Embodied Listening and the Music of Sigur Rós Peter Elsdon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 189.Pmd

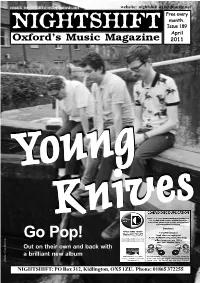

email: [email protected] NIGHTSHIFTwebsite: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every Oxford’s Music Magazine month. Issue 189 April 2011 YYYYYYoungoungoungoung KnivesKnivesKnivesKnives Go Pop! Out on their own and back with a brilliant new album photo: Cat Stevens NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net WILCO JOHNSON AND listings for the weekend, plus ticket DEACON BLUE are the latest details, are online at names added to this year’s www.oxfordjazzfestival.co.uk Cornbury Festival bill. The pair join already-announced headliners WITNEY MUSIC FESTIVAL returns James Blunt, The Faces and for its fifth annual run this month. Status Quo on a big-name bill that The festival runs from 24th April also includes Ray Davies, Cyndi through to 2nd May, featuring a Lauper, Bellowhead, Olly Murs, selection of mostly local acts across a GRUFF RHYS AND BELLOWHEAD have been announced as headliners The Like and Sophie Ellis-Bextor. dozen venues in the town. Amongst a at this year’s TRUCK FESTIVAL. Other new names on the bill are host of acts confirmed are Johnson For the first time Truck will run over three full days, over the weekend of prog-folksters Stackridge, Ben Smith and the Cadillac Blues Jam, 22nd-24th July at Hill Farm in Steventon. The festival will also enjoy an Montague & Pete Lawrie, Toy Phousa, Alice Messenger, Black Hats, increased capacity and the entire site has been redesigned to accommodate Hearts, Saint Jude and Jack Deer Chicago, Prohibition Smokers new stages. -

Volcanic Action and the Geosocial in Sigur Rós's “Brennisteinn”

Journal of Aesthetics & Culture ISSN: (Print) 2000-4214 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/zjac20 Musical aesthetics below ground: volcanic action and the geosocial in Sigur Rós’s “Brennisteinn” Tore Størvold To cite this article: Tore Størvold (2020) Musical aesthetics below ground: volcanic action and the geosocial in Sigur Rós’s “Brennisteinn”, Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, 12:1, 1761060, DOI: 10.1080/20004214.2020.1761060 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/20004214.2020.1761060 © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 04 May 2020. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=zjac20 JOURNAL OF AESTHETICS & CULTURE 2020, VOL. 12, 1761060 https://doi.org/10.1080/20004214.2020.1761060 Musical aesthetics below ground: volcanic action and the geosocial in Sigur Rós’s “Brennisteinn” Tore Størvold Department of Musicology, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This article presents a musicological and ecocritical close reading of the song “Brennisteinn” Sigur Rós; anthropocene; (“sulphur” or, literally, “burning rock”) by the acclaimed post-rock band Sigur Rós. The song— ecomusicology; ecocriticism; and its accompanying music video—features musical, lyrical, and audiovisual means of popular music; Iceland registering the turbulence of living in volcanic landscapes. My analysis of Sigur Rós’s music opens up a window into an Icelandic cultural history of inhabiting a risky Earth, a condition captured by anthropologist Gísli Pálsson’s concept of geosociality, which emerged from his ethnography in communities living with volcanoes. -

Jazz, Identity and Sound Design in a Melting Pot

ACADEMY OF MUSIC AND DRAMA Jazz, identity and sound design in a melting pot Lauri Kallio Independent Project (Degree Project), 15 HEC, Bachelor of Fine Arts in (Name of Program) Spring, 2019 Independent Project (Degree Project), 15 higher education credits Bachelor of Fine Arts in (Name of Program) Academy of Music and Drama, University of Gothenburg Spring, 2019 Author: Lauri Kallio Title: Jazz, identity and sound design in a melting pot Supervisor: Dr. Joel Eriksson Examiner: ABSTRACT In this piece of artistic research the author explores his musical toolbox and aesthetics for creating music. Finding compositional and music productional identity are also the main themes of this work. These aspects are being researched through the process creating new music. The author is also trying to build a bridge between his academic and informal studies over the years. The questions researched are about originality in composition and sound, and the challenges that occur during the working period. Key words: Jazz, Improvisation, Composition, Music Production, Ensemble, Free, Ambient 2 (34) Table of contents: 1. Introduction 1.1. Background 4 1.2. Goal and Questions 5 1.3. Method 6 2. Pre-recorded material 2.1.” 2147” 6 2.2. ”SAKIN” 7 2.3. ”BLE” 8 2.4. The selected elements 9 3. The compositions 3.1. “Mobile” 10 3.1.2. The rehearsing process 11 3.2. “ONEHE-274” 12 3.2.2. The rehearsing process 14 3.3. “TURBULENCE” 15 3.3.2. The rehearsing process 16 3.4. Rehearsing with electronics only 17 4. Conclusion 19 5. Afterword 20 6. -

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED the CRITICAL RECEPTION of INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY in EUROPE, C. 1815 A

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Zarko Cvejic August 2011 © 2011 Zarko Cvejic THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 Zarko Cvejic, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 The purpose of this dissertation is to offer a novel reading of the steady decline that instrumental virtuosity underwent in its critical reception between c. 1815 and c. 1850, represented here by a selection of the most influential music periodicals edited in Europe at that time. In contemporary philosophy, the same period saw, on the one hand, the reconceptualization of music (especially of instrumental music) from ―pleasant nonsense‖ (Sulzer) and a merely ―agreeable art‖ (Kant) into the ―most romantic of the arts‖ (E. T. A. Hoffmann), a radically disembodied, aesthetically autonomous, and transcendent art and on the other, the growing suspicion about the tenability of the free subject of the Enlightenment. This dissertation‘s main claim is that those three developments did not merely coincide but, rather, that the changes in the aesthetics of music and the philosophy of subjectivity around 1800 made a deep impact on the contemporary critical reception of instrumental virtuosity. More precisely, it seems that instrumental virtuosity was increasingly regarded with suspicion because it was deemed incompatible with, and even threatening to, the new philosophic conception of music and via it, to the increasingly beleaguered notion of subjective freedom that music thus reconceived was meant to symbolize. -

The Sound of Ruins: Sigur Rós' Heima and the Post

CURRENT ISSUE ARCHIVE ABOUT EDITORIAL BOARD ADVISORY BOARD CALL FOR PAPERS SUBMISSION GUIDELINES CONTACT Share This Article The Sound of Ruins: Sigur Rós’ Heima and the Post-Rock Elegy for Place ABOUT INTERFERENCE View As PDF By Lawson Fletcher Interference is a biannual online journal in association w ith the Graduate School of Creative Arts and Media (Gradcam). It is an open access forum on the role of sound in Abstract cultural practices, providing a trans- disciplinary platform for the presentation of research and practice in areas such as Amongst the ways in which it maps out the geographical imagination of place, music plays a unique acoustic ecology, sensory anthropology, role in the formation and reformation of spatial memories, connecting to and reviving alternative sonic arts, musicology, technology studies times and places latent within a particular environment. Post-rock epitomises this: understood as a and philosophy. The journal seeks to balance kind of negative space, the genre acts as an elegy for and symbolic reconstruction of the spatial its content betw een scholarly w riting, erasures of late capitalism. After outlining how post-rock’s accommodation of urban atmosphere accounts of creative practice, and an active into its sonic textures enables an ‘auditory drift’ that orients listeners to the city’s fragments, the engagement w ith current research topics in article’s first case study considers how formative Canadian post-rock acts develop this concrete audio culture. [ More ] practice into the musical staging of urban ruin. Turning to Sigur Rós, the article challenges the assumption that this Icelandic quartet’s music simply evokes the untouched natural beauty of their CALL FOR PAPERS homeland, through a critical reading of the 2007 tour documentary Heima. -

The Search for Consistent Intonation: an Exploration and Guide for Violoncellists

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2017 THE SEARCH FOR CONSISTENT INTONATION: AN EXPLORATION AND GUIDE FOR VIOLONCELLISTS Daniel Hoppe University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.380 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hoppe, Daniel, "THE SEARCH FOR CONSISTENT INTONATION: AN EXPLORATION AND GUIDE FOR VIOLONCELLISTS" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 98. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/98 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Harvest Records Discography

Harvest Records Discography Capitol 100 series SKAO 314 - Quatermass - QUATERMASS [1970] Entropy/Black Sheep Of The Family/Post War Saturday Echo/Good Lord Knows/Up On The Ground//Gemini/Make Up Your Mind/Laughin’ Tackle/Entropy (Reprise) SKAO 351 - Horizons - The GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH [1970] Again And Again/Angelina/Day Of The Lady/Horizons/I Fought For Love/Real Cool World/Skylight Man/Sunflower Morning [*] ST 370 - Anthems In Eden - SHIRLEY & DOROTHY COLLINS [1969] Awakening-Whitesun Dance/Beginning/Bonny Cuckoo/Ca’ The Yowes/Courtship-Wedding Song/Denying- Blacksmith/Dream-Lowlands/Foresaking-Our Captain Cried/Gathering Rushes In The Month Of May/God Dog/Gower Wassail/Leavetaking-Pleasant And Delightful/Meeting-Searching For Lambs/Nellie/New Beginning-Staines Morris/Ramble Away [*] ST 371 - Wasa Wasa - The EDGAR BROUGHTON BAND [1969] Death Of An Electric Citizen/American Body Soldier/Why Can’t Somebody Love You/Neptune/Evil//Crying/Love In The Rain/Dawn Crept Away ST 376 - Alchemy - THIRD EAR BAND [1969] Area Three/Dragon Lines/Druid One/Egyptian Book Of The Dead/Ghetto Raga/Lark Rise/Mosaic/Stone Circle [*] SKAO 382 - Atom Heart Mother - The PINK FLOYD [1970] Atom Heart Mother Suite (Father’s Shout-Breast Milky-Mother Fore-Funky Dung-Mind Your Throats Please- Remergence)//If/Summer ’68/Fat Old Sun/Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast (Rise And Shine-Sunny Side Up- Morning Glory) SKAO 387 - Panama Limited Jug Band - PANAMA LIMITED JUG BAND [1969] Canned Heat/Cocaine Habit/Don’t You Ease Me In/Going To Germany/Railroad/Rich Girl/Sundown/38 -

Stan Magazynu Caĺ†Oĺıäƒ Lp Cd Sacd Akcesoria.Xls

CENA WYKONAWCA/TYTUŁ BRUTTO NOŚNIK DOSTAWCA ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - AT FILLMORE EAST 159,99 SACD BERTUS ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - AT FILLMORE EAST (NUMBERED 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - BROTHERS AND SISTERS (NUMBE 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - EAT A PEACH (NUMBERED LIMIT 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - IDLEWILD SOUTH (GOLD CD) 129,99 CD GOLD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - THE ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND (N 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ASIA - ASIA 179,99 SACD BERTUS BAND - STAGE FRIGHT (HYBRID SACD) 89,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BAND, THE - MUSIC FROM BIG PINK (NUMBERED LIMITED 89,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BAND, THE - THE LAST WALTZ (NUMBERED LIMITED EDITI 179,99 2 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BASIE, COUNT - LIVE AT THE SANDS: BEFORE FRANK (N 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BIBB, ERIC - BLUES, BALLADS & WORK SONGS 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC - JUST LIKE LOVE 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC - RAINBOW PEOPLE 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC & NEEDED TIME - GOOD STUFF 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC & NEEDED TIME - SPIRIT & THE BLUES 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BLIND FAITH - BLIND FAITH 159,99 SACD BERTUS BOTTLENECK, JOHN - ALL AROUND MAN 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 CAMEL - RAIN DANCES 139,99 SHMCD BERTUS CAMEL - SNOW GOOSE 99,99 SHMCD BERTUS CARAVAN - IN THE LAND OF GREY AND PINK 159,99 SACD BERTUS CARS - HEARTBEAT CITY (NUMBERED LIMITED EDITION HY 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY CHARLES, RAY - THE GENIUS AFTER HOURS (NUMBERED LI 99,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY CHARLES, RAY - THE GENIUS OF RAY CHARLES (NUMBERED 129,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY -

Ron Geesin Music from the Body Mp3, Flac, Wma

Ron Geesin Music From The Body mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock Album: Music From The Body Country: UK Style: Musique Concrète, Avantgarde MP3 version RAR size: 1682 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1495 mb WMA version RAR size: 1953 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 599 Other Formats: AC3 WMA MMF RA MP1 MIDI MOD Tracklist A1 Our Song A2 Sea Shell And Stone A3 Red Stuff Writhe A4 A Gentle Breeze Blew Through Life A5 Lick Your Partners A6 Bridge Passage For Three Plastic Teeth A7 Chain Of Life A8 The Womb Bit A9 Embryo Thought A10 March Past Of The Embryos A11 More Than Seven Dwarfs In Penis-Land A12 Dance Of The Red Corpuscles B1 Body Transport B2 Hand Dance - Full Evening Dress B3 Breathe B4 Old Folks Ascension B5 Bed-Time-Dream-Clime B6 Piddle In Perspex B7 Embryonic Womb-Walk B8 Mrs. Throat Goes Walking B9 Sea Shell And Soft Stone B10 Give Birth To A Smile Notes Blue translucent cassette. Also released with a clear/foil style cassette. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Ron Geesin & Roger Ron Geesin SHSP 4008, 1E Waters - Music From Harvest, SHSP 4008, 1E & Roger UK 1970 062 o 04615 The Body (LP, EMI 062 o 04615 Waters Album) Ron Geesin & Roger Ron Geesin SHSP 4008, 1E Waters - Music From Harvest, SHSP 4008, 1E & Roger UK Unknown 062 o 04615 The Body (LP, EMI 062 o 04615 Waters Album, RE) Ron Geesin & Roger Ron Geesin Waters - Music From Import IMP 1002 & Roger IMP 1002 US 1976 The Body (LP, Records Waters Album, RE) Ron Geesin & Roger Ron Geesin SHVL-4008, Waters - Music From Harvest, -

Atom Heart Mother Est Une Oeuvre Singulière Qu'on a Qualifiée D'énigme : Existe-T-Il Un Rapport Entre Le Titre, La Pochette

Atom Heart Mother est une oeuvre singulière qu'on a qualifiée d'énigme : existe-t-il un rapport entre le titre, la pochette, et la musique ? Titre-pochette : lait (voir ci-dessous la magnifique version des élèves du CNSM de Paris), pochette-musique : vache des westerns ? … Finalement, il n'y a sans doute rien à expliquer. Le compositeur Ron Geesin dit d'ailleurs apprécier l'absurdité, et être influencé par le surréalisme (voir « les cadavres exquis ). Le rapport titre-pochette-musique m'évoque un cadavre exquis. Le rock progressif anglais se dit influencé par le surréalisme. de Patchwork : « Cet album était un patchwork confus » (David Gilmour). Effectivement, les pièces mises bout à bout n'ont pas forcément de rapport entre elles, si ce n'est un fil conducteur de mi mineur. d'oeuvre charnière, charnière entre la musique savante et la musique populaire, mais charnière aussi dans la carrière du groupe entre l'héritage pop des Beatles et le sommet en mars 1973, avec l'album The Dark Side of the Moon qui restera plus de 14 ans dans le top 200 (record absolu) et le 3e album le plus vendu au monde, album dans lequel le séquenceur fait son apparition. d'Odyssée (terme employé par Roger Waters) ou de poème symphonique avec 6 parties dont les titres forment une sorte de lien : Father's Shout , Breast Milky , Mother Fore, Funky Dung Mind your Throats Please , Remergence. Le mouvement Rock est issu du blues. Le premier succès mondial du rock'n'roll est Rock around the Clock de Bill Haley en 1954 aux USA. -

Effect of Transcutaneous Spinal Cord Stimulation on Spasticity, Mobility, Pain and Sleep in Community Dwelling Individuals Post-Stroke

Effect of Transcutaneous Spinal Cord Stimulation on Spasticity, Mobility, Pain and Sleep in Community Dwelling Individuals Post-Stroke A single case withdrawal design Belinda Chenery Thesis for the degree of Master of Science in Movement Science June 2019 Effect of Transcutaneous Spinal Cord Stimulation on Spasticity, Mobility, Pain and Sleep in Community Dwelling Individuals Post-Stroke A single case withdrawal design Belinda Chenery Thesis for the degree of Master of Science in Movement Science Number of credits: 60 ECTS Supervisor: Anestis Divanoglou Masters committee: Anestis Divanoglou, Kristín Briem, Þórður Helgason Department of Physical Therapy Faculty of Medicine School of Health Sciences June 2019 Áhrif raförvunar mænu með yfirborðsskautum á síspennu, hreyfigetu, verki og svefn einstaklinga sem hafa fengið heilaslag og búa heima Einliðavendisnið Belinda Chenery Ritgerð til meistaragráðu í hreyfivísindum Fjöldi eininga: 60 ECTS Umsjónarkennari: Anestis Divanoglou Meistaranámsnefnd: Anestis Divanoglou, Kristín Briem, Þórður Helgason Námsbraut í sjúkraþjálfun Læknadeild Heilbrigðisvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands Júní 2019 Thesis for master’s degree in Physiotherapy at the University of Iceland. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the prior permission of the copyright holder. © Belinda Chenery, 2019 Prentun: Háskólaprent Reykjavík, Ísland, 2019 Abstract Effective treatment modalities for alleviating spasticity and pain and enhancing mobility and sleep are limited post-stroke. Some evidence suggests that techniques of transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation (tSCS) may be beneficial. However, these are typically small pretest-posttest studies with high risk of bias. To date, there are no studies that evaluate the effects of tSCS in stroke. The aim of the current study was to evaluate the effects of daily home-treatment with tSCS on spasticity, mobility, pain and sleep in community dwelling individuals post-stroke. -

Nycemf 2021 Program Book

NEW YORK CITY ELECTROACOUSTIC MUSIC FESTIVAL __ VIRTUAL ONLINE FESTIVAL __ www.nycemf.org CONTENTS DIRECTOR’S WELCOME 3 STEERING COMMITTEE 3 REVIEWING 6 PAPERS 7 WORKSHOPS 9 CONCERTS 10 INSTALLATIONS 51 BIOGRAPHIES 53 DIRECTOR’S NYCEMF 2021 WELCOME STEERING COMMITTEE Welcome to NYCEMF 2021. After a year of having Ioannis Andriotis, composer and audio engineer. virtually all live music in New York City and elsewhere https://www.andriotismusic.com/ completely shut down due to the coronavirus pandemic, we decided that we still wanted to provide an outlet to all Angelo Bello, composer. https://angelobello.net the composers who have continued to write music during this time. That is why we decided to plan another virtual Nathan Bowen, composer, Professor at Moorpark electroacoustic music festival for this year. Last year, College (http://nb23.com/blog/) after having planned a live festival, we had to cancel it and put on everything virtually; this year, we planned to George Brunner, composer, Director of Music go virtual from the start. We hope to be able to resume Technology, Brooklyn College C.U.N.Y. our live concerts in 2022. Daniel Fine, composer, New York City The limitations of a virtual festival meant that we could plan only to do events that could be done through the Travis Garrison, composer, Music Technology faculty at internet. Only stereo music could be played, and only the University of Central Missouri online installations could work. Paper sessions and (http://www.travisgarrison.com) workshops could be done through applications like zoom. We hope to be able to do all of these things in Doug Geers, composer, Professor of Music at Brooklyn person next year, and to resume concerts in full surround College sound.