Fur Trade Posts in Idaho Publication Date: October 1970

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oregon Historic Trails Report Book (1998)

i ,' o () (\ ô OnBcox HrsroRrc Tnans Rpponr ô o o o. o o o o (--) -,J arJ-- ö o {" , ã. |¡ t I o t o I I r- L L L L L (- Presented by the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council L , May,I998 U (- Compiled by Karen Bassett, Jim Renner, and Joyce White. Copyright @ 1998 Oregon Trails Coordinating Council Salem, Oregon All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Oregon Historic Trails Report Table of Contents Executive summary 1 Project history 3 Introduction to Oregon's Historic Trails 7 Oregon's National Historic Trails 11 Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail I3 Oregon National Historic Trail. 27 Applegate National Historic Trail .41 Nez Perce National Historic Trail .63 Oregon's Historic Trails 75 Klamath Trail, 19th Century 17 Jedediah Smith Route, 1828 81 Nathaniel Wyeth Route, t83211834 99 Benjamin Bonneville Route, 1 833/1 834 .. 115 Ewing Young Route, 1834/1837 .. t29 V/hitman Mission Route, 184l-1847 . .. t4t Upper Columbia River Route, 1841-1851 .. 167 John Fremont Route, 1843 .. 183 Meek Cutoff, 1845 .. 199 Cutoff to the Barlow Road, 1848-1884 217 Free Emigrant Road, 1853 225 Santiam Wagon Road, 1865-1939 233 General recommendations . 241 Product development guidelines 243 Acknowledgements 241 Lewis & Clark OREGON National Historic Trail, 1804-1806 I I t . .....¡.. ,r la RivaÌ ï L (t ¡ ...--."f Pðiräldton r,i " 'f Route description I (_-- tt |". -

Trade and Change on the Columbia Plateau 1750-1840 Columbia Magazine, Winter 1996-97: Vol

Trade and Change on the Columbia Plateau 1750-1840 Columbia Magazine, Winter 1996-97: Vol. 10, No. 4 By Laura Peers Early Europeans saw the Columbia Plateau as a walled fortress, isolated and virtually impossible to penetrate through the Rocky Mountain and Cascade ranges that formed its outer defenses. Fur traders and missionaries saw it as a last frontier, virgin and unspoiled. But this was an outsider's view. To the native people of the region, the Plateau was the center of the world, linked to the four corners of the continent by well-worn paths and a dense social and economic network. In fact, the Plateau was a crossroads for trade, one that became increasingly busy between 1750 and 1850. During this pivotal century, the quickening pace of trade became an uncontrolled torrent, a flash flood of new goods, new ideas and new diseases, an explosion of change, sometimes beneficial and sometimes deadly. By the late prehistoric era there were two major trade centers on the Plateau: at The Dalles, on the middle Columbia River, and at Kettle Falls, several hundred miles away on the upper Columbia. Members of tribes from across the Plateau and from the West Coast to the Missouri River converged on these sites every year. An astonishing quantity and variety of goods were exchanged at these sites, including dried fish from the Columbia; baskets, woven bags and wild hemp for fishnets from the Plateau region; shells, whale and seal oil and bone from the West Coast; pipestone, bison robes and feather headdresses from the Plains; and nuts and roots from as far away as California. -

Historical Conditions

Lower Owyhee Watershed Assessment Lower Owyhee Watershed Assessment IV. Historical Conditions © Owyhee Watershed Council and Scientific Ecological Services Contents A. Pre-contact 6. Oregon Trail roadside conditions B. At contact Owyhee to the Malheur 1. The journals 7. Conclusions 2. The effect of trapping on conditions D. Early settlement 3. General description of the Owyhee 1. Discovery of gold country side 2. Description of the environment 4. Vegetation a. Willows a. Few trees 3. Introduction of resource based b. Willow industries c. Other vegetation a. Livestock industry 5. Fires b. Farming 6. Game c. Salmon a. Lack of big game d. Timber b. Antelope 4. Water c. Deer 5. Roads d. Bison a. Willamette Valley and Cascade e. Native consumption of game Mountain Military Wagon Road 7. Fish 6. Settlements 8. The Owyhee River 7. Effects of livestock 9. River fluctuation 8. Changes and constants 10. Land E. End of the nineteenth century, early twenti- C. Oregon trail travelers eth century 1. General description 1. Mining 2. Climate 2. Grazing Pressure 3. Vegetation 3. Fauna a. Grass and shrubs 4. Fish b. No trees 5. Vegetation 4. Wildlife 6. Geology 5. Fish 7. Settlements IV.1 Lower Owyhee Watershed Assessment Historical Conditions Pre Euro-American contact 8. Farming and the first irrigation along the f. Livestock lower Owyhee River g. Turkeys 9. River functioning h. Moonshine 10. Watson Area i. Watson water use a. People j. Attitude to the dam b. Roads 11. Water use - below dam c. Vegetation 12. Water on the range d. Climate 13. Taylor Grazing Act e. -

Download the Full Report 2007 5.Pdf PDF 1.8 MB

The Northwest Power and Conservation Council’s Directory of Columbia River Basin Tribes Council Document Number: 2007-05 Table of Contents I. Introduction 1 II. Tribes and Tribal Confederations 5 The Burns Paiute Tribe 7 The Coeur d’Alene Tribe 9 The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation 12 The Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation 15 The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation 18 The Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon 21 The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation 23 The Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation of Oregon 25 The Kalispel Tribe of Indians 28 The Kootenai Tribe of Idaho 31 The Nez Perce Tribe 34 The Shoshone Bannock Tribes of the Fort Hall Reservation 37 The Shoshone-Paiute Tribes of the Duck Valley Reservation 40 The Spokane Tribe of Indians 42 III. Canadian First Nations 45 Canadian Columbia River Tribes (First Nations) 46 IV. Tribal Associations 51 Canadian Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fisheries Commission 52 Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission 53 Upper Columbia United Tribes 55 Upper Snake River Tribes 56 The Northwest Power and Conservation Council’s Tribal Directory i ii The Northwest Power and Conservation Council’s Tribal Directory Introduction The Northwest Power and Conservation Council’s Tribal Directory 1 2 The Northwest Power and Conservation Council’s Tribal Directory Introduction The Council assembled this directory to enhance our understanding and appreciation of the Columbia River Basin tribes, including the First Nations in the Canadian portion of the basin. The directory provides brief descriptions and histories of the tribes and tribal confedera- tions, contact information, and information about tribal fi sh and wildlife projects funded through the Council’s program. -

Payette Rad!O Limited 730 St

OREGON STATE UN VERS TV LIBRARIES III 11111111111 liiiI I 11111111 12 0143739858 Printed Privately for PAYETTE RAD!O LIMITED 730 ST. JAMES sr.W., MONTREAL 3,c. 1961 THE OREGON COUNTRY UNDER THE UNION JACK A REFERENCE BOOK OF HISTORICAL DOCUMENTS FOR SCHOLARS AND HISTORIANS B. C. PAYETTE Printed privately for PAYETTE RADIO LIMITED 730 St James Street W Montreal 3, Canada 1961 THE SOURCE OF DOCUMENTS THE HUDSON'S BAY COMPANY THE PUBLIC ARCHIVES OF CANADA. THE MONTREAL MUNICIPAL LIBRARY. THE FAYETTE PAPERS. TO: Pierre Brunet, Assistant Archivist, The Public Archives of Canada Miss Marie Baboyant, Librarian, The Montreal Municipal Library Dr. Roger C. Fitch, Fayette, Idaho "He wanted to know" Hervé Jolicoeur, Montreal. "He did all the work" Miss Agnes Kemp HoInes "For her help" David A. Murphy "For his assistance" B. C. PAYETTE Montreal 1961 THE OREGON COUNTRY under THE STARS AND STRIPES The Oregon Country was made up of what is now the States of Oregon, Washington, Idaho and we stern parts of Wyoming and Montana. In 1811 the Oregon Country was occupied by the Pacific Fur Company, an American Company with headquarters in Montreal. John Jacob Astor was the owner and the members of this company were called Astorians. The Astorians traded and trapped from the 43rd to the 48th parallel from 1811 to 1813 THE OREGON COUNTRY AND THE WAR OF 181Z The documentations in this book start from this period B. C. FAYETTE Montreal - 1961 THIS BOOK HAS NOT BEEN EDITED. ONLY A MINIMUM OF NOTES HAVE BEEN ADDED. Rather important page s: - Page13 THE UNION JACK Page 175 THE RESTORATION Page 185 THE MONROE DOCTRINE (FROM THE PUBLIC ARCHIVES OF CANADA) EXTRACT FROM MR. -

The Sacagawea Mystique: Her Age, Name, Role and Final Destiny Columbia Magazine, Fall 1999: Vol

History Commentary - The Sacagawea Mystique: Her Age, Name, Role and Final Destiny Columbia Magazine, Fall 1999: Vol. 13, No. 3 By Irving W. Anderson EDITOR'S NOTE The United States Mint has announced the design for a new dollar coin bearing a conceptual likeness of Sacagawea on the front and the American eagle on the back. It will replace and be about the same size as the current Susan B. Anthony dollar but will be colored gold and have an edge distinct from the quarter. Irving W. Anderson has provided this biographical essay on Sacagawea, the Shoshoni Indian woman member of the Lewis and Clark expedition, as background information prefacing the issuance of the new dollar. THE RECORD OF the 1804-06 "Corps of Volunteers on an Expedition of North Western Discovery" (the title Lewis and Clark used) is our nation's "living history" legacy of documented exploration across our fledgling republic's pristine western frontier. It is a story written in inspired spelling and with an urgent sense of purpose by ordinary people who accomplished extraordinary deeds. Unfortunately, much 20th-century secondary literature has created lasting though inaccurate versions of expedition events and the roles of its members. Among the most divergent of these are contributions to the exploring enterprise made by its Shoshoni Indian woman member, Sacagawea, and her destiny afterward. The intent of this text is to correct America's popular but erroneous public image of Sacagawea by relating excerpts of her actual life story as recorded in the writings of her contemporaries, people who actually knew her, two centuries ago. -

Road to Oregon Written by Dr

The Road to Oregon Written by Dr. Jim Tompkins, a prominent local historian and the descendant of Oregon Trail immigrants, The Road to Oregon is a good primer on the history of the Oregon Trail. Unit I. The Pioneers: 1800-1840 Who Explored the Oregon Trail? The emigrants of the 1840s were not the first to travel the Oregon Trail. The colorful history of our country makes heroes out of the explorers, mountain men, soldiers, and scientists who opened up the West. In 1540 the Spanish explorer Coronado ventured as far north as present-day Kansas, but the inland routes across the plains remained the sole domain of Native Americans until 1804, when Lewis and Clark skirted the edges on their epic journey of discovery to the Pacific Northwest and Zeb Pike explored the "Great American Desert," as the Great Plains were then known. The Lewis and Clark Expedition had a direct influence on the economy of the West even before the explorers had returned to St. Louis. Private John Colter left the expedition on the way home in 1806 to take up the fur trade business. For the next 20 years the likes of Manuel Lisa, Auguste and Pierre Choteau, William Ashley, James Bridger, Kit Carson, Tom Fitzgerald, and William Sublette roamed the West. These part romantic adventurers, part self-made entrepreneurs, part hermits were called mountain men. By 1829, Jedediah Smith knew more about the West than any other person alive. The Americans became involved in the fur trade in 1810 when John Jacob Astor, at the insistence of his friend Thomas Jefferson, founded the Pacific Fur Company in New York. -

Cannon Streetcar Suburb District Nomination

DRAFT 07-21-2020 Spokane Register of Historic Places Nomination Spokane City/County Historic Preservation Office, City Hall, Third Floor 808 Spokane Falls Boulevard, Spokane, Washington 99201-3337 1. Name of Property Historic Name: Cannon’s Addition And/Or Common Name: Cannon Streetcar Suburb Historic District 2. Location Street & Number: Various City, State, Zip Code: Spokane, WA 99204 Parcel Number: Various 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use ☐building ☐public ☒both ☒occupied ☐agricultural ☐museum ☐site ☐private ☐work in progress ☒commercial ☐park ☐structure ☐educational ☒residential ☐object Public Acquisition Accessible ☐entertainment ☐religious ☒district ☐in process ☐yes, restricted ☐government ☐scientific ☐being considered ☒yes, unrestricted ☐industrial ☐transportation ☐no ☐military ☒other 4. Owner of Property Name: Various Street & Number: n/a City, State, Zip Code: n/a Telephone Number/E-mail: n/a 5. Location of Legal Description Courthouse, Registry of Deeds Spokane County Courthouse Street Number: 1116 West Broadway City, State, Zip Code: Spokane, WA 99260 County: Spokane 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Title: Ninth Avenue National Register Historic District Date: Enter survey date if applicable ☒Federal ☐State ☐County ☐Local Depository for Survey Records: Spokane Historic Preservation Office 7. Description Architectural Classification Condition Check One ☐excellent ☐unaltered ☒good ☒altered ☐fair ☐deteriorated Check One ☐ruins ☒original site ☐unexposed ☐moved & date ______________ Narrative statement of description is found on one or more continuation sheets. 8. Spokane Register Categories and Statement of Significance Applicable Spokane Register of Historic Places category: Mark “x” on one or more for the categories that qualify the property for the Spokane Register listing: ☒A Property is associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of Spokane history. -

Idaho: Lewis Clark Byway Guide.Pdf

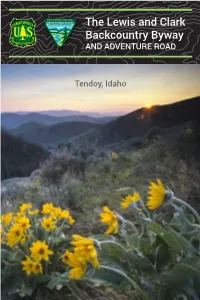

The Lewis and Clark Backcountry Byway AND ADVENTURE ROAD Tendoy, Idaho Meriwether Lewis’s journal entry on August 18, 1805 —American Philosophical Society The Lewis and Clark Back Country Byway AND ADVENTURE ROAD Tendoy, Idaho The Lewis and Clark Back Country Byway and Adventure Road is a 36 mile loop drive through a beautiful and historic landscape on the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail and the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail. The mountains, evergreen forests, high desert canyons, and grassy foothills look much the same today as when the Lewis and Clark Expedition passed through in 1805. THE PUBLIC LANDS CENTER Salmon-Challis National Forest and BLM Salmon Field Office 1206 S. Challis Street / Salmon, ID 83467 / (208)756-5400 BLM/ID/GI-15/006+1220 Getting There The portal to the Byway is Tendoy, Idaho, which is nineteen miles south of Salmon on Idaho Highway 28. From Montana, exit from I-15 at Clark Canyon Reservoir south of Dillon onto Montana Highway 324. Drive west past Grant to an intersection at the Shoshone Ridge Overlook. If you’re pulling a trailer or driving an RV with a passenger vehicle in tow, it would be a good idea to leave your trailer or RV at the overlook, which has plenty of parking, a vault toilet, and interpretive signs. Travel road 3909 west 12 miles to Lemhi Pass. Please respect private property along the road and obey posted speed signs. Salmon, Idaho, and Dillon, Montana, are full- service communities. Limited services are available in Tendoy, Lemhi, and Leadore, Idaho and Grant, Montana. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

NPS Form 10-900 (7-81) United States Department off the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections____^________ 1. Name historic Ross Fork Oregon Short Line Railroad Depot and/or common Fort Hall Oregon Short Line Railroad Depot 2. Location street & number Agency RgjjTd. dT4S R34E, Section 36, ST&; city, town Fort Hall H/A vicinity of state Idaho code 016 code Oil 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district X public occupied agriculture museum x building(s) private X unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object N/A in process yes: restricted government scientific N/A being considered X yes: unrestricted industrial transportation __ no military — X. other: vacant 4. Owner of Property name Shoshone/Bannock Tribes street & number N/A city, town Fort Hall N/A vicinity of state Idaho 83203 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Bingham County Courthouse street & number city, town Blackfoot state Idaho 6. Representation in Existing Surveys________ title Idaho State Historic Sites Inventory has this property been determined eligible? __ yes _X_ no date 1982 __federal X state __county __local city, town Boise state I daho 7. Description Condition Check one Check one __ excellent X deteriorated __ unaltered __ original site __ good __ ruins x altered J£_ moved date 1968______________ __ fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Ross Fork Oregon Short Line Railroad Depot is a one-and-one-half-story frame building of wood-stud construction with shiplap siding painted white and yellow. -

Environmental Degradation, Resource War, Irrigation and the Transformation of Culture on Idaho's Snake River Plain, 1805--1927

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 12-2011 Newe country: Environmental degradation, resource war, irrigation and the transformation of culture on Idaho's Snake River plain, 1805--1927 Sterling Ross Johnson University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Military History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Johnson, Sterling Ross, "Newe country: Environmental degradation, resource war, irrigation and the transformation of culture on Idaho's Snake River plain, 1805--1927" (2011). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 1294. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/2838925 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEWE COUNTRY: ENVIRONMENTAL DEGRADATION, RESOURCE WAR, IRRIGATION AND THE TRANSFORMATION -

CTUIR Traditional Use Study of Willamette Falls and Lower

Traditional Use Study of Willamette Falls and the Lower Columbia River by the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation Jennifer Karson Engum, Ph.D. Cultural Resources Protection Program Report prepared for CTUIR Board of Trustees Fish and Wildlife Commission Cultural Resources Committee CAYUSE, UMATILLAANDWALLA WALLA TRIBES November 16, 2020 CONFEDERATED TRIBES of the Umatilla Indian Reservation 46411 Timíne Way PENDLETON, OREGON TREATY JUNE 9, 1855 REDACTED FOR PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION Traditional Use Study of Willamette Falls and the Lower Columbia River by the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation Prepared by Jennifer Karson Engum, Ph.D. Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation Department of Natural Resources Cultural Resources Protection Program 46411 Timíne Way Pendleton, Oregon 97801 Prepared for CTUIR Board of Trustees Fish and Wildlife Commission Cultural Resources Committee November 16, 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Umatilla (Imatalamłáma), Cayuse (Weyíiletpu), and Walla Walla (Walúulapam) peoples, who comprise the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR), have traveled throughout the west, including to the lower Columbia and Willamette Rivers and to Willamette Falls, to exercise their reserved treaty rights to hunt, fish, and gather the traditional subsistence resources known as the First Foods. They have been doing so since time immemorial, an important indigenous concept which describes a time continuum that spans from ancient times to present day. In post- contact years, interactions expanded to include explorers, traders and missionaries, who brought with them new opportunities for trade and intermarriage as well as the devastating circumstances brought by disease, warfare, and the reservation era. Through cultural adaptation and uninterrupted treaty rights, the CTUIR never ceased to continue to travel to the lower Columbia and Willamette River and falls for seasonal traditional practice and for other purposes.