Silesian Administrative Authorities and Territorial Transformations of Silesia (1918-1945)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Oder-Neisse Line As Poland's Western Border

Piotr Eberhardt Piotr Eberhardt 2015 88 1 77 http://dx.doi.org/10.7163/ GPol.0007 April 2014 September 2014 Geographia Polonica 2015, Volume 88, Issue 1, pp. 77-105 http://dx.doi.org/10.7163/GPol.0007 INSTITUTE OF GEOGRAPHY AND SPATIAL ORGANIZATION POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES www.igipz.pan.pl www.geographiapolonica.pl THE ODER-NEISSE LINE AS POLAND’S WESTERN BORDER: AS POSTULATED AND MADE A REALITY Piotr Eberhardt Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization Polish Academy of Sciences Twarda 51/55, 00-818 Warsaw: Poland e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article presents the historical and political conditioning leading to the establishment of the contemporary Polish-German border along the ‘Oder-Neisse Line’ (formed by the rivers known in Poland as the Odra and Nysa Łużycka). It is recalled how – at the moment a Polish state first came into being in the 10th century – its western border also followed a course more or less coinciding with these same two rivers. In subsequent cen- turies, the political limits of the Polish and German spheres of influence shifted markedly to the east. However, as a result of the drastic reverse suffered by Nazi Germany, the western border of Poland was re-set at the Oder-Neisse Line. Consideration is given to both the causes and consequences of this far-reaching geopolitical decision taken at the Potsdam Conference by the victorious Three Powers of the USSR, UK and USA. Key words Oder-Neisse Line • western border of Poland • Potsdam Conference • international boundaries Introduction districts – one for each successor – brought the loss, at first periodically and then irrevo- At the end of the 10th century, the Western cably, of the whole of Silesia and of Western border of Poland coincided approximately Pomerania. -

The Case of Upper Silesia After the Plebiscite in 1921

Celebrating the nation: the case of Upper Silesia after the plebiscite in 1921 Andrzej Michalczyk (Max Weber Center for Advanced Cultural and Social Studies, Erfurt, Germany.) The territory discussed in this article was for centuries the object of conflicts and its borders often altered. Control of some parts of Upper Silesia changed several times during the twentieth century. However, the activity of the states concerned was not only confined to the shifting borders. The Polish and German governments both tried to assert the transformation of the nationality of the population and the standardisation of its identity on the basis of ethno-linguistic nationalism. The handling of controversial aspects of Polish history is still a problem which cannot be ignored. Subjects relating to state policy in the western parts of pre-war Poland have been explored, but most projects have been intended to justify and defend Polish national policy. On the other hand, post-war research by German scholars has neglected the conflict between the nationalities in Upper Silesia. It is only recently that new material has been published in England, Germany and Poland. This examined the problem of the acceptance of national orientations in the already existing state rather than the broader topic of the formation and establishment of nationalistic movements aimed (only) at the creation of a nation-state.1 While the new research has generated relevant results, they have however, concentrated only on the broader field of national policy, above all on the nationalisation of the economy, language, education and the policy of changing names. Against this backdrop, this paper points out the effects of the political nationalisation on the form and content of state celebrations in Upper Silesia in the following remarks. -

Legacy of Religious Identities in the Urban Space of Bielsko-Biała

PRaCE GEOGRaFiCznE, zeszyt 137 instytut Geografii i Gospodarki Przestrzennej UJ Kraków 2014, 137 – 158 doi : 10.4467/20833113PG.14.013.2158 Legacy of reLigious identities in the urban space of bieLsko-biała Emilia Moddelmog-Anweiler Abstract : Religious heritage is an important cultural resource for a city. First, cities are at the crossroads of conflicting trends in globalisation. Urban communities are looking for that which makes them universal and unique at the same time. Second, reflection on identity in relation to the heritage and history of a city reveals the multicultural past of Central and Eastern Europe, and shows an image of social change and transformation. Religious heritage plays, therefore, various roles. Places connected with religious identities have symbolic, sacred and artistic meanings. They construct a local universe of meaning ; they are an important factor of the local narrative and customs, and they place it in the context of national, regional and ethnic traditions. Churches, temples, and cemeteries are also a sign of memory, this shows not only history but also the contemporary processes of remember- ing and forgetting. The city of Bielsko-Biała was a cultural and religious mosaic until 1945. Jewish, German and Polish cultures were meeting here everyday with diverse religious belonging and boundaries. Today, the heritage of its religious identity is recognized mainly via monuments, tourist attractions, and cultural events. Only occasionally is the religious heritage of the city analysed in the context of collective identities. Urban space still reflects the complexity of the relationships between religious, national, and regional identities. The purpose of the paper is to describe the variety of functions of religious heritage in a contemporary city on the example of Bielsko-Biała in Poland. -

Uneeveningseveralyearsago

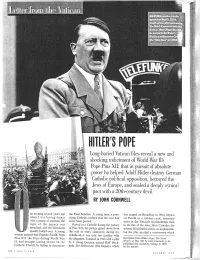

SUdfffiiUeraiKdiesavadio speechfinWay9,3934, »eariya3fearjafierannounce !Uie9leich£oncoRlati^3he Vatican.Aisei^flope^us )isseamed^SLIRetef^ Sa^caonVeconber ahe*»otyireaf'4Dfl9ra: 'i ' TlfraR Long-buried Vatican files reveal a new anc ; shocking indictment of World War IPs Jj; : - I • • H.t.-,. in n. ; Pope Pius XII: that in pursuit of absolute power he helped Adolf Hitler destroy German ^ Catholic political opposition, betrayed the Europe, and sealed a deeply cynica pact with a 20th-century devi!. BBI BY JOHN CORNWELL the Final Solution. A young man, a prac was staged on Broadway in 1964. depict UnewheneveningI wasseveralhavingyearsdinnerago ticing Catholic, insisted that the case had ed Pacelli as a ruthless cynic, interested with a group of students, the never been proved. more in the Vatican's stockholdings than topic of the papacy was Raised as a Catholicduring the papacy in the fate of the Jews. Most Catholics dis broached, and the discussion of Pius XII—his picture gazed down from missed Hochhuth's thesis as implausible, quickly boiled over. A young the wall of every classroom during my but the play sparked a controversy which woman asserted that Eugenio Pacelli, Pope childhood—I was only too familiar with Pius XII, the Pope during World War the allegation. It started in 1963 with a play Excerpted from Hitler's Pope: TheSeci-et II, had brought lasting shame on the by a young German named Rolf Hoch- History ofPius XII. bj' John Comwell. to be published this month byViking; © 1999 Catholic Church by failing to denounce huth. DerStellverti-eter (The Deputy), which by the author. VANITY FAIR OCTOBER 1999 having reliable knowl- i edge of its true extent. -

Breslau Or Wrocław? the Identity of the City in Regards to the World War II in an Autobiographical Reflection

DEBATER A EUROPA Periódico do CIEDA e do CEIS20 , em parceria com GPE e a RCE. N.13 julho/dezembro 2015 – Semestral ISSN 1647-6336 Disponível em: http://www.europe-direct-aveiro.aeva.eu/debatereuropa/ Breslau or Wrocław? The identity of the city in regards to the World War II in an autobiographical reflection Anna Olchówka University of Wrocław E-mail: [email protected] Abstract On the 1st September 1939 a German city Breslau was found 40 kilometers from the border with Poland and the first front lines. Nearly six years later, controlled by the Soviets, the city came under the "Polish administration" in the "Recovered Territories". The new authorities from the beginning virtually denied all the past of the city, began the exchange of population and the gradual erasure of multicultural memory; the heritage of the past recovery continues today. The main objective of this paper is to present the complexity of history through episodes of a city history. The analysis of texts and images, biographies of the inhabitants / immigrants / exiles of Breslau / Wrocław and the results of modern research facilitate the creation of a complex political, economic, social and cultural landscape, rewritten by historical events and resettlement actions. Keywords: Wrocław; Breslau; identity; biography; history Scientific meetings and conferences open academics to new perspectives and face them against different opinions, arguments, works and experiences. The last category, due to its personal and individual aspect, is very special. Experience can be shared and gained at the same time, which is inherent to the continuous development of human beings. Because of its subjectivity, experiences often pose a great methodological problem for the humanistic studies. -

The Historical Cultural Landscape of the Western Sudetes. an Introduction to the Research

Summary The historical cultural landscape of the western Sudetes. An introduction to the research I. Introduction The authors of the book attempted to describe the cultural landscape created over the course of several hundred years in the specific mountain and foothills conditions in the southwest of Lower Silesia in Poland. The pressure of environmental features had an overwhelming effect on the nature of settlements. In conditions of the widespread predominance of the agrarian economy over other categories of production, the foot- hills and mountains were settled later and less intensively than those well-suited for lowland agriculture. This tendency is confirmed by the relatively rare settlement of the Sudetes in the early Middle Ages. The planned colonisation, conducted in Silesia in the 13th century, did not have such an intensive course in mountainous areas as in the lowland zone. The western part of Lower Silesia and the neighbouring areas of Lusatia were colonised by in a planned programme, bringing settlers from the German lan- guage area and using German legal models. The success of this programme is consid- ered one of the significant economic and organisational achievements of Prince Henry I the Bearded. The testimony to the implementation of his plan was the creation of the foundations of mining and the first locations in Silesia of the cities of Złotoryja (probably 1211) and Lwówek (1217), perhaps also Wleń (1214?). The mountain areas further south remained outside the zone of intensive colonisation. This was undertak- en several dozen years later, at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, and mainly in the 14th century, adapting settlement and economy to the special conditions of the natural environment. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

Poland's Voivodeships and Poviats and the Geographies Of

Prace Komisji Geografii Przemysłu Polskiego Towarzystwa Geograficznego Studies of the Industrial Geography Commission of the Polish Geographical Society 30 (2) · 2016 UniversityStanley of Kentucky,D. Brunn Lexington, USA CracowMarcin University Semczuk of Economics, Poland PedagogicalRafał Koszek, UniversityPoland’s Karolinaof VoivodeshipsCracow, Poland Gołuszka, and Poviats Gabriela and the Bołoz Geographies of Knowledge: Addressing Uneven Human Resources Abstract: - - In a postindustrial economic world, information economies are key components in local, region al and national development. These are service economies, built on the production, consumption and dis semination of information, including education, health care, outsourcing, tourism, sustainability and related- perlinkshuman welfare are electronic services. knowledge We explore data the that geography/knowledge can be mapped to highlight intersections the areas in Poland’sof most and voivodeships least informa and- poviats by using the volumes of information or hyperlinks about selected information economies. Google hy tion about certain subject categories. While some mapping results are expected, such as Warsaw and Krakow, being prominent, in other regions there are unexpected gaps within eastern, northern and southern Poland,- including some places near major metropolitan centers. There is a significant difference between the cities with poviat rights, which stand out in the number of information on items comparing to the poviats that sur round them. The majority of poviats in Mazowieckie voivodeship are surprisingly recognized as core areas onKeywords: the map of knowledge, nevertheless they are considered undeveloped from the economic point of view. Received: Google hyperlinks; human welfare; knowledge economies; knowledge gaps Accepted: 13 January 2016 Suggested 6citation: June 2016 Prace Komisji Geografii przemy- słuBrunn, Polskiego S.D., Semczuk, Towarzystwa M., Koszek, Geograficznego R., Gołuszka, [Studies K., Bołoz of the G. -

Sifting Poles from Germans? Ethnic Cleansing and Ethnic Screening In

Sifting Poles from Germans? Ethnic Cleansing and Ethnic Screening in Upper Silesia, 1945–1949 Author(s): HUGO SERVICE Reviewed work(s): Source: The Slavonic and East European Review, Vol. 88, No. 4 (October 2010), pp. 652-680 Published by: the Modern Humanities Research Association and University College London, School of Slavonic and East European Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41061897 . Accessed: 25/08/2012 13:48 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Modern Humanities Research Association and University College London, School of Slavonic and East European Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Slavonic and East European Review. http://www.jstor.org SEER, Vol. 88, No. 4, October2010 SiftingPoles fromGermans? Ethnic Cleansingand EthnicScreening in Upper Silesia,1 945-1 949 HUGO SERVICE I The ethniccleansing which engulfedCentral and EasternEurope in the firsthalf of the twentiethcentury was oftena matterof indiscrimi- nate expulsionin whichlittle or no timewas takento reflecton the culturalidentity of the victims.Yet not all of it was carriedout in this manner.The occupiersand governmentswhich implementedethnic cleansingpolicies in Poland and Czechoslovakiaduring and afterthe Second World War came to the conclusionthat there were many inhabitantsof the territoriesthey wished to 'cleanse' who could not be instantlyrecognized as belongingto one nationalgroup or another. -

Local Expellee Monuments and the Contestation of German Postwar Memory

To Our Dead: Local Expellee Monuments and the Contestation of German Postwar Memory by Jeffrey P. Luppes A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Germanic Languages and Literatures) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor Andrei S. Markovits, Chair Professor Geoff Eley Associate Professor Julia C. Hell Associate Professor Johannes von Moltke © Jeffrey P. Luppes 2010 To My Parents ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Writing a dissertation is a long, arduous, and often lonely exercise. Fortunately, I have had unbelievable support from many people. First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor and dissertation committee chair, Andrei S. Markovits. Andy has played the largest role in my development as a scholar. In fact, his seminal works on German politics, German history, collective memory, anti-Americanism, and sports influenced me intellectually even before I arrived in Ann Arbor. The opportunity to learn from and work with him was the main reason I wanted to attend the University of Michigan. The decision to come here has paid off immeasurably. Andy has always pushed me to do my best and has been a huge inspiration—both professionally and personally—from the start. His motivational skills and dedication to his students are unmatched. Twice, he gave me the opportunity to assist in the teaching of his very popular undergraduate course on sports and society. He was also always quick to provide recommendation letters and signatures for my many fellowship applications. Most importantly, Andy helped me rethink, re-work, and revise this dissertation at a crucial point. -

MICROCOSM: Portrait of a European City Major Disturbance

In Breslau, the overthrow of the imperial authorities passed off without MICROCOSM: Portrait of a European City major disturbance. On 8 November, a Loyal Appeal for the citizens to uphold by Norman Davies (pp. 326-379) their duties to the Kaiser was distributed in the names of the Lord Mayor, Paul Matting, Archbishop Bertram and others. But it had no great effect. The Commander of the VI Army Corps, General Pfeil, was in no mood for a fight. Breslau before and during the Second World War He released the political prisoners, ordered his men to leave their barracks, 1918-45 and, in the last order of the military administration, gave permission to the Social Democrats to hold a rally in the Jahrhunderthalle. The next afternoon, a The politics of interwar Germany passed through three distinct phases. In group of dissident airmen arrived from their base at Brieg (Brzeg). Their arrival 1918-20, anarchy spread far and wide in the wake of the collapse of the spurred the formation of 'soldiers' councils' (that is, Soviets) in several military German Empire. Between 1919 and 1933, the Weimar Republic re-established units and of a 100-strong Committee of Public Safety by the municipal leaders. stability, then lost it. And from 1933 onwards, Hitler's 'Third Reich' took an The Army Commander was greatly relieved to resign his powers. ever firmer hold. Events in Breslau, as in all German cities, reflected each of The Volksrat, or 'People's Council', was formed on 9 November 1918, from the phases in turn. Social Democrats, union leaders, Liberals and the Catholic Centre Party. -

Gigliotti Et Al. from the Camp to the Road

Geographies.indb 192 2/3/14 10:01 AM 7 From the Camp to the Road Representing the Evacuations from Auschwitz, January 1945 Simone Gigliotti Marc J. Masurovsky and Erik Steiner “They did noT Tell us where we were going – they just said to go – we saw thousands upon thousands of peo- ple – there were all these factories that surrounded Aus- chwitz and all these prisoners joined the march.”1 This commotion, according to Fela Finkelstein, was made all the more menacing by the guards’ threat that “anyone who does not walk, we will shoot, anyone who is weak, we will shoot.”2 From January 17 to 22, 1945, Finkelstein was among an estimated 56,000 Jewish and non-Jewish men, women, and children who were evacuated from forty 193 Geographies.indb 193 2/3/14 10:01 AM camps in the Auschwitz camp complex. The conditions of the evacua- tion journeys, the health of the former camp prisoners, and guards’ abu- sive treatment of them blatantly contradicted the ostensible intention of their preservation and use as forced labor. Most evacuated prisoners walked between fifty and sixty kilometers to interim locations where they awaited rail transport to take them to concentration camps in the German Reich. The slow pace of the columns, moving at an average of no more than three kilometers per hour, made them more vulnerable to violence and Soviet military attacks. The relocation of Auschwitz prisoners had become urgent because January 12 marked the beginning of the Soviet Army’s Vistula-Oder Offensive, eight days ahead of sched- ule.