On Assignment: a Guide to Reporting in Dangerous Situations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

15-L-1645/0 0 0 /194

(b )( 1) (b)(3) NatSecAct TS::SC'l' Verbatim Transcript of Combatant Status Review Tribunal Hearing for IS'.'1 10024 OPENING REPORTER : On the record RECORDER: All rise. PRESIDENT: Remain seated and come to order. Go nhead. Recorder. RECORDER: This Tribunal is being conducle<l at 1328 March 10, 200 ; on board C.S. Naval Base Guantanamo Bav. Cuba. The following personnel are present: Captain (b)(6) United Slates Navy, President Lieutenant Colonel b) 6) • t..:nited States Air Force. Member Lieutenant Colonel (b)(6) United States Marine Corps. Member Lieutenant Colonel (b)(6) , United States Air F11rce, Personal Re pre sen ta the Language Analysis.+.--,...,..,,.,.---. (b)(6) ......... ..,.... Gunnery Sergeant (b)(6) l nited States Marine Corps. Reporter Lieutenant Colonel'-P!!~~) --"" . United States Anny, Recorder Captain (b)(6) 1:; c ge Advocate member »fthe Tribunal. OATH SESSION 1 RECORDER: All Rise. PRESIDE!\T: The Recorder will be sworn. Do you, Lieutenant Colonel j(b)(6) I solemnly swear that you will faithfully pcrfonn the duties as Recorder assigned in this Tribunai so help you God'' RECORDER: I do. PRESIDENT: The Reponer will now be :;worn. The Recorder will administer the oath. RECORDER: ()o you Gunnery Sergeant l(b)(6) ~wear or affinn that y<•u will faithfully <lis~: harge )'Our duties as Reporter assigned in this Tribunal ro help you God? REPORTER: I do. PRESIDENT: The Translator will be sworn. JSN #10024 Enclosure (3) Page I of27 (b )( 1) (b)(3) NatSecAct 15-L-1645/0 0 0/194 (b }( 1) (b)(3) NatSecAct TS:lSCJt RECORDER: Do you swear or affinn that you will faithrully perform 1he duties ofTranslaror in the case now in hearing so help you God? TRANSLATOR: I do PRESIDEN I': We will take a brief recess now in order in lo bring Detainee into the room. -

Global Philanthropy Forum Conference April 18–20 · Washington, Dc

GLOBAL PHILANTHROPY FORUM CONFERENCE APRIL 18–20 · WASHINGTON, DC 2017 Global Philanthropy Forum Conference This book includes transcripts from the plenary sessions and keynote conversations of the 2017 Global Philanthropy Forum Conference. The statements made and views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of GPF, its participants, World Affairs or any of its funders. Prior to publication, the authors were given the opportunity to review their remarks. Some have made minor adjustments. In general, we have sought to preserve the tone of these panels to give the reader a sense of the Conference. The Conference would not have been possible without the support of our partners and members listed below, as well as the dedication of the wonderful team at World Affairs. Special thanks go to the GPF team—Suzy Antounian, Bayanne Alrawi, Laura Beatty, Noelle Germone, Deidre Graham, Elizabeth Haffa, Mary Hanley, Olivia Heffernan, Tori Hirsch, Meghan Kennedy, DJ Latham, Jarrod Sport, Geena St. Andrew, Marla Stein, Carla Thorson and Anna Wirth—for their work and dedication to the GPF, its community and its mission. STRATEGIC PARTNERS Newman’s Own Foundation USAID The David & Lucile Packard The MasterCard Foundation Foundation Anonymous Skoll Foundation The Rockefeller Foundation Skoll Global Threats Fund Margaret A. Cargill Foundation The Walton Family Foundation Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation The World Bank IFC (International Finance SUPPORTING MEMBERS Corporation) The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust MEMBERS Conrad N. Hilton Foundation Anonymous Humanity United Felipe Medina IDB Omidyar Network Maja Kristin Sall Family Foundation MacArthur Foundation Qatar Foundation International Charles Stewart Mott Foundation The Global Philanthropy Forum is a project of World Affairs. -

Adjudicating Human Rights in Transitional Contexts: a Nigerian Case-Study, 1999-2009 Basil Emeka Ugochukwu

Osgoode Hall Law School of York University Osgoode Digital Commons PhD Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2014 Adjudicating Human Rights in Transitional Contexts: A Nigerian Case-Study, 1999-2009 Basil Emeka Ugochukwu Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/phd Part of the Human Rights Law Commons Recommended Citation Ugochukwu, Basil Emeka, "Adjudicating Human Rights in Transitional Contexts: A Nigerian Case-Study, 1999-2009 " (2014). PhD Dissertations. 1. http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/phd/1 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in PhD Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Osgoode Digital Commons. Adjudicating Human Rights in Transitional Contexts: A Nigerian Case-Study, 1999-2009 Basil Emeka Ugochukwu A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Law, Osgoode Hall Law School York University, Toronto, Ontario March 2014 © Basil Emeka Ugochukwu, 2014 Abstract While transitional justice and democracy literature bristles with the expectation that human rights conditions would improve with the progression from the “darkness” of a dictatorship to the “light” of democratic rule, Nigeria’s transition to civil rule in 1999 would seem to provide a sobering contra-reality. Democracy does not seem to have produced a better human rights environment in the post-transition Nigerian context. This dissertation answers the question why the restoration of civil rule in Nigeria has not translated to results in human rights practices that come close to matching the expectations of its citizens and the predictions of transitional justice literature? It investigates, however, only the extent to which human rights violations correlates with the lack of effective judicial protection of those rights between 1999 and 2009. -

2018-12-14 Thesis Final Version

MEMORY, SPACE & LAW MEMORY SITES OF THE 1992-1995 WAR IN PRESENT DAY BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA AND THE INTEGRATION OF THE ICTY LEGACY. Scientific article Word count: 9.485 Aurore Vanliefde Student number: 01708804 Promotor: Dr. David Mwambari Master’s thesis presented for obtaining the degree of Master in Conflict and Development Academic year: 2018-2019 MEMORY, SPACE & LAW. MEMORY SITES OF THE 1992-1995 WAR IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA AND THE INTEGRATION OF THE ICTY LEGACY. Abstract This article revolves around memorialisation of the 1992-1995 war in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH). Theoretical insights from literature are combined with empirical data from 29 memory sites in BiH, two expert interviews, and additional information from informal conversations with guides and participation in guided tours. The aim of this study is to understand the use of memory sites of the 1992-1995 war in BiH, and research the extent to which the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY)’s legacy has been integrated into these memory sites. The findings show that memorialisation is on-going through the creation, conservation, accentuation and destruction of memory sites. Memorials are generally exclusively meant for one ethno-national group, and are often the product of local and/or private initiatives. These sites of memory are lieux de mémoire, as described by Pierre Nora, where a community’s collective memory is both materialised and generated. Personal testimonies are extensively used in museums and archival material from the ICTY is included in some memory sites. The ICTY’s legacy constitutes a unique kind of memory, a lieu de mémoire sui generis. -

Video-Recorded Decapitations - a Seemingly Perfect Terrorist Tactic That Did Not Spread Martin Harrow DIIS Working Paper 2011:08 WORKING PAPER

DIIS working paper DIIS WORKING PAPER 2011:08 Video-recorded Decapitations - A seemingly perfect terrorist tactic that did not spread Martin Harrow DIIS Working Paper 2011:08 WORKING PAPER 1 DIIS WORKING PAPER 2011:08 MARTIN HARROW MSC, PhD, Consulting Analyst at DIIS [email protected] DIIS Working Papers make available DIIS researchers’ and DIIS project partners’ work in progress towards proper publishing. They may include important documentation which is not necessarily published elsewhere. DIIS Working Papers are published under the responsibility of the author alone. DIIS Working Papers should not be quoted without the express permission of the author. DIIS WORKING PAPER 2011:08 © Copenhagen 2011 Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover Design: Carsten Schiøler Layout: Ellen-Marie Bentsen Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN: 978-87-7605-449-6 Price: DKK 25.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk 2 DIIS WORKING PAPER 2011:08 CONTENTS Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Decapitation as a weapon 5 Video-recorded decapitations 2002-2009 8 The reproductive dynamics of terrorist tactics 11 The accessibility of video-recorded decapitations as a tactic 12 Effectiveness of terrorism – impacting two different audiences 14 Why not video-recorded decapitations? 18 Iraq 18 Afghanistan 19 The West 20 Conclusion 21 List of References 23 DIIS WORKING PAPER 2011:08 ABSTracT Video-recorded decapitations have an enormous impact, they are cheap and easy, and they allow the terrorists to exploit the potential of the Internet. -

Pakistan's Terrorism Dilemma

14 HUSAIN HAQQANI Pakistan’s Terrorism Dilemma For more than a decade, Pakistan has been accused of sup- porting terrorism, primarily due to its support for militants opposing Indian rule in the disputed Himalayan territory of Jammu and Kashmir. Until September 11, 2001, Islamabad was also the principal backer of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. Although Pakistan has now become a key U.S. ally in the war against terrorism, it is still seen both as a target and staging ground for terrorism. General Pervez Musharraf ’s military regime abandoned its alliance with the Taliban immediately after the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington. U.S. forces were allowed the use of Pakistani air bases for operations in Afghanistan. Pakistani intelligence services provided, and continue to provide, valuable information in hunting down Taliban and al-Qaeda escapees. The Pakistani military is cur- rently working with U.S. law enforcement officials in tracking down terrorists in the lawless tribal areas bordering Afghanistan. In a major policy speech on January 12, 2002, Musharraf announced measures to limit the influence of Islamic militants at home, including those previously described by him as “Kashmiri free- dom fighters.” “No organizations will be able to carry out terrorism 351 352 HUSAIN HAQQANI on the pretext of Kashmir,” he declared. “Whoever is involved with such acts in the future will be dealt with strongly whether they come from inside or outside the country.”1 Musharraf ’s supporters declared his speech as revolutionary.2 He echoed the sentiment of most Pakistanis when he said, “violence and terrorism have been going on for years and we are weary and sick of this Kalashnikov culture … The day of reckoning has come.” After the speech, the Musharraf regime clamped down on domes- tic terrorist groups responsible for sectarian killings.3 But there is still considerable ambivalence in Pakistan’s attitude toward the Kashmiri militants. -

Torture and the Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment of Detainees: the Effectiveness and Consequences of 'Enhanced

TORTURE AND THE CRUEL, INHUMAN AND DE- GRADING TREATMENT OF DETAINEES: THE EFFECTIVENESS AND CONSEQUENCES OF ‘EN- HANCED’ INTERROGATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE CONSTITUTION, CIVIL RIGHTS, AND CIVIL LIBERTIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 8, 2007 Serial No. 110–94 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://judiciary.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 38–765 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:46 Jul 29, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\WORK\CONST\110807\38765.000 HJUD1 PsN: 38765 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan, Chairman HOWARD L. BERMAN, California LAMAR SMITH, Texas RICK BOUCHER, Virginia F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., JERROLD NADLER, New York Wisconsin ROBERT C. ‘‘BOBBY’’ SCOTT, Virginia HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina ELTON GALLEGLY, California ZOE LOFGREN, California BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas STEVE CHABOT, Ohio MAXINE WATERS, California DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts CHRIS CANNON, Utah ROBERT WEXLER, Florida RIC KELLER, Florida LINDA T. SA´ NCHEZ, California DARRELL ISSA, California STEVE COHEN, Tennessee MIKE PENCE, Indiana HANK JOHNSON, Georgia J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia BETTY SUTTON, Ohio STEVE KING, Iowa LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois TOM FEENEY, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California TRENT FRANKS, Arizona TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin LOUIE GOHMERT, Texas ANTHONY D. -

Leaderless Jihad West Point Ctc Summaries

ALL FEl INFflRNITIuII CONTAINED NEPEIN Tl1JCLPSIFIED DATE O1 LI 5l DIm1shn WEST POINT CTC SUMMARIES IC LEADERLESS JIHAD Terror Networks in the Twenty-First Century flivcrsit\ Pclms\ 1\ jnia Press 2015 The Islamist terrorist threat is radicalization Dr Marc Sageman MD global rapidly evolving process Islamic terror networks of the twenty-first century are before it reaches its Ph.D is forensic psychia more fluid and violent end The most effective trist and government coun becoming independent unpredictable than their more structured forebears that conducted countermeasure to tcrtcrrorism consultant He This book builds combat the homegrown holds various academic and die 9/11 attacks The present direat in the West has upon Dr Sagemans terrorist threat is evolved from infiltration outside trained includ by terronsts to the professional positions previous volume interrupt Scholar in Residence against ivhom international cooperation and border radicalization process ing at Understanding Ter before effective it reaches its the York Police protection are to homegrown self-financed New Depart ror 1\Tetlrorks 2004 vioient end Senior Fellow the self-trained terrorists Dr Sageman describes this ment at and utilizes die same scattered network of wannabes Research In global homegrown Porcign Policy approach of apply- as leaderless ihad The that form this stitute and Clinical Assistant groups ing the scientific method to the study of terronsm movement are physically uncoimected from al Qaeda Professor at the University Whereas in his book the author worked -

Global War on Terrorism and Prosecution of Terror Suspects: Select Cases and Implications for International Law, Politics, and Security

GLOBAL WAR ON TERRORISM AND PROSECUTION OF TERROR SUSPECTS: SELECT CASES AND IMPLICATIONS FOR INTERNATIONAL LAW, POLITICS, AND SECURITY Srini Sitaraman Introduction The global war on terrorism has opened up new frontiers of transnational legal challenge for international criminal law and counterterrorism strategies. How do we convict terrorists who transcend multiple national boundaries for committing and plotting mass atrocities; what are the hurdles in extraditing terrorism suspects; what are the consequences of holding detainees in black sites or secret prisons; what interrogation techniques are legal and appropriate when questioning terror suspects? This article seeks to examine some of these questions by focusing on the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT), particularly in the context of counterterrorism strategies that the United States have pursued towards Afghanistan-Pakistan (Af-Pak) since the September 2001 terror attacks on New York and Washington D.C. The focus of this article is on the methods employed to confront terror suspects and terror facilitators and not on the politics of cooperation between the United States and Pakistan on the Global War on Terrorism or on the larger military operation being conducted in Afghanistan and in the border regions of Pakistan. This article is not positioned to offer definitive answers or comprehensive analyses of all pertinent issues associated with counterterrorism strategies and its effectiveness, which would be beyond the scope of this effort. The objective is to raise questions about the policies that the United States have adopted in conducting the war on terrorism and study its implications for international law and security. It is to examine whether the overzealousness in the execution of this war on terror has generated some unintended consequences for international law and complicated the global judicial architecture in ways that are not conducive to the democratic propagation of human rights. -

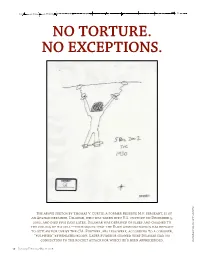

No Torture. No Exceptions

NO TORTURE. NO EXCEPTIONS. The above sketch by Thomas V. Curtis, a former Reserve M.P. sergeant, is of New York Times an Afghan detainee, Dilawar, who was taken into U.S. custody on December 5, 2002, and died five days later. Dilawar was deprived of sleep and chained to the ceiling of his cell—techniques that the Bush administration has refused to outlaw for use by the CIA. Further, his legs were, according to a coroner, “pulpified” by repeated blows. Later evidence showed that Dilawar had no connection to the rocket attack for which he’d been apprehended. A sketch by Thomas Curtis, V. a Reserve M.P./The 16 January/February/March 2008 Introduction n most issues of the Washington Monthly, we favor ar- long-term psychological effects also haunt patients—panic ticles that we hope will launch a debate. In this issue attacks, depression, and symptoms of post-traumatic-stress Iwe seek to end one. The unifying message of the ar- disorder. It has long been prosecuted as a crime of war. In our ticles that follow is, simply, Stop. In the wake of Septem- view, it still should be. ber 11, the United States became a nation that practiced Ideally, the election in November would put an end to torture. Astonishingly—despite the repudiation of tor- this debate, but we fear it won’t. John McCain, who for so ture by experts and the revelations of Guantanamo and long was one of the leading Republican opponents of the Abu Ghraib—we remain one. As we go to press, President White House’s policy on torture, voted in February against George W. -

Antiretroviral Price Reductions

UNTANGLING THE WEB OF ANTIRETROVIRAL PRICE REDUCTIONS 18th Edition – July 2016 www.msfaccess.org PREFACE In this report, we provide an update on the key facets of HIV treatment access. It includes the latest HIV treatment guidelines from World Health Organization (WHO), an overview on pricing for first-line, second-line and salvage regimens, and a summary of the opportunities for – and threats to – expanding access to affordable antiretroviral therapy (ART). There is a table with information on ARVs, including quality assurance, manufacturers and pricing on pages 55 to 57. THE MSF ACCESS CAMPAIGN In 1999, on the heels of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize – and largely in response to the inequalities surrounding access to HIV/AIDS treatment between rich and poor countries – MSF launched the Campaign for Access to Essential Medicines. Its sole purpose has been to push for access to, and the development of, life-saving and life-prolonging medicines, diagnostics and vaccines for patients in MSF programmes and beyond. www.msfaccess.org MSF AND HIV Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) began providing antiretroviral therapy to a small number of people living with HIV/AIDS in 2000 in projects in Thailand, South Africa and Cameroon. At the time, treatment for one person for one year cost more than US$10,000. With increased availability of low-cost, quality antiretroviral drugs (ARVs), MSF provides antiretroviral treatment to 240,100 people in 18 countries, implements treatment strategies to reach more people earlier in their disease progression, and places people living with HIV at the centre of their care. -

New South African Constitution and Ethnic Division, the Stephen Ellmann New York Law School, [email protected]

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters 1994 New South African Constitution and Ethnic Division, The Stephen Ellmann New York Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Recommended Citation 26 Colum. Hum. Rts. L. Rev. 5 (1994-1995) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. THE NEW SOUTH AFRICAN CONSTITUTION AND ETHNIC DIVISION by Stephen Ellmann* I. INTRODUCTION In an era of ethnic slaughter in countries from Bosnia to Rwanda, the peril of ethnic division cannot be ignored. Reducing that peril by constitutional means is no simple task, for when ethnic groups pull in different directions a free country can only produce harmony between them by persuading each to honor some claims of the other and to moderate some claims of its own. It will require much more than technical ingenuity in constitution-writing to generate such mutual forbearance. Moreover, constitutional provisions that promote this goal will inevitably do so at a price - namely, the reduction of any single group's ability to work its will through the political process. And that price is likely to be most painful to pay when it entails restraining a group's ability to achieve goals that are just - for example, when it limits the ability of the victims of South African apartheid to redress the profound injustice they have suffered. This Article examines the efforts of the drafters of the new transitional South African Constitution to overcome ethnic division, or alternatively to accommodate it.