Case Scenario Perianesthetic Management of Laryngospasm In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

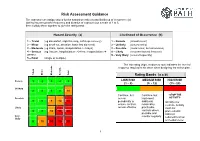

Risk Assessment Guidance

Risk Assessment Guidance The assessor can assign values for the hazard severity (a) and likelihood of occurrence (b) (taking into account the frequency and duration of exposure) on a scale of 1 to 5, then multiply them together to give the rating band: Hazard Severity (a) Likelihood of Occurrence (b) 1 – Trivial (eg discomfort, slight bruising, self-help recovery) 1 – Remote (almost never) 2 – Minor (eg small cut, abrasion, basic first aid need) 2 – Unlikely (occurs rarely) 3 – Moderate (eg strain, sprain, incapacitation > 3 days) 3 – Possible (could occur, but uncommon) 4 – Serious (eg fracture, hospitalisation >24 hrs, incapacitation >4 4 – Likely (recurrent but not frequent) weeks) 5 – Very likely (occurs frequently) 5 – Fatal (single or multiple) The risk rating (high, medium or low) indicates the level of response required to be taken when designing the action plan. Trivial Minor Moderate Serious Fatal Rating Bands (a x b) Remote 1 2 3 4 5 LOW RISK MEDIUM RISK HIGH RISK (1 – 8) (9 - 12) (15 - 25) Unlikely 2 4 6 8 10 Continue, but Continue, but -STOP THE Possible review implement ACTIVITY- 3 6 9 12 15 periodically to additional Identify new ensure controls reasonably controls. Activity Likely remain effective practicable must not controls where 4 8 12 16 20 proceed until possible and risks are Very monitor regularly reduced to a low likely 5 10 15 20 25 or medium level 1 Risk Assessments There are a number of explanations needed in order to understand the process and the form used in this example: HAZARD: Anything that has the potential to cause harm. -

Operational Risk Management Guide

OPERATIONAL RISK MANAGEMENT GUIDE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE 2020 Last Updated 02/26/2020 RISK MANAGEMENT COUNCIL IN COOPERATION WITH THE OFFICE OF SAFETY & OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH and THE NATIONAL AVIATION SAFETY COUNCIL Contents Contents ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................................. i Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................... 1 What is Operational Risk Management? ................................................................................................................... 1 The Terminology of ORM ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Principles of ORM Application ........................................................................................................................................... 6 The Five-Step ORM Process ................................................................................................................................................ 7 Step 1: Identify Hazards .................................................................................................................................................. -

Assigning Risk Assessment Codes

Exhibit 1 240 FW 5 Page 1 of 4 Assigning Risk Assessment Codes The Department of the Interior describes its Risk Assessment System in 485 DM 6, Inspections and Abatements. The policy mandates inspections, assignment of Risk Assessment Codes (RACs) to identified hazards, and abatement of the hazards within certain timeframes. The RACs are based on the hazard severity, probability of occurrence, and number of people exposed or potentially lost in the event of an accident. While all hazards should be resolved as soon as possible, the Risk Assessment System provides managers with safety risk ranking information to assist them in making informed decisions concerning hazard control. It also provides decisionmakers with a consistent and defensible approach to prioritizing safety hazard abatement efforts among the many competing resource demands and priorities. Step 1 – Learn the terminology Hazard – Anything that may cause harm, injury, or ill health. Risk – Risk is a measure of both the likelihood (probability) and the consequence (severity) of all hazards related to an activity or condition. Risk Assessment System (RAS) – A method provided by the Department to assist managers to prioritize safety and health deficiencies. Risk Assessment Code (RAC) – A hazard number ranking system from 1 (the highest level of risk) to 5 (the lowest level of risk). Risk Assessment Matrix – A tool used to assign RACs (see example below). XX/XX/13 OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH Exhibit 1 240 FW 5 Page 2 of 4 Step 2 – Using the RAC Matrix Tool, assigning a code Evaluate each deficiency based on both the likelihood (probability) of an outcome occurring and the consequence (severity) of a potential outcome. -

Incidence of Laryngospasm and Bronchospasm in Pediatric Adenotonsillectomy

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln US Army Research U.S. Department of Defense 2012 Incidence of Laryngospasm and Bronchospasm in Pediatric Adenotonsillectomy Michael I. Orestes Walter Reed Army Medical Center Lina Lander University of Nebraska Medical Center, [email protected] Susan Verghese Children’s National Medical Center Rahul K. Shah Children’s National Medical Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usarmyresearch Orestes, Michael I.; Lander, Lina; Verghese, Susan; and Shah, Rahul K., "Incidence of Laryngospasm and Bronchospasm in Pediatric Adenotonsillectomy" (2012). US Army Research. 257. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usarmyresearch/257 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Defense at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in US Army Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Laryngoscope VC 2012 The American Laryngological, Rhinological and Otological Society, Inc. Incidence of Laryngospasm and Bronchospasm in Pediatric Adenotonsillectomy Michael I. Orestes, MD; Lina Lander, ScD; Susan Verghese, MD; Rahul K. Shah, MD Objectives/Hypothesis: To evaluate and describe airway complications in pediatric adenotonsillectomy. Study Design: Retrospective case-control study. Methods: A chart review of patients that underwent adenotonsillectomy between 2006 and 2010 was performed. Peri- operative complications, patient characteristics, and surgeon and anesthesia technique were recorded. Results: A total of 682 charts were reviewed. Eleven cases (1.6%) of laryngospasm were identified: one was preopera- tive, seven occurred in the operating room postextubation, and three occurred in the recovery area. Four patients were given succinylcholine, one was reintubated, and the other cases were managed conservatively. -

Personal Protective Equipment

LABORATORY BIOSAFETY MANUAL FOURTH EDITION AND ASSOCIATED MONOGRAPHS PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT LABORATORY BIOSAFETY MANUAL FOURTH EDITION AND ASSOCIATED MONOGRAPHS PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT Personal protective equipment (Laboratory biosafety manual, fourth edition and associated monographs) ISBN 978-92-4-001141-0 (electronic version) ISBN 978-92-4-001142-7 (print version) © World Health Organization 2020 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization (http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/ mediation/rules/). Suggested citation. Personal protective equipment. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 (Laboratory biosafety manual, fourth edition and associated monographs). -

Risk Assessment Checklist

Preventing Workplace Harassment & Violence: Toolkit for Trucking & Logistics Employers WORKPLACE HARASSMENT AND VIOLENCE PREVENTION REGULATIONS Workplace Risk Assessment Checklist Recent changes to the Canada Labour Code introduce new obligations for federally regulated employers. One important new piece of legislation is Bill C-65, which protects against harassment and violence in the workplace. BillC-65 introduced new Workplace Harassment and Violence Prevention Regulations, which came into force on January 1st, 2021. Under this new framework, employers are required to conduct a Work Place Risk Assessment as part of their responsibility to prevent workplace harassment and violence. Below you will find a Workplace Risk Assessment Checklist to help monitor your company’s practices and ensure compliance. The checklist contains information that is both required and recommended. Regulatory requirements per the Act are denoted by *. Legal Statement: The information contained within does not constitute legal advice. Trucking HR Canada, and all content contributors bear no responsibility for any circumstances arising out of or related to the adoption, or decision not to adopt any of the recommendations contained in the Workplace Risk Assessment Checklist. WORKPLACE RISK ASSESSMENT CHECKLIST 1 GETTING STARTED *You will be required to complete the workplace assessment with your company’s applicable partner. Depending on the size of your organization, "applicable partner" is defined as the policy committee (for employers with more than 300 employees), the workplace committee (for employers with 20 or more employees), or the health and safety representative (for employers with less than 19 employees). *Ensure individuals that are directed to identify the risks, or to develop and implement the preventative measures, are properly qualified and trained. -

Risk Assessment Checklist

OAKLAND UNIVERSITY RISK ASSSESSMENT CHECKLIST Prior to each event, a systematic approach must be taken to establish proper security for each event. With appropriate steps we can minimize risk.The staff and management will be prepared to prevent, anticipate and handle problems. Listed below is a basic checklist which will be adjusted accordingly for each event. 1. Review Changes - In the preplanning stages, review any changes to be made from the previous year's event. 2. Meet With OUPD - Prepare to meet with OUPD for the event. Written materials outlining needs, location, hours to work and responsibilities should be prepared. 3. Review Staff Assignments - In your meeting with site representatives and OUPD, review how many OUPD officers will be in place and their location. Review staff assignments and any supervisory responsibilities they will have. Provide, in writing, specific policies you have which would prohibit specific actions. Be certain to plan carefully for entrance and exit to event areas and by whom. Know who you will be contacting for specific problems and/or emergencies. Having access to immediate communication such as a cell phone or walkie-talkie is invaluable. Discuss how guest challenges will be handled. For example: Guest behavior will first be channeled through the administration and if severe will go to OUPD; sitting in restricted areas will go through the staff; and potential problems with guest location will work with staff and the administrators. 4. Written Emergency Plan - Prepare a written plan for emergency situations. Steps should be outlined in advance as to the procedures to be followed during the event of an emergency (i.e. -

Risk Management Biological Hazard Edition March 2015

AS/NZS 4801 OHSAS 18001 OHS20309 SAI Global Risk Management Biological Hazard Edition March 2015 Introduction activity. Primary controls are described in the top section of the hierarchy Monash University’s Victorian campuses are all governed by the Victorian and include Substitution, Isolation and Engineering. OHS Act 2004 and its subordinate regulations and codes of compliance. An Secondary controls assist the worker to be safer, in the case of inherent part of all OHS legislation is the requirement for workplaces to Administrative controls or act as the last layer of protection to those exposed control the hazards its activities may pose to the health and safety of staff, to the hazard in the case of Personal Protective Equipment. These are less visitors, contractors and students. reliable than primary controls, but still improve safety. This version of the Risk Management Program is designed to assist users There are many mandatory controls required by legislation and standards for identify hazards, assess the risk and determine the controls to reduce the research with biological material. These controls are provided for you risk associated with biological hazards. For general risk assessments, please convenience. see the Risk Management Program. The primary aim of the risk assessment process is to ensure the safety of all The occupational health and safety risks must be identified and eliminated tasks in the workplace. The end result of a risk assessment is the where possible or otherwise minimized. When the hazard cannot be implementation and maintenance of appropriate risk controls. eliminated, a combination of primary and secondary controls provides the safest option for reducing the risk of exposure to a hazard. -

Keep a Check – Health Surveillance and Risk Assessment Food and Drink Group Wednesday 6 September 2017

Keep a check – Health Surveillance and Risk Assessment Food and Drink Group Wednesday 6 September 2017 Julie Routledge – Occupational Health Manager Bit about me…. Worked in Occupational Health for 24 years . PG Diploma and Specialist Practitioner in Occupational Health obtained from University of Surrey . Mostly manufacturing – Weetabix, Mars Petcare, Perkins Diesel Engines and currently Greencore . Set up 2 OH services . Health Surveillance and Fit for Purpose medicals from beginning What is Health Surveillance • Health surveillance allows for early identification of ill health and helps identify any corrective action needed. • Health surveillance may be required by law if your employees are exposed to noise or vibration, solvents, fumes, dusts, biological agents and other substances hazardous to health, or work in compressed air. Source: HSE accessed 21/8/2017 http://www.hse.gov.uk/health- surveillance/index.htm So what do we need to consider Legislation for statutory requirements • Noise at work • Control of Substances Hazardous to Health • Manual Handling • Lead • Mercury • Asbestos • Vibration • Compressed Air • Radiation Fit for purpose screening What else/Fit for Purpose? Not a legal requirement but considered best practice • New starter Screening - baseline • Working Time Directives – Nightworker • Food Handlers • Drivers – Vocational and FLT etc • Working in Hot/Cold environments Health Risk Assessment • 5 steps to risk assessment • Identify the health hazard • Who is at risk from the health hazard • What are the current control -

Risk Analysis Draft May 2008

Update Project Chapter 2: Risk Analysis Draft May 2008 1 PRINCIPLES AND METHODS FOR THE RISK ASSESSMENT OF CHEMICALS IN FOOD 2 3 CHAPTER 2: RISK ANALYSIS 4 5 Contents 6 7 CHAPTER 2: RISK ANALYSIS............................................................................................1 8 2.1 INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................1 9 2.2 THE RISK ANALYSIS PARADIGM .........................................................................................1 10 2.2.1 Definitions of hazard and risk ...................................................................................2 11 2.2.2 Role of exposure assessment......................................................................................3 12 2.2.3 Interactions between risk assessment and risk management.....................................3 13 2.2.3.1 Problem formulation ...........................................................................................4 14 2.2.3.2 Priority setting for JECFA and JMPR ................................................................4 15 2.2.4 The role of risk assessment in risk analysis...............................................................4 16 2.2.4.1 Hazard identification...........................................................................................5 17 2.2.4.2 Hazard characterization ......................................................................................5 18 2.2.4.3 Exposure assessment...........................................................................................6 -

501 Adopted: 8 January 2007

OECD/OCDE 501 Adopted: 8 January 2007 OECD GUIDELINE FOR THE TESTING OF CHEMICALS Metabolism in Crops INTRODUCTION 1. The desired goal of a Metabolism in Crops study is the identification and characterisation of at least 90% of the total radioactive residue (TRR) in each raw agricultural commodity (RAC) of the treated crop. In many cases it may not be possible to identify significant portions of the TRRs especially when low total amounts of residue are present, when incorporated into biomolecules, or when the active ingredient is extensively metabolised to numerous low level components. In the latter case it is important for the applicants to demonstrate clearly the presence and levels of the components, and if possible, attempt to characterise them. 2. Metabolism in Crops studies are complex. The scientific techniques used to study xenobiotic metabolism and conjugate formation, isolation of plant macromolecules and procedures for generating monomers/oligomers, are constantly advancing. It is, therefore, the responsibility of the applicant to utilize state of the art techniques and provide citations of such techniques when used. PURPOSE 3. Studies of Metabolism in Crops are used to elucidate the degradation pathway of the active ingredient and require the identification of the metabolism and/or degradation products when a pesticide is applied to a crop directly or indirectly. 4. Studies of Metabolism in Crops fulfill several major purposes: − Provide an estimate of the total residues in the various RACs after crop treatment, which allows determination of the distribution of residues within the crop, e.g., whether the pesticide is absorbed through roots or foliage or whether translocation occurs; − Identify the major components of the terminal residue in the various RACs, thus indicating the components to be analysed for in residue quantification studies (i.e., the residue definition(s) for both risk assessment and enforcement). -

Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment

MODULE THREE Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment Learning Objective Upon completion of this unit you will understand how to identify hazards and assess risks for your dairy operation. Learner Outcomes: 1. Understand that behind each fatality or serious injury there are thousands of at-risk behaviors and unidentified hazards that contributed to the incident. 2. State the definition of a hazard and explain how to identify hazards in the workplace. Notes 3. Determine methods for controlling hazards in the workplace. _____________________ _____________________ 4. Complete a Job Hazard Analysis for a typical dairy worker task. _____________________ _____________________ _____________________ _____________________ _____________________ _____________________ _____________________ _____________________ _____________________ _____________________ _____________________ _____________________ _____________________ _____________________ Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment • Module 3 • 1 Introduction Safety in any operation works best if the person or people in charge take a leading role in managing safety and health. Notes Many business enterprises have proven that good safety ___________________ management leads to increased productivity, and the same works ___________________ for farms. ___________________ By having a good safety management program, you can avoid ___________________ not only farm injuries, but also other incidents that are costly, time ___________________ consuming, stressful and inconvenient. This makes good economic