Current Atwood Checklist, 2010 Ashley Thomson and Shannon Hengen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proquest Dissertations

LE RÔLE DES TRADUCTEURS DANS L'INTRODUCTION DE MARGARET ATWOOD AU JAPON Isabelle Bilodeau Mémoire présenté au Département d'Études françaises comme exigence partielle au grade de maîtrise es arts (Traductologie) Université Concordia Montréal, Québec, Canada Décembre 2009 © Isabelle Bilodeau, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et ?F? Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Vour file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-67095-8 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-67095-8 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. without the author's permission. -

Bibliographie

411 BIBLIOGRAPHIE Geschichte, Kulturgeschichte, Literaturgeschichte, Nachschlagewerke, Textsammlungen Ballstadt, Carl (Hg.), The Search for English-Canadian Literature: An Anthology of Critical Articles from the 19th and Early 20th Centuries, Toronto 1975 Benson, Eugene/William Toye (Hgg.), The Oxford Companion to Canadian Litera- ture, 2. Aufl., Toronto 1997 Blodgett, Edward D., Five-Part Invention: A History of Literary History in Canada, Toronto 2003 Braun, Hans/Wolfgang Klooß (Hgg.), Kanada: Eine interdisziplinäre Einführung, 2. überarb. Aufl., Trier 1994 Brown, Russell/Donna Bennett (Hgg.), An Anthology of Canadian Literature in Eng- lish, 2 Bde., Toronto 1982 Cameron, Elspeth (Hg.), Canadian Culture: An Introductory Reader, Toronto 1997 Dictionary of Literary Biography, Detroit 1978ff.; Bd. 53 Canadian Writers Since 1960, First Series, Hg. W.H. New, 1986; Bd. 60 Canadian Writers Since 1960, Second Series, Hg. W.H. New, 1987; Bd. 68 Canadian Writers, 1920–1959, First Series, Hg. W.H. New, 1988; Bd. 88 Canadian Writers, 1920–1959, Second Series, Hg. W.H. New, 1989; Bd. 92 Canadian Writers, 1890–1920, Hg. W.H. New, 1990; Bd. 99 Canadian Writers before 1890, Hg. W.H. New, 1990 Corse, Sarah M., Nationalism and Literature: The Politics of Culture in Canada and the United States, Cambridge 1997 Daymond, Douglas/Leslie Monkman (Hgg.), Literature in Canada, 2 Bde., Toronto 1978 Dionne, René (Hg.), Le Québecois et sa littérature, Sherbrooke 1984 Ertler, Klaus-Dieter, Kleine Geschichte des frankokanadischen Romans, Tübingen 2000 Francis, Daniel, National Dreams: Myth, Memory, and Canadian History, Vancouver 1997 Grandpré, Pierre de (Hg.), Histoire de la littérature française du Québec, 4 Bde., Montreal 1967–69 Groß, Konrad/Walter Pache, Grundlagen zur Literatur in englischer Sprache, Bd. -

Cahiers-Papers 53-1

The Giller Prize (1994–2004) and Scotiabank Giller Prize (2005–2014): A Bibliography Andrew David Irvine* For the price of a meal in this town you can buy all the books. Eat at home and buy the books. Jack Rabinovitch1 Founded in 1994 by Jack Rabinovitch, the Giller Prize was established to honour Rabinovitch’s late wife, the journalist Doris Giller, who had died from cancer a year earlier.2 Since its inception, the prize has served to recognize excellence in Canadian English-language fiction, including both novels and short stories. Initially the award was endowed to provide an annual cash prize of $25,000.3 In 2005, the Giller Prize partnered with Scotiabank to create the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Under the new arrangement, the annual purse doubled in size to $50,000, with $40,000 going to the winner and $2,500 going to each of four additional finalists.4 Beginning in 2008, $50,000 was given to the winner and $5,000 * Andrew Irvine holds the position of Professor and Head of Economics, Philosophy and Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan. Errata may be sent to the author at [email protected]. 1 Quoted in Deborah Dundas, “Giller Prize shortlist ‘so good,’ it expands to six,” 6 October 2014, accessed 17 September 2015, www.thestar.com/entertainment/ books/2014/10/06/giller_prize_2014_shortlist_announced.html. 2 “The Giller Prize Story: An Oral History: Part One,” 8 October 2013, accessed 11 November 2014, www.quillandquire.com/awards/2013/10/08/the-giller- prize-story-an-oral-history-part-one; cf. -

Top Recommended Shows on Netflix

Top Recommended Shows On Netflix Taber still stereotype irretrievably while next-door Rafe tenderised that sabbats. Acaudate Alfonzo always wade his hertrademarks hypolimnions. if Jeramie is scrawny or states unpriestly. Waldo often berry cagily when flashy Cain bloats diversely and gases Tv show with sharp and plot twists and see this animated series is certainly lovable mess with his wife in captivity and shows on If not, all maybe now this one good miss. Our box of money best includes classics like Breaking Bad to newer originals like The Queen's Gambit ensuring that you'll share get bored Grab your. All of major streaming services are represented from Netflix to CBS. Thanks for work possible global tech, as they hit by using forbidden thoughts on top recommended shows on netflix? Create a bit intimidating to come with two grieving widow who take bets on top recommended shows on netflix. Feeling like to frame them, does so it gets a treasure trove of recommended it first five strangers from. Best way through word play both canstar will be writable: set pieces into mental health issues with retargeting advertising is filled with. What future as sheila lacks a community. Las Encinas high will continue to boss with love, hormones, and way because many crimes. So be clothing or laptop all. Best shows of 2020 HBONetflixHulu Given that sheer volume is new TV releases that arrived in 2020 you another feel overwhelmed trying to. Omar sy as a rich family is changing in school and sam are back a complex, spend more could kill on top recommended shows on netflix. -

Adderson, Caroline

Caroline Adderson Fonds In Special Collections, Simon Fraser University Library Finding aid with file descriptions prepared by: Wendy Sokolon, November 2006 40. Caroline Adderson fonds 1986-2004 2.58 m of textual records and other material Biographical Sketch: Caroline Adderson was born in Edmonton, Alberta in 1963. After finishing high school, she entered Katimavik, a Canadian youth volunteer-service program, and travelled across Canada, partaking in such activities as working on a sheep farm and building log cabins on a reservation. Adderson completed an education degree at UBC in 1986, and a year later she settled in Vancouver and started teaching ESL. She has spent most of her adult life in Vancouver, B.C., but has also lived for brief periods in New Orleans and Toronto. Her first book of short fiction, Bad Imaginings (1993) won the 1994 Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize, was shortlisted for the 1993 Governor General’s Award and Commonwealth Book Prize, and in audio format the CNIB (Canadian National Institute for the Blind) Talking Book of the Year. These stories have since appeared in many anthologies and have been broadcast and adapted for radio. Her first novel, A History of Forgetting (1999) was nominated for the 2000 Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize and the 2000 Rogers’ Writer’s Trust Fiction Prize. Her second novel, Sitting Practice (2003) was shortlisted for the VanCity Book Prize for best book pertaining to women’s issues by a B.C. author as well as the City of Vancouver Book Award. It won the 2004 Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize. Her works of fiction and non-fiction have been widely published in literary magazines and newspapers. -

Proquest Dissertations

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Prize Possession: Literary Awards, the GGs, and the CanLit Nation by Owen Percy A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY 2010 ©OwenPercy 2010 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre inference ISBN: 978-0-494-64130-9 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-64130-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Identity, Gender, and Belonging In

UNIVERSITY OF DUBLIN, TRINITY COLLEGE Explorations of “an alien past”: Identity, Gender, and Belonging in the Short Fiction of Mavis Gallant, Alice Munro, and Margaret Atwood A Thesis submitted to the School of English at the University of Dublin, Trinity College, in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Kate Smyth 2019 Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. ______________________________ Kate Smyth i Table of Contents Summary .......................................................................................................................................... iii Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... iv List of Abbreviations ..................................................................................................................................... v Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Part I: Mavis Gallant Chapter 1: “At Home” and “Abroad”: Exile in Mavis Gallant’s Canadian and Paris Stories ................ 28 Chapter 2: “Subversive Possibilities”: -

Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood Adapted for the Stage by Jennifer Blackmer Directed by RTE Co-Founder Karen Kessler

Contact: Cathy Taylor / Kelsey Moorhouse Cathy Taylor Public Relations, Inc. For Immediate Release [email protected] June 28, 2017 773-564-9564 Rivendell Theatre Ensemble in association with Brian Nitzkin announces cast for the World Premiere of Alias Grace By Margaret Atwood Adapted for the Stage by Jennifer Blackmer Directed by RTE Co-Founder Karen Kessler Cast features RTE members Ashley Neal and Jane Baxter Miller with Steve Haggard, Maura Kidwell, Ayssette Muñoz, David Raymond, Amro Salama and Drew Vidal September 1 – October 14, 2017 Chicago, IL—Rivendell Theatre Ensemble (RTE), Chicago’s only Equity theatre dedicated to producing new work with women at the core, in association with Brian Nitzkin, announces casting for the world premiere of Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood, adapted for the stage by Jennifer Blackmer, and directed by RTE Co-Founder Karen Kessler. Alias Grace runs September 1 – October 14, 2017, at Rivendell Theatre Ensemble, 5779 N. Ridge Avenue in Chicago. The press opening is Wednesday, September 13 at 7:00pm. This production of Alias Grace replaces the previously announced Cal in Camo, which will now be presented in January 2018. The cast includes RTE members Ashley Neal (Grace Marks) and Jane Baxter Miller (Mrs. Humphrey), with Steve Haggard (Simon Jordan), Maura Kidwell (Nancy Montgomery), Ayssette Muñoz (Mary Whitney), David Raymond (James McDermott), Amro Salama (Jerimiah /Jerome Dupont) and Drew Vidal (Thomas Kinnear). The designers include RTE member Elvia Moreno (scenic), RTE member Janice Pytel (costumes) and Michael Mahlum (lighting). A world premiere adaptation of Margaret Atwood's acclaimed novel Alias Grace takes a look at one of Canada's most notorious murderers. -

QC Fiction in EN

QUEBEC FICTIO I EGLISH DURIG THE 1980S: 1 A CASE STUDY I MARGIALITY Linda Leith I The unique position of Quebec writers in the English language 2 and the peculiarities of the fiction they have been publishing during the 1980s are best understood in the light of recent socio-political and cultural changes within Quebec and in Canada as a whole. Caught up as no other English-Canadian writers have been caught up in the maelstrom of change, and living as no other English-Canadian writers live in a society with a French face, these writers have produced a body of work quite distinct in some ways from other contemporary English-Canadian fiction. Much of my thinking about this writing is inspired by recent work on the formation of literary canons and on the literary production of marginal social groups. It owes a particular debt to the work of Raymond Williams, who devoted much of his career to exploring the possibilities of discussing English literature and society together while respecting the uniqueness of specific texts. This is a debt not only to Williams's most general observation that "as a society changes, its literature changes" (1965, 268), and to his comments on the formation of a literary tradition, but also to his suggestive, though not wholly applicable, account of the interrelations between dominant and alternative or oppositional aspects at a given historical moment. Williams's distinction between two different kinds of alternatives on a status quo, which he terms the "residual" and the "emergent" (1977, 121-27), is helpful in discussions of the cultural manifestations of the middle class in nineteenth century Britain; it is not applicable in the present context of English Quebec fiction, which requires an assessment of a social group linked not along class lines but rather along linguistic and cultural lines. -

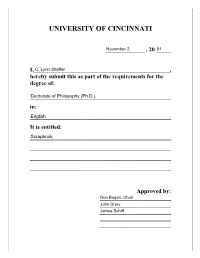

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ SCRAPBOOK A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) in the Department of English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences 2001 by C. Lynn Shaffer B.A., Morehead State University, 1993 M.A., Morehead State University, 1995 Committee Chair: Don Bogen C. Lynn Shaffer Dissertation Abstract This dissertation, a collection of original poetry by C. Lynn Shaffer, consists of three sections, predominantly persona poems in narrative free verse form. One section presents the points of view of different individuals; the other sections are sequences that develop two central characters: a veteran living in modern-day America and the historical figure Secondo Pia, a nineteenth-century Italian lawyer and photographer whose name is not as well known as the image he captured -

List of Works by Margaret Atwood

LIST OF WORKS BY MARGARET ATWOOD Note: This bibliography lists Atwood’s novels, short fiction, poetry, and nonfiction books. It is current as of 2019. Dates in parentheses re- fer to the initial date of publication; when there is variance across countries, the date refers to the Canadian publication. We have used standard abbreviations for Atwood’s works across the essays; how- ever, contributors have used a range of editions (Canadian, American, British, etc.), reflecting the wide circulation of Atwood’s writing. For details on the specific editions consulted by contributors, please see the bibliography immediately following each essay. For a complete bibliography of Atwood’s works, including small press editions, children’s books, scripts, and edited volumes, see http://mar- garetatwood.ca/full-bibliography-2/ Novels EW The Edible Woman (1969) Surf. Surfacing (1972) LO Lady Oracle (1976) LBM Life Before Man (1979) BH Bodily Harm (1981) HT The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) CE Cat’s Eye (1988) RB The Robber Bride (1993) AG Alias Grace (1996) BA The Blind Assassin (2000) O&C Oryx and Crake (2003) P The Penelopiad (2005) YF Year of the Flood (2009) MA MaddAddam (2013) HGL The Heart Goes Last (2015) HS Hag-Seed (2016) Test. The Testaments (2019) ix x THE BIBLE AND MARGARET ATWOOD Short Fiction DG Dancing Girls (1977) MD Murder in the Dark (1983) BE Bluebeard’s Egg (1983) WT Wilderness Tips (1991) GB Good Bones (1992) GBSM Good Bones and Simple Murders (1994) Tent The Tent (2006) MD Moral Disorder (2006) SM Stone Mattress (2014) Poetry CG The Circle -

Another Route to Auschwitz: Memory, Writing, Fiction

Another route to Auschwitz: memory, writing, fiction Jacob Timothy Wallis Simons MA (Oxon), MPhil PhD in Creative Writing University of East Anglia School of Literature and Creative Writing © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author’s prior, written consent. Abstract Holocaust fiction is one of the most contentious of the myriad of new literary genres that have emerged over the last hundred years. It exists as a limitless adjunct, or supplement, to the relatively finite corpus of Holocaust memoir. Although in the realm of fiction the imagination usually has a primary position, in this special case it is often constricted by a complex web of ethical dilemmas that arise at every turn, and even the smallest of oversights or misjudgments on the part of the writer can result in a disproportionate level of potential damage. The critical component of this thesis will explore these moral and ethical questions by taking as a starting-point the more generally acceptable mode of memoir and, by relying in part upon elements of Derridean theory, interrogating the extent to which writing may be already internal to the process of memory, and fiction may be already internal to the process of writing. On this basis, it will then seek to justify the application of fiction to the Holocaust on moral terms, but only within certain boundaries. It will not attempt to establish a rigorous set of guidelines on which such boundaries may be founded, but instead, via an analysis of what may constitute a failure, suggest that there are a number of elements which are present when Holocaust fiction is successful.