UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interim Report

INTERIM REPORT ON ELECTION-RELATED VIOLENCE: GENERAL ELECTION 2004 2ND APRIL 2004 Election Day Violations Figure 1 COMPARISON OF ELECTION DAY INCIDENTS: ELECTION DAY 2004 WITH A) POLLING DAY - PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION 1999 B) POLLING DAY - GENERAL ELECTION 2001 General A Election B 2004 General Election 368 incidents 2004 (20%) 368 incidents (27%) Presidential Election 1999 General 973 incidents (73%) Election 2001 1473 (80%) Total number of incidents in both elections 1341 Total number of incidents in both elections 1841 2004 General Election Campaign Source: Centre for Monitoring Election Violence (CMEV) Releases and Reports are signed by the three Co-Convenors, Ms. Sunila Abeysekera, Mr Sunanda Deshapriya and Dr Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu. CMEV Monitors sign a pledge affirming their commitment to independent, non partisan monitoring and are trained before deployment. In addition to local Monitors at all levels, CMEV also deploys International Observers to work with its local Monitors in the INTERIM REPORT field, two weeks to ten days before polling day and on polling day. International Observers are recruited from international civil society organizations and have worked in the human rights and nd ELECTION DAY 2 APRIL 2004 development fields as practitioners, activists and academics. The Centre for Monitoring Election Violence (CMEV) was On Election Day, CMEV deployed 4347 Monitors including 25 formed in 1997 by the Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA), the International Observers. CMEV monitored a total of 6,215 Free Media Movement (FMM) and the Coalition Against Political polling centres or 58.2% of the total of 10,670 polling centres. Violence as an independent non-partisan organization to monitor the incidence of election – related violence. -

The Left and the 1972 Constitution: Marxism and State Power

! 8 The Left and the 1972 Constitution: Marxism and State Power g Kumar David ! ! The drafting of the 1972 Republican Constitution was dominated by the larger than life figure of Dr Colvin R. de Silva (hereafter Colvin), renowned lawyer and brilliant orator, neither of which counts for much for the purposes of this chapter. Colvin was also co-leader with Dr N.M. Perera (hereafter NM) of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), and that is the heart of the matter. Although it was known, rather proudly till recently in the party, as ‘Colvin’s Constitution,’ this terminology is emblematic; no, not just a Colvin phenomenon,1 it was a constitution to which the left parties, that is the LSSP and the Communist Party (CP), were inextricably bound. They cannot separate themselves from its conception, gestation and birth; it was theirs as much as it was the child of Mrs Bandaranaike. Neither can the left wholly brush aside the charge that its brainchild facilitated, to a degree, the enactment of a successor, the 1978 J.R. Jayewardene (hereafter JR) Constitution, which iniquity has yet to be exorcised a quarter of a century later. However, even sans this predecessor but with his 5/6th parliamentary majority, JR who had long been committed to a presidential system would in any case have enacted much the same constitution. But overt politicisation, dismantling of checks and balances, and the alienation of the Tamil minority afforded JR a useful platform to launch out from. The relationship of one constitution to the other is not my subject; my task is the affiliation of the LSSP-CP, their avowed Marxism, and the strategic thinking of the leaders to a constitution that can, at least in hindsight, be euphemistically described as controversial. -

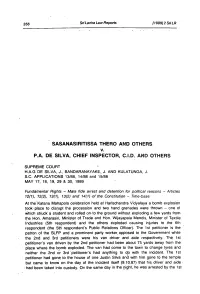

SASANASIRITISSA THERO and OTHERS V. P.A. DE SILVA, CHIEF INSPECTOR, C.I.D

356 Sri Lanka Law Reports (1989) 2 Sri LR SASANASIRITISSA THERO AND OTHERS v. P.A. DE SILVA, CHIEF INSPECTOR, C.I.D. AND OTHERS SUPREME COURT H.A.G DE SILVA, J „ BANDARANAYAKE,. J. AND KULATUNGA, J. S.C. APPLICATIONS 13/88, 14/88 and 15/88 MAY 17, 18, 19, 29 & 30, 1989 Fundamental Rights - Mala tide arrest and detention tor political reasons - Articles 12(1), 12(2), 13(1), 13(2) and 14(1) of the Constitution - Time-base At the Katana Mahapola celebration held at Harischandra Vidyalaya a bomb explosion took place to disrupt the procession and two hand grenades were thrown - one of which struck a student and rolled on to the ground without exploding a few yards from the Hon. Amarasiri, Minister of Trade and Hon. Wijayapala Mendis, Minister of Textile Industries (5th respondent) and the others exploded causing injuries to the 6th respondent (the 5th respondent's Public Relations Officer). The 1st petitioner is the patron of the SLFP and a prominent party worker opposed to the Government while the 2nd. and 3rd petitioners were his van driver and aide respectively. The 1st petitioner’s van driven by the 2nd petitioner had been about 75 yards away from the place where the bomb exploded. The van had come to the town to change tyres and neither the 2nd or 3rd' petitioner's had anything to do with the incident. The 1 st petitioner had gone, to the house of one Justin Silva and with him gone to the temple but came to know on the day of the incident itself (9.10.87) that his driver and aide • had been taken into custody. -

Ruwanwella) Mrs

Lady Members First State Council (1931 - 1935) Mrs. Adline Molamure by-election (Ruwanwella) Mrs. Naysum Saravanamuttu by-election (Colombo North) (Mrs. Molamure was the first woman to be elected to the Legislature) Second State Council (1936 - 1947) Mrs. Naysum Saravanamuttu (Colombo North) First Parliament (House of Representatives) (1947 - 1952) Mrs. Florence Senanayake (Kiriella) Mrs. Kusumasiri Gunawardena by-election (Avissawella) Mrs. Tamara Kumari Illangaratne by-election (Kandy) Second Parliament (House of (1952 - 1956) Representatives) Mrs. Kusumasiri Gunawardena (Avissawella) Mrs. Doreen Wickremasinghe (Akuressa) Third Parliament (House of Representatives) (1956 - 1959) Mrs. Viviene Goonewardene (Colombo North) Mrs. Kusumasiri Gunawardena (Kiriella) Mrs. Vimala Wijewardene (Mirigama) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna by-election (Welimada) Lady Members Fourth Parliament (House of (March - April 1960) Representatives) Mrs. Wimala Kannangara (Galigomuwa) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna (Uva-Paranagama) Mrs. Soma Wickremanayake (Dehiowita) Fifth Parliament (House of Representatives) (July 1960 - 1964) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna (Uva-Paranagama) Mrs. Soma Wickremanayake (Dehiowita) Mrs. Viviene Goonewardene by-election (Borella) Sixth Parliament (House of Representatives) (1965 - 1970) Mrs. Sirima R. D. Bandaranaike (Attanagalla) Mrs. Sivagamie Obeyesekere (Mirigama) Mrs. Wimala Kannangara (Galigomuwa) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna (Uva-Paranagama) Mrs. Leticia Rajapakse by-election (Dodangaslanda) Mrs. Mallika Ratwatte by-election (Balangoda) Seventh Parliament (House of (1970 - 1972) / (1972 - 1977) Representatives) & First National State Assembly Mrs. Kusala Abhayavardhana (Borella) Mrs. Sirima R. D. Bandaranaike (Attanagalla) Mrs. Viviene Goonewardene (Dehiwala - Mt.Lavinia) Lady Members Mrs. Tamara Kumari Ilangaratne (Galagedera) Mrs. Sivagamie Obeyesekere (Mirigama) Mrs. Mallika Ratwatte (Balangoda) Second National State Assembly & First (1977 - 1978) / (1978 - 1989) Parliament of the D.S.R. of Sri Lanka Mrs. Sirima R. D. Bandaranaike (Attanagalla) Miss. -

Discourses of Ethno-Nationalism and Religious Fundamentalism

DISCOURSES OF ETHNO-NATIONALISM AND RELIGIOUS FUNDAMENTALISM SRI LANKAN DISCOURSES OF ETHNO-NATIONALISM AND RELIGIOUS FUNDAMENTALISM By MYRA SIVALOGANATHAN, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Myra Sivaloganathan, June 2017 M.A. Thesis – Myra Sivaloganathan; McMaster University – Religious Studies. McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2017) Hamilton, Ontario (Religious Studies) TITLE: Sri Lankan Discourses of Ethno-Nationalism and Religious Fundamentalism AUTHOR: Myra Sivaloganathan, B.A. (McGill University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Mark Rowe NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 91 ii M.A. Thesis – Myra Sivaloganathan; McMaster University – Religious Studies. Abstract In this thesis, I argue that discourses of victimhood, victory, and xenophobia underpin both Sinhalese and Tamil nationalist and religious fundamentalist movements. Ethnic discourse has allowed citizens to affirm collective ideals in the face of disparate experiences, reclaim power and autonomy in contexts of fundamental instability, but has also deepened ethnic divides in the post-war era. In the first chapter, I argue that mutually exclusive narratives of victimhood lie at the root of ethnic solitudes, and provide barriers to mechanisms of transitional justice and memorialization. The second chapter includes an analysis of the politicization of mythic figures and events from the Rāmāyaṇa and Mahāvaṃsa in nationalist discourses of victory, supremacy, and legacy. Finally, in the third chapter, I explore the Liberation Tiger of Tamil Eelam’s (LTTE) rhetoric and symbolism, and contend that a xenophobic discourse of terrorism has been imposed and transferred from Tamil to Muslim minorities. Ultimately, these discourses prevent Sri Lankans from embracing a multi-ethnic and multi- religious nationality, and hinder efforts at transitional justice. -

Socio-Religious Desegregation in an Immediate Postwar Town Jaffna, Sri Lanka

Carnets de géographes 2 | 2011 Espaces virtuels Socio-religious desegregation in an immediate postwar town Jaffna, Sri Lanka Delon Madavan Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/cdg/2711 DOI: 10.4000/cdg.2711 ISSN: 2107-7266 Publisher UMR 245 - CESSMA Electronic reference Delon Madavan, « Socio-religious desegregation in an immediate postwar town », Carnets de géographes [Online], 2 | 2011, Online since 02 March 2011, connection on 07 May 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/cdg/2711 ; DOI : 10.4000/cdg.2711 La revue Carnets de géographes est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Socio-religious desegregation in an immediate postwar town Jaffna, Sri Lanka Delon MADAVAN PhD candidate and Junior Lecturer in Geography Université Paris-IV Sorbonne Laboratoire Espaces, Nature et Culture (UMR 8185) [email protected] Abstract The cease-fire agreement of 2002 between the Sri Lankan state and the separatist movement of Liberalisation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), was an opportunity to analyze the role of war and then of the cessation of fighting as a potential process of transformation of the segregation at Jaffna in the context of immediate post-war period. Indeed, the armed conflict (1987-2001), with the abolition of the caste system by the LTTE and repeated displacements of people, has been a breakdown for Jaffnese society. The weight of the hierarchical castes system and the one of religious communities, which partially determine the town's prewar population distribution, the choice of spouse, social networks of individuals, values and taboos of society, have been questioned as a result of the conflict. -

Strategic Plan 2017-2020 Election Commission of Sri Lanka 2017-2020

STRATEGIC PLAN STRATEGIC PLAN 2017-2020 ELECTION COMMISSION OF SRI LANKA 2017-2020 Department of Government Printing STRATEGIC PLAN 2017-2020 Election Commission of Sri Lanka Participatory Strategic Plan (PSP) of the Election Commission of Sri Lanka for 2017-2020 “Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives... The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government; this will, shall be expressed in periodic ndenineeetinieniendeend shall be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures.” Article 21, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948 Participatory Strategic Plan (PSP) Election Commission of Sri Lanka 2017-2020 I Foreword By the Chairman and the Members of the Commission Mahinda Deshapriya N. J. Abeysekere, PC Prof. S. Ratnajeevan H. Hoole Chairman Member Member The Soulbury Commission was appointed in 1944 by the British Government in response to strong inteeneeinetefittetetenteineentte population in the governance of the Island, to make recommendations for constitutional reform. The Soulbury Commission recommended, interalia, legislation to provide for the registration of voters and for the conduct of Parliamentary elections, and the Ceylon (Parliamentary Election) Order of the Council, 1946 was enacted on 26th September 1946. The Local Authorities Elections Ordinance was introduced in 1946 to provide for the conduct of elections to Local bodies. The Department of Parliamentary Elections functioned under a Commissioner to register voters and to conduct Parliamentary elections and the Department of Local Government Elections functioned under a Commissioner to conduct Local Government elections. The “Department of Elections” was established on 01st of October 1955 amalgamating the Department of Parliamentary Elections and the Department of Local Government Elections. -

Migration and Morality Amongst Sri Lankan Catholics

UNLIKELY COSMPOLITANS: MIGRATION AND MORALITY AMONGST SRI LANKAN CATHOLICS A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Bernardo Enrique Brown August, 2013 © 2013 Bernardo Enrique Brown ii UNLIKELY COSMOPOLITANS: MIGRATION AND MORALITY AMONGST SRI LANKAN CATHOLICS Bernardo Enrique Brown, Ph.D. Cornell University, 2013 Sri Lankan Catholic families that successfully migrated to Italy encountered multiple challenges upon their return. Although most of these families set off pursuing very specific material objectives through transnational migration, the difficulties generated by return migration forced them to devise new and creative arguments to justify their continued stay away from home. This ethnography traces the migratory trajectories of Catholic families from the area of Negombo and suggests that – due to particular religious, historic and geographic circumstances– the community was able to develop a cosmopolitan attitude towards the foreign that allowed many of its members to imagine themselves as ―better fit‖ for migration than other Sri Lankans. But this cosmopolitanism was not boundless, it was circumscribed by specific ethical values that were constitutive of the identity of this community. For all the cosmopolitan curiosity that inspired people to leave, there was a clear limit to what values and practices could be negotiated without incurring serious moral transgressions. My dissertation traces the way in which these iii transnational families took decisions, constantly navigating between the extremes of a flexible, rootless cosmopolitanism and a rigid definition of identity demarcated by local attachments. Through fieldwork conducted between January and December of 2010 in the predominantly Catholic region of Negombo, I examine the work that transnational migrants did to become moral beings in a time of globalization, individualism and intense consumerism. -

NEWS SRI LANKA Embassy of Sri Lanka, Washington DC

December 2015 NEWS SRI LANKA Embassy of Sri Lanka, Washington DC AMBASSADOR SAMANTHA COMMON VALUES BIND US, POWER VISITS SRI LANKA NOT POWER OR WEALTH “I cannot think of a country in the world today where there has been this much change in this short a period of time.” – PRESIDENT SIRISENA TO THE COMMONWEALTH – Ambassador Samantha Power, Colombo, November 23rd United States Permanent Representative to the UN Ambassa- dor Samantha Power visited Sri Lanka from November 21st to 23rd. Ambassador Samantha Power is the second cabinet Attending the opening ceremony of the Com- knowledge as the Head of the Commonwealth level visitor from the US Administration to travel to Sri Lanka monwealth Heads of Government Meeting in and a great leader for us in the Commonwealth. this year, following Secretary of State John Kerry’s visit in May. Malta on November 27th, President Maithri- During her stay in the country Ambassador Power had a Excellencies, ladies and gentlemen, Sri Lanka pala Sirisena, outgoing Chair-in-Office of the wide range of meetings with the Sri Lankan government, is a founding member of the Commonwealth, Commonwealth made the following statement. civil society and youth. She called on President Maithripala and we are very pleased about its growth over Sirisena, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe and met Your Majesty Queen Elizabeth, Honorable Jo- the past few years. with Minister of Foreign Affairs Mangala Samaraweera and seph Muscat, Prime Minister of Malta, Hon- The influence of the Commonwealth has Leader of the Opposition R. Sampanthan. orable Kamalesh Sharma, Secretary General helped to guide the political and social behav- She travelled to Jaffna where she met with Governor of Commonwealth, Excellencies, Ladies and ior of all our members. -

Ranil Wickremesinghe Sworn in As Prime Minister

September 2015 NEWS SRI LANKA Embassy of Sri Lanka, Washington DC RANIL WICKREMESINGHE VISIT TO SRI LANKA BY SWORN IN AS U.S. ASSISTANT SECRETARIES OF STATE PRIME MINISTER February, this year, we agreed to rebuild our multifaceted bilateral relationship. Several new areas of cooperation were identified during the very successful visit of Secretary Kerry to Colombo in May this year. Our discussions today focused on follow-up on those understandings and on working towards even closer and tangible links. We discussed steps U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for taken by the Government of President South and Central Asian Affairs Nisha Maithripala Sirisena to promote recon- Biswal and U.S. Assistant Secretary of ciliation and to strengthen the rule of State for Democracy, Human Rights law as part of our Government’s overall Following the victory of the United National Front for and Labour Tom Malinowski under- objective of ensuring good governance, Good Governance at the general election on August took a visit to Sri Lanka in August. respect for human rights and strength- 17th, the leader of the United National Party Ranil During the visit they called on Presi- ening our economy. Wickremesinghe was sworn in as the Prime Minister of dent Maithirpala Sirisena, Prime Min- Sri Lanka on August 21. ister Ranil Wickremesinghe and also In keeping with the specific pledge in After Mr. Wickremesinghe took oaths as the new met with Minister of Foreign Affairs President Maithripala Sirisena’s mani- Prime Minister, a Memorandum of Understanding Mangala Samaraweera as well as other festo of January 2015, and now that (MoU) was signed between the Sri Lanka Freedom government leaders. -

Sri Lanka's General Election 2015 Aliff, S

www.ssoar.info Sri Lanka's general election 2015 Aliff, S. M. Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Aliff, S. M. (2016). Sri Lanka's general election 2015. International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences, 68, 7-17. https://doi.org/10.18052/www.scipress.com/ILSHS.68.7 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences Submitted: 2016-01-12 ISSN: 2300-2697, Vol. 68, pp 7-17 Accepted: 2016-02-10 doi:10.18052/www.scipress.com/ILSHS.68.7 Online: 2016-04-07 © 2016 SciPress Ltd., Switzerland Sri Lanka’s General Election 2015 SM.ALIFF Head, Dept. of Political Science, Faculty of Arts & Culture South Eastern University of Sri Lanka, Oluvil Sri Lanka [email protected] Keywords: Parliamentary election of Sri Lanka 2015, Politics of Sri Lanka, Political party, Proportional Representation, Abstract Sri Lanka emerges from this latest election with a hung Parliament in 2015. A coalition called the United National Front for Good Governance (UNFGG) won 106 seats and secured ten out of 22 electoral districts, including Colombo to obtain the largest block of seats at the parliamentary polls, though it couldn’t secure a simple majority in 225-member parliament. It also has the backing of smaller parties that support its agenda of electoral. -

Reforming Sri Lankan Presidentialism: Provenance, Problems and Prospects Volume 2

Reforming Sri Lankan Presidentialism: Provenance, Problems and Prospects Edited by Asanga Welikala Volume 2 18 Failure of Quasi-Gaullist Presidentialism in Sri Lanka Suri Ratnapala Constitutional Choices Sri Lanka’s Constitution combines a presidential system selectively borrowed from the Gaullist Constitution of France with a system of proportional representation in Parliament. The scheme of proportional representation replaced the ‘first past the post’ elections of the independence constitution and of the first republican constitution of 1972. It is strongly favoured by minority parties and several minor parties that owe their very existence to proportional representation. The elective executive presidency, at least initially, enjoyed substantial minority support as the president is directly elected by a national electorate, making it hard for a candidate to win without minority support. (Sri Lanka’s ethnic minorities constitute about 25 per cent of the population.) However, there is a growing national consensus that the quasi-Gaullist experiment has failed. All major political parties have called for its replacement while in opposition although in government, they are invariably seduced to silence by the fruits of office. Assuming that there is political will and ability to change the system, what alternative model should the nation embrace? Constitutions of nations in the modern era tend fall into four categories. 1.! Various forms of authoritarian government. These include absolute monarchies (emirates and sultanates of the Islamic world), personal dictatorships, oligarchies, theocracies (Iran) and single party rule (remaining real or nominal communist states). 2.! Parliamentary government based on the Westminster system with a largely ceremonial constitutional monarch or president. Most Western European countries, India, Japan, Israel and many former British colonies have this model with local variations.