The Public Body: Individual Tactics and Activist Interventions on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

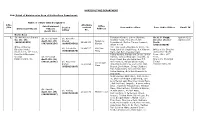

Detail of Division Wise Area of Horticulture Department. S.No. /Div. Name of Officer with Designati

HORTICULTURE DEPARTMENT Sub: Detail of division wise Area of Horticulture Department. Name of Officer with Designation S.No. Alternate Sub-Divisional Office /Div. Section contact Area under officer Zone Under Officer Email. Id Divisional Officers Officers Address Officer No. (Asstt. Dir.) North Zone 1. Sh. Anil Kumar Sharma Talkatora Garden, Indoor Stadium, Sh. K. P. Singh, kpsingh0202 Sh. Neeraj Kant Sh. Ravinder Dy. Dir. (H) Shankar Road, Park Street, RML Director (Hort.)- @gmail.com Asstt. Dir. (H) Kharab Talkatora (9899591033) 23092033 Roundabout, Mother Teresa Crescent, North (9871854254) (9868538501) Garden Urban Forest (9891220990) Office of the Dy. DIZ-I surrounded by Mandir Marg, P.K. Sh. Lokesh Kr. 23348127 Kali Bari Director (Hort.) Road, Bhai Vir Singh Marg, R.K.Ashram Office of the Director (9868030878) Marg Room 1306, 13th Floor, Marg, Kali Bari, Peshwa Road. Horticulture-North New Delhi Municipal Palika Kendra, Parliament Street, Jantar Room 1304, 13th Council Sh. K.P.Singh Mantar, Tolstoy Marg upto Janpath, Jai Floor, Palika Kendra, ND Asstt. Dir. (H) Singh Road, Bangla Sahib Park,T.T. New Delhi Municipal (9911115371) Sh. Kapender Park Nursery, Bangla Shaib Road, Council Connaught Kumar 23323294 Hanuman Road area, Sector-IV, DIZ, Palika Kendra, ND Place (9350131687) Bhagat Singh Marg, Shivaji Stadium, Man Singh Road, Palika Bazaar and Palika Parking, Gole Dak Khana & its segments. North Avenue, BKS Marg, DIZ, Sector- IV, Shaheed Bhagat Singh Marg, upto Gole Market upto Bhai Veer Singh Marg, , Ashoka Road, Janpath, & surrounding area, , Rajender Prasad Road, Windsor Place, Riasina Road, R/A Krishi Bhavan, Sh. Rais Ali, Sh. Pankaj Pt.Pant Statue, Pt.Pant Marg, Asstt. -

Bazaars and Video Games in India

Bazaars and Video Games in India Maitrayee Deka Abstract This article examines the history of video games in India through the lens of Delhi’s electronic bazaars. As many gamers shifted from playing Atari Games in the 1980s to PlayStation in the 2000s, we see a change in the role that the bazaars play. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the bazaars were the crucial channels of smuggling video games into India. In the 2000s, the bazaars face competition from official channels. Increasingly, the branded showrooms and online market attract elite consumers who can afford to buy the latest original video game. I argue that, while in the twenty-first century, the electronic bazaars have seen a decline in their former clientele, they now play a new role: they have become open places through the circulation of “obsolete” video games, and the presence of a certain bazaari disposition of the traders. The obsolete games in the form of cartridge, cracked console, and second hand games connect video games to people outside the elite network of corporate and professional new middle class. This alongside the practice of bargaining for settling price creates dense social relationships between a trader and a consumer. Keywords India, video games, bazaars, obsolescence, openness, innovation Introduction The popularity of video games has been elusive in India. Video games appearing as a leisure time activity and the possibility to play a quick game on smartphones add to their casual nature. Even though there are fewer glorifications of video games either as a profession or as a mode of military training, the outreach of video games in the country cannot be ignored. -

National Social Work Perspective - 2017

National Social Work Perspective - 2017 INTRODUCTION Social work students, shift 1, from Loyola College undertook a study tour to New Delhi for ten days. They were exposed to various educational institutions, industries, national and international organizations. The students, also, had an opportunity to visit Jaipur and Agra. Through this study tour they gained lot of experience in various aspects. The students were also exposed to new environment and acquired some knowledge about the cultural aspects and also a vast exposure to the discipline of social work. Hence the study tour was a successful one which enabled the students to gain full pledged knowledge about their own field or specialization OBJECTIVES To provide an opportunity to the students to experience group dynamics and understand the importance of social relationships To be aware of various socio-cultural patterns, value system and social practice in different parts of the world. To visit various reputed organizations related to their field of specialization and understand and functioning of such successful organizations. To build in competencies related to planning, implementation and execution of tasks related to the organizing group travel and accommodation and visit etc. To impart training in social work education through purposeful recreation, sightseeing and discussion in different places and atmosphere. PRE-TOUR ACTIVITIES SELECTION OF LEADERS The professors Dr. Gladston Xavier and Dr. Akileswari who were in charge of the study tour guided the selection of the study tour leaders. Mr. Felix and Miss. Elma were unanimously elected as study tour leaders. The professors guided the students to form various committees. A series of regular meeting were held to plan out various aspects of the study tour. -

District New Delhi

District New Delhi The mega mock drill conducted on 15 .02.12 has raised awareness that when earthquake strikes it would be required that both citizens and authorities are working in unison to minimise the damage. The drill was carried out at following locations in New Delhi District:- 1) Sanjay Camp, Chanakya Puri 2) B R Camp, Race Course 3) Janta Camp, Near Pragati Maidan 4) Lok Nayak Bhawan, Khan Market 5) Khan Market Metro Station 6) Yashwant Place, 7) Housing Complex Kali Bari Marg 8) Mohan Singh Place 9) Doordarshan Bhawan 10) Palika Bazaar Following Departments participated in this mega exercise organized in New Delhi District on 15 th February, 2012 in all the incident sites: - 1. Civil Defence Volunteers 2. Delhi Police 3. PCR 4. Traffic Police 5. CATS and SJAB 6. NDMC (Civil) 7. NDMC (Fire) 8. DTC 69 9. NDMC (Water Supply) 10. Delhi Fire Services 11. Food and Supply Dept 12. NDMC (Education) 13. NDMC (Electricity) 14. BSES 15. MCD 16. MTNL 17. NDRF Two relief centres were identified and made operational during the drill. They are as under:- S. No. Name of Relief Centre Location of Evacuees a) 100 shifted from Sanjay NP Middle School, Dharam Marg, Kitchner Camp, Chankya Puri. 1. Road, New Delhi b) 50 shifted from B. R. Camp, Race Course. 2. NP Bengali Girls Senior Sec. School, Gole a) 20 shifted from Janta Market, New Delhi Camp, Pragati Maidan. b) 30 shifted from Housing Complex, Kalibari Marg. Total No. of Dead : 10 Total No. of Major Injury : 36 Total No. -

Vasudha Mehta Volunteers Manager, Delhi Greens 48°C Public·Art

Feedback: Vasudha Mehta 48c Volunteers Manager, Delhi Greens Public 48°C Public·Art·Ecology Festival Art Ecology 48°C Public·Art·Ecology Festival for me was all about communicating ecological messages to the masses and sensitizing them towards the perils of damages that have been inflicted upon our fragile ecology. The Festival required a Volunteer Team that was able to communicate and interpret the ecological messages of individual Art Installation to the general public. The task of finding suitable volunteers was a challenging experience. The search for volunteers began by making visits to the various colleges in Delhi, interacting with their Eco-Clubs and Environmental Society representatives and making the Call for Volunteer well in advance. The bulk of the applications started pouring as the month of December started and by the time the festival started we had volunteer representation from many colleges, including Hansraj, IP College for Women, Hindu College, Daulat Ram College, Khalsa College, School of Environmental Studies, Department of Anthropology, Miranda House, Kirori Mal College, St. Stephens College and also from JNU, Jamia University, College of Art and TVB School of Habitat Studies. Once the Festival started, it was yet another challenge to keep the volunteers enthused and motivated as the first day caught us all by surprise. Few sites were not installed in time and a few were far different from what we had imagined. Each volunteer was provided a Feedback Register, for citizens to share their experience and understanding -

Counterfeit Luxury Brands Scenario in India: an Empirical Review

International Journal of Sales & Marketing Management Research and Development (IJSMMRD) ISSN(P): 2249-6939; ISSN(E): 2249-8044 Vol. 4, Issue 2, Apr 2014, 1-8 © TJPRC Pvt. Ltd. COUNTERFEIT LUXURY BRANDS SCENARIO IN INDIA: AN EMPIRICAL REVIEW SUVARNA PATIL1 & ARUN HANDA2 1Marketing, Sinhgad Intitute of Management and Computer Application, Pune, Maharashtra, India 2Ph.D. Guide, Nagpur University, Nagpur, Maharashtra, India ABSTRACT Counterfeiting is considered as a serious threat to the global economy. Counterfeit goods not only cause loss to the nation but also affects the employment growth by closing down small and medium industries. Right from handbags, jewelry and shoes to brake pads, electric cords, and pharmaceuticals and health care supplies, counterfeiters leave no product category untouched. This paper gives an overview of counterfeit brands market scenario and explains how it affects the economy. The goal of this paper is to provide a comprehensive review of counterfeiting of luxury goods, demand and supply side of counterfeiting, various research works carried out in areas of counterfeiting and need for study towards luxury brands counterfeiting in Indian context. KEYWORDS: Counterfeits, Demand and Supply, Global Economy, India, Luxury Brands INTRODUCTION Education Federal authorities seized 1,500 counterfeit Hermes handbags from China at the Port of Los Angeles. The fake handbags, made in China, would have been worth $14 million if sold at full price and were destined for Mexico and the United States (Chang, 2013). Delhi produces 75 per cent of counterfeit goods & caters to clients in markets across city (Vikram, 2013). In Amherst, NY, Homeland security raids kiosks at mall, seizing counterfeit goods. -

Updatedrecognised Awos-05.09.2019

Sl No Code No Name of the AWO Address Place State Tel_No AP002/1964 Peela Ramakrishna Memorial Jeevraksha Guntur 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH 1 Sangham 2 AP003/1971 Animal Welfare Society 27 & 37 Main Road Visakapattinam 530 002 ANDHRA PRADESH 560501 3 AP004/1972 SPCA Kakinada SPCA Complex, Ramanayyapeta, Kakinada 533 003 ANDHRA PRADESH 0884-2375163 AP005/1985 Vety. Hospital Campus, Railway Feeders 4 District Animal Welfare Committee Rd Nellore 524 004 ANDHRA PRADESH 0861-331855 5 AP006/1985 District Animal Welfare Committee Guttur 522 001 ANDHRA PRADESH 6 AP007/1988 Eluru Gosamrakshana Samiti Ramachandra Rao Pet Elluru 534 002 ANDHRA PRADESH 08812-235518 7 AP008/1989 District Animal Welfare Committee Kurnool 518 001 ANDHRA PRADESH AP010/1991 55,Bajana Mandir,Siru Gururajapalam T.R Kandiga PO, Chitoor Dt. 8 Krishna Society for Welfare of Animals Vill. 517571 ANDHRA PRADESH 9 AP013/1996 Shri Gosamrakshana Punyasramam Sattenapalli - 522 403 Guntur Dist. ANDHRA PRADESH 08641-233150 AP016/1998 Visakha Society for Protection and Care of 10 Animals 26-15-200 Main Road Visakapattinam 530 001 ANDHRA PRADESH 0891-2716124 AP017/1998 International Animal & Birds Welfare Teh.Penukonda,Dist.Anantapur 11 Society 2/152 Main Road, Guttur 515 164 ANDHRA PRADESH 08555-284606 12 AP018/1998 P.S.S. Educational Development Society Pamulapadu, Kurnool Dist. Erragudur 518 442 ANDHRA PRADESH 13 AP019/1998 Society for Animal Protection Thadepallikudem ANDHRA PRADESH AP020/1999 Chevela Rd, Via C.B.I.T.R.R.Dist. PO Enkapalli, Hyderabad 500 14 Shri Swaminarayan Gurukul Gaushala Moinabad Mandal 075 ANDHRA PRADESH AP021/1999 Royal Unit for Prevention of Cruelty to 15 Animals Jeevapranganam, Uravakonda-515812 Dist. -

Financial Accessibility of the Street Vendors in India: Cases of Inclusion and Exclusion

FINANCIAL ACCESSIBILITY OF THE STREET VENDORS IN INDIA: CASES OF INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION A study conducted by Sharit K. Bhowmik And Debdulal Saha School of Management and Labour Studies Tata Institute of Social Sciences Mumbai-400 088 for United Nations Development Programme New Delhi September 2011 1 Contents Chapter-1: Introduction Chapter-2: City Information: profile of the respondents and government initiatives Chapter-3: Access to finance: sources, nature and purposes Sources of capital Chapter-4: Role of formal institutions: Insights from data 4.1. Financial Institutions: An Overview 4.2. Role and functions of financial institutions: City-wise scenario 4.2.1. Role of MFIs 4.2.2. Role of SHGs 4.2.3. Role of NGOs Chapter-5: Role of Informal Sources: Realities and Challenges 5.1. Type of money lenders 5.1.1. Daily transaction scheme 5.2. Role of Wholesalers and process of transaction 5.3. High rate of interest and its consequences: 5.4. Survival at the market: street vendors’ perspectives 5.5. Informal sources of capital: Mechanism at the workplace Chapter-6: Recommendations and Conclusion 2 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AAY Antodaya Anna Yojana ACTS Agriculture Consultancy and Technical Services AFSL Arohan Financial Services Limited Ag BDS Agriculture Business Development Services AGM Assistant General Manager AKMI Association of Karnataka Microfinance Institution AMA Ahmedabad Management Association AMC Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation AML Ashmita Microfinance Limited ATIRA Ahmedabad Textile Industries Research Association ATM Automated -

The DILLI HAAT Provides the Ambience of a Traditional Rural Haat Or Village Market, but One Ssuited for More Contemporary Needs

GlobalBuilds Savouring India! The DILLI HAAT provides the ambience of a traditional Rural Haat or village market, but one ssuited for more contemporary needs. Here one sees a synthesis of crafts, food ad cultural activity. DILLI HAAT transports you to the magical world of Indian art and heritage presented through a fascinating panorama of craft, cuisine and cultural activities. The word Haat refers to a weekly market in rural, semi- urban and sometimes even urban India. While the village haat is mobile, flexible arrangement, here it is crafts persons who are mobile. The DILLI HAAT boasts of nearly 200 craft stalls selling native, utilitarian and ethnic products from all over the country. The Food and Craft Bazar is a treasure house of Indian culture, handicrafts and ethnic cuisine. A unique bazaar, in the heart of the city, it displays the richness of Indian culture on a permanent basis. It is a place where one can unwind in the evening and relish a wide variety of cuisine without paying the exhorbitant rates. Step inside the complex for an altogether delightful experience for either buying inimitable ethnic wares, savouring the delicacies of different states or by simply relaxing in the evening with friends and your family. Delhi Haat is the place where you can find the food of most of the Indian States. Come stimulate your appetite in a typical ambience. Savour specialties of different states. The Makki Ki Roti and Sarson Ka Sag of Punjab; Momos from Sikkim; Chowmein from Mizoram; Dal - Bati Choorma from Rajasthan; Shrikhand, Pao-Bhaji and Puram Poli of Maharashtra; Macher Jhol from Bengal; Wazwan, the ceremonial Kashmiri feast; Idli, Dosa and Uttapam of South Indian and Sadya, the traditional feast of Kerala, all are available under one roof. -

Delhi Travel Guide - Wikitravel

Delhi travel guide - Wikitravel http://wikitravel.org/en/Delhi Delhi From Wikitravel Asia : South Asia : India : Plains : Delhi Ads by Google Ginger Delhi Offer Contents 2N/3D Festive Package at INR 4,999! Districts Book Early & Get 15% [+] Understand Off. Hurry. History GingerHotels. com/ Orientation Incl_Breakfast&Tax South Delhi Air India Air Tickets Climate Special Fares @ Suggested reading MakeMyTrip,Starting [+] Get in From Rs. 2400 Only. By plane Book Now & Save By bus MakeMyTrip. com/ [+] By train Special_Fares Delhi Railway Station Singapore Package Delhi Railway Station Book Best Singapore Hazrat Nizamuddin Tour Package at Anand Vihar w/ Us at Rs.57,499. Get [+] Get around Quote Now! By metro Singapore-Tour-Package. By local train Yatra. com [+] By bus Ginger Delhi Offer Hop on Hop off 2N/3D Festive Package By taxi at INR 4,999! By auto rickshaws Book Early & Get 15% By cycle rickshaws Off. Hurry. On foot GingerHotels. com/ Talk Incl_Breakfast&Tax [+] See Red Fort Cheap Flight Humayun's tomb Qutub complex Tickets Museums Book Your Travel in Monuments Advance this Diwali & Parks and gardens Pay Upto 61% less. Religious buildings Hurry! Other www.Cleartrip.Com Do Learn Work [+] Buy Malls Bazaars Handicrafts Clothing Computers Books 1 of 54 21-10-2012 16:39 Delhi travel guide - Wikitravel http://wikitravel.org/en/Delhi [+] Eat Budget Mid-range [+] Splurge Italian Barbeque/grills Japanese Middle Eastern Thai Chinese Korean Afghani Iraqi [+] Drink Coffee / tea Hookah/sheesha Bars/nightclubs Gay and lesbian Delhi [+] Sleep Hotels Near Delhi International Airport [+] Budget Chandni Chowk Paharganj Majnu ka Tilla Other Areas Mid-range Splurge Stay healthy [+] Stay safe Delhi Police [+] Contact Delhi emergency numbers [+] Cope Embassies & High Commissions Get out Delhi is a huge city with several district articles containing sightseeing, restaurant, nightlife and accommodation listings — consider printing them all. -

Jesus and Mary College

Jesus and Mary College (NAAC Accredited ‘A’ Grade) University of Delhi Organizes International Conference On Innovative Approaches for Plastic Free India (IAPFI-2020) 26 February, 2020 Jesus and Mary College Chanakyapuri, New Delhi – 110021. India About the College Jesus and Mary College was founded in July 1968 as a constituent college of the University of Delhi. It is run by the Sisters of Jesus and Mary Congregation founded by St. Claudine Thevenet in France 1818. The motto of the College is THOU ART LIGHT, FILL ME WITH THY LIGHT. The college focuses on the intellectual, cultural, social, and spiritual development of its students to make them compassionate and committed human beings. Today the college caters to more than 2500 students – with 10 Honours Programs and B.A. Restructured with 13 subject combinations. It offers courses at both Under Graduate (UG) and Post Graduate (PG) level in different streams along with a range of short-term courses to empower its female students and to prepare them for vocational and professional life. JMC is also the Centre for Non Collegiate Women Education Board (NCWEB) and Indira Gandhi National Open University (IGNOU). About the International Conference Globally, plastic and its consumption is one of the most significant challenges to life on earth. According to UNEP, around the world, one million plastic drinking bottles are purchased every minute, while up to 5 trillion single-uses plastic bags are used worldwide every year. In total, half of all plastic produced is designed to be used only once — and then thrown away. Plastic waste is now so ubiquitous in the natural environment that it could even mark dominant influence on ecological climate and the beginning of the Anthropocene Era. -

Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat: Futurism and Pirate Modernity in South Asian Electronica

Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat: Futurism and Pirate Modernity in South Asian Electronica Kyle Lindstrom Schirmann A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies Columbia University New York, New York May 1, 2015 © 2015 Kyle Lindstrom Schirmann All rights reserved ABSTRACT Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat: Futurism and Pirate Modernity in South Asian Electronica Kyle Lindstrom Schirmann Ravi Sundaram’s conception of recycled, or pirate, modernity was first deployed to explain the extralegal circuits of production and consumption of pirated and counterfeit goods, particularly in India. This thesis argues that the production, performance, distribution, and consumption of South Asian electronic music can be read under the specter of an aestheticization of the circuits of pirate modernity. Through sampling, glitching, and remixing artifacts, sometimes with pirated software or counterfeit hardware, South Asian electronica situates itself in youth culture as an underground form of sound. This is a music that concerns itself with futurity and futurism, doubly so by its links to the diaspora and to Afrofuturist readings, and with the physicality of the sound wave. The thesis also suggests a shift in the economic and political import of pirate modernity wrought by this aestheticization, examining how it has been appropriated for profit and mobilized for political use. Table of Contents Acknowledgements and Dedication .............................................................................................................. iii Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat: Futurism and Pirate Modernity in South Asian Electronica ............................ 1 Hardware, Greyware, and Pirate Markets ...............................................................................................