Effective Risk Assessment in TA, JHA, JSA, JSEA, WMS, TAKE 5, and Incident Investigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Personal Protective Equipment Hazard Assessment

WORKER HEALTH AND SAFETY Personal Protective Equipment Hazard Assessment Oregon OSHA Personal Protective Equipment Hazard Assessment About this guide “Personal Protective Equipment Hazard Assessment” is an Oregon OSHA Standards and Technical Resources Section publication. Piracy notice Reprinting, excerpting, or plagiarizing this publication is fine with us as long as it’s not for profit! Please inform Oregon OSHA of your intention as a courtesy. Table of contents What is a PPE hazard assessment ............................................... 2 Why should you do a PPE hazard assessment? .................................. 2 What are Oregon OSHA’s requirements for PPE hazard assessments? ........... 3 Oregon OSHA’s hazard assessment rules ....................................... 3 When is PPE necessary? ........................................................ 4 What types of PPE may be necessary? .......................................... 5 Table 1: Types of PPE ........................................................... 5 How to do a PPE hazard assessment ............................................ 8 Do a baseline survey to identify workplace hazards. 8 Evaluate your employees’ exposures to each hazard identified in the baseline survey ...............................................9 Document your hazard assessment ...................................................10 Do regular workplace inspections ....................................................11 What is a PPE hazard assessment A personal protective equipment (PPE) hazard assessment -

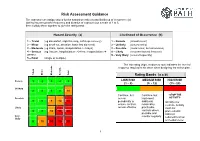

Risk Assessment Guidance

Risk Assessment Guidance The assessor can assign values for the hazard severity (a) and likelihood of occurrence (b) (taking into account the frequency and duration of exposure) on a scale of 1 to 5, then multiply them together to give the rating band: Hazard Severity (a) Likelihood of Occurrence (b) 1 – Trivial (eg discomfort, slight bruising, self-help recovery) 1 – Remote (almost never) 2 – Minor (eg small cut, abrasion, basic first aid need) 2 – Unlikely (occurs rarely) 3 – Moderate (eg strain, sprain, incapacitation > 3 days) 3 – Possible (could occur, but uncommon) 4 – Serious (eg fracture, hospitalisation >24 hrs, incapacitation >4 4 – Likely (recurrent but not frequent) weeks) 5 – Very likely (occurs frequently) 5 – Fatal (single or multiple) The risk rating (high, medium or low) indicates the level of response required to be taken when designing the action plan. Trivial Minor Moderate Serious Fatal Rating Bands (a x b) Remote 1 2 3 4 5 LOW RISK MEDIUM RISK HIGH RISK (1 – 8) (9 - 12) (15 - 25) Unlikely 2 4 6 8 10 Continue, but Continue, but -STOP THE Possible review implement ACTIVITY- 3 6 9 12 15 periodically to additional Identify new ensure controls reasonably controls. Activity Likely remain effective practicable must not controls where 4 8 12 16 20 proceed until possible and risks are Very monitor regularly reduced to a low likely 5 10 15 20 25 or medium level 1 Risk Assessments There are a number of explanations needed in order to understand the process and the form used in this example: HAZARD: Anything that has the potential to cause harm. -

Personal Protective Equipment ______

Personal Protective Equipment __________________________________________________________________ Page Introduction Purpose ………. 2 Background ………. 2 Who’s Covered? …….... 3 Explanation of Key Terms ………. 3 How It Works Hazard Assessment ………. 4 Hazard Control ………. 5 Training ………. 5 Documentation ………. 6 Appendix A – Hazard Assessment/Training Certification Form ………. 7 B – Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Guidelines ………. 8 University of Arizona Risk Management & Safety Health and Safety Instruction April 2007 ________________________________ Page 2 Health and Safety Instruction ______________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Purpose The purpose of this Health and Safety Instruction (HSI) is to protect employees from hazards in the workplace by using personal protective equipment to supplement other primary hazard controls. Background Hazards exist in every workplace in many different forms: sharp edges, falling objects, flying sparks, chemicals, noise and a myriad of other potentially dangerous situations. Controlling hazards with engineering and administrative controls is the best way to protect employees When these controls are not feasible or do not provide sufficient protection, personal protective equipment (PPE) must be use. In line with this rational for controlling or eliminating workplace hazards, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) issued the Personal Protective Equipment standard, also know as "The PPE Standard." Under this standard, the University is required to: • Conduct hazard assessments to determine if PPE is necessary to protect employees and certify in writing that assessments have been performed. • Select appropriate PPE, where necessary. • Provide employees training on proper care, use and limitations of the selected PPE. • Ensure the PPE is properly used. This HSI, developed by Risk Management & Safety outlines the minimum requirements to protect employees from hazards in the workplace by using personal protective equipment to supplement other primary hazard controls. -

Risk Management for a Small Business Participant Guide

Risk Management for a Small Business Participant Guide Table of Contents Welcome ................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 What Do You Know? Risk Management for a Small Business ........................................................................................ 4 Pre-Test .................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Risk Management ................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Discussion Point #1: Risks from Positive Situations .......................................................................................................... 6 Internal Risks ........................................................................................................................................................................ 6 Discussion Point #2: Internal Risks ..................................................................................................................................... 8 External Risks ....................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Discussion Point #3: External Risks ................................................................................................................................... -

Conducting a Job Safety Analysis to Eliminate Hazards

Practical Tips CONDUCTING A JOB SAFETY ANALYSIS TO ELIMINATE HAZARDS What is Job Safety Analysis? A job safety analysis (JSA) is a method for making your job safer. In a JSA, you do three things: 1. Observe step-by-step how a worker does an on-the-job task. 2. Look for possible hazards in each step of the task. 3. Suggest ways to eliminate or reduce each hazard so each step of the task is safer. A supervisor and typically two to three employees who know many steps involved in a job usually make up a JSA team. This number can vary depending on the complexity of the equipment or process. One employee can actually do the steps of the task. The others watch and write down on a JSA worksheet what they see. Performing the Job Safety Analysis Listing the Steps in the Task While one employee performs the task, the others watch and write down each step of the task. Keep the following tips in mind as you make the list in the first column of the JSA form: • List from 8 to 10 task steps that you can see. • Number each step. • List the steps in the order in which they are performed. • Use actions words such as "turn on," "load," "steer," or "unload." • Ask yourself, "What step starts this task?" List the first step, such as "put on PPE." • Then ask yourself, "What is the next basic step?" • List the next steps, such as "check that power is OFF" or "get into the operator's seat." • Tell completely but briefly what is done in each step, such as "lift the load and back out." Do not tell how the step is done, "lift the load with the fork slightly raised and back out slowly." • Continue in this way until you have listed every basic step in the task. -

Operational Risk Management Guide

OPERATIONAL RISK MANAGEMENT GUIDE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE 2020 Last Updated 02/26/2020 RISK MANAGEMENT COUNCIL IN COOPERATION WITH THE OFFICE OF SAFETY & OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH and THE NATIONAL AVIATION SAFETY COUNCIL Contents Contents ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................................. i Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................... 1 What is Operational Risk Management? ................................................................................................................... 1 The Terminology of ORM ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Principles of ORM Application ........................................................................................................................................... 6 The Five-Step ORM Process ................................................................................................................................................ 7 Step 1: Identify Hazards .................................................................................................................................................. -

Workplace Risk Management Practices to Prevent Musculoskeletal And

Safety Science 101 (2018) 220–230 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Safety Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/safety Workplace risk management practices to prevent musculoskeletal and MARK mental health disorders: What are the gaps? ⁎ Jodi Oakmana, , Wendy Macdonalda, Timothy Bartramb, Tessa Keegela,c, Natasha Kinsmana a Centre for Ergonomics and Human Factors, School of Psychology and Public Health, College of Science, Health & Engineering, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Victoria 3086, Australia b La Trobe Business School, Department of Management and Marketing, College of Arts, Social Sciences and Commerce (ASSC), La Trobe University, Bundoora, Victoria 3086, Australia c Monash Centre for Occupational and Environmental Health, School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Prahran, Victoria 3181, Australia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Introduction: A large body of evidence demonstrates substantial effects of work-related psychosocial hazards on Workplace risk management risks of both musculoskeletal and mental health disorders (MSDs and MHDs), which are two of the most costly Musculoskeletal occupational health problems in many countries. This study investigated current workplace risk management Psychosocial practices in two industry sectors with high risk of both MSDs and MHDs and evaluated the extent to which risk Occupational health and safety from psychosocial hazards is being effectively managed. Method: Nineteen, mostly large, Australian organisations were each asked to provide documentation -

Job Hazard Analysis

Job Hazard Analysis A Guide for Voluntary Compliance and Beyond This page intentionally left blank Job Hazard Analysis A Guide for Voluntary Compliance and Beyond From Hazard to Risk: Transforming the JHA from a Tool to a Process James E. Roughton Nathan Crutchfield AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Butterworth-Heinemann is an imprint of Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann is an imprint of Elsevier 30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP, UK Copyright © 2008, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science & Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: (+44) 1865 843830, fax: (+44) 1865 853333, E-mail: [email protected]. You may also complete your request online via the Elsevier homepage (http://elsevier.com), by selecting “Support & Contact” then “Copyright and Permission” and then “Obtaining Permissions.” Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, Elsevier prints its books on acid-free paper whenever possible. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roughton, James E. Job hazard analysis : a guide for voluntary compliance and beyond / James Roughton and Nathan Crutchfield. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7506-8346-3 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Industrial safety. I. Crutchfield, Nathan. II. Title. T55.R693 2007 658.38–dc22 2007033646 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Hot Work Permit Program

Hot Work Permit Program Risk Management 1 Hot Work Permit Program Risk Management July 2019 Table of Contents I. Program Goals and Objectives ...................................................................................................................3 II. Scope and Application ................................................................................................................................3 III. Definitions ..................................................................................................................................................3 IV. Responsibilities ...........................................................................................................................................4 V. Record Keeping ..........................................................................................................................................4 VI. Procedures .................................................................................................................................................5 VII. Hot Work Permit Form ...............................................................................................................................8 VIII. Regulatory Authority and Related Information .........................................................................................9 IX. Contact .......................................................................................................................................................9 2 Hot Work Permit Program Risk Management -

Guide Six Steps to Risk Management

Guide Six step to risk management www.worksafe.nt.gov.au Disclaimer This publication contains information regarding work health and safety. It includes some of your obligations under the Work Health and Safety (National Uniform Legislation) Act – the WHS Act – that NT WorkSafe administers. The information provided is a guide only and must be read in conjunction with the appropriate legislation to ensure you understand and comply with your legal obligations. Acknowledgement This guide is based on material produced by WorkSafe ACT at www.worksafe.act.gov.au Version: 1.2 Publish date: September 2018 Contents Introduction ..............................................................................................................................4 Good management practice.....................................................................................................4 Defining Hazard and Risk.....................................................................................................5 Systematic approach to the management of Hazards and associated Risks ......................5 Step 1: Hazard identification ....................................................................................................6 Examples of Hazards ...........................................................................................................6 Step 2: Risk identification.........................................................................................................7 Examples of risk identification ..............................................................................................7 -

Permit to Work Systems

Loss prevention standards Permit to Work Systems High risk work can become even more hazardous due to unsafe conditions and human error. Formal controls, such as a permit to work system, must be followed by everyone and enforced properly to be effective. Aviva: Public Permit to Work Systems Introduction The aim of a permit to work system is to remove both unsafe conditions and human error from a high-risk process, by imposing a formal system detailing exactly what work is to be done and when and how to undertake the job safely. Permit to work systems are used where the potential hazards are significant and a formal documented system is required to control the work and minimise the risk of personal injury, loss or damage. Operation of the Permit to Work System Examples of work in which a permit to work system should be used include: • Entry into confined spaces • Work involving the splitting or breaking into of pressurised pipelines • Work on high voltage electrical systems above 3,000 volts • Hot work, e.g. welding, brazing, soldering, etc. • Work in isolated situations or where access is difficult • Work at height • Work near to, or requiring the use of highly flammable/explosive/toxic substances • Fumigation operations using gases • High-risk operations involving contractors, such as excavation works, or demolition works Designing the Permit to Work System Permit to work systems demand robust, formal and effective controls in place to prevent danger, as well as good standards of organisation to ensure compliance. - include fire extinguishers being available for hot work, or harnesses and resuscitation equipment available when entering confined spaces. -

Safety Manual

Eastern Elevator Safety and Health Manual January 2017 Page 1 of 125 SAFETY AND HEALTH MANUAL Index by Section Number Safety Policy ................................................................................................................. …4 Section 1: General Health and Safety Policies ............................................................. …5 Section 2: Hazard Communication ................................................................................ ..13 Section 3: Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) ......................................................... ..18 Section 4: Emergency Action Plan ................................................................................ ..31 Section 5: Fall Protection .............................................................................................. ..34 Section 6: Ladder Safety ............................................................................................... ..38 Section 7: Bloodborne Pathogens ................................................................................ ..42 Section 8: Motor Vehicle / Fleet Safety ......................................................................... ..47 Section 9: Hearing Conservation .................................................................................. ..50 Section 10: Lockout / Tagout ........................................................................................ ..53 Section 11: Fire Prevention ..........................................................................................