Financial Accessibility of the Street Vendors in India: Cases of Inclusion and Exclusion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uniform Municipal Accounting

Re-Development of 26,516 Sqm. Railway Staff Colony land , at Guwahati Railway Station Pre-Bid Meeting Presentation 30.08.2019 & 03.09.2019 About RLDA ▸ Railway Act 1989 amended in 2005 to establish RLDA – a Statutory Authority under Ministry of Railways for Commercial Development of vacant railway land for generating revenue (required by Railways for up-gradation/maintenance of its network) by non-tariff measures. This amendment essentially contains the following provisions: ▸ RLDA became functional on 19th Jan 2007 after notification of RLDA (Constitution) Rules, 2007 ▸ Railway Act 1989, Chapter (IIA), Article 4D states function of the Authority as follows: ▸ Shall discharge such functions and exercise such power of central government in relation to development of railway land, for commercial use, assigned by the central government; ▸ Has power to enter into agreement and execute contract for the above. ▸ Section 11 of the Railways Act, which empowers the railway administrations to execute various works required for the purposes of constructing and maintaining a railway has also been amended to include, vide sub-clause (da), “developing any railway land for commercial use”. Re- Development of 26,512 Sqm. Railway Staff Colony Land , at Guwahati Railway Station Privileged & Confidential Page 1 ADROIT - RSP ADVISORS 06-09-2019 About ADROIT & CO and RSP Advisors (Financial & Marketing Consultants) # Area of Experience Years / Value of the ADROIT & CO and RSP Advisors (Consortium) No. of Project(s) Financial & Marketing Consultants Projects (Rs. In Crores) Raj Kumar Dua, ADROIT & CO, Chartered Accountants, New Delhi (33 years, Since 1986) (Valuation, Financial Modelling, Transaction Advisory, Marketing and Financial Close of Projects on PPP Mode) 1 Real Estate Sector: Since 2003 Since 2003 Approx. -

Hawkers' Movement in Kolkata, 1975-2007

NOTES hawkers’ cause. More than 32 street-based Hawkers’ Movement hawker unions, with an affiliation to the mainstream political parties other than the in Kolkata, 1975-2007 ruling Communist Party of India (Marxist), better known as CPI(M), constitute the body of the HSC. The CPI(M)’s labour wing, Centre Ritajyoti Bandyopadhyay of Indian Trade Unions (CITU), has a hawk- er branch called “Calcutta Street Hawkers’ In Kolkata, pavement hawking is n recent years, the issue of hawkers Union” that remains outside the HSC. The an everyday phenomenon and (street vendors) occupying public space present paper seeks to document the hawk- hawkers represent one of the Iof the pavements, which should “right- ers’ movement in Kolkata and also the evo- fully” belong to pedestrians alone, has lution of the mechanics of management of largest, more organised and more invited much controversy. The practice the pavement hawking on a political ter- militant sectors in the informal of hawking attracts critical scholarship rain in the city in the last three decades, economy. This note documents because it stands at the intersection of with special reference to the activities of the hawkers’ movement in the city several big questions concerning urban the HSC. The paper is based on the author’s governance, government co-option and archival and field research on this subject. and reflects on the everyday forms of resistance (Cross 1998), property nature of governance. and law (Chatterjee 2004), rights and the Operation Hawker, 1975 very notion of public space (Bandyopadhyay In 1975, the representatives of Calcutta 2007), mass political activism in the context M unicipal Corporation (henceforth corpora- of electoral democracy (Chatterjee 2004), tion), Calcutta Metropolitan Development survival strategies of the urban poor in the Authority (CMDA), and the public works context of neoliberal reforms (Bayat 2000), d epartment (PWD) jointly took a “decision” and so forth. -

ASSAM ELECTRICITY GRID CORPORATION LIMITED Bidding

ASSAM ELECTRICITY GRID CORPORATION LIMITED Regd. Office: 1st Floor, Bijulee Bhawan, Paltan Bazar, Guwahati – 781001 CIN: U40101AS2003SGC007238 Ph:- 0361-2739520/Fax:-0361-2739513 Web: www.aegcl.co.in Bidding Document For Construction of boundary wall including gate in front of proposed Control and Communication Centre at AEGCL Campus, Kahilipara. Terms, conditions and technical specifications of contract with item rate schedule NIT No. : AEGCL/DGM/LAC/TT/2016/239 Dated : 29-12-2016 Issued to: Name: ............................................................................................................................. Address: .............................................................................................................................. Tender will be received upto 14:00 hours (IST) of 19-01-2017 Deputy General Manager Lower Assam T&T Circle, AEGCL Narengi, Guwahati-26 ASSAM ELECTRICITY GRID CORPORATION LIMITED To, The Deputy General Manager, Lower Assam T&T Circle, AEGCL, Narengi, Guwahati-26 Sub: - Submission of Tender Paper. Name of work: - Construction of boundary wall including gate in front of proposed Control and Communication Centre at AEGCL Campus, Kahilipara. Ref: - Your Tender Notice No. .………………………………………………………………………………… Sir, With reference to the above NIT and the work, I hereby offer to execute the work at following rate i) % above ii) % below iii) At per schedule of rates for building of APWD for the year 2013-14 Requisite amount of Earnest money amounting to Rs………………………….. (……………………………………………………….. ) only -

Public Health Research Series

UNIVERSITY Public Health Research Series 2012 Vol.1, Issue 1 School of Public Health I Preface “A scientist writes not because he wants to say something, but because he has something to say” – F. Scott Fitzgerald The above quote more or less summarizes the essence of this publication. The School of Public Health, SRM University takes great pride and honor in bringing out the first of its Public Health Research Series, a compilation of research papers by the bright and intelligent students of the school. The Series has come out to provide a platfrom for sharing of research work by students and faculty in the field of publuc health. The studies reported in this Series are small pilot projects with scope for scaling up in larger scale to address important public health issues in India. They come from diverse settings spanning the length and breadth of the country, neighboring countries like Nepal and Bhutan, diverse linguistic, cultural and socio economic backgrounds. Some of the projects have generated important hypothesis for further testing, some have done qualitative exploration of interesting concepts and yet others have tried to quantify certain constructs in public health. This book is organized into a set of 25 full reports and 5 briefs. The full reports give an elaborate description of the study objectives, methods and findings with interpretations and discussions of the authors. The briefs are unstructured concept abstracts. The studies were done by the students of the school of public health as their term project under the guidance of the faculty mentors to whom they were assigned at the time of enrolment into the course. -

Population Growth and Forest Degradation in Guwahati City: a GIS Based Approach I.Introduction

International Journal of Interdisciplinary Research in Science Society and Culture(IJIRSSC) Vol: 1, No.:1, 2015 ISSN 2395-4335, © IJIRSSC www. ijirssc.in ________________________________-________________ Population Growth and Forest Degradation in Guwahati City: A GIS Based Approach 1 Rinku Manta , 2 Dhrubajyoti Rajbangshi 1Research Scholar, Geography Department, Gauhati University, Assam ,India 2Assistant Professor, Guwahati College, Guwahati-21, Assam, India ___________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT : Being the prime city in the north eastern part of India, the pressure of population growth in the Guwahati city is very high compared to other cities of developing nations. In last few decades, due to ever increasing anthropogenic activities, the city is facing many geo-ecological problems. Naturally the physiographic conditions have cumulative effect on the growth and distribution of population and settlement pattern. This city has been characterized by a complex pattern of human habitation of as many as 809,895 populations within 216 sq. km. geographical area in 2001. The physiography of the area is not plain one and 20 numbers of small and big hillocks are found covered with forest which has great impact on keeping the city pollution free environment with healthy ecological balance. Among these hillocks 9 are identified as a reserve forest. Due to population pressure large number of encroachment and deforestation has been seen, resulting squeezes the area of the hillocks. The study is based on primary and secondary data collected from different sources. The collected data are analyzed through GIS software to find the output explicitly. Therefore, an attempt has been made in this paper to analyze the population pressure, changing forest dynamics and its related phenomena and encroachment pattern in the study area. -

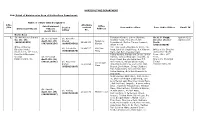

Detail of Division Wise Area of Horticulture Department. S.No. /Div. Name of Officer with Designati

HORTICULTURE DEPARTMENT Sub: Detail of division wise Area of Horticulture Department. Name of Officer with Designation S.No. Alternate Sub-Divisional Office /Div. Section contact Area under officer Zone Under Officer Email. Id Divisional Officers Officers Address Officer No. (Asstt. Dir.) North Zone 1. Sh. Anil Kumar Sharma Talkatora Garden, Indoor Stadium, Sh. K. P. Singh, kpsingh0202 Sh. Neeraj Kant Sh. Ravinder Dy. Dir. (H) Shankar Road, Park Street, RML Director (Hort.)- @gmail.com Asstt. Dir. (H) Kharab Talkatora (9899591033) 23092033 Roundabout, Mother Teresa Crescent, North (9871854254) (9868538501) Garden Urban Forest (9891220990) Office of the Dy. DIZ-I surrounded by Mandir Marg, P.K. Sh. Lokesh Kr. 23348127 Kali Bari Director (Hort.) Road, Bhai Vir Singh Marg, R.K.Ashram Office of the Director (9868030878) Marg Room 1306, 13th Floor, Marg, Kali Bari, Peshwa Road. Horticulture-North New Delhi Municipal Palika Kendra, Parliament Street, Jantar Room 1304, 13th Council Sh. K.P.Singh Mantar, Tolstoy Marg upto Janpath, Jai Floor, Palika Kendra, ND Asstt. Dir. (H) Singh Road, Bangla Sahib Park,T.T. New Delhi Municipal (9911115371) Sh. Kapender Park Nursery, Bangla Shaib Road, Council Connaught Kumar 23323294 Hanuman Road area, Sector-IV, DIZ, Palika Kendra, ND Place (9350131687) Bhagat Singh Marg, Shivaji Stadium, Man Singh Road, Palika Bazaar and Palika Parking, Gole Dak Khana & its segments. North Avenue, BKS Marg, DIZ, Sector- IV, Shaheed Bhagat Singh Marg, upto Gole Market upto Bhai Veer Singh Marg, , Ashoka Road, Janpath, & surrounding area, , Rajender Prasad Road, Windsor Place, Riasina Road, R/A Krishi Bhavan, Sh. Rais Ali, Sh. Pankaj Pt.Pant Statue, Pt.Pant Marg, Asstt. -

44508-001: Strengthening Urban Transport Subsector Under ADB

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Technical Assistance 7750-IND September 2013 India: Strengthening Urban Transport Subsector under ADB-supported Urban Development Projects − Urban Transport Component Prepared by Gordon Neilson, Subhajit Lahiri and Prasant Sahu, Study Team Members For the Ministry of Urban Development This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. ASSAM URBAN INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECT URBAN TRANSPORT COMPONENT ADB Contract S71818 TA- 7750(IND) FINAL REPORT October 2011 Contract S71818; TA – 7750 (IND) Final Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Objectives of Study and Tasks .................................................................................. 1 1.3 Organisation of Report .............................................................................................. 2 2. PUBLIC TRANSPORT SECTOR ASSESSMENT ..................................................... 3 2.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Current Situation ....................................................................................................... 4 2.3 Road Map for the Future .......................................................................................... -

Full Name of the Faculty Member: DR PURBA CHATTOPADHYAY De

UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA DEPARTMENTAL ACADEMIC PROFILE FACULTY PROFILE: Full name of the faculty member: DR PURBA CHATTOPADHYAY Designation: ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR Specialization: ECONOMETRICS AND STATISTICS Contact information: Department of Home Science, University of Calcutta, 20B, Judges Court Road, Kolkata 7000027, West Bengal, India Email: [email protected] ; [email protected] Phone no: +91-9433739418 1 of 11 Dr Purba Chattopadhyay Academic Qualifications: College/ University from which Degree Abbreviation of the degree was obtained Rabindra Bharati University BA (Economics) Rabindra Bharati University MA in Economics (specialization in Econometrics and statistics) Jadavpur University PhD UGC NET Qualified Substantive Position(s) held/holding: Assistant Professor (Economics) at Gobardanga Hindu College (2003-2013) Assistant Professor (Economics with Statistics) Department of Home Science (2013-Contd) Research interests: Household Food Security. Human Development Indices. Community Nutrition. Gender and Exclusion. Extension Education. Sustainable Development. Research Methodology & Statistical Application. Research guidance: Registered for Ph.D. - 01 candidate (joint supervisor with Professor Paromita Ghosh) in Human Development, Home Science. 01 enrolled in Human Development, Home Science. Projects: • UGC Sponsored Minor Research Project, 2011, Amount: INR 1,11,500/- Title: “A Study on Vending on Railways by Hawkers in Kolkata, West Bengal, UGC Order No. F.PHW-120/10-11 (ERO), dated 21.10.10 • UGC-UPE Major Research Project, 2018, Amount INR15, 00,000/- Title: “Adolescent mental Health: Prevalence of different Types of Problems and their Interventions”, Ref No: DPO/369/UPE II/Non Focs, dated 2.11.2018, Co-P.I • THE ASIATIC SOCIETY, Reproductive Health behaviour of women: A comparative Study Among the tribes of North East and Central India. -

Bazaars and Video Games in India

Bazaars and Video Games in India Maitrayee Deka Abstract This article examines the history of video games in India through the lens of Delhi’s electronic bazaars. As many gamers shifted from playing Atari Games in the 1980s to PlayStation in the 2000s, we see a change in the role that the bazaars play. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the bazaars were the crucial channels of smuggling video games into India. In the 2000s, the bazaars face competition from official channels. Increasingly, the branded showrooms and online market attract elite consumers who can afford to buy the latest original video game. I argue that, while in the twenty-first century, the electronic bazaars have seen a decline in their former clientele, they now play a new role: they have become open places through the circulation of “obsolete” video games, and the presence of a certain bazaari disposition of the traders. The obsolete games in the form of cartridge, cracked console, and second hand games connect video games to people outside the elite network of corporate and professional new middle class. This alongside the practice of bargaining for settling price creates dense social relationships between a trader and a consumer. Keywords India, video games, bazaars, obsolescence, openness, innovation Introduction The popularity of video games has been elusive in India. Video games appearing as a leisure time activity and the possibility to play a quick game on smartphones add to their casual nature. Even though there are fewer glorifications of video games either as a profession or as a mode of military training, the outreach of video games in the country cannot be ignored. -

The Public Body: Individual Tactics and Activist Interventions on The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Texas A&M Repository THE PUBLIC BODY: INDIVIDUAL TACTICS AND ACTIVIST INTERVENTIONS ON THE STREET IN DELHI, INDIA A Thesis by BRIDGET CONLON LIDDELL Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Chair of Committee, Kirsten Pullen Committee Members, Jayson Beaster-Jones Rumya Putcha Jyotsna Vaid Head of Department, Donnalee Dox August 2015 Major Subject: Performance Studies Copyright 2015 Bridget Conlon Liddell ABSTRACT After a brutal and widely publicized gang rape in December 2012, women’s safety in public spaces has been a significant site of debate and discourse about Delhi as a city and India as a country. My Master’s thesis focuses on women’s negotiations of public spaces in Delhi, India. I explore how women in general—and activists in particular—shift Delhi’s public culture, in order to intervene in dominant discourses on women’s agency in India’s capital as well as the dismissive, alienating narratives of the city as hopelessly violent. Jagori, a Delhi-based women’s rights organization, sponsors “The Safe Delhi Campaign” to address the constraints on and challenges of women’s Delhi street experience with a focus on urban design, public transport, and raising public awareness. My project brings a Performance Studies perspective to Jagori’s goals, paying close attention to my interlocutors’ (university-aged female residents and Jagori activists) voices, bodies, and tactics. -

National Social Work Perspective - 2017

National Social Work Perspective - 2017 INTRODUCTION Social work students, shift 1, from Loyola College undertook a study tour to New Delhi for ten days. They were exposed to various educational institutions, industries, national and international organizations. The students, also, had an opportunity to visit Jaipur and Agra. Through this study tour they gained lot of experience in various aspects. The students were also exposed to new environment and acquired some knowledge about the cultural aspects and also a vast exposure to the discipline of social work. Hence the study tour was a successful one which enabled the students to gain full pledged knowledge about their own field or specialization OBJECTIVES To provide an opportunity to the students to experience group dynamics and understand the importance of social relationships To be aware of various socio-cultural patterns, value system and social practice in different parts of the world. To visit various reputed organizations related to their field of specialization and understand and functioning of such successful organizations. To build in competencies related to planning, implementation and execution of tasks related to the organizing group travel and accommodation and visit etc. To impart training in social work education through purposeful recreation, sightseeing and discussion in different places and atmosphere. PRE-TOUR ACTIVITIES SELECTION OF LEADERS The professors Dr. Gladston Xavier and Dr. Akileswari who were in charge of the study tour guided the selection of the study tour leaders. Mr. Felix and Miss. Elma were unanimously elected as study tour leaders. The professors guided the students to form various committees. A series of regular meeting were held to plan out various aspects of the study tour. -

District New Delhi

District New Delhi The mega mock drill conducted on 15 .02.12 has raised awareness that when earthquake strikes it would be required that both citizens and authorities are working in unison to minimise the damage. The drill was carried out at following locations in New Delhi District:- 1) Sanjay Camp, Chanakya Puri 2) B R Camp, Race Course 3) Janta Camp, Near Pragati Maidan 4) Lok Nayak Bhawan, Khan Market 5) Khan Market Metro Station 6) Yashwant Place, 7) Housing Complex Kali Bari Marg 8) Mohan Singh Place 9) Doordarshan Bhawan 10) Palika Bazaar Following Departments participated in this mega exercise organized in New Delhi District on 15 th February, 2012 in all the incident sites: - 1. Civil Defence Volunteers 2. Delhi Police 3. PCR 4. Traffic Police 5. CATS and SJAB 6. NDMC (Civil) 7. NDMC (Fire) 8. DTC 69 9. NDMC (Water Supply) 10. Delhi Fire Services 11. Food and Supply Dept 12. NDMC (Education) 13. NDMC (Electricity) 14. BSES 15. MCD 16. MTNL 17. NDRF Two relief centres were identified and made operational during the drill. They are as under:- S. No. Name of Relief Centre Location of Evacuees a) 100 shifted from Sanjay NP Middle School, Dharam Marg, Kitchner Camp, Chankya Puri. 1. Road, New Delhi b) 50 shifted from B. R. Camp, Race Course. 2. NP Bengali Girls Senior Sec. School, Gole a) 20 shifted from Janta Market, New Delhi Camp, Pragati Maidan. b) 30 shifted from Housing Complex, Kalibari Marg. Total No. of Dead : 10 Total No. of Major Injury : 36 Total No.