Excess Deaths Associated with Covid-19 Pandemic in 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Publications Using the HMD in Years 1997 – 2013

Publications Using the HMD in Years 1997 – 2013 Table of Contents Official Reports ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Books and Book Chapters .............................................................................................................................. 4 Journal Articles ................................................................................................................................................ 12 Dissertations and Theses .............................................................................................................................. 63 Technical Reports, Working, Research and Discussion Papers ......................................................... 67 Introduction The following comprises a list of publications that rely on data from the Human Mortality Database. It resorts to the Google Scholar web search engine1 using “Human mortality database” and “Berkeley mortality database” as the search expressions. The expressions may appear anywhere in the publication (title, abstract, body). Works that used the BMD are identified by “[BMD]” at the end of the citation; all other publications used the HMD. This version of the HMD reference list concentrates on scholarly articles and books, dissertations, technical reports and working papers published from January 1997 up to the end of November 2013. The list also includes all publications by the HMD team members based on analyses of -

Appendix 2: Publications and Other Works Using Data from the Human

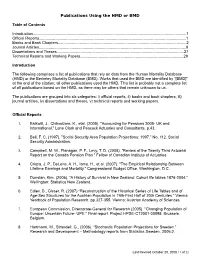

Publications Using the HMD or BMD Table of Contents Introduction.............................................................................................................................................1 Official Reports.......................................................................................................................................1 Books and Book Chapters......................................................................................................................2 Journal Articles.......................................................................................................................................8 Dissertations and Theses.....................................................................................................................27 Technical Reports and Working Papers...............................................................................................29 Introduction The following comprises a list of publications that rely on data from the Human Mortality Database (HMD) or the Berkeley Mortality Database (BMD). Works that used the BMD are identified by “[BMD]” at the end of the citation; all other publications used the HMD. This list is probably not a complete list of all publications based on the HMD, as there may be others that remain unknown to us. The publications are grouped into six categories: i) official reports, ii) books and book chapters, iii) journal articles, iv) dissertations and theses, v) technical reports and working papers. Official Reports 1. Balkwill, -

Program Third HMD Symposium Expanding the Human Mortality Database: Data by Cause and by Region

4 Appendix 1 – Scientific program Third HMD Symposium Expanding the Human Mortality Database: Data by Cause and by Region THURSDAY, JUNE 17, 2010 9:30 am – 10:00 am Introduction Chantal Cases – Director of INED Vladimir Shkolnikov – Co-Director of HMD, MPIDR John Wilmoth – Co-Director of HMD, UC Berkeley 10:30 am – 11:15 pm I. –Extending the HMD to include cause-of-death data Expanding the HMD to include cause-of-death data Magali Barbieri (INED, France, and UC Berkeley, United States) and Carl Boe (UC Berkeley, United States) Comparing cause specific mortality over time and across countries: An overview of methodological issues France Meslé (INED, France) and Jacques Vallin (INED, France) 11:30 am – 1:00 pm II. -Constructing series of deaths by cause: Methodological issues Comparability issues observed in the reconstructed time series of three European countries Markéta Pechholdová (Charles University, Czech Republic) A mathematical approach for detecting and correcting structural changes in time series of causes of death Ronald van der Stegen (Beusichem, The Netherlands), Fanny Janssen (University of Groningen, The Netherlands), Peter Harteloh, Jan Kardaun, and Wiet Koren. Provisional plan for the Japanese Mortality Database and its cause-of-death data Futhoshi Ishii (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, Japan) Discussant: Géraldine Duthé (INED, France) 2:00 pm – 4:00 pm III - Constructing series of deaths by cause: Applications and data analysis Producing cause-of-death statistics in Italy: State of the art -

Demographic Responses to Economic and Environmental Crises

Demographic Responses to Economic and Environmental Crises Edited by Satomi Kurosu, Tommy Bengtsson, and Cameron Campbell Proceedings of the IUSSP Seminar May 21-23, 2009, Reitaku University Kashiwa, Japan, 2010 Reitaku University Copyright 2010 Authors of this volume No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the authors Reitaku University Hikarigaoka 2-1-1, Kashiwa, Chiba 277-8686 Japan ii Preface This volume is the proceedings of the IUSSP (International Union for the Scientific Study of Population) seminar on “Demographic Responses to Sudden Economic and Environmental Change.” The seminar took place in Kashiwa, Chiba, Japan, May 21- 23, 2009. The fourteen papers presented at the seminar are included in this volume. The seminar was followed by a public symposium “Lessons from the Past: Climate, Disease, and Famine” in which five participants of the seminar presented and discussed issues related to the seminar to an audience that included 245 scholars, students and members of the public. Two additional papers presented at the symposium are also included in this volume. The seminar was organized by the IUSSP Scientific Panel on Historical Demography and hosted by Reitaku University. The seminar received support from Reitaku University and was held in cooperation with the Centre for Economic Demography, Lund University and the Population Association of Japan. The public symposium was organized as part of a series of events to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Reitaku University. The topic of the seminar was timely not only in the academic sense, but also in a practical sense, with the simultaneous worldwide outbreak of H1N1 flu. -

Effect of the Covid-19 Pandemic in 2020 on Life Expectancy BMJ: First Published As 10.1136/Bmj.N1343 on 23 June 2021

RESEARCH Effect of the covid-19 pandemic in 2020 on life expectancy BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.n1343 on 23 June 2021. Downloaded from across populations in the USA and other high income countries: simulations of provisional mortality data Steven H Woolf,1 Ryan K Masters,2 Laudan Y Aron3 1Center on Society and Health, ABSTRACT decreased by 1.87 years (to 76.87 years), 8.5 times Virginia Commonwealth OBJECTIVE the average decrease in peer countries (0.22 years), University School of Medicine, To estimate changes in life expectancy in 2010-18 widening the gap to 4.69 years. Life expectancy in Richmond, VA, USA and during the covid-19 pandemic in 2020 across the US decreased disproportionately among racial 2Department of Sociology, Health and Society Program and population groups in the United States and to and ethnic minority groups between 2018 and Population Program, Institute of compare outcomes with peer nations. 2020, declining by 3.88, 3.25, and 1.36 years in Behavioral Science, University Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic of Colorado Population Center, DESIGN University of Colorado Boulder, Simulations of provisional mortality data. White populations, respectively. In Hispanic and CO, USA non-Hispanic Black populations, reductions in life SETTING 3Urban Institute, Washington, expectancy were 18 and 15 times the average in US and 16 other high income countries in 2010- DC, USA peer countries, respectively. Progress since 2010 in 18 and 2020, by sex, including an analysis of US Correspondence to: S H Woolf reducing the gap in life expectancy in the US between outcomes by race and ethnicity. -

Human Mortality Database (HMD) Example of Country Data Page As of May 2012 the Database Contains Detailed Celebrates Its 10Th Anniversary

Research Team Acknowledgements University of California, Berkeley This project would not have been possible without the John Wilmoth (Director) enthusiasm and assistance of a large number of individuals Magali Barbieri (Project Coordinator) at various institutions. Demographers and statisticians Carl Boe from around the world have contributed to this project by Nadine Ouellette supplying data and/or expert advice for a particular country Timothy Riffe or area. We are grateful for all their contributions. Celeste Winant 3GDÄ',#ÄQDBDHUDRÄÆÄM@MBH@KÄ@MCÄKNFHRSHB@KÄRTOONQSÄEQNLÄ Lisa Yang its two sponsoring institutions, the Department of Mila Andreeva (Rockefeller University, USA) Demography at the University of California, Berkeley (UCB) and the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research ,/(#1 Ä3GDÄ4"!ÄSD@LÄQDBDHUDRÄÆÄM@MBH@KÄRTOONQSÄEQNLÄ Vladimir Shkolnikov (Co-Director) SGDÄ-@SHNM@KÄ(MRSHSTSDÄNMÄ FHMFÄ-( Ä@MCÄADMDÆÄSRÄEQNLÄSGDÄ Dmitri Jdanov supportive infrastructure of the NIA-funded Center on the Domantas Jasilionis Economics and Demography of Aging (CEDA) at UCB. Pavel Grigoriev Sigrid Gellers-Barkmann Evgueni Andreev (New Economic School, Russia) Human Contact Former members of the core HMD team Mortality Dana Glei (Georgetown University, USA) E-mail: [email protected] Kirill Andreev (United Nations) Database Vladimir Canudas-Romo (Johns Hopkins University, USA) Department of Demography www.mortality.org at the University Others who have worked for this project in of California University of California, Berkeley (UCB) the past include: 10 years of work for the international Leo Deegan, Carolyn Hart, Marguerite Higa, 2232 Piedmont Ave Romano Lasker, Marian Rigney-Hawksworth, Berkeley, CA 94720-2120 RBHDMSHÆÄBÄBNLLTMHSX Pierre Vachon, Long Wang, Lijing Yan (all UCB), http://www.demog.berkeley.edu Michael Bubenheim, Rembrandt Scholz, Guiping Liu, Dimiter Philipov, Eva Kibele (all MPIDR). -

Women Live Longer Than Men Even During Severe Famines and Epidemics

Women live longer than men even during severe PNAS PLUS famines and epidemics Virginia Zarullia,b, Julia A. Barthold Jonesa,b, Anna Oksuzyanc, Rune Lindahl-Jacobsena,b, Kaare Christensena,b,d,e, and James W. Vaupela,b,f,g,1 aMax Planck Odense Center on the Biodemography of Aging, University of Southern Denmark, DK-5230 Odense, Denmark; bDepartment of Public Health, University of Southern Denmark, DK-5000 Odense, Denmark; cMax Planck Research Group Gender Gaps in Health and Survival, Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, 18057 Rostock, Germany; dDepartment of Clinical Genetics, Odense University Hospital, DK-5000 Odense, Denmark; eDepartment of Clinical Biochemistry and Pharmacology, Odense University Hospital, DK-5000 Odense, Denmark; fMax Planck Institute for Demographic Research, 18057 Rostock, Germany; and gDuke University Population Research Institute, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708 Contributed by James W. Vaupel, November 22, 2017 (sent for review February 6, 2017; reviewed by Tommy Bengtsson and France Mesle) Women in almost all modern populations live longer than men. conditions is sparse. A well-known story concerns the Donner Research to date provides evidence for both biological and social Party, a group of settlers that lost twice as many men as women factors influencing this gender gap. Conditions when both men when stranded for 6 mo in the extreme winter in the Sierra and women experience extremely high levels of mortality risk are Nevada mountains (13). While accounts like this are anecdotal, a unexplored sources of information. We investigate the survival of variety of studies provide evidence that women appear to survive both sexes in seven populations under extreme conditions from cardiovascular diseases, cancers, and disabilities longer than men famines, epidemics, and slavery. -

Official Population Statistics and the Human Mortality Database Estimates of Populations Aged 80+ in Germany and Nine Other European Countries

Demographic Research a free, expedited, online journal of peer-reviewed research and commentary in the population sciences published by the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research Konrad-Zuse Str. 1, D-18057 Rostock · GERMANY www.demographic-research.org DEMOGRAPHIC RESEARCH VOLUME 13, ARTICLE 14, PAGES 335-362 PUBLISHED 17 NOVEMBER 2005 http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol13/14/ DOI: 10.4054/DemRes.2005.13.14 Descriptive Finding Official population statistics and the Human Mortality Database estimates of populations aged 80+ in Germany and nine other European countries Dmitri A. Jdanov Rembrandt D. Scholz Vladimir M. Shkolnikov This article is part of Demographic Research Special Collection 4, “Human Mortality over Age, Time, Sex, and Place: The 1st HMD Symposium”. Please see Volume 13, publications 13-10 through 13-20. © 2005 Max-Planck-Gesellschaft. Table of Contents 1 Introduction 336 2 Methods and data 338 2.1 Methods for re-estimation of the population size at ages 80+. A 338 brief summary of HMD methodology 2.1.1 Re-estimations of populations 338 2.1.2 Quality of data on deaths 341 2.2 Country data series 342 3 German population estimates since 1956 344 4 A comparison of the population estimates since 1950 for other 351 countries 5 Absolute differences 352 6 Factors of deviation from the HMD estimates 356 7 Summary of findings and discussion 358 References 360 Demographic Research: Volume 13, Article 14 descriptive finding Official population statistics and the Human Mortality Database estimates of populations aged 80+ in Germany and nine other European countries Dmitri A. Jdanov 1 Rembrandt D. -

WHO Methods and Data Sources for Life Tables 1990-2016

WHO methods and data sources for life tables 1990-2016 Department of Information, Evidence and Research WHO, Geneva March 2018 Global Health Estimates Technical Paper WHO/HIS/IER/GHE/2018.2 Acknowledgments This Technical Report was written by Colin Mathers and Jessica Ho with inputs and assistance from Dan Hogan, Wahyu Retno Mahanani, Doris Ma Fat and Gretchen Stevens. WHO life tables were primarily prepared by Jessica Ho and Colin Mathers of the Mortality and Health Analysis Unit in the WHO Department of Information, Evidence and Research (in the Health Systems and Innovation Cluster of WHO, Geneva). Data and methods used for this update of life tables were developed with advice and assistance from a WHO Lifetables Working Group, established by the WHO Reference Group on Global Health Statistics. We also drew on advice and inputs from the Interagency Group on Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME), the UN Population Division, UNICEF and UNAIDS. We would particularly like to note the assistance and inputs provided by Patrick Gerland, Bruno Masquelier, Francois Pelletier, Danzhen You and Lucia Hug. Estimates and analysis are available at: http://www.who.int/gho/mortality_burden_disease/en/index.html http://www.who.int/gho For further information about the estimates and methods, please contact [email protected] Recent papers in this series 1. CHERG-WHO methods and data sources for child causes of death 2000-2015 (Global Health Estimates Technical Paper WHO/HIS/HSI/GHE/2016.1) 2. WHO methods and data sources for life tables 1990-2015 (Global Health Estimates Technical Paper WHO/HIS/IER/GHE/2016.2) 3. -

Human Mortality Over Age, Time, Sex, and Place: the 1St HMD Symposium”

Demographic Research a free, expedited, online journal of peer-reviewed research and commentary in the population sciences published by the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research Konrad-Zuse Str. 1, D-18057 Rostock · GERMANY www.demographic-research.org DEMOGRAPHIC RESEARCH VOLUME 13, ARTICLE 10, PAGES 223-230 PUBLISHED 17 NOVEMBER 2005 http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol13/10/ DOI: 10.4054/DemRes.2005.13.10 Summary Introduction to the Special Collection “Human Mortality over Age, Time, Sex, and Place: The 1st HMD Symposium” Vladimir M. Shkolnikov John R. Wilmoth Dana A. Glei This article is part of Demographic Research Special Collection 4, “Human Mortality over Age, Time, Sex, and Place: The 1st HMD Symposium”. Please see Volume 13, publications 13-10 through 13-20. © 2005 Max-Planck-Gesellschaft. Table of Contents 1 The Human Mortality Database 224 2 The HMD Symposium 225 3 Summary of the articles 225 4 Acknowledgements 229 References 230 Demographic Research: Volume 13, Article 10 a summary Introduction to the Special Collection “Human Mortality over Age, Time, Sex, and Place: The 1st HMD Symposium” Vladimir M. Shkolnikov 1 John R. Wilmoth 2 Dana A. Glei 3 Abstract This introduction to the special collection “Human Mortality over Age, Time, Sex, and Place: The 1st HMD Symposium” describes the Human Mortality Database project and briefly summarizes the Special Collection articles. This article is part of Demographic Research Special Collection 4, “Human Mortality over Age, Time, Sex, and Place: The 1st HMD Symposium”. Please see Volume 13, Publications 13-10 through 13-20. 1 Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Rostock, Germany E-mail: [email protected] 2 United Nations Population Division (on leave from the University of California, Berkeley) E-mail: [email protected] 3 University of California, Berkeley; 1512 Pembleton Place, Santa Rosa, CA, 95403-2349, USA. -

Universidade Federal De Minas Gerais Centro De Desenvolvimento E Planejamento Regional Programa De Pós-Graduação Em Demografia

Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais Centro de Desenvolvimento e Planejamento Regional Programa de Pós-Graduação em Demografia VANGUARDS OF LONGEVITY: THE CASE OF BRAZILIAN AIR FORCE MILITARY Vanessa Gabrielle di Lego Gonçalves Belo Horizonte 2017 Ficha Catalográfica Gonçalves, Vanessa Gabrielle di Lego. G635v Vanguards of longevity [manuscrito] : the case of brazilian Air 2017 Force military / Vanessa Gabrielle di Lego Gonçalves – 2017. 72 f.: il., gráfs. e tabs. Orientador: Cássio M. Turra. Tese (doutorado) - Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Centro de Desenvolvimento e Planejamento Regional. Inclui bibliografia (f. 53-64). 1. Mortalidade - Militares - Brasil - Teses. 2. Longevidade - Teses 3. Demografia - Teses. I. Turra, Cássio Maldonado. II. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Centro de Desenvolvimento e Planejamento Regional. III. Título. CDD: 338.473621981 Elaborada pela Biblioteca da FACE/UFMG – JN001/2018 Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais Faculdade de Ciências Econômicas Centro de Desenvolvimento e Planejamento Regional Vanguards of Longevity: The case of Brazilian Air Force military Vanessa Gabrielle di Lego Gonçalves Tese submetida à banca examinadora designada pelo Colegiado do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Demografia da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, como parte dos requisi- tos necessários à obtenção do grau de Doutora em Demografia. Orientador: Prof. Cássio M. Turra, PhD Belo Horizonte, Dezembro de 2017 Abstract In the demographic study of mortality, there has been growing attention to population subgroups that are more likely to first benefit from mortality progress or benefit more intensively than others. Some authors define these subgroups as “vanguard” populations (Evgueni et al. 2014; Caselli and Luy 2014). Focusing on mortality trajectories of vanguard populations can be instrumental to disentangling the pathways to longer lives and isolating specific risk factors (Evgueni et al. -

2017 09 29 LRQ IUSSP DDM.Pdf Final Paper

An evaluation of adult death registration coverage in the Human Mortality Database and World Health Organization mortality data. Everton Lima Universidade Estadual de Campinas – Unicamp [email protected] Tim Riffe Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research [email protected] Bernardo Queiroz Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais [email protected] Lara Takigava Acrani. Universidade Estadual de Campinas – Unicamp [email protected] Abstract The Human Mortality Database (HMD) and the World Health Organization Global Health Observatory (GHO) are important mortality databases to study the evolution of mortality and health conditions around the world. The HMD is considered to be the highest quality standardized mortality database, while the GHO is as extensive mortality database of primary (unadjusted) data provided to WHO by member states. Many studies use HMD data to investigate the trends in life expectancy, distribution of age at death, and others. In addition, several studies evaluate the quality of data. GHO is not subject to any procedures to control the data quality, and one important limitation is under-registration of death counts, especially in countries with incomplete vital registration systems. Furthermore, the issue of under-registration of death counts is not discussed for HMD, as countries are selected for inclusion on the premise that vital registration is nearly complete. We use a set of formal demographic analyses, based on the Death Distribution Methods (DDM), to evaluate the quality of mortality data for all countries in these two databases. The results indicate that quality of mortality data is improving over time for most countries in the world. We also find that a series of HMD countries have low completeness of death count registration, and some countries have significant variations in data quality in specific periods, in general related to social, economic, or political instability.