three full days, over the weekend of prog-folksters Stackridge, Ben Smith and the Cadillac Blues Jam, 22nd-24th July at Hill Farm in Steventon. The festival will also enjoy an Montague & Pete Lawrie, Toy Phousa, Alice Messenger, Black Hats, increased capacity and the entire site has been redesigned to accommodate Hearts, Saint Jude and Jack Deer Chicago, Prohibition Smokers new stages. -

Jazz, Identity and Sound Design in a Melting Pot

ACADEMY OF MUSIC AND DRAMA Jazz, identity and sound design in a melting pot Lauri Kallio Independent Project (Degree Project), 15 HEC, Bachelor of Fine Arts in (Name of Program) Spring, 2019 Independent Project (Degree Project), 15 higher education credits Bachelor of Fine Arts in (Name of Program) Academy of Music and Drama, University of Gothenburg Spring, 2019 Author: Lauri Kallio Title: Jazz, identity and sound design in a melting pot Supervisor: Dr. Joel Eriksson Examiner: ABSTRACT In this piece of artistic research the author explores his musical toolbox and aesthetics for creating music. Finding compositional and music productional identity are also the main themes of this work. These aspects are being researched through the process creating new music. The author is also trying to build a bridge between his academic and informal studies over the years. The questions researched are about originality in composition and sound, and the challenges that occur during the working period. Key words: Jazz, Improvisation, Composition, Music Production, Ensemble, Free, Ambient 2 (34) Table of contents: 1. Introduction 1.1. Background 4 1.2. Goal and Questions 5 1.3. Method 6 2. Pre-recorded material 2.1.” 2147” 6 2.2. ”SAKIN” 7 2.3. ”BLE” 8 2.4. The selected elements 9 3. The compositions 3.1. “Mobile” 10 3.1.2. The rehearsing process 11 3.2. “ONEHE-274” 12 3.2.2. The rehearsing process 14 3.3. “TURBULENCE” 15 3.3.2. The rehearsing process 16 3.4. Rehearsing with electronics only 17 4. Conclusion 19 5. Afterword 20 6. -

Instruments and Their Music in the Middle Ages

Instruments and their Music in the Middle Ages Edited by Timothy J. McGee ASHGATE Contents Acknowledgements vii Series Preface xi Introduction xiii PART I CLASSIFICATIONS AND LISTS OF INSTRUMENTS 1 Edmund A. Bowles (1954), 'Haut and Bas: The Grouping of Musical Instruments in the Middle Ages', Musica Disciplina, 8, pp. 115—40. 3 2 Christopher Page (1982), 'German Musicians and Their Instruments: A 14th- century Account by Konrad of Megenberg', Early Music, 10, pp. 192-200. 29 3 Joscelyn Godwin (1977),'Mains divers acors\ Early Music, -5, pp. 148-59, [39-52], 39 4 Anthony Baines (1950), 'Fifteenth-Century Instruments in Tinctoris's De Inventione et Usu Musicae\ The Galpin Society Journal, 3, pp. 19-26. 53 5 Richard Rastall (1974), 'Some English Consort-Groupings of the Late Middle Ages', Music and Letters, 55, pp. 179-202. 61 PART II KEYBOARDS 6 Edmund A. Bowles (1966), 'On the Origin of the Keyboard Mechanism in the Late Middle Ages', Technology and Culture, 7, pp. 152-62. 87 7 Edwin M. Ripin (1975), 'Towards an Identification of the Chekker', The Galpin Society Journal, 28, pp. 11-25. 105 8 David Kinsela (1998), 'The Capture of the Chekker', The Galpin Society Journal, 51, pp. 64-85. 123 9 Edwin M. Ripin (1974), 'The Norrlanda Organ and the Ghent Altarpiece', in Gustaf Hillestrom_(ed.), Festschrift to Ernst Emsheimer, Studia instrumentorum musicae popularis, III, Stockholm: Nordiska Musikforlager, pp. 193-96, 286—88, [145-55]. 145 PART III PLUCKED STRINGS 10 Howard Mayer Brown (1983), 'The Trecento Harp', in Stanley Boorman (ed.), Studies in the Performance of Late Medieval Music, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. -

Cna85b2317313.Pdf

THE PAINTERS OF THE SCHOOL OF FERRARA BY EDMUND G. .GARDNER, M.A. AUTHOR OF "DUKES AND POETS IN FERRARA" "SAINT CATHERINE OF SIENA" ETC LONDON : DUCKWORTH AND CO. NEW YORK : CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS I DEDICATE THIS BOOK TO FRANK ROOKE LEY PREFACE Itf the following pages I have attempted to give a brief account of the famous school of painting that originated in Ferrara about the middle of the fifteenth century, and thence not only extended its influence to the other cities that owned the sway of the House of Este, but spread over all Emilia and Romagna, produced Correggio in Parma, and even shared in the making of Raphael at Urbino. Correggio himself is not included : he is too great a figure in Italian art to be treated as merely the member of a local school ; and he has already been the subject of a separate monograph in this series. The classical volumes of Girolamo Baruffaldi are still indispensable to the student of the artistic history of Ferrara. It was, however, Morelli who first revealed the importance and significance of the Perrarese school in the evolution of Italian art ; and, although a few of his conclusions and conjectures have to be abandoned or modified in the light of later researches and dis- coveries, his work must ever remain our starting-point. vii viii PREFACE The indefatigable researches of Signor Adolfo Venturi have covered almost every phase of the subject, and it would be impossible for any writer now treating of Perrarese painting to overstate the debt that he must inevitably owe to him. -

The Search for Consistent Intonation: an Exploration and Guide for Violoncellists

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2017 THE SEARCH FOR CONSISTENT INTONATION: AN EXPLORATION AND GUIDE FOR VIOLONCELLISTS Daniel Hoppe University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.380 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hoppe, Daniel, "THE SEARCH FOR CONSISTENT INTONATION: AN EXPLORATION AND GUIDE FOR VIOLONCELLISTS" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 98. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/98 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Enkelhedens Harmonik

Harmonikkens enkelhed - enkelhedens harmonik Droner og dronestrukturer i techno, metal rap og ny elektronisk fo lkemusik HENRIK MARSTAL 1. Forbemærkning Jo mere populærmusikvidenskaben igennem de seneste 15-20 år har etableret sig som en selvstændig gren af musikvidenskaben, jo mere har diskussionen af spørgsmålet vedrørende dens tilhørsforhold til den såkaldt traditionelle musikvidenskab optaget dens udøvere. Hvor nogle har søgt at søgt at opstille konstruktive modeller for hvordan de to bedst lader sig forene og gensidigt inspirere hinanden, l har andre adva ret mod at den traditionelle musikvidenskab metodisk influerer popu lærmusikvidenskaben. 2 Andre igen har direkte udtrykt mistillid til den traditionelle musikvidenskab, idet den af disse opfattes som værende konservativ, elitær og verdensfjern. 3 Derfor har populærmusikvidenska ben tilsyneladende kun en chance, nemlig at køre sit eget løb og ikke lade sig lokke ind i de blindgyder, som den traditionelle musikviden skab allerede befinder sig i. Der er ganske vist en række videnskabsteoretiske forhold der er funda mentalt anderledes for populærmusikken end for kunstmusikken. Og det er vigtigt at disse forhold til stadighed bliver diskuteret og betragtet som en del af den populærmusikvidenskabelige dagsorden. Men den ofte meget pointerede måde hvorpå det hidtil er blevet gjort, gør det nødvendigt samtidig at stille sig selv spørgsmålet: hvad vil populærmu sikvidenskaben egentlig - vil den virkelig gøre op med den mere tradi tionelle musikvidenskab ved at reformulere dens metoder og vokabula- 129 rium, eller vil den fortsætte i de mange forskellige retninger og spor, som den traditionelle musikvidenskab har afstukket? Vil den virkelig af skære kontakten med den musikvidenskab hvis udøvere af dens hårde ste kritikere betegnes som værende 'perverted by musical training' (McClary/Walser 1990:283), eller vil den på konstruktiv vis drage nyt te af musikvidenskabens store erfaring? Måske burde det slet ikke være nødvendigt at formulere den slags spørgsmål. -

Le Ray Au Soleyl

Le Ray au Soleyl Musica alla corte dei Visconti alla fine del XIV secolo B © fra bernardo,f Wien 2011 LE RAY AU SOLEYL Musica alla corte dei Visconti alla fine del XIV secolo «... quando un’anima riceve un’impressione di bellezza non sensibile non in modo astratto, ma attraverso un’impressione reale e diretta, come quella avvertita quando si percepisce un canto» Simone Weil «Il canto è un animale aereo» Marsilio Ficino Verso la CORTE Del CoNTE DI VIRTÙ, sulle orme DI PETrarCA Nell’ultimo trentennio del Trecento e nei primi anni del Quattrocento il medioevo splende come una foglia d’autunno che sta per cadere e rivela colori impredicibili e irripetibili poiché conseguenza della sua estate e non di altre. L’Ars nova sembra arrivare a una fase di incandescenza, di ebbrezza per gli incredibili conseguimenti notazionali, che si accompagnano a una perizia estrema nell’arte del contrappunto e a una padronanza dell’intenzione retorica che ancora oggi si è soliti concedere solo ad epoche assai posteriori. Eminente- mente in Francia e in Italia, fioriscono maestri che raffinano l’arte musicale conducendola a vette da cui è difficile immaginare di poter muovere un solo passo ulteriore. Essi infatti giungono alle soglie della modernità, si affacciano arditamente sul Tempo Nuovo, ma per morirvi quasi senza eredità. Le prime testimonianze che legano il nome dei Visconti alla musica e ai musicisti sono più antiche di qualche decennio rispetto a questa sta- gione ultima. Risalgono infatti al II quarto del XIV secolo e ai primi maestri dell’Ars nova italiana: in particolare a Maestro Piero, Giovanni da Cascia e Jacopo da Bologna. -

Adam DE LA HALLE Le Jeu De Robin Et De Marion

557337 bk Robin US 13/2/06 17:19 Page 12 1 Motet: Mout / Robins m’aime / PORTARE 1:03 Scene 3 Adam 2 Pilgrim’s Prologue after LI JUS DU PELERIN 2:46 ¢ Robin rounds up guests for the party. 1:54 ∞ Motet: Mout / Robins m’aime / PORTARE 1:02 DE LA HALLE LI GIEUS DE ROBIN ET DE MARION Scene 4 Scene 1 § The Knight returns to find his bird... 2:09 Marion is happily minding her own business... ¶ J’oi Robin flagoler (Marion) 0:21 Le Jeu de Robin et de Marion 3 Robins m’aime (Marion) 3:02 • ...beats up Robin and kidnaps Marion... 2:35 4 Je me repairoie (Knight) 0:39 ª Hé resveille toi Robin (Gautiers li Testus) 0:37 5 Hé Robin (Marion) 0:22 º ...but Robin is aroused to the point of valour. 1:03 TONUS PEREGRINUS 6 ...when along comes a Knight on the lookout... 4:33 ⁄ Rondeau III: Hareu 0:41 7 Vous perdés vo paine (Marion) 0:22 8 ...but Marion means no when she says so... 0:30 Scene 5 9 Bergeronnete sui (Marion) 0:22 ¤ Marion sees off the Knight, her friends roll up... 3:54 0 ...and the Knight leaves empty-handed. 0:12 ‹ Aveuc tele compaignie (tous) 1:01 ! Trairi deluriau (Marion + Knight) 2:07 › ...and it’s time for all kinds of party games. 10:21 @ Rondeau II: Li dous regars 1:04 # Rondeau XV: Tant con je vivrai 1:40 Scene 6 fi Robin rescues a sheep, declares his love... 4:54 Scene 2 fl J’ai encore un tel pasté (Robin) 0:29 Robin makes his way to Marion.. -

JAMES D. BABCOCK, MBA, CFA, CPA 191 South Salem Road Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 (203) 994-7244 [email protected]

JAMES D. BABCOCK, MBA, CFA, CPA 191 South Salem Road Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 (203) 994-7244 [email protected] List of Addendums First Addendum – Middle Ages Second Addendum – Modern and Modern Sub-Categories A. 20th Century B. 21st Century C. Modern and High Modern D. Postmodern and Contemporary E. Descrtiption of Categories (alphabetic) and Important Composers Third Addendum – Composers Fourth Addendum – Musical Terms and Concepts 1 First Addendum – Middle Ages A. The Early Medieval Music (500-1150). i. Early chant traditions Chant (or plainsong) is a monophonic sacred form which represents the earliest known music of the Christian Church. The simplest, syllabic chants, in which each syllable is set to one note, were probably intended to be sung by the choir or congregation, while the more florid, melismatic examples (which have many notes to each syllable) were probably performed by soloists. Plainchant melodies (which are sometimes referred to as a “drown,” are characterized by the following: A monophonic texture; For ease of singing, relatively conjunct melodic contour (meaning no large intervals between one note and the next) and a restricted range (no notes too high or too low); and Rhythms based strictly on the articulation of the word being sung (meaning no steady dancelike beats). Chant developed separately in several European centers, the most important being Rome, Hispania, Gaul, Milan and Ireland. Chant was developed to support the regional liturgies used when celebrating Mass. Each area developed its own chant and rules for celebration. In Spain and Portugal, Mozarabic chant was used, showing the influence of North Afgican music. The Mozarabic liturgy survived through Muslim rule, though this was an isolated strand and was later suppressed in an attempt to enforce conformity on the entire liturgy. -

Fomrhi Quarterly

Quarterly No. Ill, February 2009 FoMRHI Quarterly BULLETIN 111 Christopher Goodwin 2 COMMUNICATIONS 1835 Jan Steenbergen and his oboes Jan Bouterse 5 1836 Observations on glue and an early lute construction technique John Downing 16 1837 Thomas Stanesby Junior's 'True Concert Flute' Philippe Bolton 19 1838 Oil paintings of musical instruments - should we trust the Old Masters? Julian Goodacre 23 1839 A method of fixing loose soundbars Peter Bavington 24 1840 Mediaeval and Renaissance multiple tempo standards Ephraim Segerman 27 1841 The earliest soundposts Ephraim Segerman 36 1842 The historical basis of the modern early-music pitch standard ofa'=415Hz Ephraim Segerman 37 1843 Notes on the symphony Ephraim Segerman 41 1844 Some design considerations in making flattened lute backs Ephraim Segerman 45 1845 Tromba Marina notes Ian Allan 47 1846 Woodwinds dictionary online Mona Lemmel 54 1847 For information: Diderot et d'Alembert, L'Encyclopedie - free! John Downing 55 1848 'Mortua dolce cano' - a question John Downing 56 1849 Mortua dolce cano - two more instances Chris Goodwin 57 1850 Further to Comm. 1818, the new Mary Rose fiddle bow Jeremy Montagu 58 1851 Oud or lute? Comm. 1819 continued John Downing 59 1852 Wood fit for a king - a case of mistaken identity? Comm 1826 updated John Downing 62 1853 Reply to Segerman's Comm. 1830 John Downing 64 1854 Reply to John Catch's Comm 1827 on frets and temperaments Thomas Munck 65 1856 Re: Comms 1810 and 1815, Angled Bridges, Tapered Strings Frets and Bars Ephraim Segerman 66 1857 The lute in renaissance Spain: comment on Comm 1833 Ander Arroitajauregi 67 1858 Review of Modern Clavichord Studies: De Clavicordio VIII John Weston 68 The next issue, Quarterly 112, will appear in May 2009. -

Departement Künste, Medien, Philosophie Repertoireliste

Departement Künste, Medien, Philosophie Universität Basel, Musikwissenschaftliches Seminar, Petersgraben 27, CH-4051 Basel Repertoireliste Bachelorstudienfach Musikwissenschaft Die nachstehende Repertoireliste dient der Vorbereitung auf die Bachelorprüfung für Studierende, die ihr Studium im oder nach dem HS 2013 aufgenommen haben. Die Prüfungsordnung sieht vor, dass im Bereich der älteren wie auch der neueren Musik je eine Prüfungsfrage Repertoirekenntnisse behandelt. Zur Handhabung Die Repertoireliste setzt sich aus je 30 Werken der älteren und neueren Musikgeschichte zusammen, die – aus durchaus unterschiedlichen Gründen – als repräsentativ für musikhistorische Phänomene angesehen werden können. Da eine solche Zusammenstellung stets willkürlich erfolgt, ist jedes der unten aufgeführten Werke austauschbar und damit an individuelle Interessen und Kenntnisse der Studierenden anpassbar. Bedingung für Änderungen ist, dass die rechte Spalte (,Klassifizierung’) in Kombination mit der genannten Epoche für das gewählte Werk weiterhin erfüllt ist und die Gesamtzahl der Werke nicht verändert wird. So könnte beispielsweise in der Liste der Neueren Musik die unter Nr. 7 genannte Beethoven-Sinfonie durch eine Sinfonie Mozarts oder eines anderen Komponisten / einer anderen Komponistin dieser Zeit ersetzt werden, nicht aber durch eine Bruckner-Sinfonie oder ein Klavierkonzert Beethovens. Empfohlen wird, bereits in den ersten Semestern des Studiums mit der Abarbeiten der vorgeschlagenen bzw. dem Anlegen einer eigenen Liste zu beginnen. Durch die Kenntnis der je 30 Werke sollten die Studierenden (durch Hör- bzw. Notenstudium) in der Lage sein, allgemeinere Fragen zur Stilistik, Form oder zum musikgeschichtlichen Kontext der jeweiligen Werke beantworten zu können. Sämtliche Änderungsvorschläge müssen im Vorfeld natürlich rechtzeitig mit den Prüfenden abgesprochen werden. Universität Basel Musikwissenschaftliches Seminar Petersgraben 27 4051 Basel, Switzerland mws.unibas.ch i Repertoireliste Bachelor Musikwissenschaft Ältere Musik Nr. -

Filippino Lippi and Music

Filippino Lippi and Music Timothy J. McGee Trent University Un examen attentif des illustrations musicales dans deux tableaux de Filippino Lippi nous fait mieux comprendre les intentions du peintre. Dans le « Portrait d’un musicien », l’instrument tenu entre les mains du personnage, tout comme ceux représentés dans l’arrière-plan, renseigne au sujet du type de musique à être interprétée, et contribue ainsi à expliquer la présence de la citation de Pétrarque dans le tableau. Dans la « Madone et l’enfant avec les anges », la découverte d’une citation musicale sur le rouleau tenu par les anges musiciens suggère le propos du tableau. n addition to their value as art, paintings can also be an excellent source of in- Iformation about people, events, and customs of the past. They can supply clear details about matters that are known only vaguely from written accounts, or in some cases, otherwise not known at all. For the field of music history, paintings can be informative about a number of social practices surrounding the performance of music, such as where performances took place, who attended, who performed, and what were the usual combinations of voices and instruments—the kind of detail that is important for an understanding of the place of music in a society, but that is rarely mentioned in the written accounts. Paintings are a valuable source of information concerning details such as shape, exact number of strings, performing posture, and the like, especially when the painter was knowledgeable about instruments and performance practices,