BEAUTIFUL LOSERS All the Polarities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cohen's Age of Reason

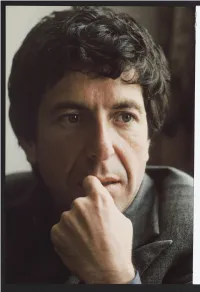

COVER June 2006 COHEN'S AGE OF REASON At 71, this revered Canadian artist is back in the spotlight with a new book of poetry, a CD and concert tour – and a new appreciation for the gift of growing older | by Christine Langlois hen I mention that I will be in- Senior statesman of song is just the latest of many in- terviewing Leonard Cohen at his home in Montreal, female carnations for Cohen, who brought out his first book of po- friends – even a few younger than 50 – gasp. Some offer to etry while still a student at McGill University and, in the Wcome along to carry my nonexistent briefcase. My 23- heady burst of Canada Council-fuelled culture of the early year-old son, on the other hand, teases me by growling out ’60s, became an acclaimed poet and novelist before turning “Closing Time” around the house for days. But he’s inter- to songwriting. Published in 1963, his first novel, The ested enough in Cohen’s songs to advise me on which ones Favourite Game, is a semi-autobiographical tale of a young have been covered recently. Jewish poet coming of age in 1950s Montreal. His second, The interest is somewhat astonishing given that Leonard the sexually graphic Beautiful Losers, published in 1966, has Cohen is now 71. He was born a year before Elvis and in- been called the country’s first post-modern novel (and, at troduced us to “Suzanne” and her perfect body back in 1968. the time, by Toronto critic Robert Fulford, “the most re- For 40 years, he has provided a melancholy – and often mor- volting novel ever published in Canada”). -

Leonard Cohen in French Culture: a Song of Love and Hate

The Journal of Specialised Translation Issue 29 – January 2018 Leonard Cohen in French culture: A song of love and hate. A comparison between musical and literary translation Francis Mus, University of Liège and University of Leuven ABSTRACT Since his comeback on stage in 2008, Leonard Cohen (1934-2016) has been portrayed in the surprisingly monolithic image of a singer-songwriter who broke through in the ‘60s and whose works have been increasingly categorised as ‘classics’. In this article, I will examine his trajectory through several cultural systems, i.e. his entrance into both the French literary and musical systems in the late ‘60s and early ’70s. This is an example of mediation brought about by both individual people and institutions in both the source and target cultures. Cohen’s texts do not only migrate between geo-politically defined source and target cultures (Canada and France), but also between institutionally defined musical and literary systems within one single geo-political context (France). All his musical albums were reviewed and distributed there soon after their release and almost his entire body of literary works (novels and poetry collections) has been translated into French. Nevertheless, Cohen’s reception has never been univocal, either in terms of the representation of the artist or in terms of the evaluation of his works, as this article concludes. KEYWORDS Leonard Cohen, cultural transfer, musical translation, retranslation, ambivalence. I don’t speak French that well. I can get by, but it’s not a tongue I could ever move around in in a way that would satisfy the appetites of the mind or the heart. -

The Worlds of Leonard Cohen : a Study of His Poetry

THE WORLDS OF LEONARD COREN: A STUDY OF HIS POETRY by Roy Allan B, A,, University of British Columbia, 1967 A THESIS SUBEITTED IN PARTIAL FULk'ILLMZNT OF THE REQUIREI4ENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF FASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Engli sh @ ROY ALLAN, 1970 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY June, 1970 Approval Name: Roy Allan Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: The Worlds of Leonard Cohen: A Study of His Poetry Examining Committee: ' Dr. Sandra Djwa Senior Supervisor Dr. Bruce Xesbitt Examining Committee Professor Lionel Kearns Examining Committee Dr. William Ijew Associate Professor of English University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, 13. C. I I Date Approved : ,:,./ /4'7[ Dedicated to Mauryne who gave me help, encouragement and love when I needed them most. iii Abstract The creation of interior escape worlds is a major pre- ' occupation in the poetry of Leonard Cohen. A study of this preoccupation provides an insight to the world view and basic philosophy of the poet and gives meaning to what on the sur- face appears to be an aimless wandering through life. This study also increases the relevance of Cohenls art-+$. explkca- -----1 ' ting -the m-my .themes that relate to the struggle of modern , man in a violent and dehumanizing society. r'\ \ /--'-- ./' ../" ->I \ The for s _wo_rld.aiew-b'eginsin Let Us /' ----- -'I \Compare Flytholoqies wy&f his inn-Raps naive --.-- ----.. - - -- gies upon which man bases7 his -> osophies. TGSconclusion i /' /' Cohen.. stioning is initially an acceptance of the "elaborate lieu that rationalizes the violence of life and death. There is, however, the growing desire on the poet's part to escape this violence. -

Proquest Dissertations

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY He'll: Parody in the Canadian Poetic Novel by Nathan Russel Dueck A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH CALGARY, ALBERTA NOVEMBER, 2009 © Nathan Russel Dueck 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-64097-5 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-64097-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

“Who Is the Lord of the World?” Leonard Cohen’S Beautiful Losers and the Total Vision

Medrie Purdham “Who is the Lord of the World?” Leonard Cohen’s Beautiful Losers and the Total Vision Here is my big book. I hope you don’t think it’s too big. I want it to be the very opposite of a slim volume. I hope I’ve made some contribution to the study of the totalitarian spirit and I needed a lot of space and forms to make my try. —Leonard Cohen, in a letter to Miss Claire Pratt of McClelland & Stewart about Flowers for Hitler, 19641 When Leonard Cohen wrote to his publisher in 1964 about the size of his book of poetry, Flowers for Hitler, he described an almost inevitable formal identification of the “big book” with its subject, “the totalitarian spirit.” With customary humility, Cohen suggests that the work is big not because it is authoritative but rather because it is tentative. An artist must be an uneasy kind of world-maker and certainly an uneasy kind of experimentalist where his writing engages totalitarian themes. Totalitarianism itself has often been explored for its analogy to art; Walter Benjamin viewed totalitarianism as the aestheticization of politics2 and Hannah Arendt explored, similarly, its perverse idealism.3 Further, Arendt’s influential critique of totalitarianism, which I will draw on centrally, emphasizes its essential unworldliness and foregrounds its novelty, dubbing it “a novel form of government” (Origins 593). An unworldly creativity animates Cohen’s Beautiful Losers (1966), a book that is bigger and more wildly inclusive than its predecessor. This novel touches on totalitarian themes, themes that readers might find uncomfortably reflected in Cohen’s own apparent search for a total vision. -

Leonard Cohen's Experimental 1966 Novel, Beautiful Losers, Is His

Benadé 1 Systems and Self: Understanding the Posthuman in Beautiful Losers Richard Benadé English 499 November 16, 2009 Benadé 2 Leonard Cohen‟s experimental 1966 novel, Beautiful Losers, is his second foray into the novel form. Cohen uses the text to balance his conflicting views of technology as neither the great liberator of humanity nor the bane of that which signals human identity. The human condition arises shakily from the dialectic formed between these two extremes. Cohen demonstrates that Western society has entered an age whereupon it relies on technology to a dangerous degree. The reliance humans have upon technology endangers identity, yet through this obsessive relationship, humans may find a means of transcendence. Katherine Hayles‟ book, How We Became Posthuman, similarly addresses the implications of the changing relationship between human beings and machines. The novel yields well to posthuman analysis for two reasons: On the level of content the text‟s references to technology and media are highly suggestive of the concerns to be found within posthuman discourse. Perhaps of greater interest, is the means by which the text, as a form, reflects the concepts posited by posthuman theorists. Cohen shows, with both anxiety and desire, the West‟s transformation into a posthuman society. While posthumanism endangers identity at the level of content—producing an identity crisis for the characters of the text—Beautiful Losers ultimately relies on the posthuman discourse that it anticipates in order to inform its structure. The novel centres on the spiral into madness that the nameless protagonist (conventionally named “I” in literary criticism) undergoes as he tries desperately to cling to a sense of individuality. -

Leonard Cohen's New Jews: a Consideration of Western Mysticisms in Beautiful Losers Alexander Lombardo Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2017 Leonard Cohen's New Jews: a Consideration of Western Mysticisms in Beautiful Losers Alexander Lombardo Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Lombardo, Alexander, "Leonard Cohen's New Jews: a Consideration of Western Mysticisms in Beautiful Losers" (2017). CMC Senior Theses. 1539. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1539 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College Leonard Cohen’s New Jews: a consideration of Western mysticisms in Beautiful Losers submitted to Professor Robert Faggen and Dean Peter Uvin by Alex Lombardo for Senior Thesis 2016-2017 24 April 2017 Lombardo 2 Lombardo 3 Abstract This study examines the influence of various Western mystical traditions on Leonard Cohen’s second novel, Beautiful Losers. It begins with a discussion of Cohen’s public remarks concerning religion and mysticism followed by an assessment of twentieth century Canadian criticism on Beautiful Losers. Three thematic chapters comprise the majority of the study, each concerning a different mystical tradition—Kabbalism, Gnosticism, and Christian mysticism, respectively. The author considers Beautiful Losers in relation to these systems, concluding that the novel effectively depicts the pursuit of God, or knowledge, through mystic practice and doctrine. This study will interest scholars seeking a careful exploration of Cohen’s use of religious themes in his work. Lombardo 4 This thesis is dedicated to the memory of Leonard Norman Cohen. Lombardo 5 Table of Contents 1. -

Leonard Cohen: a Crack in Everything the Jewish Museum April 12 – September 8, 2019

Leonard Cohen: A Crack in Everything The Jewish Museum April 12 – September 8, 2019 Exhibition Wall Texts LEONARD COHEN: MOMENTS COMPILED BY CHANTAL RINGUET Topos_JM_LC_WallTexts_24p.indd 1 4/4/19 12:34 PM SEPTEMBER 21, 1934 BIRTH OF LEONARD NORMAN COHEN IN WESTMOUNT Born into a Westmount Jewish family that was part of Montreal’s Anglo elite, Leonard Norman Cohen was the second child of Masha Klinitsky- Klein and Nathan Bernard Cohen. Lyon Cohen, Leonard’s paternal grandfather, a well- known businessman and philanthropist, was an important figure in the Jewish community. He started the Freedman Company, one of the largest clothing manufacturers in Montreal, and cofounded the Canadian Jewish Times (1897), the first English- language Jewish newspaper in Canada. Lyon Cohen was also president of several organizations, including the Canadian Jewish Congress and Congregation Shaar Hashomayim. He helped Jewish immigrants from the Russian Empire settle in Canada—among them, from Lithuania, the learned Rabbi Solomon Klinitsky- Klein and his family. Lyon’s son, Nathan Cohen, a lieutenant in the Canadian army and World War I veteran, later ran the family business. From his father, the young Leonard inherited a love of suits; from his mother, Masha, who trained as a nurse, he received his charisma and his love of songs. Cohen’s well- to- do family was quite different from the Jewish masses who arrived in Montreal in the early twentieth century. Many of these immigrants spoke Yiddish as their native language and worked in garment factories. Despite his extensive travels and his residence in Los Angeles, Cohen always returned to Montreal to “renew his neurotic affiliations,” as he often repeated in interviews. -

The Favorite Game 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE FAVORITE GAME 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Cohen | 9781400033621 | | | | | The Favorite Game 1st edition PDF Book Feb 03, Stacy LeVine rated it really liked it. Brotherhood is still my favorite of the series. Breavman isn't as interesting a character to me as one of his lady friends, Shell. It wasn't just that the forms were perfect, or that he knew them so well. I tried to record my favourite lines but there was nearly one on every page. Cohen is a master of subtlety, I was most impressed with his description of a masturbation session chapter 19 , without once mentioning the word masturbation or anything blatantly related to it. This game is truly fantastic. Along with all of that, there was the great multiplayer. What will the favorite game turn out to be? Shell Cary Lawrence I still remember how my jaw hit the floor with the game's ending. We do not guarantee that these techniques will work for you. Shadow of Mordor is truly the first next-gen game and will no doubt inspire developers to adopt this revolutionary system. So i can tell only for scenario Jan 15, Kathy rated it really liked it. Looking for something to watch? Sign In Don't have an account? Incest films. Cohen acknowledges that this solipsism affects those around Breavman, but the character keeps falling back into it, unable to break the cycle of thinking he's had since he was a child. In the sheer genius of his style, Cohen redeems his protagonist from his life of arrogance an This book is the reason why I give less than five stars to so many others. -

Mad Translation in Leonard Cohen's Beautiful Losers and Douglas

Mad Translation in Leonard Cohen’s Beautiful Losers and Douglas Glover’s Elle Robert David Stacey University of Ottawa The lunatic, the lover and the poet. Are of imagination all compact. William Shakespeare his essay discusses Leonard Cohen’s Beautiful Losers and Doug- Tlas Glover’s Elle, two postmodern Canadian novels whose subversions and parodies of conventional realism, still the dominant mode of histori- cal fiction in Canada and elsewhere, are intimately connected with their exploration of the foundations and limits of modern historical conscious- ness. More specifically, my argument arises out of what I perceive to be some crucial similarities between the two texts. Both address the early stages of the European colonization of North America and the concomi- tant mutual exposure to the other of radically alien cosmologies: one oral, polytheistic, and tribal; the other literate, monotheistic, and nationalist. Both feature protagonists whose attempts to understand this otherness in its own terms—or to inhabit the reality of the other—leads to a radical destabilization of personal and cultural identity, resulting in a state akin to ESC 40.2–3 (June/September 2014): 173–197 divine madness, an ecstatic breakthrough that is nevertheless profoundly isolating and destructive for the individual subject. Crucially, both novels approach this paradox of breakdown and break- Robert David Stacey through in terms of translation, which functions as a master trope for any is Associate Professor manner of inter-experiential relations that have a transformative effect on of Canadian Literature the subject and his or her way of being-in-the-world. Indeed, it is precisely at the University of at the point where translation in the ordinary sense, derived from the Latin Ottawa. -

Leonard Cohen I

Leonard Cohen I BYAMTHOKY D e CURTIS always experience myself as falling apart, been assured by this one-alone. However, the two and I’m taking emergency measures,” Leon- extraordinary albums that followed, Songs From a ard Cohen said fifteen years ago. “It’s coming Room (1969), which includes his classic song “Bird on apart at every moment. I try Prozac. I try love. a W ire,” and Songs of Love and Hate (1971), provided I try drugs. I try Zen meditation. I try the whatever proof anyone may have required that the monastery.I I try forgetting about all those strategies greatness of his debut was not a fluke. and going straight. And the place where the evaluation Part of the reason why Cohen’s early work revealed happens is where I write the songs, such a high degree of achieve when I get to that place where I For four decades, ment is that he was an accom can’t be dishonest about what I’ve plished literary figure before he been doing.” Cohen has been a m odel ever began to record. His collec For four decades, Cohen has ofgut'wrenching tions of poetry, including Let Us been a model of gut-wrenching emotional honesty Compare Mythologies (1956) and emotional honesty. He is, with Flowers for Hitler (1964), and his out question, one of the most novels, including Beautiful Losers important and influential songwriters of our time, (1966), had already brought him considerable recogni a figure whose body of work achieves greater depths tion in his native Canada. -

Beatrice Wolfe Watson 1 the Strange Case of Leonard Cohen

Beatrice Wolfe Watson 1 The Strange Case of Leonard Cohen: ‘There is a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.’1 Leonard Cohen has been a published and critically regarded poet for over fifty years, and a prolific recorded songwriter for over forty years (ca twelve poetry collections and sixteen albums). Despite his multifarious artistic endeavours, he has remained either a contentious figure for critical consideration or a neglected one. Cohen has continually evaded clear-cut classification by not fitting easily ‘into the categories of post-modern or the post-colonial; his obstinate Romanticism is seen as reactionary; and his treatment of women has been…an outright offence to feminist critics.’2 In the figure of Leonard Cohen, we see an artist remake his role and redirect the scope of his influence to the point of exhaustion, if not oblivion; an introspective artist who is at war with himself, with his work, and with the collective tradition he remains attached to, if only by an invisible thread. Cohen’s self-effacing attitude towards himself as a writer was unlikely to inspire the confidence of his most devoted critics, especially when he replaced his poetry collections with albums, triggering anxieties of popularism and material preciousness in relation to poetic art. However, Cohen’s willingness to take real risks with his work, even at the expense of falling into cliché, bathos, banality, and critical obscurity, has paid off on countless occasions and resulted in the poet-songwriter achieving artistic longevity through his great power to move, and stir the very soul of the reader or listener.