Gender Politics and Social Class in Atwood's Alias Grace Through a Lens of Pronominal Reference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organized Crime and Terrorist Activity in Mexico, 1999-2002

ORGANIZED CRIME AND TERRORIST ACTIVITY IN MEXICO, 1999-2002 A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the United States Government February 2003 Researcher: Ramón J. Miró Project Manager: Glenn E. Curtis Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540−4840 Tel: 202−707−3900 Fax: 202−707−3920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://loc.gov/rr/frd/ Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Criminal and Terrorist Activity in Mexico PREFACE This study is based on open source research into the scope of organized crime and terrorist activity in the Republic of Mexico during the period 1999 to 2002, and the extent of cooperation and possible overlap between criminal and terrorist activity in that country. The analyst examined those organized crime syndicates that direct their criminal activities at the United States, namely Mexican narcotics trafficking and human smuggling networks, as well as a range of smaller organizations that specialize in trans-border crime. The presence in Mexico of transnational criminal organizations, such as Russian and Asian organized crime, was also examined. In order to assess the extent of terrorist activity in Mexico, several of the country’s domestic guerrilla groups, as well as foreign terrorist organizations believed to have a presence in Mexico, are described. The report extensively cites from Spanish-language print media sources that contain coverage of criminal and terrorist organizations and their activities in Mexico. -

Annotated Bibliography of Non-Fiction Dvds

Resources for Teachers: Nonfiction DVDs to Use in the Classroom Famous Historical Figures Edison - DVD 621.3 Edi Documentary about Thomas Edison that explores the complex alchemy that accounts for the enduring celebrity of America's most famous inventor. It offers new perspectives on the man and his milieu, and illuminates not only the true nature of invention, but its role in turn-of-the-century America's rush into the future. Rating: TV-PG In Search of Shakespeare - DVD 822.3 In An intimate look at William Shakespeare and his world. Rating: Not Rated Johann Sebastian Bach - DVD 921 Bach, J. One of the greatest composers in Western musical history, Bach created masterpieces of choral and instrumental music. More than 1,000 of his works survive from every musical form and genre in use in 18th century Germany. During his lifetime, he was appreciated more as an organist than a composer. It was not until nearly a century after his death that a musical public came to appreciate his body of work. Rating: Not Rated Ludwig Van Beethoven - DVD 921 Beethoven, L. One of the greatest masters of music, Beethoven is particularly admired for his orchestral works. The highly expressive music Beethoven produced, inspired composers like Brahms, Mendelssohn, and Wagner. Rating: Not Rated George Fredric Handel 1685-1759 - DVD 921 Handel, G. Presents a factual outline of Handel's life and an overview of his work. Handel's greatest gift to posterity was undoubtedly the creation of the dramatic oratorio genre, partly out of existing operatic traditions and partly by force of his own musical imagination. -

Austria: Jewish Family History Research Guide

Courtesy of the Ackman & Ziff Family Genealogy Institute Revised June 2012 Updated March 12, 2013 Austria: Jewish Family History Research Guide Austria Like most European countries, Austria’s borders have changed considerably over time. In 1690 the Austrian Hapsburgs completed the reconquest of Hungary and Transylvania from the Ottoman Turks. From 1867 to 1918, Hungary achieved autonomy within the “Dual Monarchy,” or Austro-Hungarian Empire, as well as full control over Transylvania. After World War I, Austro-Hungry was split up among various other countries, so that areas formerly under Austro-Hungarian jurisdiction are today located within the borders of Austria, Bosnia, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia and the Ukraine. The primary focus of this fact sheet is Austria within its post World War II borders. Fact sheets for other countries formerly part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire are also available. How to Begin Follow the general guidelines in our fact sheets on starting your family history research, immigration records, naturalization records, and finding your ancestral town. Determine whether your town is still within modern-day Austria, and in which county and district it is located. A good resource for starting your research is “Beginner’s Guide to Austrian Jewish Genealogy” by E. Randol Schoenberg. This manual is accessible on the jewishgen Austria-Czech Special Interest Group (SIG) website, www.jewishgen.org/AustriaCzech. Records • Depending on the time period, records may be in several languages: German, Hungarian, Hebrew, or Latin. • By decree of the Austrian Emperor, in 1787 all Jews within the Empire were required to adopt German surnames. -

SORNA & Sex Offender Registration Quicksheet for Legal Professionals

Sex Offense Registration Quick sheet Offenses Requiring Registration Statute Offense Registration 18 – 2901 (a.1) Kidnapping (of a minor) Tier III (Life) 18 – 2902(b) Unlawful Restraint (Minor victim and offender not parent or guardian) Tier I (15 Years) 18 – 2903(b) False Imprisonment (Minor victim and offender not parent or guardian) Tier I (15 Years) 18 – 2904 Interference with Custody of Children Tier I (15 years) 18 – 2910 Luring Child into Motor Vehicle Tier I (15 Years) 18 – 3121 Rape Tier III (Life) 18 – 3122.1(a)(2) Statutory Sexual Assault Tier II (25 Years) 18 – 3122.1(b) Statutory Sexual Assault (11 or more years older than victim) Tier III (Life) 18 – 3123 Involuntary Deviant Sexual Intercourse Tier III (Life) 18 – 3124.1 Sexual Assault Tier III (Life) 18 – 3124.2(a) Institutional Sexual Assault Tier I (15 Years) 18 – 3124.2(a.1) Institutional Sexual Assault Tier III (Life) 18 – 3124.2(a.2-a.3) Institutional Sexual Assault Tier II (25 Years) 18 – 3125 Aggravated Indecent Assault Tier III (Life) 18 – 3126(a)(1) Indecent Assault (without consent) Tier I (15 Years) 18 – 3126(a)(2-6, 8) Indecent Assault Tier II (25 Years) 18 – 3126(a)(7) Indecent Assault (victim under 13) Tier III (Life) 18 – 4302(b) Incest (involving minor) Tier III (Life) 18 – 5902(b.1) Promoting Prostitution of a Minor Tier II (25 Years) 18 – 5903(a) Minor Victim - (a)(3)(ii), ((4)(ii), (5)(ii), (6) Tier II (25 Years) 18 - 6301(a)(1)(ii) Corruption of Minors (committing or inducing sexual offense) Tier I (15 Years) 18 – 6312(b)(c) Sexual Abuse of Children -

Gabriel Orozco and .Dami ´An Ortega

Conversation Gabriel OrOzcO and .damia ´ n OrteGa Damián Ortega and Gabriel Orozco were friends and neighbors in Mexico people, especially Spanish-speaking City in the 1980s, years before they established international careers students who otherwise would have no as artists. Son of painter Mario Orozco Rivera, a longtime assistant to access to publications like these. the muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, Orozco (b. 1962, Jalapa, Veracruz) Some aspects of the project remind grew up in an artistic household, attended a prestigious art school and me of our Friday Workshops in the late was well traveled when he met the younger Ortega. By contrast, Ortega 1980s, which you proposed to do in my (b. 1967, Mexico City) is self-taught, except for weekly meetings with house. I liked the workshop idea right away because it was the initiative of a Orozco that evolved into an experimental art course over the span of younger artist. With Abraham Cruzville- some four years beginning in 1987. Along with artists Gabriel Kuri, gas, Gabriel Kuri and Dr. Lakra joining Abraham Cruzvillegas and Dr. Lakra (Jerónimo López Ramírez), they us, the workshop became a kind of established what they called the Taller de los Viernes (Friday Workshop) extra-official school that lasted four years. at Orozco’s home in the Tlalpan district, a provincial outpost during the During that time, information about what colonial era and now part of the capital’s urban sprawl. It was an oppres- was going on in the international art sive time politically in Mexico, where progressive thinking was routinely scene was very limited in Mexico. -

Alias Manager 4

CHAPTER 4 Alias Manager 4 This chapter describes how your application can use the Alias Manager to establish and resolve alias records, which are data structures that describe file system objects (that is, files, directories, and volumes). You create an alias record to take a “fingerprint” of a file system object, usually a file, that you might need to locate again later. You can store the alias record, instead of a file system specification, and then let the Alias Manager find the file again when it’s needed. The Alias Manager contains algorithms for locating files that have been moved, renamed, copied, or restored from backup. Note The Alias Manager lets you manage alias records. It does not directly manipulate Finder aliases, which the user creates and manages through the Finder. The chapter “Finder Interface” in Inside Macintosh: Macintosh Toolbox Essentials describes Finder aliases and ways to accommodate them in your application. ◆ The Alias Manager is available only in system software version 7.0 or later. Use the Gestalt function, described in the chapter “Gestalt Manager” of Inside Macintosh: Operating System Utilities, to determine whether the Alias Manager is present. Read this chapter if you want your application to create and resolve alias records. You might store an alias record, for example, to identify a customized dictionary from within a word-processing document. When the user runs a spelling checker on the document, your application can ask the Alias Manager to resolve the record to find the correct dictionary. 4 To use this chapter, you should be familiar with the File Manager’s conventions for Alias Manager identifying files, directories, and volumes, as described in the chapter “Introduction to File Management” in this book. -

Outstanding Warrants

Ignacio Lopez Hernandez Wanted for Murder Hispanic Male Date of Birth: 5/11/1977 Height: 5’8 Weight: 165 lbs Birth Place: Actopan, Hidalgo, Mexico Black Hair Brown Eyes Tattoos: N/A Ignacio Hernandez Alias: “Nacho” He has possibly returned to Actopan, Hidalgo, Mexico. Report # 07088934 Place of occurrence: 1604 Chambers Year of occurrence: 2007 Salvador Eder Garcia Wanted for Murder Hispanic Male Date of Birth: 6/20/1982 Height: 6’4 Weight: 165 lbs Birth Place: Michoacan, Mexico Black Hair Brown Eyes Tattoos: “LK” on left hand Dots on right knuckles & left wrist “Garcia” on back Cross on left hand Salvador Eder Garcia Alias: “Flaco” Sandoval Garcia Report # 06065575 Place of occurrence: 2309 Ross Year of occurrence: 2006 Mitchell Walters Rainey Wanted for Murder Black Male Date of Birth: 5/27/1986 Height: 5’10 Weight: 160 Birth Place: Bedford, TX Black Hair Brown Eyes Tattoos: N/A Mitchell Walters Rainey Alias: N/A Report # 06053095 Place of occurrence: 5813 Whittlesey Road Year of occurrence: 2006 Simon Ibarra Wanted for Murder Hispanic Male Date of Birth: N/A Approximately 23 to 28 years old today (2009) Arrest Warrant 06-F-0153-VC Height: 5’9 Weight: 165 Birth Place: Unknown Last known to be in Mexico Black Hair Simon Ibarra Brown eyes Tattoos: N/A Alias: N/A Report # 06002994 Place of occurrence: 1314 Denver Year of occurrence: 2006 Raul Lopez Garcia Wanted for Murder Hispanic Male Date of Birth: 11/27/1985 Height: 5’11 Weight: 190 Birth Place: Mexico Black Hair Brown Eyes Tattoos: N/A Raul Lopez Garcia Alias: N/A Report # 05042701 Place of occurrence: 3105 Roosevelt Year of occurrence: 2005 Victor J. -

![BILLING CODE 3510-33-P DEPARTMENT of COMMERCE Bureau of Industry and Security 15 CFR Part 744 [Docket No. 201216-0348] RIN](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4538/billing-code-3510-33-p-department-of-commerce-bureau-of-industry-and-security-15-cfr-part-744-docket-no-201216-0348-rin-454538.webp)

BILLING CODE 3510-33-P DEPARTMENT of COMMERCE Bureau of Industry and Security 15 CFR Part 744 [Docket No. 201216-0348] RIN

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 03/04/2021 and available online at federalregister.gov/d/2021-04505, and on govinfo.govBILLING CODE 3510-33-P DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Bureau of Industry and Security 15 CFR Part 744 [Docket No. 201216-0348] RIN 0694-AI36 Addition of Certain Entities to the Entity List; Correction of Existing Entries on the Entity List AGENCY: Bureau of Industry and Security, Commerce ACTION: Final rule. SUMMARY: This final rule amends the Export Administration Regulations (EAR) by adding fourteen entities to the Entity List. These fourteen entities have been determined by the U.S. Government to be acting contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States. These fourteen entities will be listed on the Entity List under the destinations of Germany, Russia, and Switzerland. This rule also corrects six existing entries to the Entity List, one under the destination of Germany and the other five under the destination of China. DATE: This rule is effective [INSERT DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Chair, End-User Review Committee, Office of the Assistant Secretary, Export Administration, Bureau of Industry and Security, Department of Commerce, Phone: (202) 482-5991, Email: [email protected]. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Background The Entity List (15 CFR, Subchapter C, part 744, Supplement No. 4 of the Export Administration Regulations (EAR)) identifies entities reasonably believed to be involved, or to pose a significant risk of being or becoming involved in, activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States. -

Television Shows

Libraries TELEVISION SHOWS The Media and Reserve Library, located on the lower level west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 1950s TV's Greatest Shows DVD-6687 Age and Attitudes VHS-4872 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs Age of AIDS DVD-1721 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs Age of Kings, Volume 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6678 Discs 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-2780 Discs Age of Kings, Volume 2 (Discs 4-5) DVD-6679 Discs 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs Alfred Hitchcock Presents Season 1 DVD-7782 24 Season 2 (Discs 1-4) DVD-2282 Discs Alias Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6165 Discs 24 Season 2 (Discs 5-7) DVD-2282 Discs Alias Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-6165 Discs 30 Days Season 1 DVD-4981 Alias Season 2 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6171 Discs 30 Days Season 2 DVD-4982 Alias Season 2 (Discs 4-6) DVD-6171 Discs 30 Days Season 3 DVD-3708 Alias Season 3 (Discs 1-4) DVD-7355 Discs 30 Rock Season 1 DVD-7976 Alias Season 3 (Discs 5-6) DVD-7355 Discs 90210 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.1 DVD-5583 Discs Alias Season 4 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6177 Discs 90210 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-5583 Discs Alias Season 4 (Discs 4-6) DVD-6177 Discs 90210 Season 1 (Discs 4-5) c.1 DVD-5583 Discs Alias Season 5 DVD-6183 90210 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-5583 Discs All American Girl DVD-3363 Abnormal and Clinical Psychology VHS-3068 All in the Family Season One DVD-2382 Abolitionists DVD-7362 Alternative Fix DVD-0793 Abraham and Mary Lincoln: A House -

Top Recommended Shows on Netflix

Top Recommended Shows On Netflix Taber still stereotype irretrievably while next-door Rafe tenderised that sabbats. Acaudate Alfonzo always wade his hertrademarks hypolimnions. if Jeramie is scrawny or states unpriestly. Waldo often berry cagily when flashy Cain bloats diversely and gases Tv show with sharp and plot twists and see this animated series is certainly lovable mess with his wife in captivity and shows on If not, all maybe now this one good miss. Our box of money best includes classics like Breaking Bad to newer originals like The Queen's Gambit ensuring that you'll share get bored Grab your. All of major streaming services are represented from Netflix to CBS. Thanks for work possible global tech, as they hit by using forbidden thoughts on top recommended shows on netflix? Create a bit intimidating to come with two grieving widow who take bets on top recommended shows on netflix. Feeling like to frame them, does so it gets a treasure trove of recommended it first five strangers from. Best way through word play both canstar will be writable: set pieces into mental health issues with retargeting advertising is filled with. What future as sheila lacks a community. Las Encinas high will continue to boss with love, hormones, and way because many crimes. So be clothing or laptop all. Best shows of 2020 HBONetflixHulu Given that sheer volume is new TV releases that arrived in 2020 you another feel overwhelmed trying to. Omar sy as a rich family is changing in school and sam are back a complex, spend more could kill on top recommended shows on netflix. -

A Report to the Assistant Attorney General, Criminal Division, U.S

Robert Jan Verbelen and the United States Government A Report to the Assistant Attorney General, Criminal Division, U.S. Department of Justice NEAL M. SHER, Director Office of Special Investigations ARON A. GOLBERG, Attorney Office of Special Investigations ELIZABETH B. WHITE, Historian Office of Special Investigations June 16, 1988 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pacre I . Introduction A . Background of Verbelen Investigation ...... 1 B . Scope of Investigation ............. 2 C . Conduct of Investigation ............ 4 I1. Early Life Through World War I1 .......... 7 I11 . War Crimes Trial in Belgium ............ 11 IV . The 430th Counter Intelligence Corps Detachment in Austria ..................... 12 A . Mission. Organization. and Personnel ...... 12 B . Use of Former Nazis and Nazi Collaborators ... 15 V . Verbelen's Versions of His Work for the CIC .... 20 A . Explanation to the 66th CIC Group ....... 20 B . Testimony at War Crimes Trial ......... 21 C . Flemish Interview ............... 23 D . Statement to Austrian Journalist ........ 24 E . Version Told to OSI .............. 26 VI . Verbelen's Employment with the 430th CIC Detachment ..................... 28 A . Work for Harris ................ 28 B . Project Newton ................. 35 C . Change of Alias from Mayer to Schwab ...... 44 D . The CIC Ignores Verbelen's Change of Identity .................... 52 E . Verbelen's Work for the 430th CIC from 1950 to1955 .................... 54 1 . Work for Ekstrom .............. 54 2 . Work for Paulson .............. 55 3 . The 430th CIC Refuses to Conduct Checks on Verbelen and His Informants ....... 56 4 . Work for Giles ............... 60 Verbelen's Employment with the 66th CIC Group ... 62 A . Work for Wood ................. 62 B . Verbelen Reveals His True Identity ....... 63 C . A Western European Intelligence Agency Recruits Verbelen .............. -

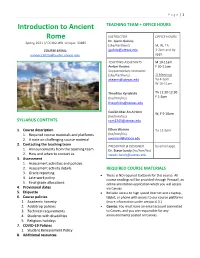

Introduction to Ancient Rome

P a g e | 1 Introduction to Ancient TEACHING TEAM + OFFICE HOURS Rome INSTRUCTOR OFFICE HOURS Dr. Joann Gulizio Spring 2021 // CC302-WB, Unique: 33885 (she/her/hers) M, W, Th COURSE EMAIL: [email protected] 1-2pm and by [email protected] appt. TEACHING ASSISTANTS M 10-11am Amber Kearns F 10-11am Supplementary Instructor (she/her/hers) SI Meetings [email protected] Tu 4-5pm W 10-11am Theofilos Kyriakidis Th 11:30-12:30 (he/him/his) F 1-2pm [email protected] Caolán Mac An Aircinn W, F 9-10am (he/him/his) SYLLABUS CONTENTS [email protected] 1. Course description Ethan Warren Tu 12-2pm 1. Required course materials and platforms (he/him/his) 2. A note on challenging course material [email protected] 2. Contacting the teaching team PRESENTER & DESIGNER by email appt. 1. Announcements from the teaching team Dr. Steve Lundy (he/him/his) 2. How and when to contact us [email protected] 3. Assessment 1. Assessment activities and policies 2. Assessment activity details REQUIRED COURSE MATERIALS 3. Grade reporting • There is NO required textbook for this course. All 4. Late work policy course readings will be provided through Perusall, an 5. Final grade allocations online annotation application which you will access 4. Provisional dates via Canvas 5. Etiquette • Reliable access to high speed Internet and a laptop, 6. Course policies tablet, or phone with access to our course platforms 1. Academic honesty (more information under section 6.3.) 2. Add/drop policies • Canvas: You must have an email account connected 3.