Sirimavo Bandaranaike Ranasinghe Premadasa And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“ the Ceylon Government Gazette” January to June, 1956

[Supphmtnt to Ike “ Ceylon Government Gazette ” o f October 12,1956] INDEX TO /'S'* “ THE CEYLON GOVERNMENT GAZETTE” JANUARY TO JUNE, 1956 No. 10,875 t o No. 10,946 PART I: SECTION (I) — GENERAL PAGES PAGES PAGES PAG8S Posts and Telecommunications vil ii Honours by the Queen Vl-Vlj Accounts of the Government Customs Pi ice Orders v!l of Ceylon » * Education, Department oT in Honours b ; the Queen (Birthday) — Proclamations by the Gover-Genoral vii Appointments, &c. i-u Indian Labour vii Electrical Undertakings, Depart Publications 4 vil Appointments, &o , of Registrars u ment of Government —* Industries, Department of VI! Public Works Department .. viil Buddhist Temporalities — Excise Department — vil Irrigation Department Railway, Ceylon Government vih Central Bank of Ceylon » in VII Forest Department Joint Stock Companies Registration vih Ceylon Army — General Treasury — Miscellaneous VII Rural Development and Cottage Ceylon Medical Council . — Government Notifications . hl-vi Notices to Mariners Vil Industries, Dept of vil! Ceylon Savings Bank u Survey Department — Health, Department of — Notices under the Excise Cottage Industries, Dept of ~~ Ordinance Vil University of Ceylon . vm Accounts of the Government of Boudewyn, Ipz H G . 78 De Silva. S i t , 207 Goonewardena, H C 724 Ceylon Buidei, V D , 639, &40 De Silva, S W A , 383, 1198 Goonewardene, 8 B , 236 Busby, F G 0 , 642 De Silva W A , 1014 Gratiaen, E F N , 721 Statement of Assets and Liabilities, De Soysa, M A , 568 Grero P J , 383 Devapura, L P , 383 Greve, Temp Major M M . 1185 &c, of the Government of Ceylon Devendra, N , 1104 1164, 1196 as at December 31, 1955, 1071 Caldeia, Ipr A It F, /8 Gulasekharsm, C C J 709 De Zoysa E B K , 593 Gunadasa, H W , 1198 Canoga Retna, J M K , 236 De Zoysa, L ii 383 Canagasabai, V , 1164 Gunaratna, A , 383 Appointments, 4c De Zoysa, M P 721, 1163 Gunaratnam, 8 C 383 Canon, T P C . -

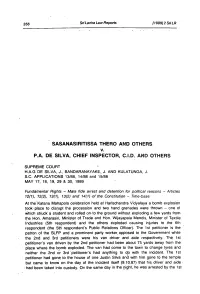

SASANASIRITISSA THERO and OTHERS V. P.A. DE SILVA, CHIEF INSPECTOR, C.I.D

356 Sri Lanka Law Reports (1989) 2 Sri LR SASANASIRITISSA THERO AND OTHERS v. P.A. DE SILVA, CHIEF INSPECTOR, C.I.D. AND OTHERS SUPREME COURT H.A.G DE SILVA, J „ BANDARANAYAKE,. J. AND KULATUNGA, J. S.C. APPLICATIONS 13/88, 14/88 and 15/88 MAY 17, 18, 19, 29 & 30, 1989 Fundamental Rights - Mala tide arrest and detention tor political reasons - Articles 12(1), 12(2), 13(1), 13(2) and 14(1) of the Constitution - Time-base At the Katana Mahapola celebration held at Harischandra Vidyalaya a bomb explosion took place to disrupt the procession and two hand grenades were thrown - one of which struck a student and rolled on to the ground without exploding a few yards from the Hon. Amarasiri, Minister of Trade and Hon. Wijayapala Mendis, Minister of Textile Industries (5th respondent) and the others exploded causing injuries to the 6th respondent (the 5th respondent's Public Relations Officer). The 1st petitioner is the patron of the SLFP and a prominent party worker opposed to the Government while the 2nd. and 3rd petitioners were his van driver and aide respectively. The 1st petitioner’s van driven by the 2nd petitioner had been about 75 yards away from the place where the bomb exploded. The van had come to the town to change tyres and neither the 2nd or 3rd' petitioner's had anything to do with the incident. The 1 st petitioner had gone, to the house of one Justin Silva and with him gone to the temple but came to know on the day of the incident itself (9.10.87) that his driver and aide • had been taken into custody. -

Migration and Morality Amongst Sri Lankan Catholics

UNLIKELY COSMPOLITANS: MIGRATION AND MORALITY AMONGST SRI LANKAN CATHOLICS A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Bernardo Enrique Brown August, 2013 © 2013 Bernardo Enrique Brown ii UNLIKELY COSMOPOLITANS: MIGRATION AND MORALITY AMONGST SRI LANKAN CATHOLICS Bernardo Enrique Brown, Ph.D. Cornell University, 2013 Sri Lankan Catholic families that successfully migrated to Italy encountered multiple challenges upon their return. Although most of these families set off pursuing very specific material objectives through transnational migration, the difficulties generated by return migration forced them to devise new and creative arguments to justify their continued stay away from home. This ethnography traces the migratory trajectories of Catholic families from the area of Negombo and suggests that – due to particular religious, historic and geographic circumstances– the community was able to develop a cosmopolitan attitude towards the foreign that allowed many of its members to imagine themselves as ―better fit‖ for migration than other Sri Lankans. But this cosmopolitanism was not boundless, it was circumscribed by specific ethical values that were constitutive of the identity of this community. For all the cosmopolitan curiosity that inspired people to leave, there was a clear limit to what values and practices could be negotiated without incurring serious moral transgressions. My dissertation traces the way in which these iii transnational families took decisions, constantly navigating between the extremes of a flexible, rootless cosmopolitanism and a rigid definition of identity demarcated by local attachments. Through fieldwork conducted between January and December of 2010 in the predominantly Catholic region of Negombo, I examine the work that transnational migrants did to become moral beings in a time of globalization, individualism and intense consumerism. -

Update UNHCR/CDR Background Paper on Sri Lanka

NATIONS UNIES UNITED NATIONS HAUT COMMISSARIAT HIGH COMMISSIONER POUR LES REFUGIES FOR REFUGEES BACKGROUND PAPER ON REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS FROM Sri Lanka UNHCR CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH GENEVA, JUNE 2001 THIS INFORMATION PAPER WAS PREPARED IN THE COUNTRY RESEARCH AND ANALYSIS UNIT OF UNHCR’S CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH ON THE BASIS OF PUBLICLY AVAILABLE INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND COMMENT, IN COLLABORATION WITH THE UNHCR STATISTICAL UNIT. ALL SOURCES ARE CITED. THIS PAPER IS NOT, AND DOES NOT, PURPORT TO BE, FULLY EXHAUSTIVE WITH REGARD TO CONDITIONS IN THE COUNTRY SURVEYED, OR CONCLUSIVE AS TO THE MERITS OF ANY PARTICULAR CLAIM TO REFUGEE STATUS OR ASYLUM. ISSN 1020-8410 Table of Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS.............................................................................................................................. 3 1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................... 4 2 MAJOR POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS IN SRI LANKA SINCE MARCH 1999................ 7 3 LEGAL CONTEXT...................................................................................................................... 17 3.1 International Legal Context ................................................................................................. 17 3.2 National Legal Context........................................................................................................ 19 4 REVIEW OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION............................................................... -

Chapter 5 ECONOMIC and SOCIAL OVERHEADS

Chapter 5 ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL OVERHEADS 5.1 Overview The quality and coverage of the available physical and social such regulatory functions, initially covering the electricity, infrastructure supported by an efficient and effective regulatory water and petroleum sectors. system constitute the crucial factors for creating a conducive In 2003, further progress in reforms was evident investment climate in a country. However, as common to many particularly in the petroleum, electricity, and rail transportation developing countries, Sri Lanka is in need of substantial and telecommunication sectors. The domestic petroleum improvement in infrastructure facilities. The development of market was opened for competition thus ending the monopoly infrastructure responds positivery to liberalisation, derigulation in petroleum importation and distribution. Lanka Indian oil In some sectors and private sector participation as has been corporation (LIoc) commenced retailing of petroleum experienced in other countries. Lanka sri is not an exception products from March 2003. A third player in importing and to this general rule. The need for creating a conducive distributing petroleum products is expected to commence environment for infrastructure development in sri Lanka has operations in 2004.In the petroleum sector, a common user been identified, but a vigorous pursuit of this goal has not been facility company, ceylon Petroleum Storage Terminals Ltd followed adequately or continuously. (CPSTL) to manage key petroleum infrastructure such as oil Many enterprises supplying infrastructure services are terminals, storage facilities and pipelines, was set up. The owned by or remain monopolies of the government. Services formula based petroleum pricing policy was ough rendered by many of these are below the expected service there were some interventions, particular Iraq norms, while being unviable and therefore dependent on war, when international petroleum prices w high government assistance, although they could be profitably run. -

Transitional Justice for Women Ex-Combatants in Sri Lanka

Transitional Justice for Women Ex-Combatants in Sri Lanka Nirekha De Silva Transitional Justice for Women Ex-Combatants in Sri Lanka Copyright© WISCOMP Foundation for Universal Responsibility Of His Holiness The Dalai Lama, New Delhi, India, 2006. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by WISCOMP Foundation for Universal Responsibility Of His Holiness The Dalai Lama Core 4A, UGF, India Habitat Centre Lodhi Road, New Delhi 110 003, India This initiative was made possible by a grant from the Ford Foundation. The views expressed are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect those of WISCOMP or the Foundation for Universal Responsibility of HH The Dalai Lama, nor are they endorsed by them. 2 Contents Acknowledgements 5 Preface 7 Introduction 9 Methodology 11 List of Abbreviations 13 Civil War in Sri Lanka 14 Army Women 20 LTTE Women 34 Peace and the process of Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration 45 Human Needs and Human Rights in Reintegration 55 Psychological Barriers in Reintegration 68 Social Adjustment to Civil Life 81 Available Mechanisms 87 Recommendations 96 Directory of Available Resources 100 • Counselling Centres 100 • Foreign Recruitment 102 • Local Recruitment 132 • Vocational Training 133 • Financial Resources 160 • Non-Government Organizations (NGO’s) 163 Bibliography 199 List of People Interviewed 204 3 4 Acknowledgements I am grateful to Dr. Meenakshi Gopinath and Sumona DasGupta of Women in Security, Conflict Management and Peace (WISCOMP), India, for offering the Scholar for Peace Fellowship in 2005. -

Chapter Iv Sri Lanka and the International System

1 CHAPTER IV SRI LANKA AND THE INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM : THE UNP GOVERNMENTS In the system of sovereign states, individual states interact with other states and international organizations to protect and promote their national interests. As the issues and scope of the interests of different classes of states vary, so do the character and patterns of their interactions to preserve and promote them. Unlike the super powers whose national interests encompass the entire sovereign states system, the small states have a relatively limited range of interests as well as a relatively limited sphere of foreign policy activities. As a small state, Sri Lanka has a relatively small agenda of interests in the international arena and the sphere of its foreign policy activities is quite restricted in comparison to those of the super powers, or regional powers. The sphere of its foreign policy activities can be analytically separated into two levels : those in the South Asian regional system and those in the larger international system.1 In the South Asian regional system Sri Lanka has to treat India with due caution because of the existence of wide difference in their respective capabilities, yet try to maintain its sovereignty, freedom and integrity. In the international system apart from mitigating the pressures and pulls emanating from the international power structure, Sri Lanka has to promote its national interests to ensure its security, stability and status. Interactions of Sri Lanka to realize its national interests to a great extent depended upon the perceptions and world views of its ruling elites, which in its case are its heads of governments and their close associates.2 Although the foreign policy makers have enjoyed considerable freedom in taking initiatives in the making and conduct of foreign policy, their 2 freedom is subject to the constraints imposed by the domestic and international determinants of its foreign policy. -

Sri Lanka Assessment

SRI LANKA COUNTRY ASSESSMENT October 2002 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Sri Lanka October 2002 CONTENTS 1. Scope of Document 1.1 - 1.4 2. Geography 2.1 - 2.4 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.2 4. History 4.1 - 4.79 - Independence to 1994 4.1 - 4.10 - 1994 to the present 4.11 - 4.50 - The Peace Process January 2000 - October 4.51 - 4.79 2002 5. State Structures 5.1 - 5.34 The Constitution 5.1 - 5.2 - Citizenship and Nationality 5.3 - 5.4 Political System 5.5. - 5.7 Judiciary 5.8 - 5.10 Legal Rights/Detention 5.11 - 5.21 - Death penalty 5.22 - 5.23 Internal Security 5.24 - 5.25 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.26 Military Service 5.27 - 5.28 Medical Services 5.29 - 5.33 Educational System 5.34 6. Human Rights 6.1 - 6.168 6.A Human Rights Issues 6.1 - 6.51 Overview 6.1 - 6.4 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.5 - 6.8 - Treatment of journalists 6.9 - 6.11 Freedom of Religion - Introduction 6.12 - Buddhists 6.13 - Hindus 6.14 - Muslims 6.15 - 6.18 - Christians 6.19 - Baha'is 6.20 Freedom of Assembly & Association 6.21 - Political Activists 6.22 - 6.26 Employment Rights 6.27 - 6.32 People Trafficking 6.33 - 6.35 Freedom of Movement 6.36 - 6.43 - Immigrants and Emigrants Act 6.44 - 6.51 6.B Human Rights - Specific Groups 6.52 - 6.151 Ethnic Groups - Tamils and general Human Rights Issues 6.52 - 6.126 - Up-country Tamils 6.127 - 6.130 - Indigenous People 6.131 Women 6.132 - 6.139 Children 6.140 - 6.145 - Child Care Arrangements 6.146 - 6.150 Homosexuals 6.151 6.C Human Rights - Other Issues -

A Study of Violent Tamil Insurrection in Sri Lanka, 1972-1987

SECESSIONIST GUERRILLAS: A STUDY OF VIOLENT TAMIL INSURRECTION IN SRI LANKA, 1972-1987 by SANTHANAM RAVINDRAN B.A., University Of Peradeniya, 1981 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Political Science We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA February 1988 @ Santhanam Ravindran, 1988 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Political Science The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date February 29, 1988 DE-6G/81) ABSTRACT In Sri Lanka, the Tamils' demand for a federal state has turned within a quarter of a century into a demand for the independent state of Eelam. Forces of secession set in motion by emerging Sinhala-Buddhist chauvinism and the resultant Tamil nationalism gathered momentum during the 1970s and 1980s which threatened the political integration of the island. Today Indian intervention has temporarily arrested the process of disintegration. But post-October 1987 developments illustrate that the secessionist war is far from over and secession still remains a real possibility. -

An Account of Happenings in 2017

22 SUNDAY OBSERVER DECEMBER 31, 2017 SUNDAY OBSERVER DECEMBER 31, 2017 23 Flashback 2017 Flashback 2017 Health Minister Rajitha Senaratne bans of pa- The newly appointed Secretary to the Sri Lanka signs US$1.1 billion deal to lease the 01 tients in Government hospitals with blood test- The European Commission proposed GSP+ con- President Maithripala Sirisena appoints 04 President, Defence Secretary, Command- 29 Southern Hambantota Port to China. ing facilities from taking blood tests from private sec- 12 cessions to Sri Lanka in exchange for the govern- 28 members to Special Presidential Com- er of the Army and the Eastern Province Gover- tor. ment’s commitment to ratify 27 international conven- mission on CB Bond issue. Supreme Court Judge nor sworn in before President Maithripala Siris- tions on human rights, labour conditions, protection of Kankanithanthri T. Chitrasiri, Supreme Court ena The government announces free health insur- the environment and good governance. Judge Prasanna Sujeewa Jayawardena, and re- The Colombo High Court impose death 01 - Sri Lanka – China Logistics and Industrial Zone tired Deputy Auditor General Vellupillai Kan- 06 sentence on Anthony Ramson George, num for every student. 08 (SLCLIZ) in Hambantota inaugurated dasamy appointed. convicted for the murder of journalist Melicia Gunas- 01 President Maithripala Sirisena launches the 08 Inauguration ceremony of the Third Year of 30 First-ever President’s Truncheon and the ekara in 2014. Government’s vision for ‘Sustainable Era’ and the Sustainable Era national initiative held at Regimental Truncheon awarded to Sri JULY AUGUST SEPTEMBER OCTOBER NOVEMBER DECEMBER presented the framework program of Sri Lanka, set to BMICH Lanka Sinha Regiment (SLSR), at the Sinha Regi- outline the Government’s strategies for achieving 2030 mental Headquarters in Ambepussa UN Sustainable Development Goals. -

Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalist Ideology: Implications for Politics and Conflict Resolution in Sri Lanka

Policy Studies 40 Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalist Ideology: Implications for Politics and Conflict Resolution in Sri Lanka Neil DeVotta East-West Center Washington East-West Center The East-West Center is an internationally recognized education and research organization established by the U.S. Congress in 1960 to strengthen understanding and relations between the United States and the countries of the Asia Pacific. Through its programs of cooperative study, training, seminars, and research, the Center works to promote a stable, peaceful, and prosperous Asia Pacific community in which the United States is a leading and valued partner. Funding for the Center comes from the U.S. government, private foundations, individuals, cor- porations, and a number of Asia Pacific governments. East-West Center Washington Established on September 1, 2001, the primary function of the East- West Center Washington is to further the East-West Center mission and the institutional objective of building a peaceful and prosperous Asia Pacific community through substantive programming activities focused on the themes of conflict reduction, political change in the direction of open, accountable, and participatory politics, and American under- standing of and engagement in Asia Pacific affairs. Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalist Ideology: Implications for Politics and Conflict Resolution in Sri Lanka Policy Studies 40 ___________ Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalist Ideology: Implications for Politics and Conflict Resolution in Sri Lanka ___________________________ Neil DeVotta Copyright © 2007 by the East-West Center Washington Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalist Ideology: Implications for Politics and Conflict Resolution in Sri Lanka By Neil DeVotta ISBN: 978-1-932728-65-1 (online version) ISSN: 1547-1330 (online version) Online at: www.eastwestcenterwashington.org/publications East-West Center Washington 1819 L Street, NW, Suite 200 Washington, D.C. -

IN PURSUIT of HEGEMONY: Politics and State Building in Sri Lanka

IN PURSUIT OF HEGEMONY: Politics and State Building in Sri Lanka Shyamika Jayasundara-Smits This dissertation is part of the Research Programme of Ceres, Research School for Resource Studies for Development. © Shyamika Jayasundara-Smits 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the author. Printed in The Netherlands. ISBN 978-94-91478-12-3 IN PURSUIT OF HEGEMONY: Politics and State Building in Sri Lanka OP ZOEK NAAR HEGEMONIE: Politiek en staatsvorming in Sri Lanka Thesis to obtain the degree of Doctor from the Erasmus University Rotterdam by command of the Rector Magnificus Professor dr H.G. Schmidt and in accordance with the decision of the Doctorate Board The public defence shall be held on 23 May 2013 at 16.00 hrs by Seneviratne Mudiyanselage Shyamika Jayasundara-Smits born in Colombo, Sri Lanka Doctoral Committee Promotor Prof.dr. M.A.R.M. Salih Other Members Prof.dr. N.K. Wickramasinghe, Leiden University Prof.dr. S.M. Murshed Associate professor dr. D. Zarkov Co-promotor Dr. D. Dunham Contents List of Tables, Diagrams and Appendices viii Acronyms x Acknowledgements xii Abstract xv Samenvatting xvii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Literature Review 1 1.1.1 Scholarship on Sri Lanka 4 1.2 The Setting and Justification 5 1.2.1 A Statement of the Problem 10 1.3 Research Questions 13 1.4 Central Thesis Statement 14 1.5 Theories and concepts 14 1.5.1