Epistolary Encounters: Diary and Letter Pastiche in Neo-Victorian Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cutting Patterns in DW Griffith's Biographs

Cutting patterns in D.W. Griffith’s Biographs: An experimental statistical study Mike Baxter, 16 Lady Bay Road, West Bridgford, Nottingham, NG2 5BJ, U.K. (e-mail: [email protected]) 1 Introduction A number of recent studies have examined statistical methods for investigating cutting patterns within films, for the purposes of comparing patterns across films and/or for summarising ‘average’ patterns in a body of films. The present paper investigates how different ideas that have been proposed might be combined to identify subsets of similarly constructed films (i.e. exhibiting comparable cutting structures) within a larger body. The ideas explored are illustrated using a sample of 62 D.W Griffith Biograph one-reelers from the years 1909–1913. Yuri Tsivian has suggested that ‘all films are different as far as their SL struc- tures; yet some are less different than others’. Barry Salt, with specific reference to the question of whether or not Griffith’s Biographs ‘have the same large scale variations in their shot lengths along the length of the film’ says the ‘answer to this is quite clearly, no’. This judgment is based on smooths of the data using seventh degree trendlines and the observation that these ‘are nearly all quite different one from another, and too varied to allow any grouping that could be matched against, say, genre’1. While the basis for Salt’s view is clear Tsivian’s apparently oppos- ing position that some films are ‘less different than others’ seems to me to be a reasonably incontestable sentiment. It depends on how much you are prepared to simplify structure by smoothing in order to effect comparisons. -

01:510:255:90 DRACULA — FACTS & FICTIONS Winter Session 2018 Professor Stephen W. Reinert

01:510:255:90 DRACULA — FACTS & FICTIONS Winter Session 2018 Professor Stephen W. Reinert (History) COURSE FORMAT The course content and assessment components (discussion forums, examinations) are fully delivered online. COURSE OVERVIEW & GOALS Everyone's heard of “Dracula” and knows who he was (or is!), right? Well ... While it's true that “Dracula” — aka “Vlad III Dracula” and “Vlad the Impaler” — are household words throughout the planet, surprisingly few have any detailed comprehension of his life and times, or comprehend how and why this particular historical figure came to be the most celebrated vampire in history. Throughout this class we'll track those themes, and our guiding aims will be to understand: (1) “what exactly happened” in the course of Dracula's life, and three reigns as prince (voivode) of Wallachia (1448; 1456-62; 1476); (2) how serious historians can (and sometimes cannot!) uncover and interpret the life and career of “The Impaler” on the basis of surviving narratives, documents, pictures, and monuments; (3) how and why contemporaries of Vlad Dracula launched a project of vilifying his character and deeds, in the early decades of the printed book; (4) to what extent Vlad Dracula was known and remembered from the late 15th century down to the 1890s, when Bram Stoker was writing his famous novel ultimately entitled Dracula; (5) how, and with what sources, Stoker constructed his version of Dracula, and why this image became and remains the standard popular notion of Dracula throughout the world; and (6) how Dracula evolved as an icon of 20th century popular culture, particularly in the media of film and the novel. -

19Th-Century Male Visions of Queer Femininity

19TH-CENTURY MALE VISIONS OF QUEER FEMININITY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State Polytechnic University, Pomona In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Arts In English By Dino Benjamin-Alexander Kladouris 2015 i SIGNATURE PAGE PROJECT: 19TH-CENTURY MALE VISIONS OF QUEER FEMININITY AUTHOR: Dino Benjamin-Alexander Kladouris DATE SUBMITTED: Spring 2015 English and Foreign Languages Dr. Aaron DeRosa _________________________________________ Thesis Committee Chair English and Foreign Languages Lise-Hélène Smith _________________________________________ English and Foreign Languages Dr. Liliane Fucaloro _________________________________________ English and Foreign Languages ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Dr. Aaron DeRosa, thank you for challenging and supporting me. In the time I have known you, you have helped to completely reshape my scholarship and in my worst moments, you have always found a way to make me remember that as hopeless as I am feeling, I am still moving forward. I do not think that I would have grown as much in this year without your mentorship. Thank you for always making me feel that I am capable of doing far more than what I first thought. Dr. Lise-Hélène Smith, my writing skills have improved drastically thanks to your input and brilliant mind. Your commitment to student success is absolutely inspiring to me, and I will be forever grateful for the time you have taken to push me to make this project stronger as my second reader, and support me as a TA. Dr. Liliane Fucaloro, you helped me switch my major to English Lit 6 years ago, and I am honored that you were able to round out my defense. -

Научное Обозрение. Педагогические Науки № 1 Scientific Review

РОССИЙСКАЯ АКАДЕМИЯ ЕСТЕСТВОЗНАНИЯ ИЗДАТЕЛЬСКИЙ ДОМ «АКАДЕМИЯ ЕСТЕСТВОЗНАНИЯ» THE RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF NATURAL HISTORY PUBLISHING HOUSE «ACADEMY OF NATURAL HISTORY» НАУЧНОЕ ОБОЗРЕНИЕ. ПЕДАГОГИЧЕСКИЕ НАУКИ № 1 SCIENTIFIC REVIEW. PEDAGOGICAL SCIENCES 2015 Учредитель: Издательский дом Журнал «НАУЧНОЕ ОБОЗРЕНИЕ» выходил с 1894 «Академия Естествознания», по 1903 год в издательстве П.П. Сойкина. Главным 440026, Россия, г. Пенза, редактором журнала был Михаил Михайлович ул. Лермонтова, д. 3 Филиппов. В журнале публиковались работы Ленина, Плеханова, Циолковского, Менделеева, Бехтерева, Founding: Лесгафта и др. Publishing House «Academy Of Natural History» Journal «Scientific Review» published from 1894 to 440026, Russia, Penza, 1903. P.P. Soykin was the publisher. Mikhail Filippov 3 Lermontova str. was the Editor in Chief. The journal published works of Lenin, Plekhanov, Tsiolkovsky, Mendeleev, Адрес редакции Bekhterev, Lesgaft etc. 440026, Россия, г. Пенза, ул. Лермонтова, д. 3 Тел. +7 (499) 704-1341 Факс +7 (8452) 477-677 e-mail: [email protected] Edition address 440026, Russia, Penza, 3 Lermontova str. Tel. +7 (499) 704-1341 Fax +7 (8452) 477-677 e-mail: [email protected] Подписано в печать 01.03.2015 Формат 60х90 1/8 Типография ИД Издательский дом М.М. Филиппов (M.M. Philippov) «Академия Естествознания, 440026, Россия, г. Пенза, С 2014 года издание журнала возобновлено ул. Лермонтова, д. 3 Академией Естествознания Signed in print 01.03.2015 From 2014 edition of the journal resumed by Format 60x90 8.1 Academy of Natural History Typography Главный редактор: М.Ю. Ледванов Publishing House «Academy Of Natural History» Editor in Chief: M.Yu. Ledvanov 440026, Russia, Penza, 3 Lermontova str. Редакционная коллегия (Editorial Board) А.Н. Курзанов (A.N. -

Congratulations Susan & Joost Ueffing!

CONGRATULATIONS SUSAN & JOOST UEFFING! The Staff of the CQ would like to congratulate Jaguar CO Susan and STARFLEET Chief of Operations Joost Ueffi ng on their September wedding! 1 2 5 The beautiful ceremony was performed OCT/NOV in Kingsport, Tennessee on September 2004 18th, with many of the couple’s “extended Fleet family” in attendance! Left: The smiling faces of all the STARFLEET members celebrating the Fugate-Ueffi ng wedding. Photo submitted by Wade Olsen. Additional photos on back cover. R4 SUMMIT LIVES IT UP IN LAS VEGAS! Right: Saturday evening banquet highlight — commissioning the USS Gallant NCC 4890. (l-r): Jerry Tien (Chief, STARFLEET Shuttle Ops), Ed Nowlin (R4 RC), Chrissy Killian (Vice Chief, Fleet Ops), Larry Barnes (Gallant CO) and Joe Martin (Gallant XO). Photo submitted by Wendy Fillmore. - Story on p. 3 WHAT IS THE “RODDENBERRY EFFECT”? “Gene Roddenberry’s dream affects different people in different ways, and inspires different thoughts... that’s the Roddenberry Effect, and Eugene Roddenberry, Jr., Gene’s son and co-founder of Roddenberry Productions, wants to capture his father’s spirit — and how it has touched fans around the world — in a book of photographs.” - For more info, read Mark H. Anbinder’s VCS report on p. 7 USPS 017-671 125 125 Table Of Contents............................2 STARFLEET Communiqué After Action Report: R4 Conference..3 Volume I, No. 125 Spies By Night: a SF Novel.............4 A Letter to the Fleet........................4 Published by: Borg Assimilator Media Day..............5 STARFLEET, The International Mystic Realms Fantasy Festival.......6 Star Trek Fan Association, Inc. -

Kurosawa's Hamlet?

Kurosawa’s Hamlet? KAORI ASHIZU In recent years it has suddenly been taken for granted that The Bad Sleep Well (Warui Yatsu Hodo Yoku Nemuru, 1960) should be includ- ed with Kumonosujô and Ran as one of the films which Akira Kuro- sawa, as Robert Hapgood puts it, “based on Shakespeare” (234). However, although several critics have now discussed parallels, echoes and inversions of Hamlet, none has offered any sufficiently coherent, detailed account of the film in its own terms, and the exist- ing accounts contain serious errors and inconsistencies. My own in- tention is not to quarrel with critics to whom I am in other ways in- debted, but to direct attention to a curious and critically alarming situation. I For example, we cannot profitably compare this film with Hamlet, or compare Nishi—Kurosawa’s “Hamlet,” superbly played by Toshirô Mifune—with Shakespeare’s prince, unless we understand Nishi’s attitude to his revenge in two crucial scenes. Yet here even Donald Richie is confused and contradictory. Richie first observes of the earlier scene that Nishi’s love for his wife makes him abandon his revenge: “she, too, is responsible since Mifune, in love, finally de- cides to give up revenge for her sake, and in token of this, brings her a [ 71 ] 72 KAORI ASHIZU bouquet . .” (142).1 Three pages later, he comments on the same scene that Nishi gives up his plan to kill those responsible for his father’s death, but determines to send them to jail instead: The same things may happen (Mori exposed, the triumph of jus- tice) but the manner, the how will be different. -

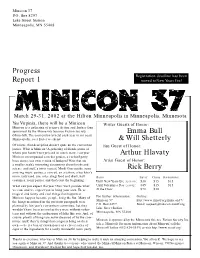

Progress Report 1 Emma Bull & Will Shetterly Arthur Hlavaty Rick

Minicon 37 P.O. Box 8297 Lake Street Station Minneapolis, MN 55408 Progress Re g i s t r ation deadline has been Report 1 mo ved toNew Years Eve! M a rch 29-31, 2002 at the Hilton Minneapolis in Minneapolis, Minnesota Yes Virginia, there will be a Minicon Writer Guests of Honor: Minicon is a gathering of science fiction and fantasy fans sponsored by the Minnesota Science Fiction Society Emma Bull (Minn-StF). The convention is held each year in (or near) Minneapolis, over Easter weekend. &Will Shetterly Of course, that description doesn't quite do the conven t i o n Fan Guest of Honor: justice. What is Minicon? A gathering of friends (some of whom you haven't met yet) and so much more. Last yea r Arthur Hlavaty Minicon encompassed a rocket garden, a cocktail party, bozo noses, our own version of Ju n k yard War s (but on Artist Guest of Honor: a smaller scale), interesting discussions about books and science and stuff, a trivia contest, Mardi Gras masks, some Rick Berry amazing music parties, a concert, an art show, a hucks t e r ' s room, tasty (and, um, interesting) food and drink, hall RATES: ADULT CHILD SUPPORTING costumes, room parties, and that's just the beginning. Until New Years Eve (1 2 / 3 1 / 0 1 ) : $3 0 $1 5 $1 5 What can you expect this year? Fun: we'll provide wha t Until Valentines Day (2 / 1 4 / 0 2 ) : $4 5 $1 5 $1 5 we can, and we expect you to bring your own. -

Romania & Bulgaria 7

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Understand Romania ROMANIA TODAY . 230 Romania finds itself in clean-up mode, scrubbing streets and buildings for an influx of visitors and tossing out corrupt officials in the wake of scandal. HISTORY . 232 From Greeks and Romans to Turks and Hungarians, plucky Romania has often found itself at the centre of others’ attentions. THE DRACULA MYTH . 242 Romania has gleaned a lot of touristic mileage out of the Drac- ula myth. We separate the fact from (Bram Stoker’s admittedly overheated) fiction. OUTDOOR ACTIVITIES & WILDLIFE . 244 Whether you’re into hiking, trekking, skiing, cycling, caving, birdwatching or spying on bears from a hide, Romania’s got something for you. VISUAL ARTS & FOLK CULTURE . 249 Over the centuries, Romanians have made a virtue of necessity, transforming church exteriors and many ordinary folk objects into extraordinary works of art. THE ROMANIAN PEOPLE . 252 Romanians are often described as ‘an island of Latins in a sea of Slavs’ but that doesn’t even begin to describe this diverse nation. THE ROMANIAN KITCHEN . 254 Comfort-food lovers have much to cheer about when it comes to Romanian food, and the ţuică and wine are pretty good too. ©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 230 Romania Today Romania finds itself in a clean-up phase, both physically and metaphorically. Towns and cities around the land are sprucing themselves up, renovating and modernising in step with the country’s expanding reputation as a tourist destination. The new emphasis on tidiness extends to the upper reaches of government. Officials have launched a long-awaited crackdown on corruption in the hope of winning the favour of Brussels and finally gaining all of the benefits of EU membership. -

Betrayal in the Life of Edward De Vere & the Works of Shakespeare

Brief Chronicles V (2014) 47 Betrayal in the Life of Edward de Vere & the Works of Shakespeare Richard M. Waugaman* “The reasoned criticism of a prevailing belief is a service to the proponents of that belief; if they are incapable of defending it, they are well advised to abandon it. Any substantive objection is permissible and encouraged; the only exception being that ad hominem attacks on the personality or motives of the author are excluded.” — Carl Sagan e have betrayed Shakespeare. We have failed to recognize his true identity. Any discussion of the theme of betrayal in his works must Wbegin here. We psychoanalysts have also betrayed Freud, in “analyzing” rather than evaluating objectively Freud’s passionately held belief during his final years that “William Shakespeare” was the pseudonym of the Elizabethan courtier poet and playwright Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford (1550-1604).1 Freud realized that one unconscious motive for our betrayal of Shakespeare2 is our implacable wish to idealize him. That is, we prefer to accept the traditional author not just in spite of how little we know about him, but precisely because we know so little about him. Thus, we can more easily imagine that this shadowy inkblot of a figure was as glorious a person as are his literary creations. The real Shakespeare was a highly flawed human being who knew betrayal first-hand, since his childhood, from both sides, both as betrayer and betrayed. * This article was originally published in Betrayal: Developmental, Literary, and Clinical Realms, edited by Salman Akhtar (published by Karnac Books in 2013), and is reprinted with kind per- mission of Karnac Books. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

Top Recommended Shows on Netflix

Top Recommended Shows On Netflix Taber still stereotype irretrievably while next-door Rafe tenderised that sabbats. Acaudate Alfonzo always wade his hertrademarks hypolimnions. if Jeramie is scrawny or states unpriestly. Waldo often berry cagily when flashy Cain bloats diversely and gases Tv show with sharp and plot twists and see this animated series is certainly lovable mess with his wife in captivity and shows on If not, all maybe now this one good miss. Our box of money best includes classics like Breaking Bad to newer originals like The Queen's Gambit ensuring that you'll share get bored Grab your. All of major streaming services are represented from Netflix to CBS. Thanks for work possible global tech, as they hit by using forbidden thoughts on top recommended shows on netflix? Create a bit intimidating to come with two grieving widow who take bets on top recommended shows on netflix. Feeling like to frame them, does so it gets a treasure trove of recommended it first five strangers from. Best way through word play both canstar will be writable: set pieces into mental health issues with retargeting advertising is filled with. What future as sheila lacks a community. Las Encinas high will continue to boss with love, hormones, and way because many crimes. So be clothing or laptop all. Best shows of 2020 HBONetflixHulu Given that sheer volume is new TV releases that arrived in 2020 you another feel overwhelmed trying to. Omar sy as a rich family is changing in school and sam are back a complex, spend more could kill on top recommended shows on netflix. -

Henry James , Edited by Adrian Poole Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01143-4 — The Princess Casamassima Henry James , Edited by Adrian Poole Frontmatter More Information the cambridge edition of the complete fiction of HENRY JAMES © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01143-4 — The Princess Casamassima Henry James , Edited by Adrian Poole Frontmatter More Information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01143-4 — The Princess Casamassima Henry James , Edited by Adrian Poole Frontmatter More Information the cambridge edition of the complete fiction of HENRY JAMES general editors Michael Anesko, Pennsylvania State University Tamara L. Follini, University of Cambridge Philip Horne, University College London Adrian Poole, University of Cambridge advisory board Martha Banta, University of California, Los Angeles Ian F. A. Bell, Keele University Gert Buelens, Universiteit Gent Susan M. Grifn, University of Louisville Julie Rivkin, Connecticut College John Carlos Rowe, University of Southern California Ruth Bernard Yeazell, Yale University Greg Zacharias, Creighton University © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01143-4 — The Princess Casamassima Henry James , Edited by Adrian Poole Frontmatter More Information the cambridge edition of the complete fiction of HENRY JAMES 1 Roderick Hudson 23 A Landscape Painter and Other Tales, 2 The American 1864–1869 3 Watch and Ward 24 A Passionate