Dublin City Parks Strategy 2019 - 2022

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Notes and Comments

Some Notes and Comments AGM of the Association The AGM took place on the 12 th April 2013. There was a good attendance of members. Reports from the chairman, secretary, treasurer environment and planning officer were presented and a new committee was elected for the coming year. No 52 June 2013 The formal meeting was followed by members question time. Issues raised were -the lack of proper pedestrian facilities in Rathgar, the new A view from the Chairman John McCarthy property tax, planning issues and enforcement, the state of pavements after last Autumn’s leaf fall and the continuing problem of dog fouling. It is that time of year when we should be out enjoying our gardens, our leafy suburbs, linear parks and river banks. However with very poor weather we are Annual Garden Competition limited in what we can do. Having that said, we have to make the effort toget up The judging of front gardens in the Rathgar area will be conducted in late and get on with living. June with the presentation of the Dixon cup for best garden taking place at the Rathgar Horticultural Society’s annual show in early July Spring this year, brought the Local Property Tax demands. Whilst we can argue the unfairness of it, this tax is here to stay. At a recent meeting in Rathmines, Design Manual for Urban Roads . This is the title of a new publication by local TDs Lucinda Creighton, Ruairi Quinn and Kevin Humphries stated that the Departments of Transport and Environment. This is a welcome 80% of the LPT will go into the coffers of the local council. -

'Dublin's North Inner City, Preservationism and Irish Modernity in the 1960S'

Edinburgh Research Explorer Dublin’s North Inner City, Preservationism and Irish Modernity in the 1960s Citation for published version: Hanna, E 2010, 'Dublin’s North Inner City, Preservationism and Irish Modernity in the 1960s', Historical Journal, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 1015-1035. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X10000464 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1017/S0018246X10000464 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Historical Journal Publisher Rights Statement: © Hanna, E. (2010). Dublin’s North Inner City, Preservationism and Irish Modernity in the 1960s. Historical Journal, 53(4), 1015-1035doi: 10.1017/S0018246X10000464 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 The Historical Journal http://journals.cambridge.org/HIS Additional services for The Historical Journal: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here DUBLIN'S NORTH INNER CITY, PRESERVATIONISM, AND IRISH MODERNITY IN THE 1960S ERIKA HANNA The Historical Journal / Volume 53 / Issue 04 / December 2010, pp 1015 - 1035 DOI: 10.1017/S0018246X10000464, Published online: 03 November 2010 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0018246X10000464 How to cite this article: ERIKA HANNA (2010). -

OPW Heritage Trade Catalogue 2021-2022 Dublin

heritage ireland Ireland’s National Heritage in the care of the 0ffice 2019 of public works Admission Charges Apply in 2022 Trade Catalogue 2021-2022 Dublin Ireland’s Ancient East Ireland’s Hidden Heartlands Wild Atlantic Way group trade information 1. groups and trade … explore more ¬ Specific language audio-visual films in some sites for pre-booked tours Bring your group to visit an historic place for a great day out. ¬ If you are a public group or in the travel trade and have ¬ Access to OPW Tour Operator Voucher Scheme (TOVS). customers for group travel, FIT or MICE our staff are Payment by monthly invoice. delighted to present memorable experiences at over 70 Email us at [email protected] historic attractions.* * Minimum numbers may vary at sites due to COVID–19 restrictions as at April 2021. ¬ Our guides excel in customer service and storytelling * Some sites may not be fully accessible or closed due to COVID–19 that enthrals and engrosses the visitor, while offering restrictions as at April 2021. a unique insight into the extraordinary legacy of Ireland’s iconic heritage. 3. plan your itinerary ¬ Join our mailing list for more information on heritageireland.ie ¬ For inspiration about passage tombs, historic castles, ¬ Contact each site directly for booking – details in Groups / Christian sites and historic houses and gardens throughout Trade Catalogue Ireland. * Due to COVID–19 restrictions some sites may not be open. ¬ From brunch to banquets – find out about catering facilities at sites, events and more … 2. group visit benefits ¬ Wild Atlantic Way ¬ Group Rate – up to 20% off normal adult admission rate. -

Heritage Council Annual Report 2014

Annual Report 2014 www.heritagecouncil.ie CONTENTS © The Heritage Council 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be printed or reproduced or utilised in any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or heretoafter invented, including photocopying or licence permitting restricted copying in Ireland issued by the Irish Copyright Licencing Agency Ltd., The Writers Centre, 19 Parnell Square, Dublin 1 Published by the Heritage Council CHAIRMAN’S WELCOME 2 The Heritage Council of Ireland Series CHIEF EXECUTIVE’S REPORT 2014 3 ISBN 978-1-906304-30-0 HERITAGE COUNCIL BOARD MEMBERS AND STAFF 2014 5 THE HERITAGE COUNCIL – 2014 IN FIGURES 6 The Heritage Council is extremely grateful to the following organisations and individuals for supplying additional photographs, images and diagrams used in the Annual Report 2014: 1 BACKGROUND TO HERITAGE & THE HERITAGE COUNCIL – STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES, RESOURCES AND SUSTAINABILITY SUSTAINABILITY 8 Andrew Power (Heritage Week), Birdwatch Ireland, Burrenbeo Trust (Dr. Brendan Dunford), Brady Shipman Martin, Clare Keogh (Cork City Council), Clive Wasson Photography (Donegal), David Jordan (Co. Carlow), Europa Nostra, the Irish Planning Institute (IPI), Kilkenny Tourism, 2 OUR PERFORMANCE IN 2014 – NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL AWARDS RECEIVED BY THE HERITAGE COUNCIL 20 Dr. Liam Lysaght (Director, National Biodiversity Data Centre), Michael Martin (Co. Carlow), Michael Scully (Laois), Valerie O’Sullivan Photography (Co. Kerry), Pat Moore (Co. Kilkenny) and The Paul Hogarth Company (Belfast and Dublin). 3 2014 KEY HIGHLIGHTS – POLICY ADVICE, PROGRAMMES AND PROJECTS 24 Images used on pages 20, 30, 64 and 82 © Photographic Unit, National Monuments Service 4 SUPPORTING EMPLOYMENT AND JOB CREATION (HC OBJECTIVE NO. -

UCD Commuting Guide

University College Dublin An Coláiste Ollscoile, Baile Átha Cliath CAMPUS COMMUTING GUIDE Belfield 2015/16 Commuting Check your by Bus (see overleaf for Belfield bus map) UCD Real Time Passenger Information Displays Route to ArrivED • N11 bus stop • Internal campus bus stops • Outside UCD James Joyce Library Campus • In UCD O’Brien Centre for Science Arriving autumn ‘15 using • Outside UCD Student Centre Increased UCD Services Public ArrivED • UCD now designated a terminus for x route buses (direct buses at peak times) • Increased services on 17, 142 and 145 routes serving the campus Transport • UCD-DART shuttle bus to Sydney Parade during term time Arriving autumn ‘15 • UCD-LUAS shuttle bus to Windy Arbour on the LUAS Green Line during Transport for Ireland term time Transport for Ireland (www.transportforireland.ie) Dublin Bus Commuter App helps you plan journeys, door-to-door, anywhere in ArrivED Ireland, using public transport and/or walking. • Download Dublin Bus Live app for updates on arriving buses Hit the Road Don’t forget UCD operates a Taxsaver Travel Pass Scheme for staff commuting by Bus, Dart, LUAS and Rail. Hit the Road (www.hittheroad.ie) shows you how to get between any two points in Dublin City, using a smart Visit www.ucd.ie/hr for details. combination of Dublin Bus, LUAS and DART routes. Commuting Commuting by Bike/on Foot by Car Improvements to UCD Cycling & Walking Facilities Parking is limited on campus and available on a first come first served basis exclusively for persons with business in UCD. Arrived All car parks are designated either permit parking or hourly paid. -

Representative Church Body Library, Dublin Ms

1 REPRESENTATIVE CHURCH BODY LIBRARY, DUBLIN MS 624 The records of the Young Women's Christian Association in Ireland (YWCA) including minute books and correspondence of the executive council, standing committee, several divisional councils and specific committees. 1885-2007 As well as general administrative material such as minutes, accounts and correspondence, the collection also includes memorabilia including leaflets, tracts, prayer cards and orders of service for special events giving colour to the organisation’s history. Topics covered include its early training home for missionaries; the national annual conference and annual sale; the development of the Dublin Bible College in the 1940s and early 1950s; and the development of camps activities for young people, boarding hostels and homes for workers throughout the island under both central and local branch control. Extensive materials also record the history of specific branches, hostels, houses and holiday homes, including Queen Mary Home, Belfast, the Baggot Street Hostel and the Radcliff Hall, Dublin, as well as the business and share- holding records of the YWCA Trust Corporation which managed YWCA properties. The collection is organised into 13 record groups, listed on pages 2 and 3 below. All of the material is open to the public with the exception of those items marked [CLOSED] for which the permission of the Board of the YWCA in Ireland, must first be obtained in writing, before access will be granted. From YWCA, Bray, deposited by Mrs Daphne Murphy, 1998; and YWCA headquarters, Dublin, 2012. 2 Arrangement 1. Minutes of the central administrative organisation (including the Executive Council, the General Council, the Irish Divisional Council, and the Standing Committee). -

M E R R I O N R O W D U B L I

MERRION ROW DUBLIN 2 Prime offices to let in Dublin’s most sought after location. 3 Description 2-4 Merrion Row offers occupiers a rare opportunity to locate in Dublin’s vibrant city centre. The building has been extensively refurbished throughout to provide stylish, high quality workspace over four floors, extending to a total NIA of 1,044.05 sq.m. (11,238 sq.ft.). Occupiers will benefit from the exceptional new open plan accommodation, completed to full third generation specification. A bright, contemporary reception with featured glass entrance sets the tone for the quality of finish delivered throughout. 4 5 Location Facebook Capita Google William Fry Accenture Bord Gáis Merrion Row, located in the Shire Pharmaceuticals Merrion Square hub of Dublin’s Business National Gallery ESB Headquarters Community, adjacent to of Ireland Government Natural History Buildings Government buildings and Museum National Library Trinity College The Merrion Hotel minutes from many well National Museum Fitzwilliam Square of Ireland established occupiers. Hudson Advisors Shelbourne Hotel Emirates The area is already home to many Intercom Aralez Pharmaceuticals leading occupiers across all sectors, Davy Stockbrokers including financial services, technology, MERRION Permanent TSB ROW media, insurance and banking. A sample AerCap of neighbouring occupiers includes The Conrad Hotel Hedgeserv Government Buildings, Shire Pharma, Grafton Street Stephen's Green St Stephen’s Green Intercom, AerCap, KPMG, PTSB, Emirates, Shopping Centre Maples & Calder The National Sky Aviation and Aralez Pharma. Department Concert Hall The Fitzwilliam Hotel The Gaiety Theatre of Foreign Affairs 2 – 4 Merrion Row benefits from Royal College Standard Life Ireland unrivalled access to public transport and Qualtrics Ireland of Surgeons of Ireland an excellent choice of amenities on the Indeed Sky Aviation doorstep, including St. -

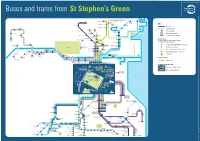

Buses and Trams from St Stephen's Green

142 Buses and trams from St Stephen’s Green 142 continues to Waterside, Seabury, Malahide, 32x continues to 41x Broomfield, Hazelbrook, Sainthelens and 15 Portmarnock, Swords Manor Portmarnock Sand’s Hotel Baldoyle Malahide and 142 Poppintree 140 Clongriffin Seabury Barrysparks Finglas IKEA KEY Charlestown SWORDS Main Street Ellenfield Park Darndale Beaumont Bus route Fosterstown (Boroimhe) Collinstown 14 Coolock North Blakestown (Intel) 11 44 Whitehall Bull Tram (Luas) line Wadelai Park Larkhill Island Finglas Road Collins Avenue Principal stop Donnycarney St Anne’s Park 7b Bus route terminus Maynooth Ballymun and Gardens (DCU) Easton Glasnevin Cemetery Whitehall Marino Tram (Luas) line terminus Glasnevin Dublin (Mobhi) Harbour Maynooth St Patrick’s Fairview Transfer Points (Kingsbury) Prussia Street 66x Phibsboro Locations where it is possible to change Drumcondra North Strand to a different form of transport Leixlip Mountjoy Square Rail (DART, COMMUTER or Intercity) Salesian College 7b 7d 46e Mater Connolly/ 67x Phoenix Park Busáras (Infirmary Road Tram (Luas Red line) Phoenix Park and Zoo) 46a Parnell Square 116 Lucan Road Gardiner Bus coach (regional or intercity) (Liffey Valley) Palmerstown Street Backweston O’Connell Street Lucan Village Esker Hill Abbey Street Park & Ride (larger car parks) Lower Ballyoulster North Wall/Beckett Bridge Ferry Port Lucan Chapelizod (142 Outbound stop only) Dodsboro Bypass Dublin Port Aghards 25x Islandbridge Heuston Celbridge Points of Interest Grand Canal Dock 15a 15b 145 Public Park Heuston Arran/Usher’s -

Irish Marriages, Being an Index to the Marriages in Walker's Hibernian

— .3-rfeb Marriages _ BBING AN' INDEX TO THE MARRIAGES IN Walker's Hibernian Magazine 1771 to 1812 WITH AN APPENDIX From the Notes cf Sir Arthur Vicars, f.s.a., Ulster King of Arms, of the Births, Marriages, and Deaths in the Anthologia Hibernica, 1793 and 1794 HENRY FARRAR VOL. II, K 7, and Appendix. ISSUED TO SUBSCRIBERS BY PHILLIMORE & CO., 36, ESSEX STREET, LONDON, [897. www.genespdf.com www.genespdf.com 1729519 3nK* ^ 3 n0# (Tfiarriages 177.1—1812. www.genespdf.com www.genespdf.com Seventy-five Copies only of this work printed, of u Inch this No. liS O&CLA^CV www.genespdf.com www.genespdf.com 1 INDEX TO THE IRISH MARRIAGES Walker's Hibernian Magazine, 1 771 —-1812. Kane, Lt.-col., Waterford Militia = Morgan, Miss, s. of Col., of Bircligrove, Glamorganshire Dec. 181 636 ,, Clair, Jiggmont, co.Cavan = Scott, Mrs., r. of Capt., d. of Mr, Sampson, of co. Fermanagh Aug. 17S5 448 ,, Mary = McKee, Francis 1S04 192 ,, Lt.-col. Nathan, late of 14th Foot = Nesbit, Miss, s. of Matt., of Derrycarr, co. Leitrim Dec. 1802 764 Kathcrens, Miss=He\vison, Henry 1772 112 Kavanagh, Miss = Archbold, Jas. 17S2 504 „ Miss = Cloney, Mr. 1772 336 ,, Catherine = Lannegan, Jas. 1777 704 ,, Catherine = Kavanagh, Edm. 1782 16S ,, Edmund, BalIincolon = Kavanagh, Cath., both of co. Carlow Alar. 1782 168 ,, Patrick = Nowlan, Miss May 1791 480 ,, Rhd., Mountjoy Sq. = Archbold, Miss, Usher's Quay Jan. 1S05 62 Kavenagh, Miss = Kavena"gh, Arthur 17S6 616 ,, Arthur, Coolnamarra, co. Carlow = Kavenagh, Miss, d. of Felix Nov. 17S6 616 Kaye, John Lyster, of Grange = Grey, Lady Amelia, y. -

Agenda Document for Central Area Committee, 10/07/2018 10:00

NOTIFICATION TO ATTEND MEETING OF THE CENTRAL AREA COMMITTEE TO BE HELD IN THE COUNCIL CHAMBER, CITY HALL, DAME STREET, DUBLIN 2. ON TUESDAY 10 JULY 2018 AT 10.00 AM AGENDA TUESDAY 10 JULY 2018 PAGE 1 With reference to the election of Chairperson 2 With reference to the election of Vice-Chairperson 3 With reference to the minutes of the Central Area Committee meeting held on 12 3 - 8 June, 2018 4 Questions to the Area Manager 9 - 14 5 With reference to a presentation by Dublin Docklands 6 With reference to the proposed grant of a further licence of Kiosks 1 & 2, Liffey 15 - 18 Boardwalk, Dublin 1. 7 With reference to Planning criteria for domestic extensions 19 - 26 8 With reference to the minutes of the Traffic Advisory Group held on 26th June, 27 - 38 2018 9 With reference to a proposal to initiate the procedure for the Extinguishment of the 39 - 40 Public Right of Way over Wellington Place North, Dublin 7 10 With reference to an update on the Public Domain Unit 41 - 44 11 With reference to an update on Housing Matters in the North West and North East 45 - 64 Inner City. 12 With reference to an update on the North East Inner City Programme 65 - 76 13 With reference to updates on the following: Central Area Sports, Grangegorman 77 - 90 Development and Central Area Age friendly 14 With reference to Motions to the Area Manager 91 - 92 MINUTES OF THE CENTRAL AREA COMMITTEE MEETING HELD ON TUESDAY 12 JUNE 2018 1 With reference to the minutes of the Central Area Committee meeting held on 8th May, 2018 ORDER: Agreed. -

Fitzwilliam Hall, Fitzwilliam Place, Dublin, Ireland

Fitzwilliam Hall, Fitzwilliam Place, Dublin, Ireland View this office online at: https://www.newofficeeurope.com/details/serviced-offices-fitzwilliam-hall-plac e-dublin This business centre is situated in a prestigious area of the city, within an imposing Georgian building. The interior has been refurbished to the highest standards, providing a stylish and modern working environment in which your business can flourish. The services and facilities provided here have led to the business centre being recognised as a five-star business facility. The property has its own restaurant and lounge, kitchen and shower facilities, the highest quality IT systems as well as staff to assist with admin and IT issues. The centre is available 24 hours a day and has security in place. In addition, there is tenant car parking available. Lease options can be tailor made to suit your individual requirements. Transport links Nearest tube: Luas/Bus/Train/Taxi 2 minutes Nearest railway station: 5 minutes' walk Nearest road: Luas/Bus/Train/Taxi 2 minutes Nearest airport: Luas/Bus/Train/Taxi 2 minutes Key features 24 hour access Access to multiple centres nation-wide Administrative support AV equipment Car parking spaces Close to railway station Comfortable lounge Conference rooms Conference rooms Furnished workspaces High-speed internet High-speed internet (dedicated) Hot desking IT support available Kitchen facilities Meeting rooms Modern interiors Near to subway / underground station Open plan workstations Period building Reception staff Restaurant in the building Security system Shower cubicles Telephone answering service Town centre location Unbranded offices Video conference facilities Wireless networking Location This property is in a great city centre location. -

A History of the County Dublin; the People, Parishes and Antiquities from the Earliest Times to the Close of the Eighteenth Cent

A^ THE LIBRARY k OF ^ THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES ^ ^- "Cw, . ^ i^^^ft^-i' •-. > / • COUNTY ,r~7'H- O F XILDA Ji£ CO 17 N T r F W I C K L O \^ 1 c A HISTORY OF THE COUNTY DUBLIN THE PEOPLE, PARISHES AND ANTIQUITIES FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO THE CLOSE OF THE FIGIITKFXTH CENTURY. PART THIRD Beinsj- a History of that portion of the County comprised within the Parishes of TALLAGHT, CRUAGH, WHITEGHURCH, KILGOBBIN, KILTIERNAN, RATHMIGHAEL, OLD GONNAUGHT, SAGGART, RATHCOOLE. AND NEWGASTLE. BY FRANXIS ELRINGTON BALL. DUBLIN: Printed and Published hv Alex. Thom & Co. (Limited), Abbuv-st. 1905. :0 /> 3 PREFACE TO THE THIRD PART. To the readers who ha\c sliowii so ;^fiitifyiii^' an interest in flio progress of my history there is (hie an apolo^^y Tor the tinu; whieli has e]a|)se(l since, in the preface to the seroml pai't, a ho[)e was ex[)rcsse(l that a further Jiistalnient wouhl scjoii ap])eai-. l^lie postpononient of its pvil)lication has l)een caused hy the exceptional dil'licuhy of ohtaiiiin;^' inl'orniat ion of liis- torical interest as to tlie district of which it was j^roposed to treat, and even now it is not witliout hesitation that tliis [)art has heen sent to jiress. Its pages will he found to deal with a poidion of the metro- politan county in whitdi the population has heen at no time great, and in whi(di resid( ncc^s of ini])ortanc(> have always heen few\ Su(di annals of the district as exist relate in most cases to some of the saddest passages in Irish history, and tell of fire and sw^ord and of destruction and desolation.