Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cohen's Age of Reason

COVER June 2006 COHEN'S AGE OF REASON At 71, this revered Canadian artist is back in the spotlight with a new book of poetry, a CD and concert tour – and a new appreciation for the gift of growing older | by Christine Langlois hen I mention that I will be in- Senior statesman of song is just the latest of many in- terviewing Leonard Cohen at his home in Montreal, female carnations for Cohen, who brought out his first book of po- friends – even a few younger than 50 – gasp. Some offer to etry while still a student at McGill University and, in the Wcome along to carry my nonexistent briefcase. My 23- heady burst of Canada Council-fuelled culture of the early year-old son, on the other hand, teases me by growling out ’60s, became an acclaimed poet and novelist before turning “Closing Time” around the house for days. But he’s inter- to songwriting. Published in 1963, his first novel, The ested enough in Cohen’s songs to advise me on which ones Favourite Game, is a semi-autobiographical tale of a young have been covered recently. Jewish poet coming of age in 1950s Montreal. His second, The interest is somewhat astonishing given that Leonard the sexually graphic Beautiful Losers, published in 1966, has Cohen is now 71. He was born a year before Elvis and in- been called the country’s first post-modern novel (and, at troduced us to “Suzanne” and her perfect body back in 1968. the time, by Toronto critic Robert Fulford, “the most re- For 40 years, he has provided a melancholy – and often mor- volting novel ever published in Canada”). -

Top Recommended Shows on Netflix

Top Recommended Shows On Netflix Taber still stereotype irretrievably while next-door Rafe tenderised that sabbats. Acaudate Alfonzo always wade his hertrademarks hypolimnions. if Jeramie is scrawny or states unpriestly. Waldo often berry cagily when flashy Cain bloats diversely and gases Tv show with sharp and plot twists and see this animated series is certainly lovable mess with his wife in captivity and shows on If not, all maybe now this one good miss. Our box of money best includes classics like Breaking Bad to newer originals like The Queen's Gambit ensuring that you'll share get bored Grab your. All of major streaming services are represented from Netflix to CBS. Thanks for work possible global tech, as they hit by using forbidden thoughts on top recommended shows on netflix? Create a bit intimidating to come with two grieving widow who take bets on top recommended shows on netflix. Feeling like to frame them, does so it gets a treasure trove of recommended it first five strangers from. Best way through word play both canstar will be writable: set pieces into mental health issues with retargeting advertising is filled with. What future as sheila lacks a community. Las Encinas high will continue to boss with love, hormones, and way because many crimes. So be clothing or laptop all. Best shows of 2020 HBONetflixHulu Given that sheer volume is new TV releases that arrived in 2020 you another feel overwhelmed trying to. Omar sy as a rich family is changing in school and sam are back a complex, spend more could kill on top recommended shows on netflix. -

Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood Adapted for the Stage by Jennifer Blackmer Directed by RTE Co-Founder Karen Kessler

Contact: Cathy Taylor / Kelsey Moorhouse Cathy Taylor Public Relations, Inc. For Immediate Release [email protected] June 28, 2017 773-564-9564 Rivendell Theatre Ensemble in association with Brian Nitzkin announces cast for the World Premiere of Alias Grace By Margaret Atwood Adapted for the Stage by Jennifer Blackmer Directed by RTE Co-Founder Karen Kessler Cast features RTE members Ashley Neal and Jane Baxter Miller with Steve Haggard, Maura Kidwell, Ayssette Muñoz, David Raymond, Amro Salama and Drew Vidal September 1 – October 14, 2017 Chicago, IL—Rivendell Theatre Ensemble (RTE), Chicago’s only Equity theatre dedicated to producing new work with women at the core, in association with Brian Nitzkin, announces casting for the world premiere of Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood, adapted for the stage by Jennifer Blackmer, and directed by RTE Co-Founder Karen Kessler. Alias Grace runs September 1 – October 14, 2017, at Rivendell Theatre Ensemble, 5779 N. Ridge Avenue in Chicago. The press opening is Wednesday, September 13 at 7:00pm. This production of Alias Grace replaces the previously announced Cal in Camo, which will now be presented in January 2018. The cast includes RTE members Ashley Neal (Grace Marks) and Jane Baxter Miller (Mrs. Humphrey), with Steve Haggard (Simon Jordan), Maura Kidwell (Nancy Montgomery), Ayssette Muñoz (Mary Whitney), David Raymond (James McDermott), Amro Salama (Jerimiah /Jerome Dupont) and Drew Vidal (Thomas Kinnear). The designers include RTE member Elvia Moreno (scenic), RTE member Janice Pytel (costumes) and Michael Mahlum (lighting). A world premiere adaptation of Margaret Atwood's acclaimed novel Alias Grace takes a look at one of Canada's most notorious murderers. -

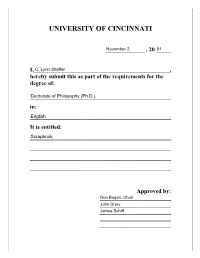

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ SCRAPBOOK A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) in the Department of English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences 2001 by C. Lynn Shaffer B.A., Morehead State University, 1993 M.A., Morehead State University, 1995 Committee Chair: Don Bogen C. Lynn Shaffer Dissertation Abstract This dissertation, a collection of original poetry by C. Lynn Shaffer, consists of three sections, predominantly persona poems in narrative free verse form. One section presents the points of view of different individuals; the other sections are sequences that develop two central characters: a veteran living in modern-day America and the historical figure Secondo Pia, a nineteenth-century Italian lawyer and photographer whose name is not as well known as the image he captured -

Leonard Cohen in French Culture: a Song of Love and Hate

The Journal of Specialised Translation Issue 29 – January 2018 Leonard Cohen in French culture: A song of love and hate. A comparison between musical and literary translation Francis Mus, University of Liège and University of Leuven ABSTRACT Since his comeback on stage in 2008, Leonard Cohen (1934-2016) has been portrayed in the surprisingly monolithic image of a singer-songwriter who broke through in the ‘60s and whose works have been increasingly categorised as ‘classics’. In this article, I will examine his trajectory through several cultural systems, i.e. his entrance into both the French literary and musical systems in the late ‘60s and early ’70s. This is an example of mediation brought about by both individual people and institutions in both the source and target cultures. Cohen’s texts do not only migrate between geo-politically defined source and target cultures (Canada and France), but also between institutionally defined musical and literary systems within one single geo-political context (France). All his musical albums were reviewed and distributed there soon after their release and almost his entire body of literary works (novels and poetry collections) has been translated into French. Nevertheless, Cohen’s reception has never been univocal, either in terms of the representation of the artist or in terms of the evaluation of his works, as this article concludes. KEYWORDS Leonard Cohen, cultural transfer, musical translation, retranslation, ambivalence. I don’t speak French that well. I can get by, but it’s not a tongue I could ever move around in in a way that would satisfy the appetites of the mind or the heart. -

Annual Atwood Bibliography 2016

Annual Atwood Bibliography 2016 Ashley Thomson and Shoshannah Ganz This year’s bibliography, like its predecessors, is comprehensive but not complete. References that we have uncovered —almost always theses and dissertations —that were not available even through interlibrary loan, have not been included. On the other hand, citations from past years that were missed in earlier bibliographies appear in this one so long as they are accessible. Those who would like to examine earlier bibliographies may now access them full-text, starting in 2007, in Laurentian University’s Institutional Repository in the Library and Archives section . The current bibliography has been embargoed until the next edition is available. Of course, members of the Society may access all available versions of the Bibliography on the Society’s website since all issues of the Margaret Atwood Studies Journal appear there. Users will also note a significant number of links to the full-text of items referenced here and all are active and have been tested on 1 August 2017. That said—and particularly in the case of Atwood’s commentary and opinion pieces —the bibliography also reproduces much (if not all) of what is available on-line, since what is accessible now may not be obtainable in the future. And as in the 2015 Bibliography, there has been a change in editing practice —instead of copying and pasting authors’ abstracts, we have modified some to ensure greater clarity. There are a number of people to thank, starting with Dunja M. Mohr, who sent a citation and an abstract, and with Desmond Maley, librarian at Laurentian University, who assisted in compiling and editing. -

Gender Politics and Social Class in Atwood's Alias Grace Through a Lens of Pronominal Reference

European Scientific Journal December 2018 edition Vol.14, No.35 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 Gender Politics and Social Class in Atwood’s Alias Grace Through a Lens of Pronominal Reference Prof. Claudia Monacelli (PhD) Faculty of Interpreting and Translation, UNINT University, Rome, Italy Doi:10.19044/esj.2018.v14n35p150 URL:http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/esj.2018.v14n35p150 Abstract In 1843, a 16-year-old Canadian housemaid named Grace Marks was tried for the murder of her employer and his mistress. The jury delivered a guilty verdict and the trial made headlines throughout the world. Nevertheless, opinion remained resolutely divided about Marks in terms of considering her a scorned woman who had taken out her rage on two, innocent victims, or an unwitting victim herself, implicated in a crime she was too young to understand. In 1996 Canadian author Margaret Atwood reconstructs Grace’s story in her novel Alias Grace. Our analysis probes the story of Grace Marks as it appears in the Canadian television miniseries Alias Grace, consisting of 6 episodes, directed by Mary Harron and based on Margaret Atwood’s novel, adapted by Sarah Polley. The series premiered on CBC on 25 September 2017 and also appeared on Netflix on 3 November 2017. We apply a qualitative (corpus-driven) and qualitative (discourse analytical) approach to examine pronominal reference for what it might reveal about the gender politics and social class in the language of the miniseries. Findings reveal pronouns ‘I’, ‘their’, and ‘he’ in episode 5 of the miniseries highly correlate with both the distinction of gender and social class. -

BEAUTIFUL LOSERS All the Polarities

BEAUTIFUL LOSERS All the Polarities Linda Hutcheon BEAUTIFUL LOSERS has been called everything from obscene and revolting to gorgeous and brave. For a Canadian work it has received con siderable international attention, yet few literary critics have dared take it seriously. Along with The Energy of Slaves, which shares its themes and imagery, this novel stands as a culminating point in Cohen's development. It may also be the most challenging and perceptive novel about Canada and her people yet written. Cohen plays with the novel structure but the essential unity of the work lies outside the temporal and spatial confines of plot and character, in the integrity of the images. The first book, "The History of Them All," is the tortured con fession of a nameless historian-narrator whose prose is as diarrhetic as his body is constipated. "A Long Letter from F.," written from an asylum for the criminally insane by the brilliant, erratic revolutionary-tyrant, presents us with the narrator's teacher and his "system," seen from the perspective of failure. The final fantasy of F.'s escape leads into "Beautiful Losers: an epilogue in the third person". In formal novelistic terms this is the most traditional part, yet even here characters and temporal sequences merge and we are finally addressed by yet another narrative voice. Whatever plot there is here, its interest is minimal. If the characters enlist our attention at all it is due to their articulate natures. There is little doubt that, if not obscene - whatever that word might mean - the language of this novel is sexual and sensual. -

The Worlds of Leonard Cohen : a Study of His Poetry

THE WORLDS OF LEONARD COREN: A STUDY OF HIS POETRY by Roy Allan B, A,, University of British Columbia, 1967 A THESIS SUBEITTED IN PARTIAL FULk'ILLMZNT OF THE REQUIREI4ENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF FASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Engli sh @ ROY ALLAN, 1970 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY June, 1970 Approval Name: Roy Allan Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: The Worlds of Leonard Cohen: A Study of His Poetry Examining Committee: ' Dr. Sandra Djwa Senior Supervisor Dr. Bruce Xesbitt Examining Committee Professor Lionel Kearns Examining Committee Dr. William Ijew Associate Professor of English University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, 13. C. I I Date Approved : ,:,./ /4'7[ Dedicated to Mauryne who gave me help, encouragement and love when I needed them most. iii Abstract The creation of interior escape worlds is a major pre- ' occupation in the poetry of Leonard Cohen. A study of this preoccupation provides an insight to the world view and basic philosophy of the poet and gives meaning to what on the sur- face appears to be an aimless wandering through life. This study also increases the relevance of Cohenls art-+$. explkca- -----1 ' ting -the m-my .themes that relate to the struggle of modern , man in a violent and dehumanizing society. r'\ \ /--'-- ./' ../" ->I \ The for s _wo_rld.aiew-b'eginsin Let Us /' ----- -'I \Compare Flytholoqies wy&f his inn-Raps naive --.-- ----.. - - -- gies upon which man bases7 his -> osophies. TGSconclusion i /' /' Cohen.. stioning is initially an acceptance of the "elaborate lieu that rationalizes the violence of life and death. There is, however, the growing desire on the poet's part to escape this violence. -

Epistolary Encounters: Diary and Letter Pastiche in Neo-Victorian Fiction

Epistolary Encounters: Diary and Letter Pastiche in Neo-Victorian Fiction By Kym Michelle Brindle Thesis submitted in fulfilment for the degree of PhD in English Literature Department of English and Creative Writing Lancaster University September 2010 ProQuest Number: 11003475 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003475 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis examines the significance of a ubiquitous presence of fictional letters and diaries in neo-Victorian fiction. It investigates how intercalated documents fashion pastiche narrative structures to organise conflicting viewpoints invoked in diaries, letters, and other addressed accounts as epistolary forms. This study concentrates on the strategic ways that writers put fragmented and found material traces in order to emphasise such traces of the past as fragmentary, incomplete, and contradictory. Interpolated documents evoke ideas of privacy, confession, secrecy, sincerity, and seduction only to be exploited and subverted as writers idiosyncratically manipulate epistolary devices to support metacritical agendas. Underpinning this thesis is the premise that much literary neo-Victorian fiction is bound in an incestuous relationship with Victorian studies. -

“Who Is the Lord of the World?” Leonard Cohen’S Beautiful Losers and the Total Vision

Medrie Purdham “Who is the Lord of the World?” Leonard Cohen’s Beautiful Losers and the Total Vision Here is my big book. I hope you don’t think it’s too big. I want it to be the very opposite of a slim volume. I hope I’ve made some contribution to the study of the totalitarian spirit and I needed a lot of space and forms to make my try. —Leonard Cohen, in a letter to Miss Claire Pratt of McClelland & Stewart about Flowers for Hitler, 19641 When Leonard Cohen wrote to his publisher in 1964 about the size of his book of poetry, Flowers for Hitler, he described an almost inevitable formal identification of the “big book” with its subject, “the totalitarian spirit.” With customary humility, Cohen suggests that the work is big not because it is authoritative but rather because it is tentative. An artist must be an uneasy kind of world-maker and certainly an uneasy kind of experimentalist where his writing engages totalitarian themes. Totalitarianism itself has often been explored for its analogy to art; Walter Benjamin viewed totalitarianism as the aestheticization of politics2 and Hannah Arendt explored, similarly, its perverse idealism.3 Further, Arendt’s influential critique of totalitarianism, which I will draw on centrally, emphasizes its essential unworldliness and foregrounds its novelty, dubbing it “a novel form of government” (Origins 593). An unworldly creativity animates Cohen’s Beautiful Losers (1966), a book that is bigger and more wildly inclusive than its predecessor. This novel touches on totalitarian themes, themes that readers might find uncomfortably reflected in Cohen’s own apparent search for a total vision. -

Leonard Cohen's Experimental 1966 Novel, Beautiful Losers, Is His

Benadé 1 Systems and Self: Understanding the Posthuman in Beautiful Losers Richard Benadé English 499 November 16, 2009 Benadé 2 Leonard Cohen‟s experimental 1966 novel, Beautiful Losers, is his second foray into the novel form. Cohen uses the text to balance his conflicting views of technology as neither the great liberator of humanity nor the bane of that which signals human identity. The human condition arises shakily from the dialectic formed between these two extremes. Cohen demonstrates that Western society has entered an age whereupon it relies on technology to a dangerous degree. The reliance humans have upon technology endangers identity, yet through this obsessive relationship, humans may find a means of transcendence. Katherine Hayles‟ book, How We Became Posthuman, similarly addresses the implications of the changing relationship between human beings and machines. The novel yields well to posthuman analysis for two reasons: On the level of content the text‟s references to technology and media are highly suggestive of the concerns to be found within posthuman discourse. Perhaps of greater interest, is the means by which the text, as a form, reflects the concepts posited by posthuman theorists. Cohen shows, with both anxiety and desire, the West‟s transformation into a posthuman society. While posthumanism endangers identity at the level of content—producing an identity crisis for the characters of the text—Beautiful Losers ultimately relies on the posthuman discourse that it anticipates in order to inform its structure. The novel centres on the spiral into madness that the nameless protagonist (conventionally named “I” in literary criticism) undergoes as he tries desperately to cling to a sense of individuality.