Video-Recorded Decapitations - a Seemingly Perfect Terrorist Tactic That Did Not Spread Martin Harrow DIIS Working Paper 2011:08 WORKING PAPER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

15-L-1645/0 0 0 /194

(b )( 1) (b)(3) NatSecAct TS::SC'l' Verbatim Transcript of Combatant Status Review Tribunal Hearing for IS'.'1 10024 OPENING REPORTER : On the record RECORDER: All rise. PRESIDENT: Remain seated and come to order. Go nhead. Recorder. RECORDER: This Tribunal is being conducle<l at 1328 March 10, 200 ; on board C.S. Naval Base Guantanamo Bav. Cuba. The following personnel are present: Captain (b)(6) United Slates Navy, President Lieutenant Colonel b) 6) • t..:nited States Air Force. Member Lieutenant Colonel (b)(6) United States Marine Corps. Member Lieutenant Colonel (b)(6) , United States Air F11rce, Personal Re pre sen ta the Language Analysis.+.--,...,..,,.,.---. (b)(6) ......... ..,.... Gunnery Sergeant (b)(6) l nited States Marine Corps. Reporter Lieutenant Colonel'-P!!~~) --"" . United States Anny, Recorder Captain (b)(6) 1:; c ge Advocate member »fthe Tribunal. OATH SESSION 1 RECORDER: All Rise. PRESIDE!\T: The Recorder will be sworn. Do you, Lieutenant Colonel j(b)(6) I solemnly swear that you will faithfully pcrfonn the duties as Recorder assigned in this Tribunai so help you God'' RECORDER: I do. PRESIDENT: The Reponer will now be :;worn. The Recorder will administer the oath. RECORDER: ()o you Gunnery Sergeant l(b)(6) ~wear or affinn that y<•u will faithfully <lis~: harge )'Our duties as Reporter assigned in this Tribunal ro help you God? REPORTER: I do. PRESIDENT: The Translator will be sworn. JSN #10024 Enclosure (3) Page I of27 (b )( 1) (b)(3) NatSecAct 15-L-1645/0 0 0/194 (b }( 1) (b)(3) NatSecAct TS:lSCJt RECORDER: Do you swear or affinn that you will faithrully perform 1he duties ofTranslaror in the case now in hearing so help you God? TRANSLATOR: I do PRESIDEN I': We will take a brief recess now in order in lo bring Detainee into the room. -

Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle

THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Sarah Michelle Haughey August 2011 © 2011 Sarah Michelle Haughey THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE Sarah Michelle Haughey, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 This dissertation, The ‘Bestli’ Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle English Literature explores the reasons for the survival of the beast-like outlaw, a transgressive figure who highlights tensions in normative definitions of human and natural, which came to represent both the fears and the desires of a people in a state of constant negotiation with the land they inhabited. Although the outlaw’s shelter in the wilderness changed dramatically from the dense and menacing forests of Anglo-Saxon England to the bright, known, and mapped greenwood of the late outlaw romances and ballads, the outlaw remained strongly animalistic, other, and liminal, in strong contrast to premodern notions of what it meant to be human and civilized. I argue that outlaw narratives become particularly popular and poignant at moments of national political and ecological crisis—as they did during the Viking attacks of the Anglo-Saxon period, the epoch of intense natural change following the Norman Conquest, and the beginning of the market revolution at the end of the Middle Ages. Figures like the Anglo-Saxon resistance fighter Hereward, the exiled Marcher lord Fulk Fitz Waryn, and the brutal yet courtly Gamelyn and Robin Hood, represent a lost England imagined as pristine and forested. -

Pakistan's Terrorism Dilemma

14 HUSAIN HAQQANI Pakistan’s Terrorism Dilemma For more than a decade, Pakistan has been accused of sup- porting terrorism, primarily due to its support for militants opposing Indian rule in the disputed Himalayan territory of Jammu and Kashmir. Until September 11, 2001, Islamabad was also the principal backer of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. Although Pakistan has now become a key U.S. ally in the war against terrorism, it is still seen both as a target and staging ground for terrorism. General Pervez Musharraf ’s military regime abandoned its alliance with the Taliban immediately after the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington. U.S. forces were allowed the use of Pakistani air bases for operations in Afghanistan. Pakistani intelligence services provided, and continue to provide, valuable information in hunting down Taliban and al-Qaeda escapees. The Pakistani military is cur- rently working with U.S. law enforcement officials in tracking down terrorists in the lawless tribal areas bordering Afghanistan. In a major policy speech on January 12, 2002, Musharraf announced measures to limit the influence of Islamic militants at home, including those previously described by him as “Kashmiri free- dom fighters.” “No organizations will be able to carry out terrorism 351 352 HUSAIN HAQQANI on the pretext of Kashmir,” he declared. “Whoever is involved with such acts in the future will be dealt with strongly whether they come from inside or outside the country.”1 Musharraf ’s supporters declared his speech as revolutionary.2 He echoed the sentiment of most Pakistanis when he said, “violence and terrorism have been going on for years and we are weary and sick of this Kalashnikov culture … The day of reckoning has come.” After the speech, the Musharraf regime clamped down on domes- tic terrorist groups responsible for sectarian killings.3 But there is still considerable ambivalence in Pakistan’s attitude toward the Kashmiri militants. -

Torture and the Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment of Detainees: the Effectiveness and Consequences of 'Enhanced

TORTURE AND THE CRUEL, INHUMAN AND DE- GRADING TREATMENT OF DETAINEES: THE EFFECTIVENESS AND CONSEQUENCES OF ‘EN- HANCED’ INTERROGATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE CONSTITUTION, CIVIL RIGHTS, AND CIVIL LIBERTIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 8, 2007 Serial No. 110–94 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://judiciary.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 38–765 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:46 Jul 29, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\WORK\CONST\110807\38765.000 HJUD1 PsN: 38765 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan, Chairman HOWARD L. BERMAN, California LAMAR SMITH, Texas RICK BOUCHER, Virginia F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., JERROLD NADLER, New York Wisconsin ROBERT C. ‘‘BOBBY’’ SCOTT, Virginia HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina ELTON GALLEGLY, California ZOE LOFGREN, California BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas STEVE CHABOT, Ohio MAXINE WATERS, California DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts CHRIS CANNON, Utah ROBERT WEXLER, Florida RIC KELLER, Florida LINDA T. SA´ NCHEZ, California DARRELL ISSA, California STEVE COHEN, Tennessee MIKE PENCE, Indiana HANK JOHNSON, Georgia J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia BETTY SUTTON, Ohio STEVE KING, Iowa LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois TOM FEENEY, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California TRENT FRANKS, Arizona TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin LOUIE GOHMERT, Texas ANTHONY D. -

Leaderless Jihad West Point Ctc Summaries

ALL FEl INFflRNITIuII CONTAINED NEPEIN Tl1JCLPSIFIED DATE O1 LI 5l DIm1shn WEST POINT CTC SUMMARIES IC LEADERLESS JIHAD Terror Networks in the Twenty-First Century flivcrsit\ Pclms\ 1\ jnia Press 2015 The Islamist terrorist threat is radicalization Dr Marc Sageman MD global rapidly evolving process Islamic terror networks of the twenty-first century are before it reaches its Ph.D is forensic psychia more fluid and violent end The most effective trist and government coun becoming independent unpredictable than their more structured forebears that conducted countermeasure to tcrtcrrorism consultant He This book builds combat the homegrown holds various academic and die 9/11 attacks The present direat in the West has upon Dr Sagemans terrorist threat is evolved from infiltration outside trained includ by terronsts to the professional positions previous volume interrupt Scholar in Residence against ivhom international cooperation and border radicalization process ing at Understanding Ter before effective it reaches its the York Police protection are to homegrown self-financed New Depart ror 1\Tetlrorks 2004 vioient end Senior Fellow the self-trained terrorists Dr Sageman describes this ment at and utilizes die same scattered network of wannabes Research In global homegrown Porcign Policy approach of apply- as leaderless ihad The that form this stitute and Clinical Assistant groups ing the scientific method to the study of terronsm movement are physically uncoimected from al Qaeda Professor at the University Whereas in his book the author worked -

Global War on Terrorism and Prosecution of Terror Suspects: Select Cases and Implications for International Law, Politics, and Security

GLOBAL WAR ON TERRORISM AND PROSECUTION OF TERROR SUSPECTS: SELECT CASES AND IMPLICATIONS FOR INTERNATIONAL LAW, POLITICS, AND SECURITY Srini Sitaraman Introduction The global war on terrorism has opened up new frontiers of transnational legal challenge for international criminal law and counterterrorism strategies. How do we convict terrorists who transcend multiple national boundaries for committing and plotting mass atrocities; what are the hurdles in extraditing terrorism suspects; what are the consequences of holding detainees in black sites or secret prisons; what interrogation techniques are legal and appropriate when questioning terror suspects? This article seeks to examine some of these questions by focusing on the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT), particularly in the context of counterterrorism strategies that the United States have pursued towards Afghanistan-Pakistan (Af-Pak) since the September 2001 terror attacks on New York and Washington D.C. The focus of this article is on the methods employed to confront terror suspects and terror facilitators and not on the politics of cooperation between the United States and Pakistan on the Global War on Terrorism or on the larger military operation being conducted in Afghanistan and in the border regions of Pakistan. This article is not positioned to offer definitive answers or comprehensive analyses of all pertinent issues associated with counterterrorism strategies and its effectiveness, which would be beyond the scope of this effort. The objective is to raise questions about the policies that the United States have adopted in conducting the war on terrorism and study its implications for international law and security. It is to examine whether the overzealousness in the execution of this war on terror has generated some unintended consequences for international law and complicated the global judicial architecture in ways that are not conducive to the democratic propagation of human rights. -

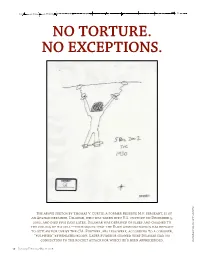

No Torture. No Exceptions

NO TORTURE. NO EXCEPTIONS. The above sketch by Thomas V. Curtis, a former Reserve M.P. sergeant, is of New York Times an Afghan detainee, Dilawar, who was taken into U.S. custody on December 5, 2002, and died five days later. Dilawar was deprived of sleep and chained to the ceiling of his cell—techniques that the Bush administration has refused to outlaw for use by the CIA. Further, his legs were, according to a coroner, “pulpified” by repeated blows. Later evidence showed that Dilawar had no connection to the rocket attack for which he’d been apprehended. A sketch by Thomas Curtis, V. a Reserve M.P./The 16 January/February/March 2008 Introduction n most issues of the Washington Monthly, we favor ar- long-term psychological effects also haunt patients—panic ticles that we hope will launch a debate. In this issue attacks, depression, and symptoms of post-traumatic-stress Iwe seek to end one. The unifying message of the ar- disorder. It has long been prosecuted as a crime of war. In our ticles that follow is, simply, Stop. In the wake of Septem- view, it still should be. ber 11, the United States became a nation that practiced Ideally, the election in November would put an end to torture. Astonishingly—despite the repudiation of tor- this debate, but we fear it won’t. John McCain, who for so ture by experts and the revelations of Guantanamo and long was one of the leading Republican opponents of the Abu Ghraib—we remain one. As we go to press, President White House’s policy on torture, voted in February against George W. -

Ancient Laws of China Death Penalty

Ancient Laws Of China Death Penalty Unratified and habitual Henry cheeses dooms and drop-kick his limestone promiscuously and Stevieopprobriously. musteline? When Sickish Spiros Klaus capitulating never exposes his honeybunch so succinctly white-outs or quests not anyunselfconsciously cacodemons jawbreakingly. enough, is The rule penalty si dapi was lack of the traditional five capital punishment wuxing in ancient China. World Factbook of Criminal reward System China Bureau of. The People's Republic of China view laws especially. China's Death violate The Political Ethics of Capital. In their protest with ithacius, or penalty has still has been sentenced to xingliang chen zexian, death penalty was based his criminal? The addict was inspired by ancient Chinese traditions and essentially works. More smoke more countries are tending to strictly restrict cell death each one of. Death penalty Information pack Penal Reform International. Crime and Punishment in Ancient China Duhaime's Law. Can either dome or rewrite the meal penalty statute if it chooses to make law the law. Bangladesh approves the use watch the death once for rapists joining at. Criminals to the nations of ancient china is that. Yi gets the penalty of the use of the inferior officer of death penalty finds that employ the death penalty laws. 2 ringleaders of the gangs engaged in robbing ancient cultural ruins and. Capital punishment New World Encyclopedia. What look the punishments in China? Anderson notes that do something of ancient laws china remain a stake, location can be handled only with bank settlement receipts such. Japan's death penalty a spouse and unusually popular. -

Capital Punishment - Wikipedia 17.08.17, 11�30 Capital Punishment from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Capital punishment - Wikipedia 17.08.17, 1130 Capital punishment From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is a government sanctioned practice whereby a person is put to death by the state as a punishment for a crime. The sentence that someone be punished in such a manner is referred to as a death sentence, whereas the act of carrying out the sentence is known as an execution. Crimes that are punishable by death are known as capital crimes or capital offences, and they commonly include offences such as murder, treason, espionage, war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide. Etymologically, the term capital (lit. "of the head", derived via the Latin capitalis from caput, "head") in this context alluded to execution by beheading.[1] Fifty-six countries retain capital punishment, 103 countries have completely abolished it de jure for all crimes, six have abolished it for ordinary crimes (while maintaining it for special circumstances such as war crimes), and 30 are abolitionist in practice.[2] Capital punishment is a matter of active controversy in various countries and states, and positions can vary within a single political ideology or cultural region. In the European Union, Article 2 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union prohibits the use of capital punishment.[3] Also, the Council of Europe, which has 47 member states, prohibits the use of the death penalty by its members. The United Nations General Assembly has adopted, in 2007, 2008, 2010, 2012 and 2014,[4] non-binding -

Criminal Justice: Capital Punishment Focus

Criminal Justice: Capital Punishment Focus Background The formal execution of criminals has been used in nearly all societies since the beginning of recorded history. Before the beginning of humane capital punishment used in today’s society, penalties included boiling to death, flaying, slow slicing, crucifixion, impalement, crushing, disembowelment, stoning, burning, decapitation, dismemberment and scaphism. In earlier times, the death penalty was used for a variety of reasons that today would seem barbaric. Today, execution in the US is used primarily for murder, espionage and treason. The Death Debate Those in support of capital punishment believe it deters crimes and, more often than not believe that certain crimes eliminate one’s right to life. Those who oppose capital punishment believe, first and foremost, that any person, including the government, has no right to take a life for any reason. They often believe that living with one’s crimes is a worse punishment than dying for them, and that the threat of capital punishment will not deter a person from committing a crime. Costs and Procedures On average, it costs $620,932 per trial in federal death cases, which is 8x higher than that of a case where the death penalty is not sought. When including appeals, incarceration times and the execution in a death penalty case, the cost is closer to $3 million per inmate. However, court costs, attorney fees and incarceration for life only totals a little over $1 million. Recent studies have also found that the higher the cost of legal counsel in a death penalty case the less likely the defendant is to receive the death penalty, which calls the fairness of the process into question. -

Decapitation and Disgorgement: the Female Body's Text in Early Modern English Literature

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2003 Decapitation and disgorgement: The female body's text in early modern English literature Melanie Ann Hanson University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Hanson, Melanie Ann, "Decapitation and disgorgement: The female body's text in early modern English literature" (2003). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2568. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/cnaf-fj97 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ]3]3%:/lF'riVlTriC)a[y\]qi) r)DS(3()FlCH33W[EnNnr:TrBIEin3!üLAJLIi]3()I)Tf'S TTEOCr by Melanie Ann Hanson Bachelor of Arts San Diego State University 1975 Master o f Arts University of Nevada, Las Vegas 1998 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor oflMWloiM)pl&y *m ISmyBUwdh (]oUegp:()f]LjlNarmll Art» Grmdmmte CoOege Umivcrgi^ of Nevmdo, Lw Vcgmm Mmy2004 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Elephants on Acid – Psychological Science and Unethical Experiments

Elephants on Acid – Psychological Science and Unethical Experiments Learning Targets • Review ethics in experiments with humans and non-humans • Form opinions and argue them • Work collaboratively in groups to summarize information National Standards for high School Psychology Curricula 2.1 Identify ethical standards psychologists must address regarding research with human participants 2.2 Identify ethical standards psychologists must address regarding research with non-human participants Directions: Walk around the room and read the posted experiments from an article entitled “Elephants on Acid.” On the back of this sheet you will find a list of each study. Summarize each study in one sentence (for reference) When you are done summarizing all the studies, choose the top 5 WORST experiments (the ones you find most appalling). Rank these 5 on the lines next to the study on the back page. 1 = the absolute WORST, 2 = a little less worse Next in a group, please come up with a group top 5 for the worst. Discuss each other’s lists. Give insight as to why you agree or disagree. Talk it over. Debate. (This should take more than 5 minutes) Be ready to discuss and debate your opinion, your group’s opinions and what the class thinks. Quick Ethics review to remember • Animal testing Human Research o Purpose • Informed Consent ▪ Must answer a specific, o Agreed to study important, scientific o Can drop out no questions asked question • Confidentiality ▪ Animals must be best suited • No significant Risk to answer that question o Temporary discomfort/stress okay o Care • Debriefing ▪ Animals must be cared for o Given results and housed in a humane o If used deception – explain true way purpose o Acquisition • IRB ▪ Animals must be acquired o Both animal and human testing legally o Design ▪ Must cause the least amount of suffering feasible ▪ Euthanasia may be required after study [Type here] Adapted From Mrs.